Business Lending

Kabbage Extends Credit Lines to $250,000

February 2, 2018 Kabbage, the online business lender, is now offering credit lines of up to $250,000, which it says is the largest credit line available from any online lender and will allow the company to expand its customer base to serve larger companies.

Kabbage, the online business lender, is now offering credit lines of up to $250,000, which it says is the largest credit line available from any online lender and will allow the company to expand its customer base to serve larger companies.

“Increasing our lines of credit to $250,000 significantly enhances our ability to solve financial hurdles for larger and more specialized businesses,” said Bob Sharpe, COO of Kabbage.

The company finished 2017 having crossed the $4 billion threshold for loans issued to more than 130,000 small businesses. And its Chief Revenue Officer, Victoria Treyger, told deBanked back in December that loans were getting larger.

“Our lines of credit and amounts taken continue to increase as we begin serving more and larger small businesses,” she said. “We see great momentum across all industries in all 50 U.S. states.”

Back in September, the Atlanta-based company received an investment of $250 million from Japanese telecommunications company, SoftBank, and the company has been thriving.

By the end of last year, it had lent a total of $4 billion since it was founded in 2009. According to American Banker, Kabbage worked with its banking partner, Salt Lake City-based Celtic Bank, to develop the larger line of credit.

Kathryn Petralia, Kabbage’s president and co-founder, is excited about this new development.

“[This] helps us close the capital gap that businesses encounter today,” she told American Banker. “It allows us to better the customers we have who qualify for more credit.

StreetShares Completes $23 Million Investment, Sticking With Their Plan

January 30, 2018 StreetShares, the small business lender focused on making loans to veteran-owned businesses, completed a $23 million series B funding round last week. The round was led by a $20 million investment from Rotunda Capital Partners, LLC, with an additional $3 million from existing investors, including Stoney Lonesome Group.

StreetShares, the small business lender focused on making loans to veteran-owned businesses, completed a $23 million series B funding round last week. The round was led by a $20 million investment from Rotunda Capital Partners, LLC, with an additional $3 million from existing investors, including Stoney Lonesome Group.

According to the company’s June 30th 2017 fiscal year-end financial statements, it only made 751 loans in a 12-month period. Other companies may make thousands in the same period.

However, this is because StreetShares approach to earning is different than most online lending companies. Rather than relying primarily on increasing the volume of loans to generate revenue, they also earn by co-investing in loans, according to Mark Rockefeller, CEO and Co-founder of the three and a half year-old Reston, VA-based company.

In an email, Rockefeller, who is himself a veteran, also conveyed that they have sought out VC equity investors who are patient and want them to issue high quality loans.

According to StreetShares’ June 30th fiscal year-end financial statements, the company’s revenues were $2,168,067 and its losses were $6,193,154. While this might be of concern to other companies, this isn’t alarming to Rockefeller. It’s part of the plan.

“Our patient approach means we’re not going to be profitable for a couple more years. But it also means we’ll still be here in 50 years.”

deBanked Connect – Miami (Recap)

January 30, 2018Thank you to everyone who attended our cocktail networking event in South Beach last week. It was a great opportunity for funders, lenders, brokers and others in the industry to connect with each other (many for the first time ever). Thank you again to Everest Business Funding, National Funding, Knight Capital Funding, NISO, Grand Capital Funding, and Venture Credit Solutions for sponsoring.

Below is a sample of our photos from the evening. If you attach any of your own on social media, please use #debankedconnect so that we can find them.

READY FOR AN EVEN BIGGER & MORE COMPREHENSIVE DEBANKED INDUSTRY EVENT?

BROKER FAIR IS COMING MAY 14, 2018

TO BROOKLYN, NY

JOIN FUNDERS, LENDERS AND BROKERS FOR THE INAUGURAL CONFERENCE

LEARN MORE HERE

CHECK OUT THE BIG NAMES SPONSORING BROKER FAIR 2018

BFS Capital’s Marrache on Canadian Small Business Landscape

January 28, 2018

It’s been about five months since Michael Marrache took the reins as CEO of BFS Capital. He spoke with us then about the company’s algorithmic solutions, ISO relationships and product pipeline. He recently took some time to talk with deBanked about the key themes in the Canadian market in 2018 – from minimum wage, to the impact of US tax reform on the Canadian economy, to ISO opportunities — and BFS Capital’s role there.

deBanked: When did BFS Capital begin operating in Canada?

Marrache: BFS Capital funded its first loan in Canada in 2012. Traditionally, we have approached Canada’s market via our partner channel, both US and Canada based. We plan on increasing that effort in 2018.

deBanked: Is Canada a market that BFS Capital recognizes as growing?

Marrache: Canada is a growing market for BFS Capital, though our non-US markets, including Canada and the UK, currently represent less than 20% of our global $300 million in financings. We see significant upside in both Canada and the UK in the next 12 months.

deBanked: What are the themes as you see them for Canadian small businesses and BFS Capital in 2018?

Marrache: There might be more insecurity among Canadian small businesses this year. The 2018 minimum wage increase to $14 an hour in Ontario, expected to rise again in 2019, for example, might cause some small businesses to have to cut hours or reduce staff to make up for the expense. They may have to raise their prices, which could impact demand.

Additionally, recent policy and legislative changes in the US could also impact Canada. For example, tax reform in the US, specifically a reduction in the US corporate rate, will put the US on par with Canada in terms of tax rates and similar burdens. At the same time, US regulations are being reduced while Canada’s appear to be increasing. All of this is part of the current US government’s initiative to drive domestic business growth and we are not sure how it will affect Canada’s economy, business confidence and consumer spending.

The Canadian dollar is also forecast to remain weak and might continue to fall for a while longer. With US tax reform potentially boosting the economy here, the US Fed is likely to raise interest rates, which might reduce demand for the Canadian dollar. The CAN$ could further slide if Bank of Canada cuts rates again. [Scotiabank]

At the core, however, Canada has 1.1 million small businesses. Not a small number. There were more than 350,000 small businesses created in Canada in 2016 and 42% of job creation in the country in the past decade stemmed from firms with fewer than 100 employees (CIBC Capital Markets). These businesses need working capital for a variety of needs related to their everyday business and, importantly for where we fit in, it has traditionally been difficult for small businesses to obtain financing from banks.

BFS Capital financing has come into the mainstream because it’s more accessible than a bank loan, less expensive than equity, and less risky than bootstrapping. Our financing solutions also require less commitment than taking on a partner or getting venture capital. Moreover, the few big banks in the market have tended to shy away from small businesses, so we have seen an opportunity with our ISO partner-base and directly, for our lending solutions.

Today small businesses in Canada can get the money in their account in just a day or two and there are a variety of products with different rates and payment options. As the market in Canada gets more competitive the rates will continue to go down.

deBanked: The last time I spoke with you, you talked about automated solutions, transparency tied to ISOs and company culture. Are these at the forefront of the Canadian business as well? Explain.

Marrache: Yes. These initiatives are embedded in the company strategy at the top. We believe speed is required but not sufficient; the company must lead with a culture of service and transparency. We are also investing in data science to improve risk profiling and process efficiencies for every partnership and every financing, including in Canada. These initiatives have been instrumental to our strengthened partnerships in the US and we expect these to benefit our Canadian partners as well.

deBanked: Can you provide any illustration of the number of Canadian merchants on the BFS Capital platform or the amount in loans or MCAs you’ve deployed in the country?

Marrache: Although at a more modest volume than our business in the US, since entering the Canadian market in 2012, BFS Capital has achieved originations growth of approximately 100 percent on a compounded annual growth basis.

New Legislation boosts SBA Oversight Over 7(a)

January 17, 2018This month, the Small Business 7(a) Lending Oversight and Reform Act of 2018 was put forth by a bipartisan team of lawmakers. If approved, the bill will increase the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) oversight authority over the 7(a) loan program, which aids small businesses and entrepreneurs as they set out to launch or grow their enterprises.

Via press release, the pending legislation was credited with “preserving” the 7(a) loan program by strengthening the SBA’s Office of Credit Risk Management by outlining in statute the responsibilities of the office and the requirements of its director, enhancing SBA’s lender oversight review process, including increasing the office’s enforcement options, requiring SBA to detail its oversight budget and perform a full risk analysis of the program annually and enhancing the organization’s “Credit Elsewhere” test.

“The 7(a) loan program has leveraged billions of dollars to help America’s small businesses thrive,” said Senate Small Business and Entrepreneurship Committee Chairman Jim Risch (R-ID) via the release. “By bolstering the SBA’s oversight office and providing the Administrator with flexibility to increase the program’s maximum lending authority in the event it would be reached, this bill will ensure the strength of the program into the future, guaranteeing that entrepreneurs will have access to the critical capital they need to build and grow their businesses.”

He continued, stating that the “bipartisan and bicameral support for this effort underscores just how important the 7(a) program, and the capital it provides, is to our nation’s small business owners.”

“The House Small Business Committee has a long tradition of working across the aisle to promote opportunity and job growth for America’s small businesses and, central to that effort, is ensuring entrepreneurs can access adequate capital to grow their operations,” said Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) in agreement.

“Since its inception, the 7(a) initiative has provided new and existing ventures with financing to grow and create jobs in local communities,” she added. “Under this legislation, SBA will have more tools to meet small businesses’ needs. I’m particularly pleased the bill includes provisions from my legislation allowing SBA to raise its 7(a) lending cap, so there’s no interruption in the flow of loans to small firms.”

Alternative Lending Set to Boost Small Business Strength in 2018

January 16, 2018 Small business lending saw a 2017 surge, according to the U.S. Small Business Credit Monthly Report from PayNet, with 11 of 18 sectors experiencing a lending increase over the past 12 months.

Small business lending saw a 2017 surge, according to the U.S. Small Business Credit Monthly Report from PayNet, with 11 of 18 sectors experiencing a lending increase over the past 12 months.

Experts believe 2018 will continue to foster a friendly environment for smaller enterprises.

“A combination of small business optimism and favorable tax changes will likely spur increased demand for small business loans in 2018,” Gerri Detweiler, education director at Nav, tells deBanked. “This, combined with personal credit scores and business credit scores at all-time highs, means 2018 should be another record year for small business lending.”

Detweiler added that big banks have begun to fine tune their incorporation of alternative data sources into underwriting decisions. She believes that those who continue to do this well are on track for a “very good year” in 2018.

Head of marketing at Fundbox, Greg Powell, also believes in the strength of alternative data as a catalyst for small business growth due to more flexible vetting processes.

“Over 60% of small businesses are looking to make a capital investment in the year 2018,” he said. “On the supply side, you have a growing wealth of options that small businesses can choose from. That for me would be a cause for a lot of optimism of starting out a new business in the year 2018.”

“What we’re seeing is a fundamental shift in the way that businesses can be underwritten,” Powell continued,” adding that Fundbox and others like it are able to reach small businesses that no one else can.

Fundbox bypasses the need for a small business owner’s personal credit score or personal guarantee by putting more focus on factors such as the value of the borrower’s previous three months worth of transaction value and a flexible benchmark of $50K or more in annual revenues.

Lending standards such as this have led to a loan application climate that is “a lot more fluid than in the past,” according to Powell.

Jersey City is Quietly Becoming a Fintech Hub

January 11, 2018 Jersey City is luring yet another innovative small business finance company to their community. This time it’s NYC-based Pearl Capital. According to NJ state records, Pearl was approved on January 9th for a total of $5.6 million over 10 years to relocate under the Grow NJ tax program to boost jobs in the area.

Jersey City is luring yet another innovative small business finance company to their community. This time it’s NYC-based Pearl Capital. According to NJ state records, Pearl was approved on January 9th for a total of $5.6 million over 10 years to relocate under the Grow NJ tax program to boost jobs in the area.

Other finance companies that have relocated to Jersey City, thanks to Grow NJ, are Yellowstone Capital, World Business Lenders, and Principis Capital. But that’s not all, companies like BlueVine and Funding Metrics have also set up operational centers there.

We do not yet know what address Pearl intends to move to.

What’s Lending Got to do With Cryptocurrency?

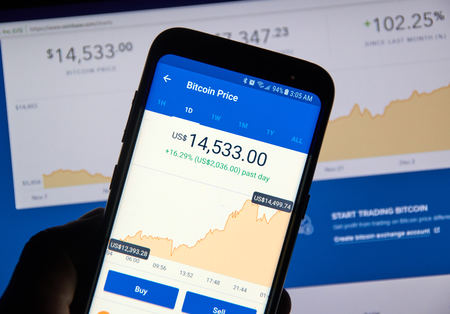

January 10, 2018 Facebook and Snapchat might be the last things that employees are being distracted by these days. Instead it’s Coinbase and Blockfolio, two cryptocurrency apps, that are quickly stealing the attention of young finance professionals. And the interest in Bitcoin, Ethereum and alt coins is causing some in the industry to wonder if the phenomenon can somehow be connected to online lending and merchant cash advance.

Facebook and Snapchat might be the last things that employees are being distracted by these days. Instead it’s Coinbase and Blockfolio, two cryptocurrency apps, that are quickly stealing the attention of young finance professionals. And the interest in Bitcoin, Ethereum and alt coins is causing some in the industry to wonder if the phenomenon can somehow be connected to online lending and merchant cash advance.

A meetup hosted by partners of Central Diligence Group (CDG) on Tuesday night in NYC, for example, was geared towards cryptocurrency enthusiasts. CDG is a merchant cash advance and business lending consulting firm. Those that attended, talked candidly about Ripple, Bitcoin, Ethereum, and the hot topic of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs). And it did seem all connected. Companies successfully raised more than $3 billion through ICOs in 2017, for example, some of them online lending companies.

ETHLend and SALT, blockchain-based p2p lenders, each raised $16.2 million and $48.5 million respectively through ICOs. What’s more, their crypto market caps currently stand at $325 million and $754 million respectively. The latter is nearly twice as valuable as online lender OnDeck. The founder of Ripple, meanwhile, briefly became one of the richest men in the entire world.

ETHLend and SALT, blockchain-based p2p lenders, each raised $16.2 million and $48.5 million respectively through ICOs. What’s more, their crypto market caps currently stand at $325 million and $754 million respectively. The latter is nearly twice as valuable as online lender OnDeck. The founder of Ripple, meanwhile, briefly became one of the richest men in the entire world.

Whether these valuations are overdone is besides the point. A smart phone is all that’s required to get in on the action and trade thousands of cryptocurrencies online, many of which move up and down by astronomical percentages over the course of a day. Becoming a millionaire overnight by hitting on the right one is a dream sought after by many. And young people, especially millennials, are become unconsciously comfortable transacting in non-government-backed currencies through technology that completely shuts out banks.

And that may be the shift in all of this to pay attention to. It isn’t that a local restaurant is going to collateralize their Bitcoin to get a loan and outcompete an MCA company, but that a portion of the monetary system eventually starts to sidestep banks.

Trying to collect on that judgment? Good luck tracing the money in cryptos.

Need to freeze funds? You can’t freeze someone’s Bitcoins if they’ve got them stored on their own hardware.

Evaluating a business’s bank statements? The transactions can only be verified on a blockchain.

You might not believe me, but it’s incredibly likely that you’ve encountered a client that has defaulted on an MCA or loan whose stash of money has been obscured in cryptos all the while their bank statements appear to show insolvency.

It’s also likely that you’ve encountered a client that has used the proceeds of their MCA or loan to buy a crypto. Maybe not the whole amount, but with some of it. One study, for example, revealed that 18% of people have purchased Bitcoin using credit. Bloomberg reported that the phrase “buy bitcoin with credit card,” just recently spiked to an all-time high.

People are even taking out mortgages to buy Bitcoin, according to CNBC.

If you think cryptocurrency is an industry completely independent of your business, consider that the market cap of cryptocurrencies is currently valued at more than $700 billion. That’s nearly twice the market cap of Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan, COMBINED. The #3 cryptocurrency by market cap, Ripple, is being pitched almost entirely to traditional financial institutions.

Bet all you want on the prediction that this bubble will burst. Maybe it will. But the underlying technology, transacting without banks in non-government backed currencies that may be difficult to trace and recover, is a genie that’s not returning to its bottle anytime soon.

In the meantime, now might be a good time to poll your employees or colleagues about their knowledge or use of cryptocurrency. You may be surprised by what you find, especially among the younger crowd.

——–

Disclaimer: I currently hold a material amount of Ether, the currency of the Ethereum blockchain.