Why Square Ditched Their Merchant Cash Advance Program

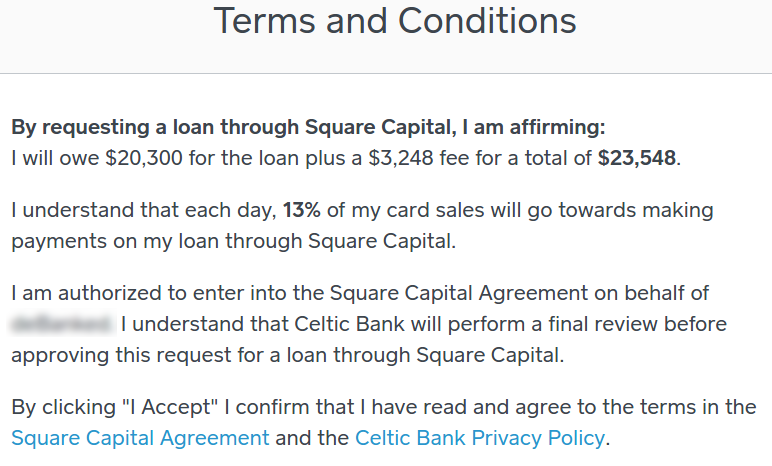

March 27, 2016 Square did $400 million in merchant cash advances last year. Now they are no longer even offering them. To fill the void, they’ve partnered up with Celtic Bank to issue a unique kind of merchant loan, one in which borrowers have a fixed term to repay but make their payments daily by diverting a percentage of every transaction they process to Square.

Square did $400 million in merchant cash advances last year. Now they are no longer even offering them. To fill the void, they’ve partnered up with Celtic Bank to issue a unique kind of merchant loan, one in which borrowers have a fixed term to repay but make their payments daily by diverting a percentage of every transaction they process to Square.

But why make this change? After all, Square reported that its merchant cash advances typically tended to cycle through to completion in approximately nine months despite there being no fixed term. Their loans will have terms of 18 months, almost ensuring that money will turn over slower, not faster.

Todd Baker, the managing principal of Broadmoor Consulting LLC, says it’s a P/E play. That’s because as part of the change, Square will not be keeping the bulk of the loans on their balance sheet. Instead, they’ll be bundled together and sold to institutional investors. That positions them to be an originator or marketplace dependent on fee income instead of a lender. “Banks and lenders trade at 12x-15x p/e while tech trades at infinity,” Baker said.

Square likely encountered trouble trying to bundle up merchant cash advances because their legal standing across states is not as defined. Celtic Bank-issued-loans however are considered to be rather protected under federal preemption laws established under the Federal Deposit Insurance Act.

But that’s not the whole story either

Online lenders were widely criticized in the wake of the San Bernardino attacks after it was learned the terrorists obtained a loan from Prosper. “The issue may end up being whether marketplace lenders are too easy of a source of cash to finance terrorist attacks,” said Guggenheim Partners analyst Jaret Seiberg in a research letter back in December.

Square’s merchant cash advance program had very little underwriting. The focus was almost entirely on a merchant’s historical sales activity. No credit check was required, nor did applicants have to supply a photo ID or financial statements. This one-click process may have played a major role in originating $400 million in merchant cash advances in 2015, but it probably raised red flags with regulators.

Notably, the new Square Capital application page makes light of this issue. “To help the government fight the funding of terrorism and money laundering activities, Federal law requires all financial institutions to obtain verify and record information that identifies each person who opens an account,” it says. “What this means for you: When you open an account, we will ask for your name, address, date of birth, and other information that will allow us to identify you. We may also ask to see your driver’s license and other identifying documents.”

There’s easy and then there’s too easy. For Square, $400 million a year in merchant cash advances may have been proof of concept for demand but also proof that it was time to slow it down just one notch and make sure they aren’t being reckless.

Few would be impressed by one-click no-underwriting funding if it meant money flowed into the coffers of terrorists even once. Similarly, institutional investors would not be too happy if it was deemed that all of the California merchant cash advances in a bundle they bought were subject to a class action lawsuit. Square can now focus on what they are known for, technology, and perhaps improve their market cap.

By moving away from merchant cash advances, Square has killed at least three birds with one stone. Long live the bank charter model.

Square Swaps Out Merchant Cash Advances for Business Loans

March 25, 2016 Square’s merchant cash advance program is already among the biggest in the world, but they’ve got even bigger plans, or maybe just different ones.

Square’s merchant cash advance program is already among the biggest in the world, but they’ve got even bigger plans, or maybe just different ones.

The company announced on Thursday that they will now be offering true business loans as well through a partnership with Celtic Bank, an industrial bank chartered by the State of Utah. The WSJ reports that loan payments will also be made via a split of future credit card sale activity but with the caveat of there ultimately being a fixed term. This is coincidentally how PayPal’s loan product works.

The WSJ makes it seem as if both products will run alongside each other, but a Square merchant revealed to deBanked that all of the language on Square Capital’s application portal has changed from advances to loans. Even the promotional materials have changed to reflect that it may take more than just an automated review of historical credit card sales activity to get approved and funded. Also, all Square loans are subject to credit approval, whereas no credit check was required for merchant cash advances. Applicants may be required to produce a photo ID and other documents for further verification. North Dakota businesses are prohibited from borrowing altogether.

Square’s loans require that merchants process at least $10,000 or more a year. Borrowers must pay at least 1/18th of their initial loan balance every 60 days. PayPal by comparison requires that their borrowers pay down 10% of their loan amount every 90 days.

A Square merchant was not able to locate any mention of the merchant cash advance program. It’s all loans now.

Did Square really just add business loans to their arsenal or have they traded MCAs for the bank charter lending model?

Update: 3/25 2:54 PM Square confirmed that they have indeed replaced their merchant cash advance program with the loan program.

Our Square Capital program is transitioning from merchant cash advances to flexible loans. https://t.co/oUyRtNgVSS pic.twitter.com/ELXC7ayJyU

— Square (@Square) March 25, 2016

Bizfi Partners With West Coast Banking Group

March 17, 2016Bizfi will be the exclusive alternative finance solutions provider for small businesses that are members of the Western Independent Bankers, a trade association of community banks in the west coast.

Small businesses in the midwest and west coast in states including Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming can benefit from this partnership. Bizfi’s marketplace partners with lenders like OnDeck, Funding Circle and Kabbage.

“WIB member banks are the leading funders of America’s small businesses,” said Michael Delucchi, President and Chief Executive Officer of WIB and WIB Service Corporation. “With Bizfi as a WIB Premier Solutions Provider we are able to offer their expertise in alternative financing and superior technology to our member banks and deliver a complete solution for small business funding.”

Earlier this month, Bizfi partnered with The New York State Restaurant Association to provide business financing for its 2,000 small businesses in the restaurant space.

Merchant Cash Advances Not Governed by Truth in Lending Act, Fed Says

March 16, 2016 Ellyn Terry, an Economic Policy Analysis Specialist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, wrote on the Fed’s blog that merchant cash advances are not governed by the Truth in Lending Act.

Ellyn Terry, an Economic Policy Analysis Specialist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, wrote on the Fed’s blog that merchant cash advances are not governed by the Truth in Lending Act.

“Because an MCA is structured as a commercial transaction instead of a loan, it is regulated by the Uniform Commercial Code in each state instead of by banking laws such as the Truth in Lending Act,” wrote Fed analyst Ellyn Terry on March 15th. “Consequently, the provider does not have to follow all of the regulations and documentation requirements (such as displaying an APR) associated with making loans.”

While Terry applies some incorrect characteristics to describe the nature of the parties in a future receivable purchase transaction (by calling them a lender and borrower instead of a buyer and seller), she was able to broadly describe the nature of MCAs.

“MCAs have been around for decades, but their popularity has risen in the wake of the financial crisis,” she wrote. “Typically a lump-sum payment in exchange for a portion of future credit card sales, the terms of MCAs can be enticing because repayment seems easier than paying off a structured business loan that requires a fixed monthly payment.”

Commercial Finance Coalition Emerges – An All Inclusive MCA Industry Trade Group

March 16, 2016 A new trade association hopes to bring together every type of company in the alternative-finance industry to form a united front capable of managing state and federal regulation.

A new trade association hopes to bring together every type of company in the alternative-finance industry to form a united front capable of managing state and federal regulation.

The fledgling Commercial Finance Coalition (CFC) welcomes potential members that include funders, brokers, payments processors, data providers and collection agencies, said Matt Patterson, CEO of Sioux Falls, SD-based Expansion Capital Group LLC and a board member and organizer of the new trade group.

Patterson began thinking about forming an association early last year when he learned that the established Small Business Finance Association (SBFA), formerly the North American Merchant Advance Association, wasn’t communicating with legislators and regulators on behalf of the industry. “When I talked to them six or nine months ago, they had no road map for affecting legislation or regulation,” he said.

Since then, the SBFA has hired an executive director with legislative and association experience to tell the industry’s story on Capitol Hill. (See here.) So, two industry groups now plan to begin contacting government officials to educate them on the cause of small-business alternative finance.

The decision to create the CFC came at a dinner meeting convened Dec. 3 in New York. That gathering came together after several months of conference calls and videoconferences, Patterson said.

The CFC is working with two well-established lobbying groups, Patterson noted. Both organizations advised the CFC during its formation, he said.

The CFC is working with two well-established lobbying groups, Patterson noted. Both organizations advised the CFC during its formation, he said.

Law firm WilmerHale was selected to represent the CFC. The combination of Polaris and WilmerHale will give the association an immediate Washington presence, he noted.

The group intends to write best practices for its members but doesn’t contemplate starting a trade show, trade publication or merchant watch list, Patterson said.

The CFC is beginning its journey with nearly 20 member companies, according to Patterson. Recruitment of additional members is scheduled to intensify after the association has been operating for a while.

Inviting members from all facets of the industry indicates a philosophy that differs from that of the SBFA, which includes only funders on its roster, Patterson said. “We want to be inclusive,” he said. “We’re interested in building a broad base of constituents that all have an incentive to see that the industry survives and thrives.”

The coalition’s trusted service providers include:

- Arena Strategies

- Catalyst Group

- Polaris Consulting

- Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr

“Me, Too” Lenders Something to Worry About, Says Former OnDeck Investor

March 11, 2016 Lending Club, SoFi and OnDeck will endure, wrote Matt Harris, a former OnDeck board member and investor, and current Managing Director for Bain Capital Ventures. In a blog post that approached 4,000 words, Harris admits that he has not invested in a single lender since OnDeck.

Lending Club, SoFi and OnDeck will endure, wrote Matt Harris, a former OnDeck board member and investor, and current Managing Director for Bain Capital Ventures. In a blog post that approached 4,000 words, Harris admits that he has not invested in a single lender since OnDeck.

“It is still possible, though I believe increasingly unlikely, that marketplace lending will be a durable innovation,” he wrote. He bases that on the assumption that origination platforms with no skin in the game are not sustainable over the long term and that what really made companies like Lending Club special is that it has “scale, a brand in the capital markets for producing high quality assets, and an unbelievable management team.”

All of the other perceived advantages don’t make sense, he argues. The average cost of funds for a bank “is 0.06%, assuming they fund their loans using deposits. OnDeck’s funding costs for its assets averages 5.3%. Lending Club has paid a median return to its asset purchasers of 7.4%.” Banks have lower operating costs as well. “I’ll point out that most of the bank expenses they highlight are fixed expenses like branches and compliance, which makes that expense burden irrelevant to the profitability of the marginal loan,” he wrote.

Even on technology, Harris says banks spend less, and on big data credit scoring, he says a lot of the factors marketplace lenders might find useful in predicting performance cannot be used legally because they end up correlating with a protected class such as race, whether it’s directly or indirectly.

“Things are going to get harder before they get easier,” Harris wrote, though he thinks companies like OnDeck and Lending Club are positioned to last. Everyone else who copied their model is in shaky territory. And yet through it all, he is optimistic. “For the first time in a decade, I’m feeling like it’s a great time to be starting a lending company,” he said.

Square’s Merchant Cash Advance Program Now Among Biggest in the World

March 10, 2016Square originated more than $400 million worth of merchant cash advances advances in 2015, according to their Q4 earnings report. Their average deal size was just shy of $6,000. The result is a 300% increase year-over-year and makes them one of the largest players in that industry worldwide.

RANKINGS

| Company Name | 2015 Funding Volume | 2014 Funding Volume |

| OnDeck | $1,900,000,000 | $1,200,000,000 |

| CAN Capital | $1,500,000,000 | $1,000,000,000 |

| Funding Circle | $1,200,000,000 | $600,000,000 |

| PayPal Working Capital | $900,000,000 | $250,000,000 |

| Bizfi | $480,000,000 | $277,000,000 |

| Fundry (Yellowstone Capital) | $422,000,000 | $290,000,000 |

| Square Capital | $400,000,000 | $100,000,000 |

| Strategic Funding Source | $375,000,000 | $280,000,000 |

A much longer list will be available in deBanked’s March/April 2016 Magazine Issue. SUBSCRIBE FREE to make sure you obtain a copy.

MFS Global Co-founder Launches Own Brokerage

March 9, 2016 Co-founder and COO of MFS Global, Robert Abramov launched his own ISO brokerage called Flow Rich Capital and departed from his role at MFS.

Co-founder and COO of MFS Global, Robert Abramov launched his own ISO brokerage called Flow Rich Capital and departed from his role at MFS.

The new company based in Las Vegas has already signed on partners like CAN Capital. Abramov wants to keep the business small and minimal, with not more than five lenders. While he will exit from MFS Global’s day-to-day business, he will continue to hold equity and be part-owner in the company.

“He is pretty much transitioned out but he is still an active member of the executive staff,” said Tom Abramov, founder and CEO of MFS Global. “I am sure he is going to knock it out of the park and I hope he sends us deals.”

Tom added that as an older brother, he is happy that his brother is pursuing his dreams. “I know that Robert wanted to do this for long. He wanted to pursue his passion and we are wholeheartedly behind him,” he added.

For Abramov, experience working with merchants coupled with marketing experience gave him the confidence to start his own shop. “I have fun working with merchants and clients and have been running an ISO shop for five years now,” he added.

Flow Rich is in the process of setting up a team and and building a lender database.

As the industry expands and catches the eye of the big banks, competition will continue to breed. “While competition is on the rise, it will finally weed out the smaller guys tarnishing the image of the industry with little experience,” Abramov said.

Is now a good time as any to enter the business?