Missed Broker Fair? Get the Kit and Presentations

May 21, 2018

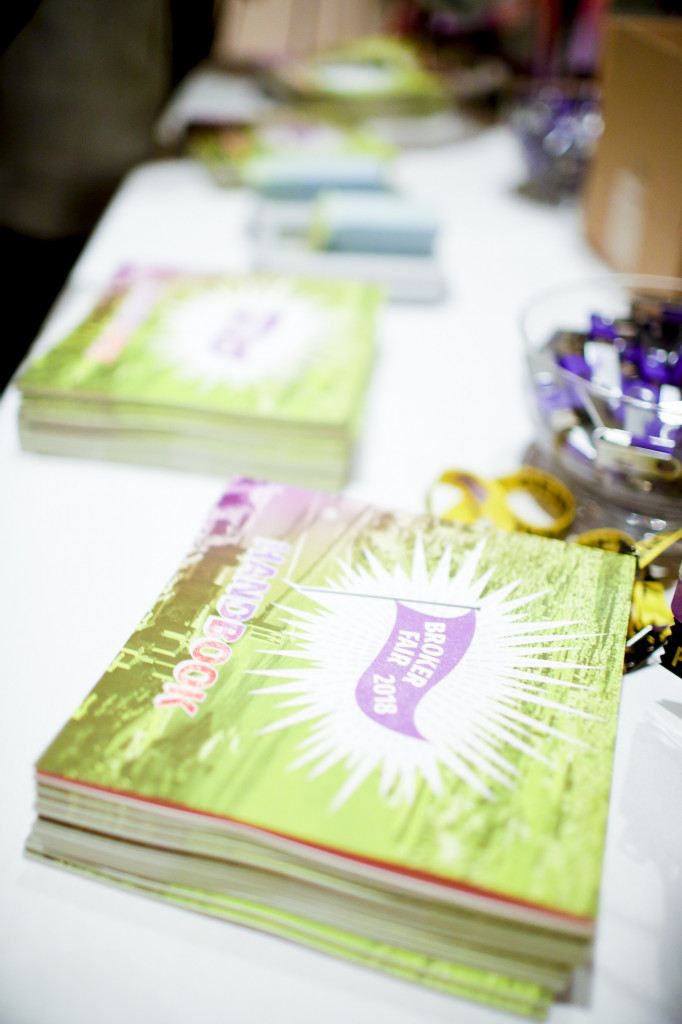

If you missed Broker Fair, you can still get your hands on some of the gear and the presentations. Simply email info@brokerfair.org and ask to be shipped a copy of the Broker Fair Kit. The accessories, which will only be provided while supplies last, include a USB drive with the day’s presentations, a Broker Fair bag, a Broker Fair shirt, a deBanked magazine, a Broker Fair handbook, and more.

Also, don’t wait too late to REGISTER for deBanked’s half-day event in San Diego on October 4th. deBanked Connect: San Diego will connect funders, brokers, and folks from the industry for networking and cocktails!

Broker Fair 2018 Story Continued

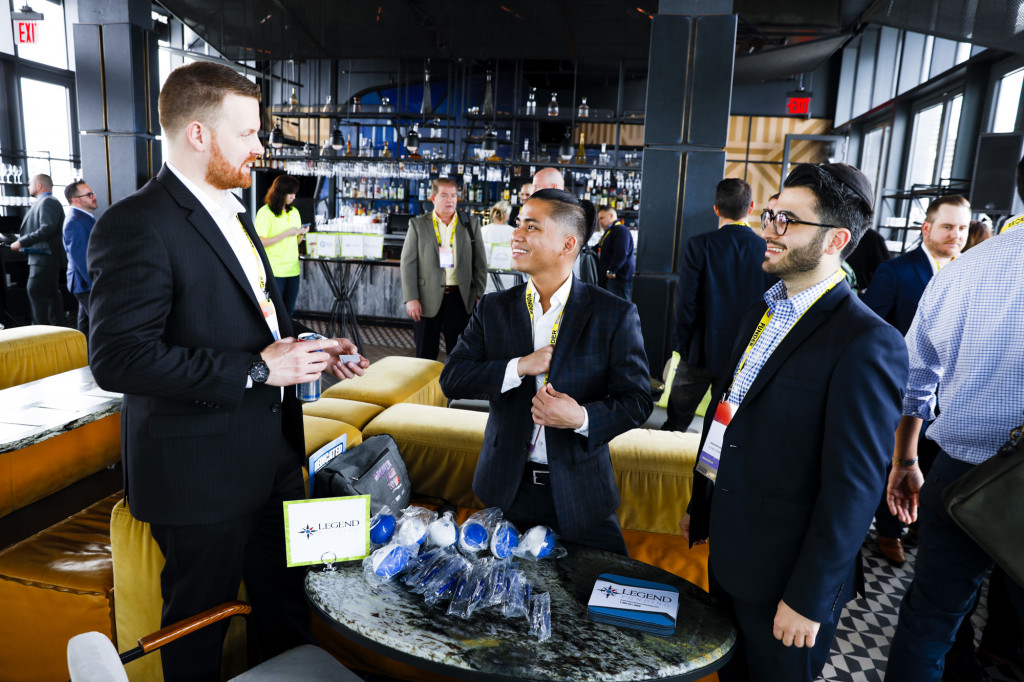

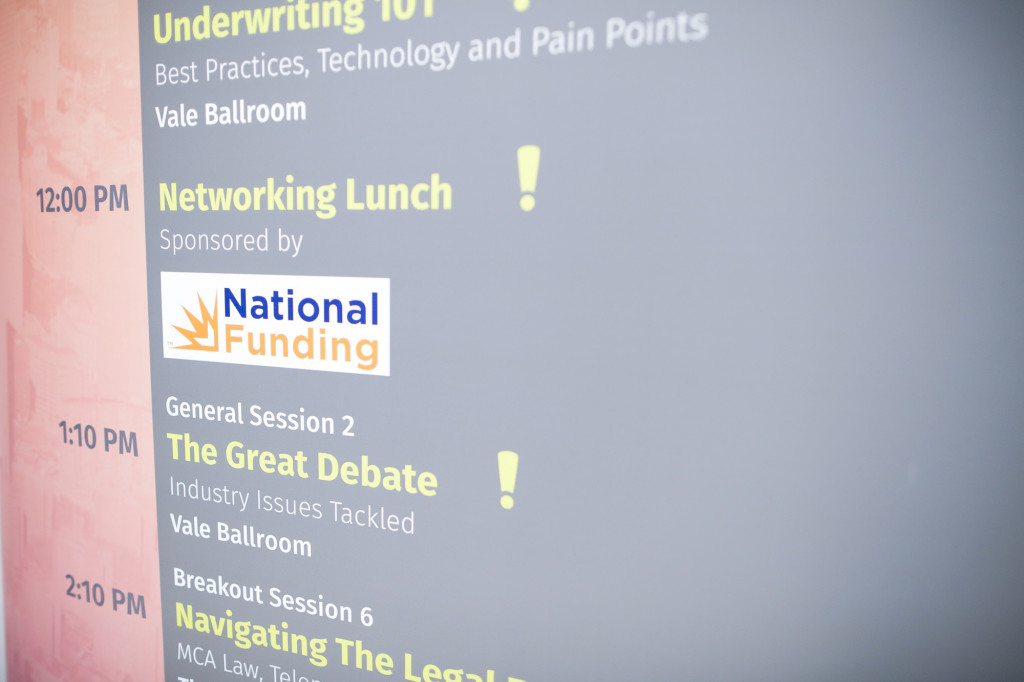

May 18, 2018A continuation of Broker Fair 2018 through photos:

We’ll publish the entire cache of them in the coming weeks.

JOIN US OCTOBER 4TH IN SAN DIEGO AT THE ANDAZ FOR A SPECIAL HALF-DAY INDUSTRY NETWORKING EVENT

Couldn’t find yourself in any of our photos? We’ll publish the full album in the following weeks.

The Broker Fair 2018 Story Through Photos

May 18, 2018Broker Fair 2018 was an amazing day of inspiration, education, and opportunities. We’ve posted some of our photo footage below:

JOIN US OCTOBER 4TH IN SAN DIEGO AT THE ANDAZ FOR A SPECIAL HALF-DAY INDUSTRY NETWORKING EVENT

Couldn’t find yourself in any of our photos? We’ll publish the full album in the following weeks.

Broker Fair 2018 Pre-Show Photos

May 17, 2018Photos from the Broker Fair 2018 May 13th Pre-show party at The William Vale in the Vale Garden Residence. Photos from the conference will be published separately. We hope you had fun.

SBFA Launches Broker Council

May 11, 2018

The Small Business Finance Association (SBFA) announced today the launch of a new initiative called the SBFA Broker Council designed to create and implement a set of best practices for brokers of alternative funding products.

“I think this would create two playing fields,” said SBFA member and CEO of United Capital Source Jared Weitz. “A playing field where a group belongs to this association and we understand that that group is acting in best practice, and another group that is acting on their own behalf, and we hope that they’re acting in best practice, but we can’t verify it. Folks in our group we can verify.”

Weitz and James Webster, CEO and co-founder of National Business Capital, are spearheading the SBFA Broker Council. They are the co-chairs and are in the process of selecting a board of other brokers.

What would membership in the SBFA Broker Council mean? It would mean abiding by a set of best practices. Weitz told deBanked that he and Webster would like to implement background checks on owners of brokerages and would like to make sure that brokers are storing data in their offices properly so that merchants aren’t vulnerable to having their private information stolen and abused.

They also want to make sure that brokers have the appropriate licenses in states that require them, that fees are being explained to merchants transparently and that merchants are not being triple or quadruple funded at once, “hurting the cash companies and the merchants,” Weitz said.

Membership in the SBFA Broker Council would require SBFA membership. Current members include funders, ISOs/brokerage companies and vendors that are active in the alternative funding space.

“To participate, we want members,” said Jeremy Brown, Chairman of the SBFA. “We want to give [broker members] sort of our seal of approval, and we want to know that they’re going to represent the ideals we stand for.”

Brown said that brokers have a reduced membership fee: $475/month for smaller brokerages and $950/month for larger ones.

Brown, who is also Chairman of RapidAdvance, a funding company, said that having membership in or an organization that has a set of standards would give him comfort as a funder.

“[This] would give me a lot of confidence that you’re a good actor,” Brown said, “because one of the problems in the industry is that you do have people in an unregulated business that do unethical things. So knowing who to deal with is really important and valuable.”

The SBFA is a non-profit advocacy organization with a mission to educate policymakers and regulators about the alternative funding business. According to today’s announcement, a goal of the SBFA Broker Council is to promote brokers who act fairly. But how could a third party association advance a broker’s career?

Weitz said:

“We would be able to have a badge on our email and on our website that says we are SBFA broker approved, meaning that anyone who’s a part of this council…would be on the [SBFA] website so we can build credibility when we’re on the phone with a merchant. We can say, ‘Hey, you probably spoke to three or four different brokerage shops today. It’s prudent to do that…however, let’s make sure that the ones you’re talking to belong to this association because those are the ones that are going to act on your behalf, the right way.”

FinMkt Launches ISO Business

May 10, 2018

FinMkt has launched a broad ISO, working with referral partners from brokers to accountants to small business advisors. With two years of experience facilitating consumer lending, the company has just entered the small business lending market.

“We took the same engine that we used on the consumer side and we rolled it over to the small business side,” said FinMkt’s VP of Business Development who is overseeing this new division, called Bizloans.

The Bizloans brand within FinMkt started at the end of last year, but has been in stealth mode for the last three to six months, Sklar told deBanked. So far, Bizloans has facilitated $15 million in loan application requests over the last 60 days. Of this, roughly $5 million has been funded.

The new division can present small businesses with a variety of financing, from merchant cash advance to factoring and lines of credit. In the few months that FinMkt’s Bizloans has been in operation, Sklar said that real estate asset-backed loans, equipment leasing and merchant cash advance has made up the bulk of the funding products facilitated.

For MCA products, $35,000 has been the average request and $150,000 has been the average for equipment leasing. According to Sklar, some of the funding companies that Bizloans has already worked with include OnDeck, Gibraltar, SOS Capital, 6th Avenue Capital and the San Diego-based bank holding company, BofI.

For successfully funded deals, Sklar said that they will get paid a commission and then pay the broker, depending on how involved they were in the deal.

“The commission splits vary depending on the amount of legwork and the amount of sophistication [the broker has] in the industry,” Sklar said.

For deals where the broker did most all of the work and simply used Bizloans as a platform, those brokers will generally get 80% of the commission, Sklar said. If the broker only supplied the lead, then they may only get 40%. Bizloans offers training to brokers less familiar with the industry.

Founded in 2011 by CEO Luan Cox and CTO Sri Goteti, FinMkt initially operated in the crowdfunded securities space. The company of 15 people is headquartered in New York City and has an office in Hyderabad, India.

World Global Financing, Inc. Declares Bankruptcy

May 9, 2018World Global Financing, Inc., a Florida-based merchant cash advance provider, filed for bankruptcy yesterday, according to Chapter 11 documents obtained from the Southern District of Florida.

Company CEO Cyril Eskenazi reported that its assets and liabilities were both between $10 and $50 million. Among the company’s creditors are ACH Capital, LLC, Capital One, Eaglewood funds, MB Financial Bank, the IRS and other tax authorities, WG Financing Inc, WG Funding Trust, Wilmington Savings Fund Society, FSB, several law firms, a mortgage company and more.

Gale Force Twins

April 24, 2018

As Hurricane Irma swept through the Caribbean and barreled toward the Florida Keys early last September, Wendy Vila, chief executive, at Unicus Capital evacuated her home in West Palm Beach and decamped to Panama City in the Florida panhandle where “it was just a little bit rainy.”

After safely waiting out Irma, she says, her return south was precarious. The roads were strewn with tree branches and other debris. Fuel was scarce. Many gas stations were either closed or posted signs reading “No Gas.” “Restaurants had run out of food,” Vila adds, “so there was nothing to eat” along the highway.

She returned to West Palm Beach but didn’t stay long. Instead, Vila again drove west, this time across the Florida peninsula to the South Florida city of Naples, not far from where Irma had made landfall. “I went there to volunteer with Samaritan’s Purse for two days,” she says, referring to the Boone, N.C.-based Christian organization that provides humanitarian aid to people in physical need. “Things were a lot worse there than in West Palm Beach,” she reports. “A lot of trees were down, houses were flooded and people had to throw all of their belongings out onto the street.”

Meanwhile, many of the Florida merchants whom Unicus funds were distressed. “If people had no power,” Vila says, “they couldn’t function. A lot of businesses had to close down. For some merchants in the affected areas,” she adds, Unicus extended “a 90-day grace period.”

Vila’s experience with Hurricane Irma – both professionally and personally — is not an isolated one. She is among several business lenders whom deBanked interviewed about the storm and its aftermath. This article grew out of deBanked’s Florida networking event at the Gale Hotel in South Beach in late January. We went back to many of the attendees as well as to other business-funders in The Sunshine State and sought out their experiences before, during and after the powerful tempest.

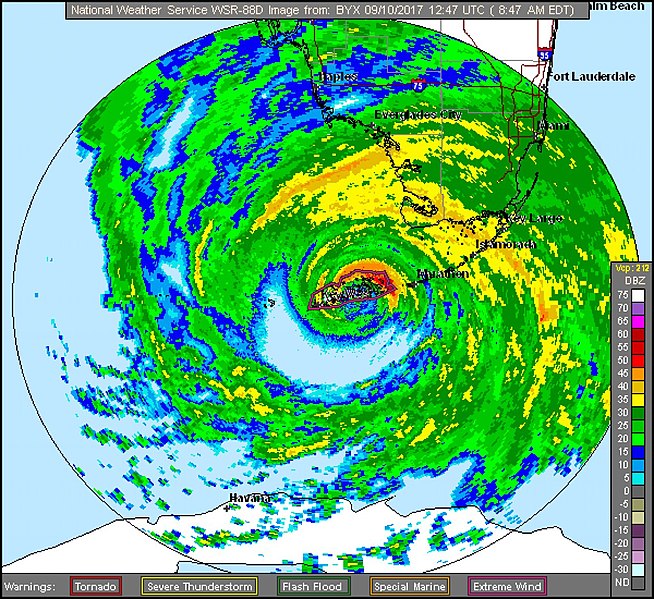

At one point, Hurricane Irma was the strongest hurricane ever recorded in the Atlantic by the National Hurricane Center. As Irma took dead aim at Florida, it packed sustained winds exceeding 157 miles per hour, earning it the designation of a Category 5 storm, the highest and most destructive. It slammed into the Florida Keys as a Category 4 hurricane, reached the Gulf of Mexico, and then came ashore a second time on Florida’s west coast at Marco Island, just south of Naples, and began traversing the state as a Category 3 hurricane, gradually losing strength. By the time Irma exited Florida, it had been downgraded to a tropical storm. According to the National Hurricane Center, Irma caused an estimated $50 billion in damage in the U.S., making it the fifth-costliest hurricane to hit the mainland.

Financiers and brokers told personal stories of working with and assisting merchants across Florida who sought to regain their lost footing and keep from going — literally — underwater. In many cases, members of the alternative business financing community said, they were simultaneously assisting troubled merchants while they themselves struggled with Irma-occasioned troubles that ranged from inconvenience to hardship.

“I was ten days without power,” says Manny Columbie, funding manager at Axiom Financial, based in South Miami. Columbie, who lives in the residential Westchester district of Miami, not far from the campus of Florida International University, says that he conducts much of his business from his home. That power loss not only constrained his ability to keep working but posed a life-or-death situation for his family: Columbie’s 90-year-old grandmother, who lives with him and his girlfriend, depends on electrical power to operate her oxygen pump.

Fortunately, he says, he had a backup generator, the use of which alternated between providing power for his grandmother’s oxygen and the family’s refrigerator. Meanwhile, his roof was leaking and there was six inches of rainwater swamping the house — the water gushing into the kitchen through the laundry room, dishwasher and even the oven.

Fortunately, he says, he had a backup generator, the use of which alternated between providing power for his grandmother’s oxygen and the family’s refrigerator. Meanwhile, his roof was leaking and there was six inches of rainwater swamping the house — the water gushing into the kitchen through the laundry room, dishwasher and even the oven.

While Columbie saw instances of tempers growing short in Miami’s September heat, he was nonetheless cheered by the way his community responded. “Neighbors were coming by to see if I needed gasoline for my generator,” Columbie says. “People were firing up food on their outside grills. There was no air-conditioning or cold showers but we cooled off by jumping in a neighbor’s pool. I saw a lot of people coming together.”

At the same time, he was doing what he could to assist merchants who did business with Axiom. Only one – a retail clothing store in Miami – was permanently shuttered. One of his clients, Oscar Pratt, owner of Odessy Party Supplies in Miami Gardens, was grateful for a moratorium on daily payments.

“We’re in the business of selling party accessories for events from births to funerals and everything in-between,” Pratt says. “Baby showers, christenings, birthdays, quinceaneras, ‘Sweet Sixteens,’ graduations, weddings, and all kinds of themed parties like Halloween,” he says. “We sell plates and cups, candy bags, cake-toppers, small favors, pinatas…”

Pratt said he’d called his funders ahead of the storm and “requested some leeway” from payments. Once the storm hit – and for two weeks afterward while there was no electricity – the party-supply business was pretty much on hold. “We had a few days without electricity or phone,” he says. “We couldn’t open the doors and do business because we use computer-generated receipts. Our customer base was down to just about nothing. Without electricity, people weren’t working and they weren’t having parties.”

Following the two-week grace period, Pratt says that his funders, which included QuarterSpot, granted a second two-week period of leniency in which Odessy was allowed to make reduced payments. “It was very difficult,” he says. “There was no help from FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) or from our insurance company since we’re on high ground and there were no physical damages, just the electricity.”

He reckoned that Odessy, which boasts annual revenues of $1.2 million, was deprived of roughly $50,000-$60,000 in sales because of Irma. Pratt reports that if his lenders had “played hardball” and demanded that he make his payments, he could have stayed in business thanks to “cash on hand” but it wouldn’t have been easy.

Meantime, his lenders’ forbearance was soon rewarded. By October, business was back to normal and he resumed making payments in full. “As soon as the lights went on,” Pratt says, “the parties started again.”

Similarly, says Paul Boxer, chief marketing officer at Quicksilver Capital in Brooklyn, the ultimate impact of Hurricane Irma on his firm’s funding business was to build trust and cement relationships with clients in South Florida. “We had a full team on board to answer the large number of calls coming in and to assist our merchants with any questions they had,” he says.

Many affected merchants, Boxer reports, were forced to evacuate ahead of the storm. When they returned, it was common for them to discover that their shops and stores sustained flooding damage from the heavy rains and a storm surge. Roofs were blown-off and structures were battered by 100-plus mile-an-hour winds, falling trees, and whipped-up debris. Even businesses that suffered little damage were paralyzed by the loss of electricity, impassable roads, and the absence of customers.

Many affected merchants, Boxer reports, were forced to evacuate ahead of the storm. When they returned, it was common for them to discover that their shops and stores sustained flooding damage from the heavy rains and a storm surge. Roofs were blown-off and structures were battered by 100-plus mile-an-hour winds, falling trees, and whipped-up debris. Even businesses that suffered little damage were paralyzed by the loss of electricity, impassable roads, and the absence of customers.

“Some were down for a few days,” Boxer reports. “Some were down a month to two months. We kept in touch. We were really on top of things with our merchants and asking them what they needed. We even fielded general safety questions and directed them on whom to call with insurance questions and other related business questions. It was good business,” he adds, “because it showed you cared. We were looking to do the right thing by our merchants and they appreciated it.”

Quicksilver typically offered merchants a two-to-three week “reprieve” on payments, Boxer says. For those businesses and entreprenuers whose operations were “completely out of commission” and needed more time, he says, the company suspended payments for as long as two months.

In the end, Quicksilver’s policy of forbearance reaped dividends. It not only built up good will with its customer base but also with the Independent Sales Organizations (ISOs) who’d brokered many of the firm’s Florida deals. “We helped grow that relationship,” Boxer says of the merchant-ISO connection. “They (ISOs) love getting renewals. It’s been a win-win for everybody.”

Doug Rovello, senior managing partner at Fund Simple, Inc., an alternative business lender and broker in Palm Harbor, a beach town just outside Tampa, says the Tampa-St. Petersburg area was spared from severe flooding but “we did experience power outages.” Among his clients, he reports, businesses in the food industry were among the most vulnerable. “I had one restaurant that lost $200,000 in business in the month of September,” he says.

When the electricity went down, grocery stores and bodegas, restaurants, bars, pizzerias, sub shops, delis and luncheonettes suffered outsized losses. Without power, businesses in the food industry were forced to dump spoiled meat, rotting fish, unusable dishes like appetizers and other foodstuffs requiring refrigeration.

When the electricity went down, grocery stores and bodegas, restaurants, bars, pizzerias, sub shops, delis and luncheonettes suffered outsized losses. Without power, businesses in the food industry were forced to dump spoiled meat, rotting fish, unusable dishes like appetizers and other foodstuffs requiring refrigeration.

Rovello reports that the hurricane managed to bollix up the business of one top client, a leading ticket broker in the area with a reputation for obtaining “exclusive” tickets to major events such as A-list rock concerts and featured sporting contests – including the Super Bowl. “He buys tickets in advance and when one big event was canceled he got stuck with $30,000 in tickets that he had to eat,” Rovello says.

Other kinds of businesses that depend on alternative lenders and got hit hard from the loss of power, Rovello observes, were medical clinics, doctors’ offices, pain-management centers, and assisted-living quarters – particularly those south of Sarasota. A number of golf courses also closed down for a couple of weeks, Rovello notes, further impairing the tourism and entertainment economy. “They were not allowed to move any of the damage that was done – poles, trees, et cetera until FEMA got there,” he says.

For some 30 days following Irma’s arrival, Rovello reports that he asked clients to make modest payments – perhaps $100 instead of a $750 monthly payment — “to keep their accounts active.” He also used his connections with FEMA adjusters and interceded with funders on behalf of clients– and even businesses that were not clients – who found themselves in arrears.

While many Floridians were seeking higher ground or hightailing it out of state, Jay Bhatt, who is a senior vice president of marketing at Breakout Capital in McLean, Va., was catching one of the last Jet Blue flights into Orlando to help out his aging parents. They are now in their late 60s and 70s, he reports, and living in a retirement community in Polk County, about ten miles south of Disney World.

Irma was still a Category 1 hurricane with 100 mph winds when it hit Orlando. The electrical grid went down, but Bhatt was able to purchase a generator – the kind designed specifically to provide electricity for oxygen respirators — from Home Depot. During his stay, Bhatt made several car trips in search of fuel, each of which took him probably 35-40 minutes. “We also leveraged some of the neighbors’ sockets,” he says, “but they were so small that the wattage only allowed for the operation of the fridge and a fan.”

Electricity was restored after four or five days. “The fact that it was a retirement community might have been why we got power back so soon while it took two or three weeks for many others,” he reckons.

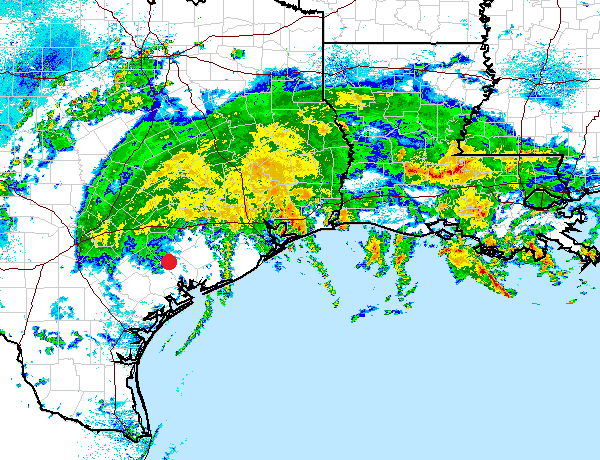

While Bhatt’s attention was focused on his parents, his employer – which had just offered a blanket hold on payments to its merchant accounts in 11 Texas counties that had been simultaneously inundated and walloped by Hurricane Harvey – now faced the challenge of responding to the second hurricane in two weeks. With Irma, Breakout chose to deal with its customers individually. “We didn’t do an immediate blanket response” as in Texas, Bhatt says, adding: “We were able to contact each one and we only wrote off one small business.”

While Bhatt’s attention was focused on his parents, his employer – which had just offered a blanket hold on payments to its merchant accounts in 11 Texas counties that had been simultaneously inundated and walloped by Hurricane Harvey – now faced the challenge of responding to the second hurricane in two weeks. With Irma, Breakout chose to deal with its customers individually. “We didn’t do an immediate blanket response” as in Texas, Bhatt says, adding: “We were able to contact each one and we only wrote off one small business.”

Rakem Lampkin, senior customer service representative at Pearl Capital, a New York-based alternative funder, says that his firm funds “roughly 175” businesses in South Florida. In addition to those establishments already mentioned as economically reeling because of Irma, such as restaurants, he cited “car dealerships, automotive repair shops and tech companies” as among the hardest hit, especially from the lack of electricity.

Lampkin also noted that many of Pearl’s merchants felt Irma’s wrath when colleges and state schools closed their doors. “Everything from transportation, lunches, sports equipment, even mom-and-pop florists” were slammed, he says, adding: “When the schools shut down, our payments slowed down.”

Pearl provided preferential treatment to merchants on the coast who were granted “a hold on debit payments,” Lampkin says. Even for coastal businesses that remained “structurally sound,” the business owners’ and employees’ “homes were affected, which kept them from getting to work,” he says.

As for businesses situated inland, “We were still sympathetic,” Lampkin says, but after an initial five-day grace-period their discounts were in the range of 66%-75% “so that we could focus our resources toward the people on the coast.”

To monitor the situation from New York, Lampkin says, the company was able to rely on accounts in the local news media, Google Maps, and other Internet sources. “We evaluated the situation case-by-case and week-by-week,” he says.

Jennifer Legg, a co-owner of Rochelle’s Jewelry & Watch Repair at the Indian River Mall in Vero Beach, is a Pearl-funded merchant who says she shut down the family-run business “for six or seven days” after Irma while the electricity went out. “Trees were down and a lot of people lost food and trailers, but we were not impacted as much as we were supposed to be,” she remarked.

Most of the shop’s business consists of customers stopping in for a new battery or a watch-band. Once they’re in the store, there’s a chance that they’ll purchase something else. But Irma put the kibosh on mall traffic. “A lot of people left the state, so that hurt business,” Legg says.

The store – which records annual sales of about $200,000 — lost probably $10,000 in revenue because of Irma. “It was very hard for that month of September,” Legg says. “Even after the doors opened, it was dead. No money came in for about two weeks.”

Fortunately, though, her capital source “did not take money out for a week,” she says. “If they’d kept taking it out,” she added, “we would have defaulted.”