Stories

Financial Service Associations Urge Legislation on IRS Income Verification

January 25, 2024 The IRS doesn’t want financial service companies to be able to verify the income of customers, at least not through official channels like the Income Verification Express Services (IVES) system. On January 2 and 3, the IRS announced it would only allow IVES transcripts to be made available “to mortgage lending firms for the sole purpose of obtaining a mortgage on residential or commercial real property (land and buildings).” Government agencies will also not be allowed to use IVES.

The IRS doesn’t want financial service companies to be able to verify the income of customers, at least not through official channels like the Income Verification Express Services (IVES) system. On January 2 and 3, the IRS announced it would only allow IVES transcripts to be made available “to mortgage lending firms for the sole purpose of obtaining a mortgage on residential or commercial real property (land and buildings).” Government agencies will also not be allowed to use IVES.

“The IRS is implementing the provisions of the Taxpayer First Act (P. Law 116-25) with increased privacy and security requirements for access to confidential tax information,” it announced. “If tax transcript information is required by your firm for other than securing a mortgage, we recommend requesting it directly from the taxpayer.”

But relying on getting the information directly from the taxpayer defeats the whole purpose in more ways than one, many financial service trade associations say. On Wednesday, a letter jointly signed by the American Bankers Association, America’s Credit Unions, American Fintech Council, Consumer Data Industry Association, Electronic Transactions Association, Financial Technology Association, Innovative Lending Platform Association, Independent Community Bankers Association, Mortgage Bankers Association, Responsible Business Lending Coalition, and Small Business Finance Association urged senior ranking members of Congress to pass H.R. 3335. Dubbed the IRS eIVES Modernization and Anti-Fraud Act, it would “ensure the IRS follows the original intent of Congress to modernize the system and prevent disruptions to the consumer and commercial lending industries.”

Update on Connecticut Commercial Financing Disclosure Bill

March 28, 2022The Connecticut commercial financing disclosure bill first reported by deBanked on March 3rd is still in play. SB272, written similarly to the first draft of the recently passed New York legislation, has been met with both support and opposition.

Supportive

- Connecticut Bankers Association (but with amendments)

- Responsible Business Lending Coalition

- Innovative Lending Platform Association

Opposed

- Electronic Transactions Association

- Revenue Based Finance Coalition

- Small Business Finance Association

Connecticut Introduces Commercial Financing Disclosure and Double Dipping Bill

March 20, 2021 Ever since New York State Senator George Borrello famously questioned the meaning of “double dipping” in a commercial financing transaction, states have rushed to include the term in proposed laws despite no one knowing exactly what it means.

Ever since New York State Senator George Borrello famously questioned the meaning of “double dipping” in a commercial financing transaction, states have rushed to include the term in proposed laws despite no one knowing exactly what it means.

The latest state is Connecticut, which introduced SB 745 in February, an “Act Requiring Certain Financing Disclosures.” It is essentially a copy & paste of New York’s recent law which is slated to go into effect in June.

The Connecticut bill similarly applies to factoring, merchant cash advance, business lending and more. It was introduced by State Senator Saud Anwar (D).

A hearing held on March 2nd, drew testimony from the Commercial Finance Coalition, Small Business Finance Association, Electronic Transactions Association, Innovative Lending Platform Association, and Secured Finance Network.

If the bill passes, it is designed to go into effect in October of this year.

The FTC Wants To Police Small Business Finance

October 22, 2019 On May 23, the Federal Trade Commission launched an investigation into unfair or deceptive practices in the small business financing industry, including by merchant cash advance providers.

On May 23, the Federal Trade Commission launched an investigation into unfair or deceptive practices in the small business financing industry, including by merchant cash advance providers.

The agency is looking into, among other things, whether both financial technology companies and merchant cash advance firms are making misrepresentations in their marketing and advertising to small businesses, whether they employ brokers and lead-generators who make false and misleading claims, and whether they engage in legal chicanery and misconduct in structuring contracts and debt-servicing.

Evan Zullow, senior attorney at the FTC’s consumer protection division, told deBanked that the FTC is, moreover, investigating whether fintechs and MCAs employ “problematic,” “egregious” and “abusive” tactics in collecting debts. He cited such bullying actions as “making false threats of the consequences of not paying a debt,” as well as pressuring debtors with warnings that they could face jail time, that authorities would be notified of their “criminal” behavior, contacting third-parties like employers, colleagues, or family members, and even issuing physical threats.

“Broadly,” Zullow said in a telephone interview, “our work and authority reaches the full life cycle of the financing arrangement.” He added: “We’re looking closely at the conduct (of firms) in this industry and, if there’s unlawful conduct, we’ll take law enforcement action.”

Zullow declined to identify any targets of the FTC inquiry. “I can’t comment on nonpublic investigative work,” he said.

The FTC investigation is one of several regulatory, legislative and law enforcement actions facing the merchant cash advance industry, which was triggered by a Bloomberg exposé last winter alleging sharp practices by some MCA firms.

The FTC investigation is one of several regulatory, legislative and law enforcement actions facing the merchant cash advance industry, which was triggered by a Bloomberg exposé last winter alleging sharp practices by some MCA firms.

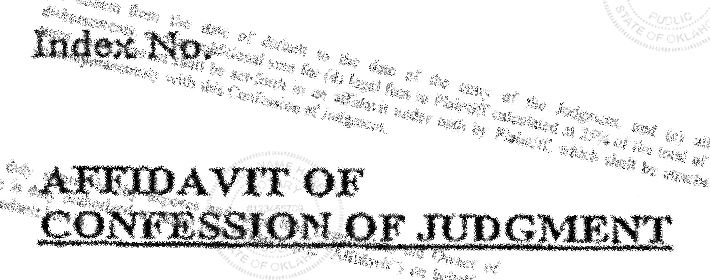

The Bloomberg series told of high-cost financings, of MCA firms’ draining debtors’ bank accounts, and of controversial collections practices in which debtors signed contracts that included “confessions of judgment.”

The FTC long ago outlawed the use of COJs in consumer loan contracts and several states have banned their use in commercial transactions. In September, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed legislation prohibiting the use of COJs in New York State courts for out-of-state residents. And there is a bipartisan bill pending in the U.S. Senate authored by Florida Republican Marco Rubio and Ohio Democrat Sherrod Brown to outlaw COJs nationwide.

Mark Dabertin, a senior attorney at Pepper Hamilton, described the FTC’s investigation of small business financing as a “significant development.” But he also said that the agency’s “expansive reading of the FTC Act arguably presents the bigger news.” Writing in a legal memorandum to clients, Dabertin added: “It opens the door to introducing federal consumer protection laws into all manner of business-to-business conduct.”

FTC attorney Zullow told deBanked, “We don’t think it’s new or that we’re in uncharted waters.”

The FTC inquiry into alternative small business financing is not the only investigation into the MCA industry. Citing unnamed sources, The Washington Post reported in June that the Manhattan district attorney is pursuing a criminal investigation of “a group of cash advance executives” and that the New York State attorney general’s office is conducting a separate civil probe.

The FTC’s investigation follows hard on the heels of a May 8 forum on small business financing. Labeled “Strictly Business,” the proceedings commenced with a brief address by FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra, who paid homage to the vital role that small business plays in the U.S. economy. “Hard work and the creativity of entrepreneurs and new small businesses helped us grow,” he said.

But he expressed concern that entrepreneurship and small business formation in the U.S. was in decline. According to census data analyzed by the Kaufmann Foundation and the Brookings Institution, the commissioner noted, the number of new companies as a share of U.S. businesses has declined by 44 percent from 1978 to 2012.

“It’s getting harder and harder for entrepreneurs to launch new businesses,” Chopra declared. “Since the 1980s, new business formation began its long steady decline. A decade ago births of new firms started to be eclipsed by deaths of firms.”

Chopra singled out one-sided, unjust contracts as a particularly concerning phenomenon. “One of the most powerful weapons wielded by firms over new businesses is the take-it-or-leave-it contract,” he said, adding: “Contracts are ways that we put promises on paper. When it comes to commerce, arm’s length dealing codified through contracts is a prerequisite for prosperity. “But when a market structure requires small businesses to be dependent on a small set of dominant firms — or firms that don’t engage in scrupulous business practices — these incumbents can impose contract terms that cement dominance, extract rents, and make it harder for new businesses to emerge and thrive.”

As the panel discussions unfolded, representatives of the financial technology industry (Kabbage, Square Capital and the Electronic Transactions Association) as well as executives in the merchant cash advance industry (Kapitus, Everest Business Financing, and United Capital Source) sought to emphasize the beneficial role that alternative commercial financiers were playing in fostering the growth of small businesses by filling a void left by banks.

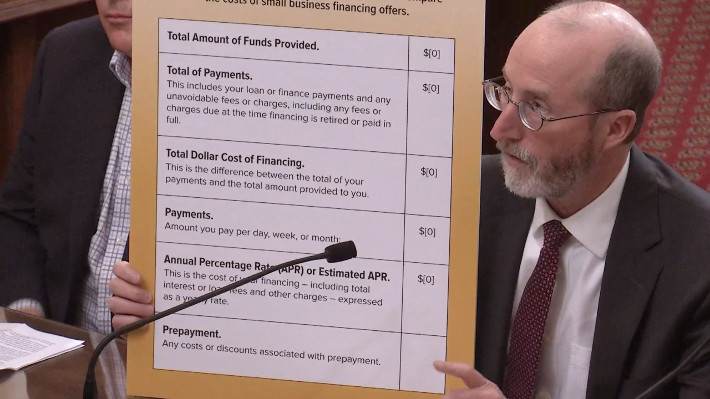

The fintechs went first. In general, they stressed the speed and convenience of their loans and lines of credit, and the pioneering innovations in technology that allowed them to do deeper dives into companies seeking credit, and to tailor their products to the borrower’s needs. Panelists cited the “SMART Box” devised by Kabbage and OnDeck as examples of transparency. (Accompanying those companies’ loan offers, the SMART Box is modeled on the uniform terms contained in credit card offerings, which are mandated by the Truth in Lending Act. TILA does not pertain to commercial debt transactions.)

Sam Taussig, head of global policy at Kabbage, explained that his company typically provides loans to borrowers with five to seven employees — “truly Main Street American small businesses” — that are seeking out “project-based financing” or “working capital.”

Sam Taussig, head of global policy at Kabbage, explained that his company typically provides loans to borrowers with five to seven employees — “truly Main Street American small businesses” — that are seeking out “project-based financing” or “working capital.”

“The average small business according to our research only has about 27 days of cash flow on hand,” Taussig told the fintech panel, FTC moderators and audience members. “So if you as a small business owner need to seize an opportunity to expand your revenue or (have) a one-off event — such as the freezer in your ice cream store breaks — it’s very difficult to access that capital quickly to get back to business or grow your business.”

Taussig contrasted the purpose of a commercial loan with consumer loans taken out to consolidate existing debt or purchase a consumer product that’s “a depreciating asset.” Fintechs, which typically supply lightning-quick loans to entrepreneurs to purchase equipment, meet payrolls, or build inventory, should be judged by a different standard.

A florist needs to purchase roses and carnations for Mother’s Day, an ice-cream store must replenish inventory over the summer, an Irish pub has to stock up on beer and add bartenders at St. Patrick’s Day.

The session was a snapshot of not just the fintech industry but of the state of small business. Lewis Goodwin, the head of banking services at Square Capital, noted that small businesses account for 48% of the U.S. workforce. Yet, he said, Square’s surveys show that 70% of them “are not able to get what they want” when they seek financing.

Square, he said, has made 700,000 loans for $4.5 billion in just the past few years, the platform’s average loan is between $6,000 and $7,000, and it never charges borrowers more than 15% of a business’s daily receipts. The No. 1 alternative for small businesses in need of capital is “friends and family,” Goodwin said, “and that’s a tough bank to go back to.”

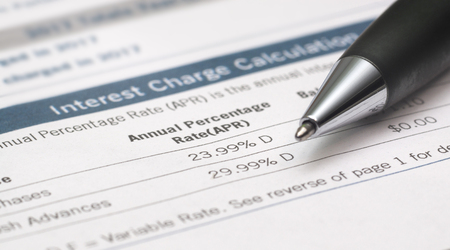

Panelist Gwendy Brown, vice-president of research and policy at the Opportunity Fund, a non-profit microfinance organization, provided the fintechs with their most rocky moment when she declared that small businesses turning up at her fund were typically paying an annual percentage rate of 94 percent for fintech loans. And while most small business owners were knowledgeable about their businesses — the florists “know flowers in and out,” for example — they are often bewildered by the “landscape” of financial product offerings.

Panelist Gwendy Brown, vice-president of research and policy at the Opportunity Fund, a non-profit microfinance organization, provided the fintechs with their most rocky moment when she declared that small businesses turning up at her fund were typically paying an annual percentage rate of 94 percent for fintech loans. And while most small business owners were knowledgeable about their businesses — the florists “know flowers in and out,” for example — they are often bewildered by the “landscape” of financial product offerings.

“Sophistication as a business owner,” Brown said, “does not necessarily equate into sophistication in being able to assess finance options.”

Panelist Claire Kramer Mills, vice-president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, reported that the country’s banks have made a dramatic exit from small business lending over the past ten years. A graphic would show that bank loans of more than $1 million have risen dramatically over the past decade but, she said, “When you look at the small loans, they’ve remained relatively flat and are not back to pre-crisis levels.”

Mills also said that 50% of small businesses in the Federal Reserve’s surveys “tell us that they have a funding shortfall of some sort or another. It’s more stark when you look at women-owned business, black or African-American owned businesses, and Latino-owned businesses.”

On the merchant cash advance panel there was less opportunity to dazzle the regulators and audience members with accounts of state-of-the-art technology and the ability to aggregate mountains of data to make online loans in as few as seven minutes, as Kabbage’s Taussig noted the fintech is wont to do.

Instead, industry panelists endeavored to explain to an audience — which included skeptical regulators, journalists, lawyers and critics — the precarious, high-risk nature of an MCA or factoring product, how it differs from a loan, and the upside to a merchant opting for a cash advance. (To their credit, one attendee told deBanked, the audience also included members of the MCA industry interested in compliance with federal law.)

Instead, industry panelists endeavored to explain to an audience — which included skeptical regulators, journalists, lawyers and critics — the precarious, high-risk nature of an MCA or factoring product, how it differs from a loan, and the upside to a merchant opting for a cash advance. (To their credit, one attendee told deBanked, the audience also included members of the MCA industry interested in compliance with federal law.)

A merchant cash advance is “a purchase of future receipts,” Kate Fisher, an attorney at Hudson Cook in Baltimore, explained. “The business promises to deliver a percentage of its revenue only to the extent as that revenue is created. If sales go down,” she explained, “then the business has a contractual right to pay less. If sales go up, the business may have to pay more.”

As for the major difference between a loan and a merchant cash advance: the borrower promises to repay the lender for the loan, Fisher noted, but for a cash advance “there’s no absolute obligation to repay.”

Scott Crockett, chief executive at Everest Business Funding, related two anecdotes, both involving cash advances to seasonal businesses. In the first instance, a summer resort in Georgia relied on Everest’s cash advances to tide it over during the off-season.

When the resort owner didn’t call back after two seasonal advances, Crockett said, Everest wanted to know the reason. The answer? The resort had been sold to Marriott Corporation. Thanking Everest, Crockett said, the former resort-owners reported that without the MCA, he would likely have sold off a share of his business to a private equity fund or an investor.

By providing a cash advance Everest acted “more like a temporary equity partner,” Crockett remarked.

In the second instance, a restaurant in the Florida Keys that relied on a cash advance from Everest to get through the slow summer season was destroyed by Hurricane Irma. “Thank God no one was hurt,” Crockett said, “but the business owner didn’t owe us anything. We had purchased future revenues that never materialized.”

The outsized risk borne by the MCA industry is not confined entirely to the firm making the advance, asserted Jared Weitz, chief executive at United Capital Service, a consultancy and broker based in Great Neck, N.Y. It also extends to the broker. Weitz reported that a big difference between the MCA industry and other funding sources, such as a bank loan backed by the Small Business Administration, is that ”you are responsible to give that commission back if that merchant does not perform or goes into an actual default up to 90 days in.

“I think that’s important,” Weitz added, “because on (both) the broker side and on the funding side, we really are taking a ride with the merchant to make sure that the business succeeds.”

FTC’s panel moderators prodded the MCA firms to describe a typical factor rate. Jesse Carlson, senior vice-president and general counsel at Kapitus, asserted that the factor rate can vary, but did not provide a rate.

FTC’s panel moderators prodded the MCA firms to describe a typical factor rate. Jesse Carlson, senior vice-president and general counsel at Kapitus, asserted that the factor rate can vary, but did not provide a rate.

“Our average financing is approximately $50,000, it’s approximately 11-12 months,” he said. “On a $50,000 funding we would be purchasing $65,000 of future revenue of that business.”

The FTC moderator asked how that financing arrangement compared with a “typical” annual percentage rate for a small business financing loan and whether businesses “understand the difference.”

Carlson replied: “There is no interest rate and there is no APR. There is no set repayment period, so there is no term.” He added: “We provide (the) total cost in a very clear disclosure on the first page of all of our contracts.”

Ami Kassar, founder and chief executive of Multifunding, a loan broker that does 70% of its work with the Small Business Administration, emerged as the panelist most critical of the MCA industry. If a small business owner takes an advance of $50,000, Kassar said, the advance is “often quoted as a factor rate of 20%. The merchant thinks about that as a 20% rate. But on a six-month payback, it’s closer to 60-65%.”

He asserted that small businesses would do better to borrow the same amount of money using an SBA loan, pay 8 1/4 percent and take 10 years to pay back. It would take more effort and the wait might be longer, but “the impact on their cash flow is dramatic” — $600 per month versus $600 a day, he said — “compared to some of these other solutions.”

Kassar warned about “enticing” offers from MCA firms on the Internet, particularly for a business owner in a bind. “If you jump on that train and take a short-term amortization, oftentimes the cash flow pressure that creates forces you into a cycle of short-term renewals. As your situation gets tougher and tougher, you get into situations of stacking and stacking.”

On a final panel on, among other matters, whether there is uniformity in the commercial funding business, panelists described a massive muddle of financial products.

Barbara Lipman: project manager in the division of community affairs with the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, said that the central bank rounded up small businesses to do some mystery shopping. The cohort — small businesses that employ fewer than 20 employees and had less than $2 million in revenues — pretended to shop for credit online.

As they sought out information about costs and terms and what the application process was like, she said, “They’re telling us that it’s very difficult to find even some basic information. Some of the lenders are very explicit about costs and fees. Others however require a visitor to go to the website to enter business and personal information before finding even the basics about the products.” That experience, Lipman said, was “problematic.”

She also said that, once they were identified as prospective borrowers on the Internet, the Fed’s shoppers were barraged with a ceaseless spate of online credit offers.

John Arensmeyer, chief executive at Small Business Majority, an advocacy organization, called for greater consistency and transparency in the marketplace. “We hear all the time, ‘Gee, why do we need to worry about this? These are business people,’” he said. “The reality is that unless a business is large enough to have a controller or head of accounting, they are no more sophisticated than the average consumer.

“Even about the question of whether a merchant cash advance is a loan or not,” Arensmeyer added. “To the average small business owner everything is a loan. These legal distinctions are meaningless. It’s pretty much the Wild West.”

In the aftermath of the forum, the question now is: What is the FTC likely to do?

In the aftermath of the forum, the question now is: What is the FTC likely to do?

Zullow, the FTC attorney, referred deBanked to several recent cases — including actions against Avant and SoFi — in which the agency sanctioned online lenders that engaged in unfair or deceptive practices, or misrepresented their products to consumers.

These included a $3.85 million settlement in April, 2019, with Avant, an online lending company. The FTC had charged that the fintech had made “unauthorized charges on consumers’ accounts” and “unlawfully required consumers to consent to automatic payments from their bank accounts,” the agency said in a statement.

In the settlement with SoFi, the FTC alleged that the online lender, “made prominent false statements about loan refinancing savings in television, print, and internet advertisements.” Under the final order, “SoFi is prohibited from misrepresenting to consumers how much money consumers will save,” according to an FTC press release.

But these are traditional actions against consumer lenders. A more relevant FTC action, says Pepper Hamilton attorney Dabertin, was the FTC’s “Operation Main Street,” a major enforcement action taken in July, 2018 when the agency joined forces with a dozen law enforcement partners to bring civil and criminal charges against 24 alleged scam artists charged with bilking U.S. small businesses for more than $290 million.

In the multi-pronged campaign, which Zullow also cited, the FTC collaborated with two U.S. attorneys’ offices, the attorneys general of eight states, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and the Better Business Bureau. According to the FTC, the strike force took action against six types of fraudulent schemes, including:

- Unordered merchandise scams in which the defendants charged consumers for toner, light bulbs, cleaner and other office supplies that they never ordered;

- Imposter scams in which the defendants use deceptive tactics, such as claiming an affiliation with a government or private entity, to trick consumers into paying for corporate materials, filings, registrations, or fees;

- Scams involving unsolicited faxes or robocalls offering business loans and vacation packages.

If there remains any question about whether the FTC believes itself constrained from acting on behalf of small businesses as well as consumers, consider the closing remarks at the May forum made by Andrew Smith, director of the agency’s bureau of consumer protection.

“(O)ur organic statute, the FTC Act, allows us to address unfair and deceptive practices even with respect to businesses,” Smith declared, “And I want to make clear that we believe strongly in the importance of small businesses to the economy, the importance of loans and financing to the economy.

Smith asserted that the agency could be casting a wide net. “The FTC Act gives us broad authority to stop deceptive and unfair practices by nonbank lenders, marketers, brokers, ISOs, servicers, lead generators and collectors.”

As fintechs and MCAs, in particular, await forthcoming actions by the commission, their membership should take pains to comport themselves ethically and responsibly, counsels Hudson Cook attorney Fisher. “I don’t think businesses should be nervous,” she says, “but they should be motivated to improve compliance with the law.”

She recommends that companies make certain that they have a robust vendor-management policy in place, and that they review contracts with ISOs. Companies should also ensure that they have the ability to audit ISOs and monitor any complaints. “Take them seriously and respond,” Fisher says.

Companies would also do well to review advertising on their websites to ascertain that claims are not deceptive, and see to it that customer service and collections are “done in a way that is fair and not deceptive,” she says, adding of the FTC investigation: “This is a wake-up call.”

California DBO Making Progress On Finalizing Rules Required By The New Disclosure Law

July 29, 2019 Last October, California Governor Jerry Brown signed a new commercial finance disclosure bill into law. The bill, SB 1235, was a major source of debate in 2018 because of its tricky language to pressure factors and merchant cash advance providers into stating an Annual Percentage Rate on contracts with California businesses. The final version of the bill, however, delegated the final disclosure format requirements to the State’s primary financial regulator, the Department of Business Oversight (DBO).

Last October, California Governor Jerry Brown signed a new commercial finance disclosure bill into law. The bill, SB 1235, was a major source of debate in 2018 because of its tricky language to pressure factors and merchant cash advance providers into stating an Annual Percentage Rate on contracts with California businesses. The final version of the bill, however, delegated the final disclosure format requirements to the State’s primary financial regulator, the Department of Business Oversight (DBO).

The DBO then issued a public invitation to comment on how that format should work. They got 34 responses. Among them were Affirm, ApplePie Capital, Electronic Transactions Association, Commercial Finance Coalition, Fora Financial, Equipment Leasing and Finance Association, Innovative Lending Platform Association, International Factoring Association, Kapitus, OnDeck, PayPal, Rapid Finance, Small Business Finance Association, and Square Capital.

On Friday, the DBO published a draft of its rules along with a public invitation to comment further. The 32-page draft can be downloaded here. The opportunity to comment on this version of the rules ends on Sept 9th.

You can review the comments that companies submitted previously here.

Get The Affidavit or Waive It? Examining Confessions of Judgment

February 1, 2019 Caton Hanson, the chief legal officer and co-founder of the online credit-reporting and business-to-business matchmaker Nav, says that his Salt Lake City-based company would not associate with a small-business financier that included “confessions of judgment” in its credit contracts.

Caton Hanson, the chief legal officer and co-founder of the online credit-reporting and business-to-business matchmaker Nav, says that his Salt Lake City-based company would not associate with a small-business financier that included “confessions of judgment” in its credit contracts.

“If we understood that any of our merchant cash advance partners were using confessions of judgment as a means to enforce contracts,” Hanson told deBanked, “we would view that as abusive and distance ourselves from those partners. As a venture-backed company,” Hanson adds, “we have some significant investors, including Goldman Sachs, and I’m sure they would support us.”

Steve Denis, executive director of the Small Business Finance Association, which represents companies in the merchant cash advance (MCA) industry, says that, as an organization, “We’ve taken a strong stance against confessions of judgment.”

He reports that his Washington, D.C.-based trade group is prepared to work with legislators and policy-makers of any political party, regulators, business groups and the news media “to ban that type of practice.

“We’re fighting against the image that we’re payday lenders for business,” Denis says of the merchant cash advance industry. “We’re trying to figure out internally what we can do to stop that from happening and we have been speaking to members of Congress and their staff.”

“Confessions of judgment,” says Cornelius Hurley, a law professor at Boston University and executive director of the Online Lending Policy Institute, “are to the merchant cash advance industry what mandatory arbitration is to banks. Neither enforcement device reflects well on the firms that use them.”

These are just some of the reactions from members of the alternative lending and financial technology community to a blistering series of articles published by Bloomberg News on the use—and alleged misuse—of confessions of judgment (COJs) by merchant cash advance companies. The series charges the MCA industry with gulling unwary small businesses by not only charging high interest rates for quick cash but of using confession-laden contracts to seize their assets without due process.

The Bloomberg articles also reported that it doesn’t matter in which state the small business debtors reside. By bringing legal action in New York State courts, MCA companies have been able to use enforcement powers granted by the confessions to collect an estimated $1.5 billion from some 25,000 businesses since 2012.

“I don’t think anyone can read that series of articles and honestly say what went on were good practices and in the best interest of small business,” says SBFA’s Denis, noting that none of the companies cited in the Bloomberg series belonged to his trade group. “It’s shocking to see some companies in our space doing things we’d classify as predatory,” he adds. “As an industry we’re becoming more sophisticated, but there are still some bad actors out there.”

A confession of judgment is a hand-me-down to U.S. jurisprudence from old English law. The term’s quaint, almost religious phrasing evokes images of drafty buildings, bleak London fog, and dowdy barristers in powdered wigs and solemn black gowns. (And perhaps debtor prisons as well.)

A confession of judgment is a hand-me-down to U.S. jurisprudence from old English law. The term’s quaint, almost religious phrasing evokes images of drafty buildings, bleak London fog, and dowdy barristers in powdered wigs and solemn black gowns. (And perhaps debtor prisons as well.)

Yet while the legal provision’s wings have been clipped—the Federal Trade Commission banned the use of confessions of judgment in consumer credit transactions in 1985 and many states prohibit their use outright or in such cases as residential real estate contracts—COJs remain alive and well in many U.S. jurisdictions for commercial credit transactions.

Even so, most states where COJs are in use, such as California and Pennsylvania, have adopted safeguards. Here’s how the San Francisco law firm Stimmel, Stimmel and Smith describes a COJ.

“A confession of judgment is a private admission by the defendant to liability for a debt without having a trial. It is essentially a contract—or a clause with such a provision—in which the defendant agrees to let the plaintiff enter a judgment against him or her. The courts have held that such a process constitutes the defendant’s waiving vital constitutional rights, such as the right to due process, thus (the courts) have imposed strict requirements in order to have the confession of judgment enforceable.”

In California, those “strict requirements” include not only that a written statement be “signed and verified by the defendant under oath,” but that it must be accompanied by an independent attorney’s “declaration.” If no independent attorney signs the declaration or—worse still—the plaintiff’s attorney signs the document, the confession is invalid.

But if the confession is “properly executed,” the plaintiff is entitled to use the full panoply of tools for collection of the judgment, including “writs of execution” and “attachment of wages and assets.”

In Pennsylvania, confessions of judgment are nearly as commonplace as Philadelphia Eagles’ and Pittsburgh Steelers’ fans, particularly in commercial real estate transactions. Says attorney Michael G. Louis, a partner at Philadelphia-area law firm Macelree Harvey, “They may go back to old English law, but if you get a business loan or commercial lease in Pennsylvania, a confession of judgment will be in there. It’s illegal in Pennsylvania for a consumer loan or residential real estate. But unless it’s a national tenant with a ton of bargaining power—a big anchor store and the owner of the shopping center really wants them—95% of commercial leasing contracts have them.

In Pennsylvania, confessions of judgment are nearly as commonplace as Philadelphia Eagles’ and Pittsburgh Steelers’ fans, particularly in commercial real estate transactions. Says attorney Michael G. Louis, a partner at Philadelphia-area law firm Macelree Harvey, “They may go back to old English law, but if you get a business loan or commercial lease in Pennsylvania, a confession of judgment will be in there. It’s illegal in Pennsylvania for a consumer loan or residential real estate. But unless it’s a national tenant with a ton of bargaining power—a big anchor store and the owner of the shopping center really wants them—95% of commercial leasing contracts have them.

“And any commercial bank in Pennsylvania worth its salt includes them in their commercial loan documents,” Louis adds.

Pennsylvania’s laws governing COJs contain a number of additional safeguards. For example, the confession of judgment is part of the note, guaranty or lease agreement—not a separate document—but must be written in capital letters and highlighted. One of the defenses that used to be raised against COJs, Louis says, was that a contractual document was written in fine print “but we haven’t seen fine print for years.”

Other reforms in Pennsylvania have come about, moreover, as a result of a 1994 case known as “Jordan v. Fox Rothschild.” Says Louis: “It used to be lot worse. You used to be able to file a confession of judgment and levy on a defendant’s bank account before he knew what happened. It was brutal. But after the Fox Rothschild case, they changed the law to prevent taking away a defendant’s right of notice and the opportunity to be heard.”

Because of that case, which takes its name from the Fox Rothschild law firm and involved a dispute between a Philadelphia landlord renting commercial space to Jordan, a tenant, the law governing COJs in Pennsylvania requires, among other things, a 30-day notice before a creditor or landlord can execute on the confession. During that period the defendant has the opportunity to stay the execution or re-open the case for trial.

Defenses against the execution of a COJ can entail arguments that creditors failed to comply with the proper language or procedures in drafting the document. But the most successful argument, Louis says, is a “factual defense.” Louis cites the case of a retail clothing store renting space in a shopping center that has a leaky roof. In the 30-day notice period after the landlord invoked the confession of judgment, the tenant was able to demonstrate to the court that he had asked the landlord “ten times” to fix the roof before spending the rent money on roof repairs. In such a case, the courts will grant the defendant a new trial but, Louis says, the parties typically reach a settlement. “Banks generally will waive a jury trial,” he notes, “because they don’t want to take a chance of getting hammered by a jury.”

Defenses against the execution of a COJ can entail arguments that creditors failed to comply with the proper language or procedures in drafting the document. But the most successful argument, Louis says, is a “factual defense.” Louis cites the case of a retail clothing store renting space in a shopping center that has a leaky roof. In the 30-day notice period after the landlord invoked the confession of judgment, the tenant was able to demonstrate to the court that he had asked the landlord “ten times” to fix the roof before spending the rent money on roof repairs. In such a case, the courts will grant the defendant a new trial but, Louis says, the parties typically reach a settlement. “Banks generally will waive a jury trial,” he notes, “because they don’t want to take a chance of getting hammered by a jury.”

A number of states, including Florida and Massachusetts ban the use of confessions of judgment. That’s one big reason that Miami attorney Roger Slade, a partner at Haber Law, advises clients that “there’s no place like home.” In other words: commercial contracts should specify that any legal disputes will be adjudicated in Florida. “It’s like having home field advantage in the NFL playoffs,” Slade remarked to deBanked. “You don’t want to play on someone else’s turf.”

He has also been warning Floridians for several years against the way that COJs were treated by New York courts. Writing in the blog, “The Florida Litigator,” Slade—a native New Yorker who is certified to practice law there as well as in Florida counseled in 2012: “If you live in New York, a creditor can have your client sign a confession of judgment and, in the event of a default on a loan, can march directly to the courthouse and have a final judgment entered by the clerk. That’s right—no complaint, no summons, no time to answer, no two-page motion to dismiss. The creditor gets to go right for the jugular.”

In addition, because of the “full faith and credit clause of the U.S. Constitution,” Slade notes in an interview, a contract that’s enforced by the New York courts must be honored in Florida. “Courts in Florida have no choice,” Slade says. “It’s a brutal system and it’s unfortunate.”

In December, two U.S. senators from opposing parties—Ohio Democrat Sherrod Brown and Florida Republican Marco Rubio—introduced bipartisan legislation to amend both the Federal Trade Commission Act and Truth in Lending Act to do away with COJs. Their legislative proposal reads:

“(N)o creditor may directly or indirectly take or receive from a borrower an obligation that constitutes or contains a congnovit or confession of judgment (for purposes other than executory process in the State of Louisiana), warrant of attorney, or other waiver of the right to notice and the opportunity to be heard in the event of suit or process theron.”

But with a dysfunctional and divided federal government, warring power factions in Washington, and an influential financial industry, there’s no telling how the legislation will fare. Meantime, the New York State attorney general’s office announced in December that it will investigate the use of COJs following the Bloomberg series. And New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has declared support for legislation that will, among other things, prohibit the use of confessions in judgment for small business credit contracts under $250,000 and restrict judgments by New York courts to in-state parties.

But if New York State or Congressional legislation are adopted it can have “unintended consequences” to merchant cash advance firms in the Empire State—and to their small business customers as well—asserts the general counsel for one MCA firm. “Losing the confession of judgment will be removing what little safety net there is in a risky industry,” the attorney says, noting that the industry has roughly a 15% default rate.

“It is not as powerful a tool as the Bloomberg news stories would have you believe,” this attorney, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told deBanked. “The suggestion seems to be that the MCAs can use the confession of judgment to get back the total amount of money due—and then some—while leaving a trail of dead bodies behind. But that’s not the case.

“What is much more likely to be the case,” he adds, “is that MCA companies try to get the defaulting merchant back on track. And—probably more than we should and only after we’ve tried to reach out to them and failed—do we then reluctantly use the COJ as a last resort. At which point we hope we can recover some part of our exposure. The numbers vary, but the losses are always in the thousands of dollars. These are not micro-transactions.

“What’s going to happen,” he concludes, “is that It will not make sense for us to work with those merchants most in need of working capital. The unfortunate reality is that businesses who don’t have collateral and can’t get a Small Business Administration product will be left out in the cold.”

All of which prompts BU professor Hurley to argue that the “Swiss cheese” system of financial regulation among the 50 states continues to be a root cause of regulatory confusion. Echoing Miami attorney Slade’s concern about New York courts’ dictating to Florida citizens, Hurley likens the situation governing COJs with the disorderly array of state laws governing usury regulations.

In the 1978 “Marquette” decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a Nebraska bank, First of Omaha, could issue credit cards in Minnesota and charge interest rates that exceeded the usury rate ceiling in the Gopher State. Since then, usury rates enacted by state legislatures have become virtually unenforceable.

“The problem we’re seeing with confessions of judgment is a subset of the usury situation,” Hurley says. “One state’s disharmony becomes a cancer on the whole system. It’s a throwback to Colonial times with 50 states each having their own jurisdictions—and it doesn’t work.”

Hurley’s Online Lending Policy Institute has joined with the Electronic Transactions Association and recruited a phalanx of “academics, non-banks, law firms and other trade associations as members or affiliates” to form the Fintech Harmonization Task Force. It is monitoring the efforts by the 50 states to align their regulatory oversight of the booming financial technology industry which was recently recommended by a U.S. Treasury report.

Hurley’s Online Lending Policy Institute has joined with the Electronic Transactions Association and recruited a phalanx of “academics, non-banks, law firms and other trade associations as members or affiliates” to form the Fintech Harmonization Task Force. It is monitoring the efforts by the 50 states to align their regulatory oversight of the booming financial technology industry which was recently recommended by a U.S. Treasury report.

Tom Ajamie, who practices law in New York and Houston and has won multimillion-dollar, blockbuster judgments against “dozens of financial institutions” including Wall Street investment firms, also argues for greater regulatory oversight. He urges greater funding and expansion of the powers of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to rein in “the anticipatory use” of confessions of judgment in commercial transactions.

However, notes Catherine Brennan, a partner at Hudson Cook in Baltimore, the job of protecting small businesses is outside the agency’s mandate. “The CFPB doesn’t have authority over commercial products as a general rule,” she explained in an interview. “Consumers are viewed as a vulnerable population in need of protections since the 1960’s.” As a society “we want protection for households because the consequences are high. A family could become homeless if they lose a house. Or (they) could lose employment if they lose a car and can’t drive. And there is also unequal bargaining power between lenders and consumers.

“Large institutions have lawyers to draft contracts and consumers have to agree on a take it or leave it basis. So there’s not a lot of negotiation and government has decided that consumers need protections, including a (Federal Trade Commission) ban on confessions of judgment.”

But Christopher Odinet, a law professor at the University of Oklahoma and a member of Hurley’s harmonization task force, sees the efforts of the federal government and the states to grapple with confessions of judgment as further recognition that small businesses have more in common with consumers than with big business. The COJ controversy follows on the recent passage of a commercial truth-in-lending bill by the State of California which, for the first time, stipulated that consumer-style disclosures should be included in business loans and financings under $500,000 made by non-bank financial organizations.

He cites the close-to-home example of an accomplished professional who got in over his head in financial dealings. “I recently observed a situation where a family member who is a very successful and affluent medical professional was relying on his own untrained business skills,” Odinet says. “He was about to enter into a sophisticated and complex business partnership relying on his intuition and general sense of confidence in the other party.”

Odinet says that he recommended that his relative hire a lawyer. Which, Odinet says, he did.

Less Than Perfect — New State Regulations

December 21, 2018

You could call California’s new disclosure law the “Son-in-Law Act.” It’s not what you’d hoped for—but it’ll have to do.

That’s pretty much the reaction of many in the alternative lending community to the recently enacted legislation, known as SB-1235, which Governor Jerry Brown signed into law in October. Aimed squarely at nonbank, commercial-finance companies, the law—which passed the California Legislature, 28-6 in the Senate and 72-3 in the Assembly, with bipartisan support—made the Golden State the first in the nation to adopt a consumer style, truth-in-lending act for commercial loans.

The law, which takes effect on Jan. 1, 2019, requires the providers of financial products to disclose fully the terms of small-business loans as well as other types of funding products, including equipment leasing, factoring, and merchant cash advances, or MCAs.

The financial disclosure law exempts depository institutions—such as banks and credit unions—as well as loans above $500,000. It also names the Department of Business Oversight (DBO) as the rulemaking and enforcement authority. Before a commercial financing can be concluded, the new law requires the following disclosures:

The financial disclosure law exempts depository institutions—such as banks and credit unions—as well as loans above $500,000. It also names the Department of Business Oversight (DBO) as the rulemaking and enforcement authority. Before a commercial financing can be concluded, the new law requires the following disclosures:

(1) An amount financed.

(2) The total dollar cost.

(3) The term or estimated term.

(4) The method, frequency, and amount of payments.

(5) A description of prepayment policies.

(6) The total cost of the financing expressed as an annualized rate.

The law is being hailed as a breakthrough by a broad range of interested parties in California—including nonprofits, consumer groups, and small-business organizations such as the National Federation of Independent Business. “SB-1235 takes our membership in the direction towards fairness, transparency, and predictability when making financial decisions,” says John Kabateck, state director for NFIB, which represents some 20,000 privately held California businesses.

“What our members want,” Kabateck adds, “is to create jobs, support their communities, and pursue entrepreneurial dreams without getting mired in a loan or financial structure they know nothing about.”

Backers of the law, reports Bloomberg Law, also included such financial technology companies as consumer lenders Funding Circle, LendingClub, Prosper, and SoFi.

But a significant segment of the nonbank commercial lending community has reservations about the California law, particularly the requirement that financings be expressed by an annualized interest rate (which is different from an annual percentage rate, or APR). “Taking consumer disclosure and annualized metrics and plopping them on top of commercial lending products is bad public policy,” argues P.J. Hoffman, director of regulatory affairs at the Electronic Transactions Association.

The ETA is a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing nearly 500 payments technology companies worldwide, including such recognizable names as American Express, Visa and MasterCard, PayPal and Capital One. “If you took out the annualized rate,” says ETA’s Hoffman, “we think the bill could have been a real victory for transparency.”

The ETA is a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing nearly 500 payments technology companies worldwide, including such recognizable names as American Express, Visa and MasterCard, PayPal and Capital One. “If you took out the annualized rate,” says ETA’s Hoffman, “we think the bill could have been a real victory for transparency.”

California’s legislation is taking place against a backdrop of a balkanized and fragmented regulatory system governing alternative commercial lenders and the fintech industry. This was recognized recently by the U.S. Treasury Department in a recently issued report entitled, “A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities: Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation.” In a key recommendation, the Treasury report called on the states to harmonize their regulatory systems.

As laudable as California’s effort to ensure greater transparency in commercial lending might be, it’s adding to the patchwork quilt of regulation at the state level, says Cornelius Hurley, a Boston University law professor and executive director of the Online Lending Policy Institute. “Now it’s every regulator for himself or herself,” he says.

Hurley is collaborating with Jason Oxman, executive director of ETA, Oklahoma University law professor Christopher Odinet, and others from the online-lending industry, the legal profession, and academia to form a task force to monitor the progress of regulatory harmonization.

For now, though, all eyes are on California to see what finally emerges as that state’s new disclosure law undergoes a rulemaking process at the DBO. Hoffman and others from industry contend that short-term, commercial financings are a completely different animal from consumer loans and are hoping the DBO won’t squeeze both into the same box.

Steve Denis, executive director of the Small Business Finance Association, which represents such alternative financial firms as Rapid Advance, Strategic Funding and Fora Financial, is not a big fan of SB-1235 but gives kudos to California solons—especially state Sen. Steve Glazer, a Democrat representing the Bay Area who sponsored the disclosure bill—for listening to all sides in the controversy. “Now, the DBO will have a comment period and our industry will be able to weigh in,” he notes.

While an annualized rate is a good measuring tool for longer-term, fixed-rate borrowings such as mortgages, credit cards and auto loans, many in the small-business financing community say, it’s not a great fit for commercial products. Rather than being used for purchasing consumer goods, travel and entertainment, the major function of business loans are to generate revenue.

A September, 2017, study of 750 small-business owners by Edelman Intelligence, which was commissioned by several trade groups including ETA and SBFA, found that the top three reasons businesses sought out loans were “location expansion” (50%), “managing cash flow” (45%) and “equipment purchases” (43%).

The proper metric to be employed for such expenditures, Hoffman says, should be the “total cost of capital.” In a broadsheet, Hoffman’s trade group makes this comparison between the total cost of capital of two loans, both for $10,000.

Loan A for $10,000 is modeled on a typical consumer borrowing. It’s a five-year note carrying an annual percentage rate of 19%—about the same interest rate as many credit cards—with a fixed monthly payment of $259.41. At the end of five years, the debtor will have repaid the $10,000 loan plus $5,564 in borrowing costs. The latter figure is the total cost of capital.

Compare that with Loan B. Also for $10,000, it’s a six month loan paid down in monthly payments of $1,915.67. The APR is 59%, slightly more than three times the APR of Loan A. Yet the total cost of capital is $1,500, a total cost of capital which is $4,064.33 less than that of Loan A.

Meanwhile, Hoffman notes, the business opting for Loan B is putting the money to work. He proposes the example of an Irish pub in San Francisco where the owner is expecting outsized demand over the upcoming St. Patrick’s Day. In the run-up to the bibulous, March 17 holiday, the pub’s owner contracts for a $10,000 merchant cash advance, agreeing to a $1,000 fee.

Once secured, the money is spent stocking up on Guinness, Harp and Jameson’s Irish whiskey, among other potent potables. To handle the anticipated crush, the proprietor might also hire temporary bartenders.

When St. Patrick’s Day finally rolls around—thanks to the bulked-up inventory and extra help—the barkeep rakes in $100,000 and, soon afterwards, forwards the funding provider a grand total of $11,000 in receivables. The example of the pub-owner’s ability to parlay a short-term financing into a big payday illustrates that “commercial products—where the borrower is looking for a return on investment—are significantly different from consumer loans,” Hoffman says.

SBFA’s Denis observes that financial products like merchant cash advances are structured so that the provider of capital receives a percentage of the business’s daily or weekly receivables. Not only does that not lend itself easily to an annualized rate but, if the food truck, beautician, or apothecary has a bad day at the office, so does the funding provider. “It’s almost like the funding provider is taking a ride” with the customer, says Denis.

SBFA’s Denis observes that financial products like merchant cash advances are structured so that the provider of capital receives a percentage of the business’s daily or weekly receivables. Not only does that not lend itself easily to an annualized rate but, if the food truck, beautician, or apothecary has a bad day at the office, so does the funding provider. “It’s almost like the funding provider is taking a ride” with the customer, says Denis.

Consider a cash advance made to a restaurant, for instance, that needs to remodel in order to retain customers. “An MCA is the purchase of future receivables,” Denis remarks, “and if the restaurant goes out of business— and there are no receivables—you’re out of luck.”

Still, the alternative commercial-lending industry is not speaking with one voice. The Innovative Lending Platform Association—which counts commercial lenders OnDeck, Kabbage and Lendio, among other leading fintech lenders, as members—initially opposed the bill, but then turned “neutral,” reports Scott Stewart, chief executive of ILPA. “We felt there were some problems with the language but are in favor of disclosure,” Stewart says.

The organization would like to see DBO’s final rules resemble the company’s model disclosure initiative, a “capital comparison tool” known as “SMART Box.” SMART is an acronym for Straightforward Metrics Around Rate and Total Cost—which is explained in detail on the organization’s website, onlinelending.org.

But Kabbage, a member of ILPA, appears to have gone its own way. Sam Taussig, head of global policy at Atlanta-based financial technology company Kabbage told deBanked that the company “is happy with the result (of the California law) and is working with DBO on defining the specific terms.”

Others like National Funding, a San Diego-based alternative lender and the sixth-largest alternative-funding provider to small businesses in the U.S., sat out the legislative battle in Sacramento. David Gilbert, founder and president of the company, which boasted $94.5 million in revenues in 2017, says he had no real objection to the legislation. Like everyone else, he is waiting to see what DBO’s rules look like.

“It’s always good to give more rather than less information,” he told deBanked in a telephone interview. “We still don’t know all the details or the format that (DBO officials) want. All we can do is wait. But it doesn’t change this business. After the car business was required to disclose the full cost of motor vehicles,” Gilbert adds, “people still bought cars. There’s nothing here that will hinder us.”

With its panoply of disclosure requirements on business lenders and other providers of financial services, California has broken new legal ground, notes Odinet, the OU law professor, who’s an expert on alternative lending and financial technology. “Not many states or the federal government have gotten involved in the area of small business credit,” he says. “In the past, truth-in-lending laws addressing predatory activities were aimed primarily at consumers.”

The financial-disclosure legislation grew out of a confluence of events: Allegations in the press and from consumer activists of predatory lending, increasing contraction both in the ranks of independent and community banks as well as their growing reluctance to make small-business loans of less than $250,000, and the rise of alternative lenders doing business on the Internet.

In addition, there emerged a consensus that many small businesses have more in common with consumers than with Corporate America. Rather than being managed by savvy and sophisticated entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley with a Stanford pedigree, many small businesses consist of “a man or a woman working out of their van, at a Starbucks, or behind a little desk in their kitchen,” law professor Odinet says. “They may know their business really well, but they’re not really in a position to understand complicated financial terms.”

The average small-business owner belonging to NFIB in California, reports Kabateck, has $350,000 in annual sales and manages from five to nine employees. For this cohort—many of whom are subject to myriad marketing efforts by Internet-based lenders offering products with wildly different terms—the added transparency should prove beneficial. “Unlike big businesses, many of them don’t have the resources to fully understand their financial standing,” Kabateck says. “The last thing they want is to get steeped in more red ink or—even worse—have the wool pulled over their eyes.”

California’s disclosure law is also shaping up as a harbinger—and perhaps even a template—for more states to adopt truth-in-lending laws for small-business borrowers. “California is the 800-lb. gorilla and it could be a model for the rest of the country,” says law professor Hurley. “Just as it has taken the lead on the control of auto emissions and combating climate change, California is taking the lead for the better on financial regulation. Other states may or may not follow.”

California’s disclosure law is also shaping up as a harbinger—and perhaps even a template—for more states to adopt truth-in-lending laws for small-business borrowers. “California is the 800-lb. gorilla and it could be a model for the rest of the country,” says law professor Hurley. “Just as it has taken the lead on the control of auto emissions and combating climate change, California is taking the lead for the better on financial regulation. Other states may or may not follow.”

Reflecting the Golden State’s influence, a truth-in-lending bill with similarities to California’s, known as SB-2262, recently cleared the state senate in the New Jersey Legislature and is on its way to the lower chamber. SBFA’s Denis says that the states of New York and Illinois are also considering versions of a commercial truth-in-lending act.

But the fact that these disclosure laws are emanating out of Democratic states like California, New Jersey, Illinois and New York has more to do with their size and the structure of the states’ Legislatures than whether they are politically liberal or conservative. “The bigger states have fulltime legislators,” Denis notes, “and they also have bigger staffs. That’s what makes them the breeding ground for these things.”

Buried in Appendix B of Treasury’s report on nonbank financials, fintechs and innovation is the recommendation that, to build a 21st century economy, the 50 states should harmonize and modernize their regulatory systems within three years. If the states fail to act, Treasury’s report calls on Congress to take action.

The triumvirate of Hurley, Oxman and Odinet report, meanwhile, that they are forming a task force and, with the tentative blessing of Treasury officials, are volunteering to monitor the states’ progress. “I think we have an opportunity as independent representatives to help state regulators and legislators understand what they can do to promote innovation in financial services,” ETA’s Oxman asserts.

The ETA is a lobbying organization, Oxman acknowledges, but he sees his role—and the task force’s role—as one of reporting and education. He expects to be meeting soon with representatives of the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS), the Washington, D.C.-based organization representing regulators of state chartered banks. It is also the No. 1 regulator of nonbanks and fintechs. “They are the voice of state financial regulators,” Oxman says, “and they would be an important partner in anything we do.”

The ETA is a lobbying organization, Oxman acknowledges, but he sees his role—and the task force’s role—as one of reporting and education. He expects to be meeting soon with representatives of the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS), the Washington, D.C.-based organization representing regulators of state chartered banks. It is also the No. 1 regulator of nonbanks and fintechs. “They are the voice of state financial regulators,” Oxman says, “and they would be an important partner in anything we do.”

Margaret Liu, general counsel at CSBS, had high praise for Treasury’s hard work and seriousness of purpose in compiling its 200-plus page report and lauded the quality of its research and analysis. But Liu noted that the conference was already deeply engaged in a program of its own, which predates Treasury’s report.

Known as “Vision 2020,” the program’s goals, as articulated by Texas Banking Commissioner Charles Cooper, are for state banking regulators to “transform the licensing process, harmonize supervision, engage fintech companies, assist state banking departments, make it easier for banks to provide services to non-banks, and make supervision more efficient for third parties.”

While CSBS has signaled its willingness to cooperate with Treasury, the conference nonetheless remains hostile to the agency’s recommendation, also found in the fintech report, that the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency issue a “special purpose national bank charter” for fintechs. So vehemently opposed are state bank regulators to the idea that in late October the conference joined the New York State Banking Department in re-filing a suit in federal court to enjoin the OCC, which is a division of Treasury, from issuing such a charter.

Among other things, CSBS’s lawsuit charges that “Congress has not granted the OCC authority to award bank charters to nonbanks.”

Previously, a similar lawsuit was tossed out of court because, a judge ruled, the case was not yet “ripe.” Since no special purpose charters had actually been issued, the judge ruled, the legal action was deemed premature. That the conference would again file suit when no fintech has yet applied for a special purpose national bank charter— much less had one approved—is baffling to many in the legal community.

“I suspect the lawsuit won’t go anywhere” because ripeness remains a sticking point, reckons law professor Odinet. “And there’s no charter pending,” he adds, in large part because of the lawsuit. “A lot of people are signing up to go second,” he adds, “but nobody wants to go first.”

Treasury’s recommendation that states harmonize their regulatory systems overseeing fintechs in three years or face Congressional action also seems less than jolting, says Ross K. Baker, a distinguished professor of political science at Rutgers University and an expert on Congress. He told deBanked that the language in Treasury’s document sounded aspirational but lacked any real force.

“Usually,” he says, such as a statement “would be accompanied by incentives to do something. This is a kind of a hopeful urging. But I don’t see any club behind the back,” he went on. “It seems to be a gentle nudging, which of course they (the states) are perfectly able to ignore. It’s desirable and probably good public policy that states should have a nationwide system, but it doesn’t say Congress should provide funds for states to harmonize their laws.

“When the Feds issue a mandate to the states,” Baker added, “they usually accompany it with some kind of sweetener or sanction. For example, in the first energy crisis back in 1973, Congress tied highway funds to the requirement (for states) to lower the speed limit to 55 miles per hour. But in this case, they don’t do either.”

NJ Legislature Aims to Classify Merchant Cash Advance as a Loan in New Disclosure Bill

October 15, 2018 S2262 in New Jersey, a bill to require disclosures in small business lending, was amended this afternoon to define merchant cash advances as small business loans for the purposes of disclosure.

S2262 in New Jersey, a bill to require disclosures in small business lending, was amended this afternoon to define merchant cash advances as small business loans for the purposes of disclosure.

Banks and equipment leasing companies are exempt from the bill.

You can listen to the hearing here. Debate on S2262 begins at the 6 minute, 12 second mark.

The bill’s author (image at right) is Democratic Senator Troy Singleton who represents New Jersey’s 7th legislative district.

Testifying on Monday’s hearing against the bill were Kate Fisher of the Commercial Finance Coalition and PJ Hoffman of the Electronic Transactions Association.

See Post... electronic transactions association (eta), whose members include companies that offer merchant financing, like paypal inc. and amazon.com inc. opposed it, , and lickity split hustled it in a bing bam boom ..voted on approved, , and i am sure just like doofy frank zillions of amendments will be coming down the pipeline, , __, , as stated, , dodd-frank financial reform bill, an 850-page bill that has generated over 2,000 pages of interpretive regulations so far and required “as many as 698 new regulations,” , , , bureaucratic suffocation of mega-bills...the wolf is in the hen house... |

Licensing or Accreditation for sales reps... electronic transactions association for example created their own professional licensing program known as a cpp (certified payment professional). the accreditation must be renewed every 3 years for a price of $350 and with the requirement of additional testing. we are coming up on the first 3 year anniversary since the accreditation came into existence and some are calling it a failure. , , the gripe seems to be focused around the argument that merchants don't know what a cpp is so being one or not being ... |

DailyFunder Issue 4 Sneak Peek... electronic transactions association, noah breslow, ceo of ondeck capital, jeremy brown, ceo of rapidadvance, tom mcgovern, vp of cypress associates, rohit arora, ceo of biz2credit, zhengyuan lu, svp of ondeck capital, eric rapp, svp of dbrs, chuck weilamann, svp of dbrs, simon lobanov, ceo of red payments, chance barnett, ceo of crowdfunder, barney frank, former congressman and key author of the dodd-frank wall street reform act, , , plus there are plenty of other goodies!, , if you have not gotten a hard copy of the magazine in the past and want to start getting them, email me at sean@dailyfunder.com. if you're interested in advertising or in being a source for a future story, ... |