Marketplace Lending

SoFi is Now a Fannie Mae Seller, Servicer

May 4, 2016

SoFi clocked in another milestone in mortgage lending by becoming an approved Fannie Mae seller and servicer.

SoFi Lending Corp, the company’s wholly owned subsidiary can, as a seller, sell mortgage loans to Fannie Mae and service loans on behalf of the Federal National Mortgage Association.

“While we launched our mortgage business focused on larger ‘jumbo’ loans, the certainty and efficiency offered by Fannie Mae will enable us to serve more members by expanding geographically and into smaller loan amounts,” said Michael Tannenbaum, VP of Mortgage at SoFi in a press release. “Sixty-five percent of SoFi’s purchase customers are first-time homeowners who have what we call a ‘millennial mindset.”

In March this year, the company was laying down the works to start a real estate trust to buy mortgages sold by the lender. According to Bloomberg, some of SoFi’s borrowers seek mortgages that are too big to be funded through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

In the crowded online lending space, where customer acquisition is key, companies scramble to lock in borrowers early to keep lending to them through different life stages from student loans to auto loans to mortgages. SoFi uses the free cash flow method for mortgages, a deviation from the industry standard of debt-to-income ratio.

“There isn’t a banker out there that doesn’t look at me and shake his head and say, ‘You don’t know what you’re doing, but we’re doing it,” Cagney told Bloomberg. SoFi plans to sell $3 billion in mortgages this year.

Is The Marketplace Lending Apocalypse Upon Us?

May 3, 2016

Days after rumors leaked that Prosper Marketplace had planned to lay off staff, the WSJ is now reporting that the company is indeed eliminating 171 jobs, closing their Utah office and letting go of their chief risk officer. CEO Aaron Vermut’s salary has also been cut to zero.

The timing for the industry they’re a part of couldn’t be worse. OnDeck’s stock closed down 34% today after Q1 losses and revised projections took analysts by surprise. The source of the pain? OnDeck’s “Marketplace.” The institutional investors typically willing to pay a high premium for loans disappeared, according to OnDeck executives on the earnings call.

Unsurprisingly, Prosper’s “Marketplace” has historically relied on institutional buyers for their loans too, as much as 92% of all loans on the platform in fact. Prosper’s roots as a peer-to-peer lender don’t make it an ideal candidate to just shift loans to their balance sheet like OnDeck, which could make the changing capital markets landscape even more painful for them.

Two months ago, Prosper raised the interest rates they charge, citing a “turbulent market environment.” And just weeks ago, Citigroup announced that they would no longer buy loans from Prosper to package into bonds. Now, signs of stress are finally starting to show.

And then there’s Lending Club, a “marketplace” rival to both Prosper and OnDeck, who experienced a 10% decline in its stock price today. The company’s model is under fire through a class action lawsuit that alleges among other things that they along with WebBank are Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organizations. Lending Club plans to release their Q1 earnings on May 9th.

And it’s not just the capital markets and lawsuits shaking up the landscape. Half a dozen trade associations have been formed over the last few months to quell some of the negative rhetoric surrounding online lending in Washington and to educate policymakers on the positive aspects of these services.

In the Illinois State Senate for example, a pending bill has the potential to outlaw all nonbank business lending altogether.

Some of those that broker business loans have already fallen on hard times due to things like the cost of leads skyrocketing.

“Anybody can fund deals – the talent lies in collecting the money back at a profitable level,” said Capify CEO David Goldin in deBanked’s most recent magazine. “There’s going to be a shakeout. I can feel it.”

The early signs of that prediction may finally be starting to unfold.

After the Lendit Conference last month, I speculated that marketplace lending euphoria ended because the relationship between investors and platforms was in some ways based on lust, not love. The breakup is now starting to manifest itself in the form of missed earnings and layoffs.

Is the apocalypse upon us? Probably not yet, but these foreshocks are a good sign that we’ll soon be separating the wheat from the chaff.

Make sure to wear your hazmat gear as you enter the marketplace.

OnDeck Disappoints: “Marketplace” in Jeopardy?

May 3, 2016

OnDeck finally bombed an earnings report and marketplace lending (at least their marketplace anyway) is being seriously questioned. The company is now predicting a full-year adjusted EBITDA loss of between $41 million and $49 million, down from the projection they made just three months ago of full-year positive EBITDA of $10 million to $14 million. They had a GAAP net loss in Q1 of $12.6 million.

Any positive details were disregarded by analysts who hammered away at the shifting dynamic of the OnDeck Marketplace. The premium earned on selling off loans to major investors through this channel shrank to a measly 5.7% Gain on Sale Rate during the first quarter. Bank of America’s Nat Schindler pointed out on the call that back when OnDeck was getting a 9% Gain on Sale Rate, that they believed even that number to be undervalued, but that they had said it was worth selling them at a discount to “seed the marketplace.” With the margins now compressed to a point where “seeding the marketplace” is no longer a rational excuse, he wondered why they still sold $123 million worth. “Why not just keep it all? What would happen if you just stopped the marketplace?” he asked.

Stop the marketplace

Stopping the marketplace quickly became the underlying theme of the Q&A session. Previously, 35-45% of their term loans were sold off through Marketplace but they now predict that only 15%-25% will be sold through it in 2016.

David Scharf with JMP Securities asked if and when the company could ever break even assuming there was no marketplace.

Vasu Govil with Morgan Stanley asked “if the risk premiums were to continue to rise, at what point does marketplace funding go to zero? At what point do you decide that it’s not worth doing it and that you want to keep all the risk on the balance sheet?”

OnDeck CFO Howard Katzenberg explained the decreasing margins as a retreat from one type of buyer. “Our marketplace buyers fall into two counts,” he said. “The first is those that buy and want to hold ’til maturity and the other segment buys with the plan on securitizing the loans and selling off the residual position of the portfolio. Given the inherent leverage in the securitization transactions, those buyers historically have been willing to pay higher premiums versus the kind of the more traditional hold ’til maturity investors.”

The appetite from those that plan to securitize the loans has dropped off, the ones that are typically willing to pay more.

Losses today instead of income

OnDeck did book more loans on their balance sheet than they had expected and as a result GAAP rules require them to book a provision expense for them. “So as our loan book grows, we will have a mismatch of the provision expense upfront versus earning interest income over the lifetime of the loan,” Katzenberg said. “Moreover, when we sell a loan through marketplace, we book a gain on sale upfront, which had the affect of accelerating the recognition of income.”

Translation: Booking a loan on balance sheet means recording a loss today while selling a loan through marketplace means booking income today. The first might be more profitable over time but transitioning from marketplace to balance sheet makes the books look worse in the short term.

Originations down

Actual originations grew by 37% year-over-year, missing the 40-50% range projected. OnDeck CEO Noah Breslow was unapologetic about that. “We’re not going to do anything unnatural because of those growth numbers,” he argued. “If we conclude that growing at a slower rate is best for our business then we will grow slower.”

The stock was down 3.82% on the day prior to the earnings release but plunged by nearly 30% in after hours trading.

Online Small Business Lending Task Force Initiated by the ETA

April 30, 2016 The Electronic Transactions Association (ETA) is now advocating on behalf of online small business lenders.

The Electronic Transactions Association (ETA) is now advocating on behalf of online small business lenders.

Though you might not have suspected it last week at Transact16, the ETA very much plans to involve themselves in the affairs of marketplace lending. That might not have been obvious from a Bloomberg article that reported that OnDeck, Kabbage and PayPal were forming a splinter organization as an “extension” of the ETA known as the Online Small Business Lending Task Force. Referred to as a new initiative in the announcement, the group’s mission is described as striving to “prevent hasty or overly restrictive regulations.”

But the group’s named lobbyist, Scott Talbott, is also the ETA’s lobbyist. And the three lenders named, were already members of the ETA. When Talbott was asked by deBanked to clarify the relationship between the “task force” and the ETA, he said that the two weren’t separate. The “ETA organized its members to lobby on the issue. It’s what we do every day,” he wrote.

The “task force” merely highlights members in the trade group that share a common interest.

Formed in 1990 and comprising of over 550 companies across 7 countries, the ETA has served the payments industry well. OnDeck, Kabbage and PayPal therefore find themselves in good company and led by advocates with well-established government relationships.

Along with the ETA, the online small business lending industry has found support from the Marketplace Lending Association, the Small Business Finance Association, the Commercial Finance Coalition and the Coalition for Responsible Business Finance.

Why Does Lending Club Set The Interest Rates If It’s A “Marketplace”?

April 29, 2016 A new user on the LendAcademy forum asked a good question.

A new user on the LendAcademy forum asked a good question.

“If Lending Club is merely creating a marketplace for borrowers and investors, why does LC set the price? Why not let them determine it independently? The external credit models are fundamentally about finding loans with the highest expected return relative to their risk.”

Here are some of the summarized responses that were given:

– Individual investors are not as able to price risk on their own

– It would be inefficient, much more time would be needed to investigate each loan

– Prosper started out doing it this way and the results were poor

– Lending Club doesn’t disclose all the data points to investors for proprietary reasons and to avoid releasing information that could lead to borrower discrimination, i.e. violations of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) and Consumer Credit Protection Act (CCPA). It’s better to have a third party manage these legal risks.

Today, many investors use automated programs like LendingRobot to do their investing for them, which means the hassle of trying to price a loan in a dutch auction with limited information would likely become an obstacle in the marketplace. It would also become a race to the bottom. Underpricing risk would be great for borrowers because they’d benefit from very low interest rates but it would be a disaster for investors that would likely experience losses as a result. If investors were all institutional and accredited, then maybe that would be fine. But since Lending Club has a substantial amount of unaccredited investors, the kind legally presumed to be unsophisticated, putting the onus of pricing risk on their shoulders would quickly lead to the collapse of the system entirely.

Lending Club might not be a marketplace in the purest sense, but given the legal complexities and investor/borrower protection considerations, it comes pretty close.

You can read the original thread on the LendAcademy forum here.

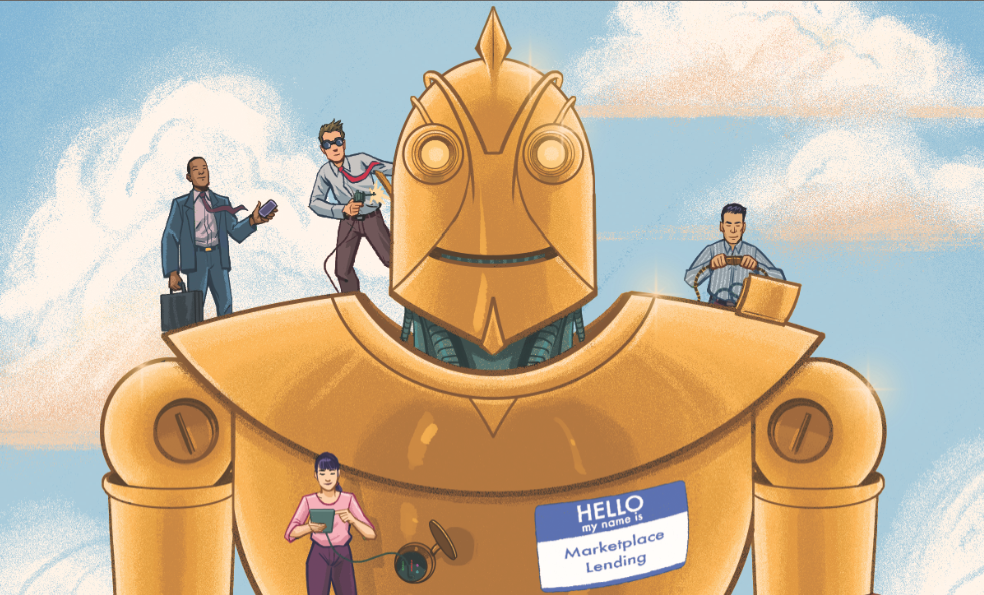

Stairway to Heaven: Can Alternative Finance Keep Making Dreams Come True?

April 28, 2016

The alternative small-business finance industry has exploded into a $10 billion business and may not stop growing until it reaches $50 billion or even $100 billion in annual financing, depending upon who’s making the projection. Along the way, it’s provided a vehicle for ambitious, hard-working and talented entrepreneurs to lift themselves to affluence.

Consider the saga of William Ramos, whose persistence as a cold caller helped him overcome homelessness and earn the cash to buy a Ferrari. Then there’s the journey of Jared Weitz, once a 20 something plumber and now CEO of a company with more than $100 million a year in deal flow.

Their careers are only the beginning of the success stories. Jared Feldman and Dan Smith, for example, were in their 20s when they started an alt finance company at the height of the financial crisis. They went on to sell part of their firm to Palladium Equity Partners after placing more than $400 million in lifetime deals.

Their careers are only the beginning of the success stories. Jared Feldman and Dan Smith, for example, were in their 20s when they started an alt finance company at the height of the financial crisis. They went on to sell part of their firm to Palladium Equity Partners after placing more than $400 million in lifetime deals.

The industry’s top salespeople can even breathe new life into seemingly dead leads. Take the case of Juan Monegro, who was in his 20s when he left his job in Verizon customer service and began pounding the phones to promote merchant cash advances. Working at first with stale leads, Monegro was soon placing $47 million in advances annually.

The industry’s top salespeople can even breathe new life into seemingly dead leads. Take the case of Juan Monegro, who was in his 20s when he left his job in Verizon customer service and began pounding the phones to promote merchant cash advances. Working at first with stale leads, Monegro was soon placing $47 million in advances annually.

Alternative funding can provide a second chance, too. When Isaac Stern’s bakery went out of business, he took a job telemarketing merchant cash advances and went on to launch a firm that now places more than $1 billion in funding annually.

All of those industry players are leaving their marks on a business that got its start at the dawn of the new century. Long-time participants in the market credit Barbara Johnson with hatching the idea of the merchant cash advance in 1998 when she needed to raise capital for a daycare center. She and her husband, Gary Johnson, started the company that became CAN Capital. The firm also reportedly developed the first platform to split credit card receipts between merchants and funders.

BIRTH OF AN INDUSTRY

Competitors soon followed the trail those pioneers blazed, and the industry began growing prodigiously. “There was a ton of credit out there for people who wanted to get into the business,” recalled David Goldin, who’s CEO of Capify and serves as president of the Small Business Finance Association, one of the industry’s trade groups.

Competitors soon followed the trail those pioneers blazed, and the industry began growing prodigiously. “There was a ton of credit out there for people who wanted to get into the business,” recalled David Goldin, who’s CEO of Capify and serves as president of the Small Business Finance Association, one of the industry’s trade groups.

Many of the early entrants came from the world of finance or from the credit card processing business, said Stephen Sheinbaum, founder of Bizfi. Virtually all of the early business came from splitting card receipts, a practice that now accounts for just 10 percent of volume, he noted.

At first, brokers, funders and their channel partners spent a lot of time explaining advances to merchants who had never heard of them, Goldin said. Competition wasn’t that tough because of the uncrowded “greenfield” nature of the business, industry veterans agreed.

Some of the initial funding came from the funders’ own pockets or from the savings accounts of their elderly uncles. “I’ve met more than a few who had $2 million to $5 million worth of loans from friends and family in order to fund the advances to the merchants,” observed Joel Magerman, CEO of Bryant Park Capital, which places capital in the industry. “It was a small, entrepreneurial effort,” Andrea Petro, executive vice president and division manager of lender finance for Wells Fargo Capital Finance, said of the early days. “A number of these companies started with maybe $100,000 that they would experiment with. They would make 10 loans of $10,000 and collect them in 90 days.”

That business model was working, but merchant cash advances suffered from a bad reputation in the early days, Goldin said. Some players were charging hefty fees and pushing merchants into financial jeopardy by providing more funding than they could pay back comfortably. The public even took a dim view of reputable funders because most consumers didn’t understand that the risk of offering advances justified charging more for them than other types of financing, according to Goldin.

Then the dam broke. The economy crashed as the Great Recession pushed much of the world to the brink of financial disaster. “Everybody lost their credit line and default rates spiked,” noted Isaac Stern, CEO of Fundry, Yellowstone Capital and Green Capital. “There was almost nobody left in the business.”

RAVAGED BY RECESSION

Perhaps 80 percent of the nation’s alternative funding companies went out of business in the downturn, said Magerman. Those firms probably represented about 50 percent of the alternative funding industry’s dollar volume, he added. “There was a culling of the herd,” he said of the companies that failed.

Life became tough for the survivors, too. Among companies that stayed afloat, credit losses typically tripled, according to Petro. That’s severe but much better than companies that failed because their credit losses quintupled, she said.

Who kept the doors open? The firms that survived tended to share some characteristics, said Robert Cook, a partner at Hudson Cook LLP, a law office that specializes in alternative funding. “Some of the companies were self-funding at that time,” he said of those days. “Some had lines of credit that were established prior to the recession, and because their business stayed healthy they were able to retain those lines of credit.”

The survivors also understood risk and had strong, automated reporting systems to track daily repayment, Petro said. For the most part, those companies emerged stronger, wiser and more prosperous when the crisis wound down, she noted. “The legacy of the Great Recession was that survivors became even more knowledgeable through what I would call that ‘high-stress testing period of losses,’” she said.

ROAD TO RECOVERY

The survivors of the recession were ready to capitalize on the convergence of several factors favorable to the industry in about 2009. Taking advantages of those changes in the industry helped form a perfect storm of industry growth as the recession was ending.

The survivors of the recession were ready to capitalize on the convergence of several factors favorable to the industry in about 2009. Taking advantages of those changes in the industry helped form a perfect storm of industry growth as the recession was ending.

They included making good use of the quick churn that characterizes the merchant cash advance business, Petro noted. The industry’s better operators had been able to amass voluminous data on the industry because of its short cycles. While a provider of auto loans might have to wait five years to study company results, she said, alternative funders could compile intelligence from four advances within the space of a year.

That data found a home in the industry around the time the recession was ending because funders were beginning to purchase or develop the algorithms that are continuing to increase the automation of the underwriting process, said Jared Weitz, CEO of United Capital Source LLC. As early as 2006, OnDeck became one of the first to rely on digital underwriting, and the practice became mainstream by 2009 or so, he said.

Just as the technology was becoming widespread, capital began returning to the market. Wealthy investors were pulling their funds out of real estate and needed somewhere to invest it, accounting for part of the influx of capital, Weitz said.

At the same time, Wall Street began to take notice of the industry as a place to position capital for growth, and companies that had been focused on consumer lending came to see alternative finance as a good investment, Cook said.

For a long while, banks had shied away from the market because the individual deals seem small to them. A merchant cash advance offers funders a hundredth of the size and profits of a bank’s typical small-business loan but requires a tenth of the underwriting effort, said David O’Connell, a senior analyst on Aite Group’s Wholesale Banking team.

The prospect of providing funds became even less attractive for banks. The recession had spawned the Dodd-Frank Financial Regulatory Reform Bill and Basel III, which had the unintended effect of keeping banks out of the market by barring them from endeavors where they’re inexperienced, Magerman said. With most banks more distant from the business than ever, brokers and funders can keep the industry to themselves, sources acknowledged.

At about the same time, the SBFA succeeded in burnishing the industry’s image by explaining the economic realities to the press, in Goldin’s view.The idea that higher risk requires bigger fees was beginning to sink in to the public’s psyche, he maintained.

Meanwhile, loans started to join merchant cash advances in the product mix. Many players began to offer loans after they received California finance lenders licenses, Cook recalled. They had obtained the licenses to ward off class-action lawsuits, he said and were switching from sharing card receipts to scheduled direct debits of merchants’ bank accounts.

As those advantages – including algorithms, ready cash, a better image and the option of offering loans – became apparent, responsible funders used them to help change the face of the industry. They began to make deals with more credit-worthy merchants by offering lower fees, more time to repay and improved customer service. “The recession wound up differentiating us in the best possible way,” Bizfi’s Sheinbaum said of the changes.

His company found more-upscale customers by concentrating on industries that weren’t hit too hard by the recession. “With real estate crashing, people were not refurbishing their homes or putting in new flooring,” he noted.

Today, the booming alternative finance industry is engendering success stories and attracting the nation’s attention. The increased awareness is prompting more companies to wade into the fray, and could bring some change.

WHAT LIES AHEAD

One variety of change that might lie ahead could come with the purchase of a major funding company by a big bank in the next couple of years, Bryant Park Capital’s Magerman predicted. A bank could sidestep regulation, he suggested, by maintaining that the credit card business and small business loans made through bank branches had provided the banks with the experience necessary to succeed.

Smaller players are paying attention to the industry, too, with varying degrees of success. Predictably, some of the new players are operating too aggressively and could find themselves headed for a fall. “Anybody can fund deals – the talent lies in collecting the money back at a profitable level,” said Capify’s Goldin. “There’s going to be a shakeout. I can feel it.”

Smaller players are paying attention to the industry, too, with varying degrees of success. Predictably, some of the new players are operating too aggressively and could find themselves headed for a fall. “Anybody can fund deals – the talent lies in collecting the money back at a profitable level,” said Capify’s Goldin. “There’s going to be a shakeout. I can feel it.”

Some of today’s alternative lenders don’t have the skill and technology to ward off bad deals and could thus find themselves in trouble if recession strikes, warned Aite Group’s O’Connell. “Let’s be careful of falling into the trap of ‘This time is different,’” he said. “I see a lot of sub-prime debt there.”

Don’t expect miracles, cautioned Petro. “I believe there will be another recession, and I believe that there will be a winnowing of (alternative finance) businesses,” she said. “There will be far fewer after the next recession than exist today.”

A recession would spell trouble, Magerman agreed, even though demand for loans and advances would increase in an atmosphere of financial hardship. Asked about industry optimists who view the business as nearly recession-proof, he didn’t hold back. “Don’t believe them,” he warned. “Just because somebody needs capital doesn’t mean they should get capital.”

Further complicating matters, increased regulatory scrutiny could be lurking just beyond the horizon, Petro predicted. She provided histories of what regulation has done to other industries as an indication of the differing outcomes of regulation – one good, one debatable and one bad.

Good: The timeshare business benefitted from regulation because the rules boosted the public’s trust.

Debatable: The cost of complying with regulations changed the rent-to-own business from an entrepreneurial endeavor to an environment where only big corporations could prosper.

Bad: Regulation appears likely to alter the payday lending business drastically and could even bring it to an end, she said.

Still, regulation’s good side seems likely to prevail in the alternative finance business, eliminating the players who charge high fees or collect bloated commissions, according to Weitz. “I think it could only benefit the industry,” he said. “It’ll knock out the bad guys.”

Lending Club Looks to Do First Major Securitization Deal

April 26, 2016

As marketplace lenders look to reduce their dependence on traditional capital sources, Lending Club appears to be ready to finally give in and do a securitization.

Lending Club is reportedly in talks with Goldman Sachs and Jefferies Group to put together its first big bond offering, according to the WSJ. The news is significant because the company has previously shunned them.

Earlier this year, Lending Club CEO Renaud Laplanche told the Financial Times, “We are showing that we can scale without the securitization market.” That was after saying they weren’t “willing to take more risk to do a securitization than we would through the normal operation of the platform.”

Since then, the market and the mood has changed. Citigroup for example, announced that they would stop securitizing loans for Lending Club rival Prosper Marketplace only two weeks ago due to looming fears of increasing losses. Prosper is also reported to be talking to Goldman Sachs about future securitizations.

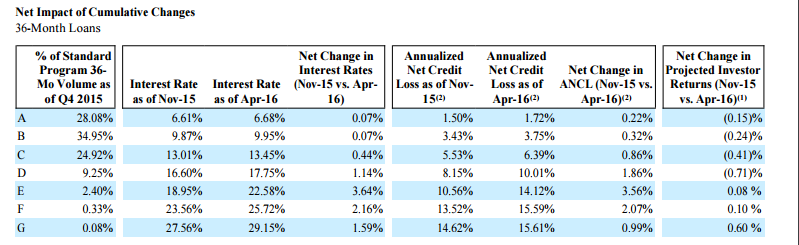

Signs of Slowdown? Lending Club Increases Rates, Adjusts Forecast

April 21, 2016 Should online lenders prepare for a downturn already? Lending Club has a cue.

Should online lenders prepare for a downturn already? Lending Club has a cue.

In a SEC filing on Thursday (April 21) the marketplace lender notified the bureau that it will increase interest rates by 23 basis points and also updated its loss projections.

The hike in rates were concentrated in Grades D – G, identified by the company as underperforming pockets of loans representing 5 percent of the loan volume.

“The population eliminated from the credit policy was mainly characterized by high indebtedness, an increased propensity to accumulate debt and lower credit scores,” the filing said.

The rate hike comes as online lenders look to securitize debt and continue to pursue permanent sources of capital. The industry’s meteoric rise can be attributed to its lenient lending standards but as competition increases the lenders still look to bring more borrowers into the fold. Publicly listed companies like Lending Club have to walk the tightrope between growth and risk.

“Over the past few months the Lending Club marketplace has made a number of proactive changes to reflect the general evolution of interest rates and prepare for a potential slowdown in the economy,” Lending Club said in its filing.

And as alternative lending companies look to disrupt traditional models of lending, several of them are hiring top banking talent for the task.

Lending Club also announced that it hired former McKinsey chief of digital banking, Sameer Gulati as its chief operating officer and promoted chief marketing officer Scott Sanborn to president.

In their new roles, Gulati will head operations and corporate strategy and Sanborn will oversee the company’s product lines (personal loans, small business and patient and education financing) as well as marketing and product development.