Business Lending

Why Small Businesses Sought Financing in 2017, and Why They Were Denied

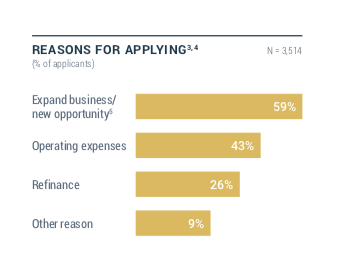

May 24, 2018 Nearly 60 percent of small businesses applied for financing in 2017 because they wanted to expand their business or pursue new opportunities, according to the latest report by the Federal Reserve. Forty-three percent of small businesses sought financing for operating expenses while 26 percent sought capital for refinancing. Nine percent had a different reason.

Nearly 60 percent of small businesses applied for financing in 2017 because they wanted to expand their business or pursue new opportunities, according to the latest report by the Federal Reserve. Forty-three percent of small businesses sought financing for operating expenses while 26 percent sought capital for refinancing. Nine percent had a different reason.

Of course, not all applications are funded. Forty-six percent of small businesses received all the financing they sought, 12 percent received most (more than 50 percent) of it, 20 percent received some (less than 50 percent) of the financing they desired and 23 percent were denied financing altogether.

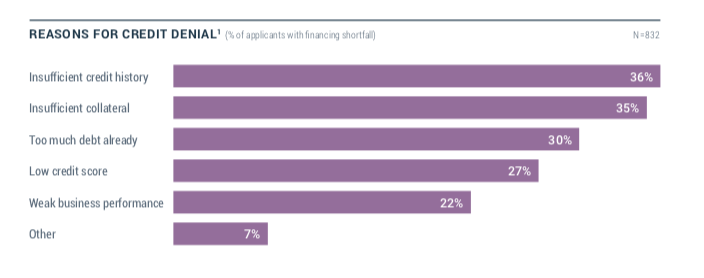

Of the reasons why merchants were denied funding, “Having insufficient credit history” ranked number one, according to the report. A very close second was “Having insufficient collateral,” followed by “Having too much debt already.” After that, in descending order, came “Low credit score,” “Weak business performance” and “Other.”

The “Having insufficient collateral” category does not apply for MCA financing, but the other categories do. According to Nick Gregory, founding partner at Central Diligence Group, which provides MCA underwriting services, “Having too much debt already” is perhaps the main reason why merchants seeking cash advances get declined.

“A lot of times the merchants are overleveraged,” Gregory said.

He explained that if a merchant also has something like two MCA arrangements (or positions) already, that merchant likely has taken on too many contractual obligations which will often be a reason to decline the application. In Gregory’s experience, another common reason for declining an MCA financing application is “Weak business performance.”

Contradictory to the Federal Reserve report’s top reason for denying financing to a small business borrower, Gregory said that “Having insufficient credit history” is seldom a reason to deny MCA financing. This disconnect likely comes from the fact that the report includes all types of small business financing, with MCA accounting for just seven percent. The number maybe seem small, but it continues to increase while small business applications for factoring have decreased.

More Small Businesses Seeking Merchant Cash Advances Than Factoring

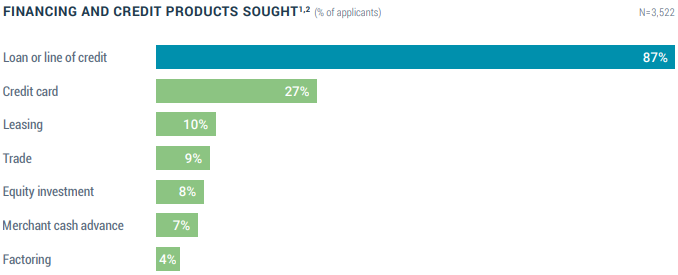

May 23, 2018 Seven percent of small employer firms in the US that applied for financing in 2017 applied for a merchant cash advance, the latest report by the Federal Reserve shows, while only 4% applied for factoring. Small employer owned firms were defined as businesses that have 1 to 499 full-or part-time employees. 69% of those surveyed generated less than $1 million in revenue last year. That revenue demographic may be on the low end for the factoring industry though. Factoring’s popularity in that demographic, however, decreased in 2017, according to the report. The 4% figure of small businesses that applied for factoring in 2017 was down from 7% in 2016.

Seven percent of small employer firms in the US that applied for financing in 2017 applied for a merchant cash advance, the latest report by the Federal Reserve shows, while only 4% applied for factoring. Small employer owned firms were defined as businesses that have 1 to 499 full-or part-time employees. 69% of those surveyed generated less than $1 million in revenue last year. That revenue demographic may be on the low end for the factoring industry though. Factoring’s popularity in that demographic, however, decreased in 2017, according to the report. The 4% figure of small businesses that applied for factoring in 2017 was down from 7% in 2016.

Auto and equipment loans had the highest approval rates among all financing options available to small businesses, at 82%. Merchant cash advances followed behind them at 79%. Lines of credit and business loans carried approval rates of 69% and 62% respectively. SBA loans came in at 54%.

When it comes to satisfaction, online lenders such as Lending Club, OnDeck, CAN Capital, and PayPal, have markedly improved over time, the report shows. The net satisfaction score of online lenders has increased from 19% in 2015 to 35% in 2017.

On transparency, online lenders rank at about the same level as large banks, though applicants were more likely to be dissatisfied with the interest rates of an online lender and the long and difficult application process with a large bank.

StreetShares to Change Fee Policy

May 22, 2018StreetShares sent out an email on Monday saying that they will no longer automatically deduct origination fees from their loans to small businesses. Instead, according to the email, merchants will receive their full amount and it will be up to the merchant to decide whether they would like to pay off the origination fee immediately or include it in their weekly payment.

Kabbage Reveals Plans for a ‘Reverse Play’

May 22, 2018 When it comes to lending, the business models of Square and PayPal may be too good to ignore.

When it comes to lending, the business models of Square and PayPal may be too good to ignore.

According to Reuters, Kabbage plans to launch its own payment processing service by year-end. “The monoline businesses have a hard time succeeding long term,” Kabbage co-founder Kathryn Petralia is quoted as saying.

While Square and PayPal started off in payments and added lending, Kabbage sees the value proposition of the reverse play, to start off in lending and add payments.

But another Square and PayPal rival may not. Back in October, deBanked questioned OnDeck CEO Noah Breslow during an interview about this very thing. At the time, Breslow responded that they were not going to sell merchant processing. “Never say never,” he said, “but not in the near future.”

Square and PayPal’s lending businesses differ from other online lenders in that they can solicit their existing payments customer base at virtually no cost. OnDeck, meanwhile, spent $53 million last year alone on sales and marketing to acquire loan customers.

Square’s acquisition of payments customers is not cheap, however. The company spent $253 million in sales and marketing last year. The advantage is in not needing to shell out additional cost to convert them into loan customers.

OnDeck still held the lead over both Kabbage and Square last year in loan originations at $2.1B vs $1.5B and $1.17B respectively. PayPal was not ranked.

Missed Broker Fair? Get the Kit and Presentations

May 21, 2018

If you missed Broker Fair, you can still get your hands on some of the gear and the presentations. Simply email info@brokerfair.org and ask to be shipped a copy of the Broker Fair Kit. The accessories, which will only be provided while supplies last, include a USB drive with the day’s presentations, a Broker Fair bag, a Broker Fair shirt, a deBanked magazine, a Broker Fair handbook, and more.

Also, don’t wait too late to REGISTER for deBanked’s half-day event in San Diego on October 4th. deBanked Connect: San Diego will connect funders, brokers, and folks from the industry for networking and cocktails!

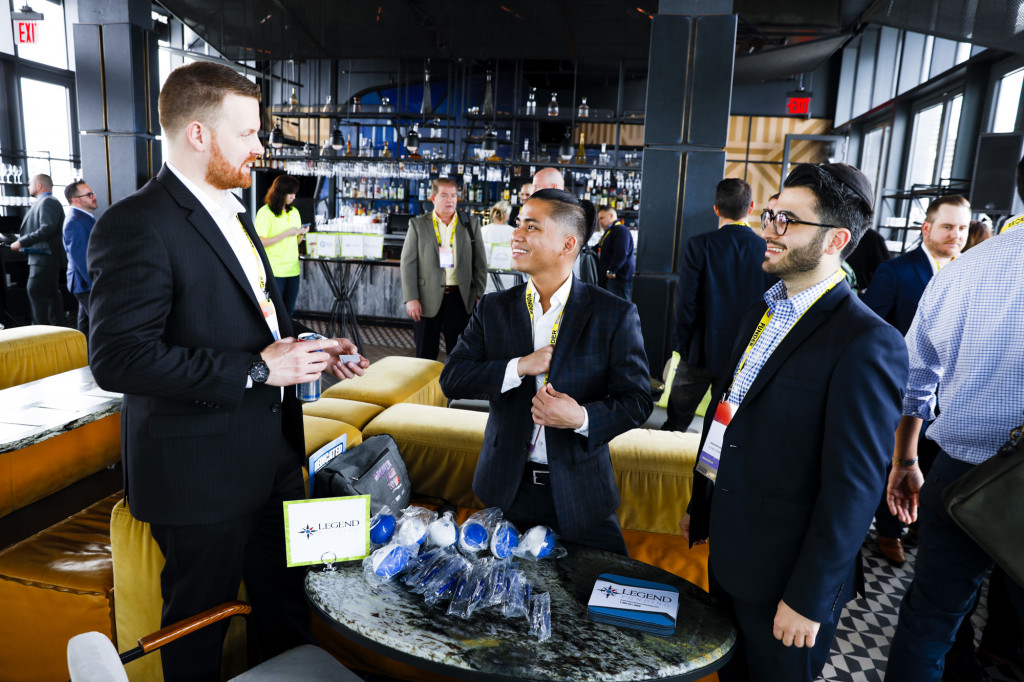

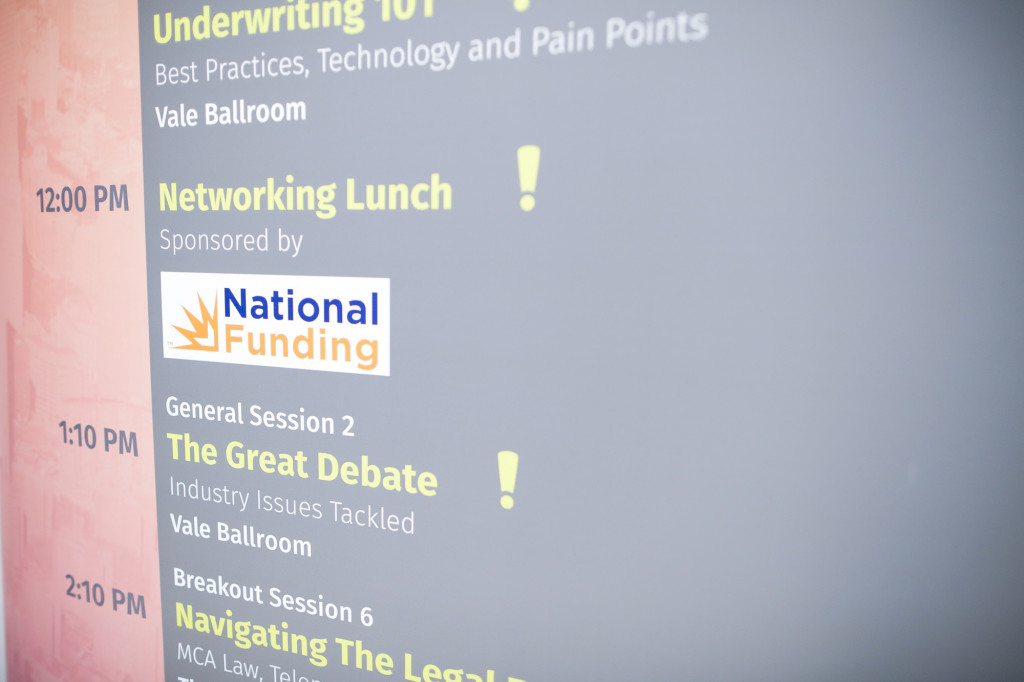

Broker Fair 2018 Story Continued

May 18, 2018A continuation of Broker Fair 2018 through photos:

We’ll publish the entire cache of them in the coming weeks.

JOIN US OCTOBER 4TH IN SAN DIEGO AT THE ANDAZ FOR A SPECIAL HALF-DAY INDUSTRY NETWORKING EVENT

Couldn’t find yourself in any of our photos? We’ll publish the full album in the following weeks.

The Broker Fair 2018 Story Through Photos

May 18, 2018Broker Fair 2018 was an amazing day of inspiration, education, and opportunities. We’ve posted some of our photo footage below:

JOIN US OCTOBER 4TH IN SAN DIEGO AT THE ANDAZ FOR A SPECIAL HALF-DAY INDUSTRY NETWORKING EVENT

Couldn’t find yourself in any of our photos? We’ll publish the full album in the following weeks.

Fundbox Partners with Eventbrite to Provide Credit to Event Organizers

May 17, 2018 Today Fundbox announced an integration with Eventbrite that will give small business event creators access to capital.

Today Fundbox announced an integration with Eventbrite that will give small business event creators access to capital.

Fundbox Chief Business Officer Sebastian Rymarz told deBanked that event planners for small businesses often have to lay out a lot of money up front – to secure a venue, rent equipment or pay for a performer – before they get paid through ticket sales later.

“There’s this mis-timing between expenses and revenue,” Rymarz said. “There’s an acute need and we’re able to serve [event creators] by providing them with capital to fund those events.”

Funding a company as it anticipates future earnings sounds akin to factoring. But this solution for event creators is not a factoring product. In fact, Rymarz said that Fundbox does not have a factoring product. Instead, this new solution is a new application of what the company calls its Fundbox Line product. This is a line of credit that is paid back weekly over 12 to 24 weeks, regardless of when an invoice is paid, or when tickets are sold.

Fundbox doesn’t purchase invoices. It doesn’t even verify if an invoice exists. Instead, the company relies on its technology. Once an application is submitted, its proprietary system reveals a company’s payment history, its clients, vendors and other information that paints a picture of its creditworthiness. The data system, which Rymarz calls a “ledger graph,” is a web of thousands of small and medium-sized businesses that contains information about the businesses’ relationships to one another.

“Every customer that applies makes our algorithms smarter,” Rymarz said.

He also explained that Fundbox does not employ a single underwriter. Rather, the company invests heavily in developing technology, like its ledger graph. Rymarz said that of the company’s roughly 170 employees, 60 percent of them are either machine learning experts, data scientists or engineers.

The company, co-founded in 2013 by CEO Eyal Shinar, is headquartered in San Francisco and has a research and development team in Tel Aviv.