The Scoop on iPayment’s MCA Renaissance

August 18, 2017

iPayment, a small business payment processing company, is placing a bet that it could be better the second time around in the MCA industry. iPayment Capital, which is scheduled to launch in the fall, is iPayment’s second foray into the merchant cash advance market. In conjunction with this expansion iPayment tapped Tomo Matsuo as senior vice president to spearhead iPayment Capital.

iPayment’s announcement comes on the heels of industry peers Square Capital’s Q2 loan origination of $318 million and PayPal’s acquisition of Swift Financial. Rather than remain on the sidelines, especially with access to data on some 137,000 small businesses, iPayment is making its move.

“Before Daily ACH loans and MCAs, we all started with the split payment MCA, and it’s exciting to see the recent renaissance of that mechanism with companies like Square and PayPal making it a key product feature. Transaction-based underwriting and variable payback schedules have become much more mainstream thanks to companies like Square and Amazon,” said Matsuo.

iPayment’s timing for getting back into MCAs is apparent but also coincides with the industry being held under a microscope for some questionable practices, not the least of which involves stacking, which can get small businesses in over their heads. Matsuo said the industry has a shared responsibility to fix this.

“I think there’s an opportunity for the industry to clean up some of the stacking and other practices. We all need to do more to better align ourselves with the needs and long-term health of the customers,” said Matsuo.

Meanwhile David O’Connell, senior analyst at Aite Group, offered his thoughts on the future role of MCA in small business funding: “Although we will always have merchant card advances in large volumes and these will be important to SMBs seeking funding, some of this volume will be replaced as the practices of alternative lenders become more entrenched: the provision of capital to an SMB based on a variety of data sets that achieve a fuller view of an SMB’s ability to repay only some of which is related to credit card volume.”

Balance Sheet Funder

Similar to its predecessor product iFunds, iPayment Capital will be a balance sheet MCA origination business. The company has the benefit of hindsight with iFunds, which was before Matsuo’s time there, as well as any missteps by the industry from which to pull.

“My job is to launch and build our own balance sheet MCA product, and we have a management team committed to the initiative,” said Matsuo. “iPayment is in a unique position because of our long history with the product — as a funder, split payment technology provider, and referral partner — and have a lot of experiences to build upon. There’s a great team at iPayment with a ton of institutional knowledge.”

iPayment’s access to customer data and insights certainly gives the company an edge. “It’s a crowded market going after a finite universe of customers. From a customer acquisition standpoint, iPayment has the benefit of having 137,000 customers,” said Matsuo.

iPayment also has solid industry partners including the likes of RapidAdvance with whom the company serves merchant customers. iPayment will continue to work with RapidAdvance and others on MCA. “We recently had the opportunity to strengthen our balance sheet, and we believe investing in iPayment Capital makes great business sense,” said Matsuo.

Matsuo pointed to opportunities within the smaller merchant segment for MCAs. iPayment Capital’s average funding size will be somewhere between Square Capital’s range of $6,000 – $7,000 and that of ACH alternative lenders at about $40,000. “We’ll be right in the middle,” he said.

Matsuo, a Bizfi alum, officially started in his new role on July 1, and he has no interest in looking in the rearview mirror. “At the end of the day, it comes down to pricing risk appropriately and maintaining proper controls,” said Matsuo, adding: “We all want to grow, but there are responsible ways of doing so.”

Go West, MCA Broker

August 16, 2017

If you check out the deBanked forum, one of the latest discussions originated from a self-described newbie business owner who wants to know, ‘What separates a successful ISO from the rest?’ The user, who calls himself jellyfish capital, asks the deBanked universe:

“I’m trying to figure out what the variables are that would dictate a successful brokerage/ISO vs. a shop that has a ton of turnaround and doesn’t make any money and ultimately ends up shutting its doors.”

The answer just might lie in the types of financial products the broker can sell.

MCA Broker Shift

Noah Grayson is managing director and founder of South End Capital, a commercial and investment residential real estate lender launched in 2009 that also started doing SBA loans and MCA consolidation loans in recent years to help out merchants with stacked MCA positions. Grayson pointed to a shift in the types of brokers signing up with the Encino, Calif-based lender.

“We’ve noticed a large number of brokers signing up with us are coming over from the MCA space. They’ve relayed to our staff that competition is too stiff to make enough money only originating MCAs, and they are looking for other avenues to bring in revenue,” Grayson said.

Indeed, South End Capital has seen an influx of brokers from the MCA industry gravitating their way. In fact, there has been more than a 10 percent spike year-to-date versus the same period last year in the number of brokers that discovered South End Capital through some form of Internet origin, such as deBanked, versus a targeted ad in a real estate related publication or through more traditional real estate origination means.

“What we’re hearing from our MCA industry referral partners is that their[customers] now want any option other than an MCA. These brokers are coming to us now because they are trying to evolve their businesses to stay afloat. Offering real estate or SBA loans has proved to be the next logical step for these brokers and it has provided a big bump to our business,” said Grayson.

As in any industry, making a career change can introduce unexpected challenges. A hurdle for the brokers, particularly as it relates to making the jump to commercial real estate lending, has been unrealistic expectations.

“Many MCA brokers have an expectation that real estate or SBA loans will work similarly to an [MCA], but it’s a more involved process. There’s more documentation and more moving parts to understand. There has been a big learning curve for a lot of these brokers — some have been willing to learn and are excited about the opportunity. However, many MCA brokers have proven extremely resistant to change and unable to adapt” noted Grayson.

There are hurdles facing the MCA industry, too.

Merchant Motivation

Merchant Motivation

So what’s driving the shift? Small businesses, some of which are saddled with short-term obligations, have begun to realize that thanks to the rise of alternative lenders they have more options. Meanwhile unscrupulous collection agencies are throwing a monkey wrench into the situation, making it trickier for merchants to gain access to cash advances.

David Soleimani, CEO of LendFi Corp, said a major setback for the MCA industry has been the interference of collection companies convincing good paying merchants to default and cut their payments in half. By negotiating payments with a third party, merchants essentially become blacklisted from receiving any further MCAs.

LendFi senior account rep Jonathan Meyer specializes in cash advances, term loans, equipment leasing and lines of credit. He’s noticing a trend of more MCA brokers expanding their line of business in the last year.

“Companies are overextended [with cash advances.] It’s a problem,” said Meyer. “If everything is perfect, we can do a term loan or a line of credit if it falls under certain criteria.”

One small business came to LendFi’s Meyer recently and as a result saved himself a lot of cash. “I consolidated someone’s loan recently. I got him a term loan and saved him $14,000 a month. He had two loans at $110,000. I got him a term loan for $165,000 and he saved $14,000 a month. He was paying $22,000 per month,” said Meyer, adding that he also consolidated the payments from a daily to a monthly schedule. “That’s a huge savings,” he said.

For all of the twists and turns that may be up ahead for brokers and merchants alike, one thing seems clear. The MCA industry isn’t going anywhere.

“There will always be a [customer] whose only option is an MCA, and it has its benefits for many. For example, the only way to get business funding in one or two days is with an MCA. However, I think the reasons why someone would need an MCA are becoming fewer and fewer as other more viable financing options emerge,” said Grayson.

Is The End Near For This Debt Settlement Firm?

August 11, 2017 Corporate Bailout, a New Jersey based firm that purports to help businesses lower the monthly payments on their debts, is back in the news. This time it’s for allegedly running a sex-fueled office with stripper parties, sex dolls, and sexual harassment, according to the New York Post who published video footage of the debauchery. Warning: the New York Post link is not safe for work.

Corporate Bailout, a New Jersey based firm that purports to help businesses lower the monthly payments on their debts, is back in the news. This time it’s for allegedly running a sex-fueled office with stripper parties, sex dolls, and sexual harassment, according to the New York Post who published video footage of the debauchery. Warning: the New York Post link is not safe for work.

deBanked has written about Corporate Bailout previously, in one case recently where the company is alleged to be robo-dialing out of control. Corporate Bailout never responded to the lawsuit and the court entered a default against the company this past Monday, according to the docket.

Back in April, deBanked also received the recording of a call purportedly between a representative of Corporate Bailout and a small business owner. We had the lengthy dialogue transcribed and it appears below with the names between the parties changed.

Of note, the alleged Corporate Bailout representative in the call makes several references to a partner law firm named Protection Legal Group. There are several lawsuits pending against Protection Legal Group, one of which alleges the firm didn’t have a lawyer licensed to practice in the state they claimed to offer defense in. In that situation, a merchant had to hire another lawyer to sue his lawyer at Protection Legal Group.

| Person Answering Phone: | Hello. |

| Robo Agent: | Hello. How are you today? |

| Person Answering Phone: | I’m good. |

| Robo Agent: | Great! Can I speak to the business owner please? |

| Person Answering Phone: | Who is this please? |

| Robo Agent: | This is Alex from Corporate Bailout. Are they available? |

| Person Answering Phone: | Yeah. One second please. One second. |

| Robo Agent: | Thanks. |

| John: | Hello. |

| Robo Agent: | Can I speak to the business owner please? |

| John: | Speaking. |

| Robo Agent: | This is Alex from Corporate Bailout. I know your time is valuable. So, let me get straight to the point. We help small business owners eliminate their unsecured debts. If your business has taken a merchant cash loan or advance, a high interest credit card debt, accounts payable debt, or any other unsecured business debt, you are now able to settle your outstanding balances for just a fraction of what you owe. I just need to ask two qualifying questions. Okay? |

| John: | Sure. |

| Robo Agent: | What type of entity is your business registered as? LLC, Corp, etc.? Hello? |

| John: | LLC. |

| Robo Agent: | Do you have at least $25,000 in unsecured debt? |

| John: | Yes. |

| Robo Agent: | Great! It looks like you may qualify. Hold on one second while I get a specialist on the phone who can explain further. |

| [Phone Ringing] | |

| Derrick: | Hello. Hi. |

| Robo Agent: | Hi, I have someone here that is interested in moving forward. I will let you take it from here. |

| Derrick: | Thank you for that. My name is Derrick by the way. Who am I speaking with? |

| John: | John. |

| Derrick: | John, it’s a pleasure, John. So, John, go ahead and tell me a little bit. What kind of unsecured debt are you experiencing? Is this with cash advances? |

| John: | Yes. |

| Derrick: | All righty. And that’s our cup of tea. So, I wanna give you an example— |

| John: | What exactly— |

| Derrick: | …of exactly how this would work for you. |

| John: | Okay. Perfect. Yeah. |

| Derrick: | All right. Tell me how many advances do you have. Do you have one or a couple out there? |

| John: | I have 3. |

| Derrick: | 3. Okay. And what do you owe approximately in combined balances? |

| John: | About $85,000. |

| Derrick: | Okay. And lastly, what are they charging you daily? |

| John: | Total of about $2,000. |

| Derrick: | At this day? |

| John: | Yeah. |

| Derrick: | Okay. Obviously, they’re overextending you for sure. Now, you open these advances yourself? Is this your business, John? |

| John: | Yes. |

| Derrick: | Okay. What is it that you do? I just wanna get a better grasp of what’s going on. |

| John: | We’re a trucking company. |

| Derrick: | Oh okay. Yeah. Yeah. I work with a lot of trucking clients. All right. So, here’s the deal. I mean, at 85,000, knowing that these are cash advances, we’re able to reduce that down to about 63,000. Saving you well over 21,000 just on principal. |

| John: | How do I do that? |

| Derrick: | That’s very simple. I mean, what we do is we appoint you a power of attorney that represents the association. And what they’ll do is that by power of attorney they’ll contact your creditors in a form of hardship for you. Okay? And that’s the key word there because by law— And it doesn’t matter if it’s a cash advance or a Capital One Visa. Whoever that creditor is, whatever obligations you have to that creditor comes to an immediate halt. That means no more interest accruement. That means that whatever number I’m telling you by the time you hire us let’s say by today, that’s the number. Yeah. |

| John: | One second. Why does it come to a sudden halt if I have a contract with them? Like can’t they sue me for this? I mean, I signed a contract with them and everything. How is it legal to go and say that I can’t pay them? I’m not understanding you. |

| Derrick: | Well, #1, these are cash advances, which is highly unregulated. Everyone knows if you look into it. Okay? Everyone knows— |

| John: | I did. |

| [Crosstalk] | |

| Derrick: | Okay. Yeah. There you go. Well, they’re tiptoeing the line of legalities here by pressing [0:04:55][Inaudible] laws. That’s why we’re able to snatch them and nip them in the butt. Okay? When you are charging on a daily basis an overextended amount way past 25% APR, this is abuse. This comes to abuse now and we have to come at them in a form of hardship. By law, that’s what happens and everything comes to a halt right then and there. Now, they have to settle. Now, here’s the thing. I know you’re saying can they sue you. You know, they can. They can. Probability is very low. |

| John: | Why would I take the risk of getting sued? I mean, I’m just trying to understand. Is what you guys doing also legal? I mean, no offense, it sounds a little— |

| Derrick: | Oh yeah. |

| John: | This sounds a little less legal. What you’re doing sounds a little more illegal than what they’re doing because I really have a contract with them that I signed and I notarized. I mean, that is like legal documents. |

| Derrick: | Yeah. We give you a legal contract. It needs to be notarized and all that too. Okay? But here’s the thing. It is legal here. You’re working with the law firm. Okay? The law firm will then take that responsibility and make sure that they do reduce your debt size. Okay? It’s a cash advance. It’s a slam dunk every time. Who do you work with by the way? |

| John: | [0:06:15][Inaudible] I’ll give it to you in a couple minutes. Where did you get my information from? ‘Cause I usually get calls from them. Like this is the first call I’m getting from this type of company. Where did you guys get my information from? |

| Derrick: | So, we essentially look through UCC filings and UCC filings are only liens that are basic entry companies that normally take out cash advances. Normally. |

| John: | Right. |

| Derrick: | 9 times out of 10 when I see a UCC file that looks like yours and, you know, I’m usually right it’s a cash advance, so yeah. |

| John: | Which business were you referring to though? |

| Derrick: | I don’t know. I don’t know. Your phone call got transferred to me. So, we have several ways of finding new clients and one of them is that we have a database. People make outbound calls. I’m the one on the receiving end. I work with my clients one-on-one to get them enrolled, have them feel good about the program, and then I pass them along to the law firm. That’s my role here. So essentially, it happens like this, John. Right? Let’s say hypothetically today you’re like “You know what? This makes sense. I am in a hardship. I need to get out of this crap. All right, what do I need to do today?” I get you on board today just hypothetically. By Thursday because today is Tuesday— We need at least 48 hours. By Thursday, the law firm contacts you and they say, “You know, John, we reviewed everything. You know, you’re good to go. Let’s now help you stop making those payments so that way your bank no longer honors the ACHs you’re making daily. So essentially, by Thursday, we’ll put a stop, a complete halt to your payments. And then we can culminate maybe a week to 2 weeks before there’s any expense. And by the way, it will be a fraction of that cost. We’re talking at least 50% less in those payments. That’s how overextended they have you on. We don’t have to have that start for at least 2 weeks from today or whenever— |

| John: | So, in essence, I will still have to pay them. Just in a longer period of time you’re saying? |

| Derrick: | Right. Yeah. Well, we can work that out, but the whole point of this program is not to stress anybody. And that’s where the idea of a scam needs to be thrown out of the window. Okay? |

| John: | So, they’re scamming me you’re saying? |

| Derrick: | Yeah. I would say so. You don’t feel like you’re being highway robbed right now paying 2,000 a day? And I can give you even better numbers if I look at— you know, if I take a peek at the contract just to see the real numbers ‘cause on average they’re charging anywhere from 30 to 60 percent on a borrowed amount. That’s an average. I know you’re in that category. |

| [Crosstalk] | |

| John: | I understand, but I didn’t know about it that’s why I’m saying if I knew about all this, I can’t deny in court if they sue me. They do have a legal document against me. I mean, it is an issue. |

| Derrick: | Right. Well, here’s the good thing. I mean, people are in such a worse shape than you, John, that they’ll hire any company who’s gonna promise them that they’ll be able to negotiate, but the greater thing why this is such a more wise decision for you is that you’re not hiring a middle man. As a matter of fact, I can show you, okay, any agreements that we have. We provide litigation defense services on top of the settlement. So, if ever anything should happen, which being at 85,000 likely not, but if ever anything should happen, you have attorneys there that will show up in court for you, that will battle, that will counter lawsuit if we have to, whatever, drag out the process, whatever it takes. Whatever it takes. But at the end of the day if they wanted to sue you, you know how long a sue takes place or takes to convert? |

| [0:09:59] | |

| John: | I know, but— |

| Derrick: | It takes a long time. |

| John: | At the end of the day, I would still be found guilty that I did sign the contract. What defense could I possibly have for that? I’m just trying to understand what the legality is. |

| Derrick: | The defense is #1 it’s a hardship. If you look into that, hardships create a big deal in the law system. So, that’s #1. Number 2 is that this is technically not even a debt that you have. Check in on technicalities. They only purchase future receivables at expect it let’s say 2,000 a day. |

| John: | Yeah. And they also have a judgment against me though. |

| Derrick: | That is all scare tactics. That’s all. Confession of judgments you’re talking about, right? |

| John: | Yeah. Yeah. |

| Derrick: | Confession of judgment that you signed. Yeah. Yeah. Almost everybody signs a confession of judgment now. They just started implementing that the last 3 years. |

| John: | They can’t do anything with that? |

| Derrick: | Not when you have a power of attorney reaching out to them for settlement against the hardship cost. They can’t do that. |

| John: | Oh. |

| Derrick: | And if they use that– |

| John: | And also like with this document, they can like freeze accounts and they can freeze assets and stuff like that. But if you guys trick them and they can’t do that– |

| Derrick: | Yes. They won’t be able to. But if we need to take any preventative actions, your law firm, your adviser there will tell you to possibly change. |

| John: | So, you guys have a lawyer? You are the lawyer then? |

| Derrick: | I’m not the lawyer. I’m not the lawyer. I don’t do the negotiation. I told you my role here is just to get you on board so I can pass you to the law firm. That’s it. That’s my role. Give you the information– |

| John: | what’s your charge? |

| Derrick: | Okay. Good question, John. So, let me look at this number here again. I wanna give you something real. So let’s say it’s 85, right? 85,000 you owe. That gets reduced down to $63,340. That 63,000 is going to cover absolutely everything. That covers paying back your cash advances. That will cover for our services and fees all inclusive. Okay? The only reason why we’re able to do that, John, is because we are a nationwide law firm that does negotiations for cash advances specifically. That’s what Protection Legal Group does. And so, are you familiar with a class action lawsuit? Are you familiar with that? |

| John: | Yeah. |

| Derrick: | Okay. So, we approach settlements in that same format. Class action settlement is what we call it. So, essentially you’re one drop in the ocean. Right? And that’s why I wanted to ask you who you work with so I can give you references. But guaranteed we have, you know, up in the hundreds of clients in those cash advances that we have already control such a large portion of their funds. So, because we’re going to– Who do you have? do you have Swift? [inaudible] |

| John: | I’m not gonna reveal that information yet until I look into your company a little more only because it’s my first time hearing about this. I will look into this. I wanna speak with my lawyer about it and everything. But you were telling me it would be lowered to 63,000. That’s fine. |

| Derrick: | Yeah. That’s at most. |

| John: | What’s your fee? |

| Derrick: | Our fees are inclusive, John. I can’t tell you what it is until we submit everything, until we submit all the hard copies into the law firm |

| John: | What’s the percentage range? I mean, there’s gotta be some sort of number that I can go by. |

| Derrick: | Yeah. Yeah. I can give you a percentage. So, let’s say we reduce it down to 70 cents on the dollar, right? 42 cents of the dollar will go to your creditors. Okay? |

| John: | And the 28? |

| Derrick: | And 28 cents gets [0:13:58][Inaudible] up between the law firm and your attorney. It’s like 4 cents in a dollar to the attorney, 24 cents to the law firm. So, that’s how it works. Normally, that’s what they look to negotiate. |

| John: | So, you’ll get the 24, they get the 4? |

| Derrick: | That’s if they agree to that term. Yeah. The whole point is for your attorney to figure that out with the lender. At the end of the day– |

| John: | Isn’t that 24% on the dollar also? |

| Derrick: | No. No. On the 70 cents on the dollar that we reduce it. So, you have 85,000. Reduce it to 70 cents on the dollar let’s say. In that 70 cents, 42 goes to them. The remainder of the 28 is split. Right? 4 cents to your attorney, 24 to the law firm. So that’s the numerology of how it gets distributed. |

| John: | That’s 40% |

| Derrick: | Right. That’s how it gets– What is? |

| John: | The 28 cents on the 70 cents is 40%. |

| Derrick: | 40%? |

| John: | Yeah. |

| Derrick: | No. No. It’s smaller than that. |

| John: | Do the math. |

| Derrick: | If it were 40%– |

| John: | Do the math. You said 28. Do 28 divided by 70. |

| Derrick: | 28 divided by 70, 0.4. Yeah. 40%. So, what are we getting off here? |

| John: | So basically, you’re charging me 40% and they’re charging me the same 40%. So what’s the difference? I’m just trying to understand why– |

| Derrick: | No. Yeah. We’re making 40– Hold on. We’re making 40% of that 70%. They’re making 60% out of that 70 cents. I mean, if you wanna get in detail, that’s what it works down to. At the end of the day, the whole program cost for you is only 63,000. So, you make the decision whether you pay 63,000 or 85,000. |

| John: | And run the risk of getting sued. |

| Derrick: | No one touches–. No. You have a law firm that will fight and give you the litigation defense. |

| John: | Right. That’s not a–I understand that. I understand they’ll give it to me. But I also run the risk of losing. And if I lose, I would have to pay all their legal fees and that extra money that I know, you know, what trying to get out of. So, here’s what I’m gonna do. I’m gonna have to look into this a little more ’cause I’m not just gonna give all my information in a second. Can you send me some– |

| Derrick: | Yeah, that’s fine. |

| John: | …information so I can look it over? |

| Derrick: | What’s your best email, John? |

| John: | It’s [address redacted] |

| Derrick: | @gmail.com. Do you happen to be in front of a computer now? |

| John: | I do. Yeah. |

| Derrick: | All right. I just wanna make sure that you at least get it. I’m putting in the subject heading, ATTENTION John. This should be easy to find. So, you know, you can loo at– |

| John: | I just wanna make sure what it’s about. what is this for? What’s it called? |

| Derrick: | Debt relief I can put in there. Is that okay? |

| John: | Yeah. That’s fine. |

| Derrick: | I’ll put debt relief as well. Yeah. |

| John: | And this is from Mason & Hanger? |

| Derrick: | Mason & Hanger? |

| John: | Yeah. That’s where you’re calling from? |

| Derrick: | What’s that? No. No. Protection Legal Group is the name of the law firm. Protection Legal Group. |

| John: | Oh, it’s not Mason & Hanger? |

| Derrick: | No. I don’t know where you got that name. |

| John: | From the caller ID |

| Derrick: | Really? Mason & Hanger? I don’t know. That’s strange. You know, when I make calls out of the office, sometimes it comes out like– |

| John: | Are you gonna have your contact number over there or no? |

| Derrick: | Yeah, it’s in the email. Tell me if you have it now ’cause it says that it’s sent |

| John: | [Name redacted]? |

| Derrick: | [Name redacted]. Yup. that’s me. All right. So, there’s a summary of what we went over and then those things in bold would be what we need in order— if you wanna proceed forward, but the very first thing you’ll see in bold is the current cash advance agreement signed or unsigned. Very important. That’s what’s gonna help us approve you or not and see if we can fit you in the program. We have to look over the verbiage in there. You see one document attached. Right? |

| John: | Right. Right. |

| Derrick: | Do you see what’s in bold? Yeah, I have a few things in bold there that we require from you. Okay? The hardship letter is one of them that’s attached in there. But before all of that, we wanna take a look at a copy of the agreements you have with the 3 cash advances. It could be signed or unsigned. Your personal information is not gonna do us any good. We wanna see if we can approve you first. Okay? That’s all. It’s just by procedure. And then what we find in there, which only takes about 20 to 30 minutes to approve you, I can tell you, “Hey, John, you know, here are the real numbers, what we found based on your contract. Here’s what we can offer and here are your options.” And then we can come into an agreement together. The whole point of this is to get you off from paying— You’re paying 10 grand a week, man, you know. To get you off of 10 grand. Maybe down to 5,000. Whatever that number is that’s more comfortable for you and obviously is realistic for the law firm. Okay? |

| John: | You are basically just the broker for the law firm? |

| Derrick: | I’m their spokesman, you know. I’m their marketing arm. Not a broker or anything. If I were a broker, I’d have countless sources of different law firms that does this. |

| John: | I assume you have one law firm that you work with? |

| Derrick: | I only represent them. |

| John: | Who do you work with? |

| Derrick: | What was that? |

| John: | Who is the law firm that you work with? |

| Derrick: | Protection Legal Group. Protection Legal Group. You can put that down. |

| John: | Can you email me that information? I wanna make sure. It is in the email? |

| Derrick: | Yeah. It’s in the email. Yeah. Yeah. It’s all in there. |

| John: | Okay. Protection Legal Group |

| Call trails out into goodbyes… |

In the follow up email that came up from a corporatebailout.com address, Derrick said, “We have teamed up with nationwide law firm, Protection Legal Group, who will negotiate with lenders on your behalf. By enrolling in our program, we would reduce the total advance balances down to 70 cents on the dollar! But more importantly, we turn your daily payment into a ONCE a week payment, and reduce that amount by up to 50%!”

Damage From the Nulook Capital Bankruptcy Shows Up In GWGH Earnings

August 10, 2017In April, we reported that Nulook Capital, a boutique merchant cash advance funder on Long Island had declared Chapter 11. The move was seemingly a response to a lawsuit filed against them by a secured creditor, GWG MCA, a subsidiary of publicly traded financial services company GWG Holdings Inc. (NASDAQ: GWGH).

In that bankruptcy, a merchant cash advance marketplace known as PSC also filed a claim against Nulook Capital to the tune of $400,000 in outstanding debt. In a sudden twist, however, a court saw enough evidence to believe that Nulook and PSC had an interwined relationship that jeopardized GWG MCA’s collateral, and ordered that PSC, who was supposed to just be a creditor with a secured claim, be put into receivership.

While the battle between all of the parties is still playing out in court, GWG Holdings Inc. disclosed the damage in their latest quarterly earnings report.

The secured loan to Nulook Capital LLC had an outstanding balance of $2,060,000 and a loan loss reserve of $1,478,000 at June 30, 2017. We deem fair value to be the estimated collectible value on each loan or advance made from GWG MCA. Where we estimate the collectible amount to be less than the outstanding balance, we record a reserve for the difference. We recorded an impairment charge of $870,000 for the quarter ended June 30, 2017.

Also notable in the earnings statement is that GWG MCA funds merchants directly. The company booked $133,583 in revenues attributed to MCAs in Q2. The amount was negligible compared to their core life insurance business. Their stock is up more than 30% YTD.

Beneficiary of NAB/TMS Deal Could Be Rapid Capital Funding

July 14, 2017 Square is not alone in offering working capital to their payment processing customers. Troy,MI-based North American Bancard (NAB) has been offering their customers merchant cash advances through a Troy-based subsidiary known as Capital For Merchants (CFM) for more than 10 years. And after seeing the growth of that segment, NAB went out and acquired Miami,FL-based Rapid Capital Funding (RCF) in late 2014.

Square is not alone in offering working capital to their payment processing customers. Troy,MI-based North American Bancard (NAB) has been offering their customers merchant cash advances through a Troy-based subsidiary known as Capital For Merchants (CFM) for more than 10 years. And after seeing the growth of that segment, NAB went out and acquired Miami,FL-based Rapid Capital Funding (RCF) in late 2014.

Now, NAB has become even bigger by acquiring Total Merchant Services to make them the seventh largest payment processor in North America. The new combined company, which will operate under the NAB name, will rival Square in annual processing volume.

One beneficiary of the deal could be RCF, who merged with CFM earlier this year. RCF has historically had a sizable direct sales operation that facilitated financing for all merchants, regardless of whether or not they processed payments with NAB. That continued until recently when they reportedly pivoted towards focusing more of their new origination efforts on NAB’s (and now combined with TMS’s) 350,000+ merchants.

RCF was founded nearly 10 years ago. They acquired Anaheim,CA-based rival American Finance Solutions in the fall of 2014, right before joining the NAB family.

Need Leads This Summer?

July 13, 2017 I am often asked for referrals on things like lead sources. Fortunately our website already has quick cheat sheets on who to call for your everyday merchant cash advance and business lending needs. Below is a link to a few of them:

I am often asked for referrals on things like lead sources. Fortunately our website already has quick cheat sheets on who to call for your everyday merchant cash advance and business lending needs. Below is a link to a few of them:

Accountants and auditors familiar with the industry

Industry attorneys – it’s pretty common for a firm to have an area of focus so they’re already categorized

Conferences we’re attending in 2017

Past digital issues of our magazine

I hope you find this helpful!

What Happened to Bizfi?

July 1, 2017

Update 9/22: Select assets of Bizfi including the brand and marketplace were acquired by rival World Business Lenders

Update 8/30: Credibly was selected to service Bizfi’s $250 million portfolio

This past week, Bizfi gave their remaining employees a 90-day warning notice, according to sources familiar with the matter. It was the latest wave of layoffs to hit the company over the last few months. At its peak, Bizfi, which provided capital to small businesses, employed more than 200 people. Some of those riding out their potentially last 90 days are anxiously awaiting the outcome of nonpublic negotiations to salvage parts of the company’s legacy, if it can be done at all.

It’s a bittersweet moment, according to newly former employees I spoke with, some of whom are so young they vaguely recall Bizfi’s past as both Merchant Cash and Capital (MCC) and Next Level Funding (NLF). They characterized their experience as having worked in fintech.

MCC was founded in 2005 as a buyer of future credit card sales, way before the rise of modern fintech. They later spawned affiliate company NLF, which was eventually consolidated into the newly minted Bizfi brand in 2015. In 2016, they were one of the top three largest originators of merchant cash advances. Today, they are no longer funding new business.

Overall, the company grew too fast and missed the window of opportunity to sell, observers maintain. In a CNBC interview in 2015, a Bizfi representative said that they believed securing a major equity investment would allow them to go public by 2017. Such an investment never came. And with the market cooling last year, institutional interest in the space waned and several of the industry’s better-known players were forced into a precarious position.

Bizfi held on, until recently.

I myself was the third employee of MCC, or fourth depending on who actually walked through the door first on my first day that I shared with another new hire back in 2006 (who by the way was Jared Feldman, the eventual co-founder and CEO of Fora Financial, which sold for millions to Palladium Equity Partners LLC). I was at MCC until 2008 and then worked at NLF until 2010. That means I had been gone for five years before the companies ever merged to become Bizfi and seven years before the current dilemma. Therefore I’m not able to personally comment on what exactly went wrong because the company was nowhere near the same as when I left it.

I will report new developments as they become public.

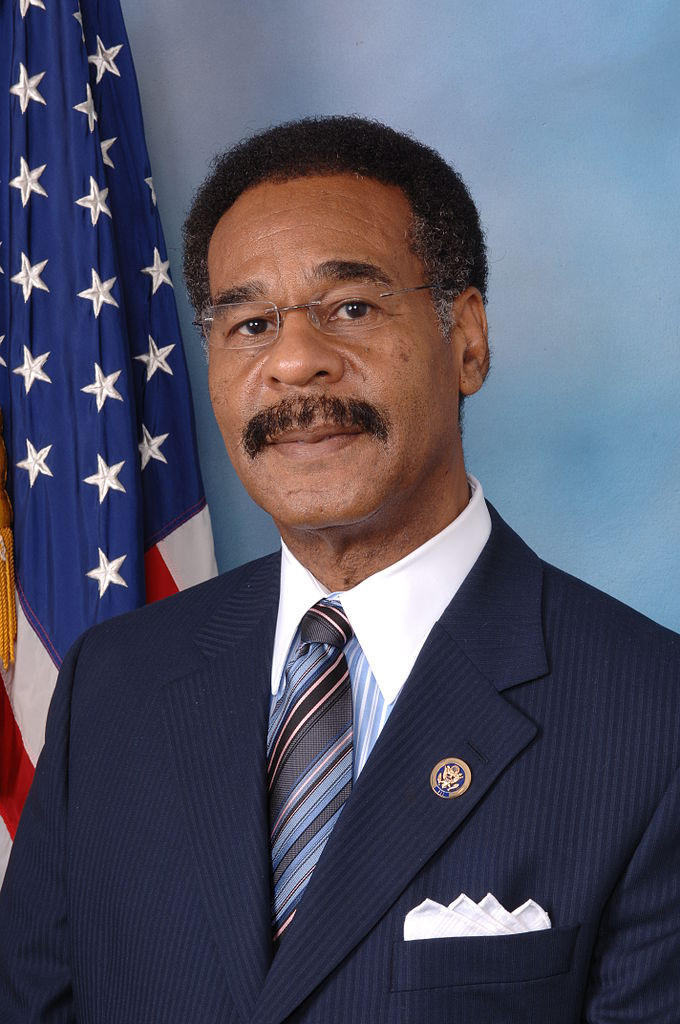

Congressman Emanuel Cleaver, II Makes Inquiry Into Merchant Cash Advances

June 26, 2017 A US Congressman from the fifth district of Missouri is conducting an inquiry into “Fintech Lending,” according to a statement posted online. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, II published letters that his office sent out last week to five companies seeking information on how they avoid discriminatory lending practices in small business lending.

A US Congressman from the fifth district of Missouri is conducting an inquiry into “Fintech Lending,” according to a statement posted online. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, II published letters that his office sent out last week to five companies seeking information on how they avoid discriminatory lending practices in small business lending.

An excerpt:

I have recently launched a review into FinTech small business lending. I am particularly interested in payday loans for small businesses, also known as “merchant cash advance.” The payday loan industry has often targeted communities of color with high rates and fees, and Congress needs further information that small business payday lending is operating with transparency and free of discrimination

Ironically, two of the five recipients, Prosper and LendUp, don’t even operate in the small business space, so how exactly they were selected remains a mystery.

Only two of the five companies have any connection to merchant cash advances, but the Congressman’s connection between them and payday loans is perplexing nonetheless.

The subject matter at hand, however, is similar to another fact-finding endeavor that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is conducting as part of its mandate under Dodd-Frank.

A response is not required but the Congressman asked the recipients to respond by August 10th.