Legal Briefs

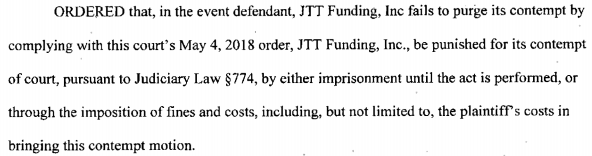

ISO Pretending to be Funder May Be Sent to Jail

October 14, 2018A New York Supreme Court judge ordered on Thursday that Long Island-based ISO JTT Funding either be fined or sent to prison if it does not comply with a previous restraining order obtained by NYC-based funder Accel Capital.

Accel alleges that JTT funding has been impersonating it through correspondence and on contracts, a scheme that was outed when merchants claimed they had been duped into sending thousands of dollars upfront to JTT (disguised as Accel) to obtain a loan yet never received one. Accel responded by suing JTT and obtained a restraining order on default when the defendant failed to respond.

According to the Financial Times, JTT Funding is owned by Queens-born mixed martial arts fighter Jim “The Tyrant” Boudourakis. In his October 2017 interview with the publication, Boudourakis said, “There was a learning curve, going from being a fighter to a salesman. But I’m good with people.” FT also reported that his company had 18 full-time salespeople and was funding $4 – $5 million per month.

In an unrelated suit, JTT Funding is accused of forging a confession of judgment.

The Accel Capital suit can be found in the New York Supreme Court under Index Number: 153447/2018

Capital Stack Hit With Class Action Lawsuit

October 10, 2018A class action lawsuit brought by former employees of Capital Stack, LLC was filed in federal court on Tuesday for damages resulting from alleged labor law violations. David Rubin, Brian Stulman, eProdigy ACH, LLC, and eProdigy Operations, LLC are also among the named defendants. Capital Stack is a merchant cash advance company based in New York.

The 22-page complaint lays out seven claims including failure to pay the minimum wage required by New York Labor Law.

The suit can be downloaded here.

The case is 1:18-cv-09230 in New York Southern District Court.

Renaud Laplanche Barred From the Securities Industry

September 28, 2018

The SEC announced today that it charged LendingClub Asset Management, formerly known as LendingClub Advisors LLC (LCA), and its former president and co-founder Renaud Laplanche, with fraud – for improperly using fund money to benefit LendingClub Corporation, LCA’s parent company. LCA, Laplanche and Carrie Dolan, LCA’s former CFO, also were charged with improperly adjusting fund returns.

LCA, Laplanche and Dolan have agreed to settle the SEC’s charges against them and will pay penalties of $4 million, $200,000, and $65,000, respectively. The SEC also barred Laplanche from the securities industry for three years. LCA, Laplanche, and Dolan agreed to the entry of the SEC’s order without admitting or denying the agency’s findings.

This follows Laplanche’s ouster from LendingClub in May 2016 amid revelations of falsified loan records and conflicts of interest under Laplanche’s leadership. He is now the CEO of Upgrade, a San Francisco-based online lender, and he has been hailed recently for his resilience for making such a quick comeback.

A representative from Upgrade provided deBanked with a statement from Laplanche:

“I am pleased to have worked out a settlement with the SEC to put to rest any issues related to compliance lapses that might have occurred under my watch at Lending Club. Consistent with SEC policy, I have agreed not to admit nor deny the specific narrative of the events contained in the settlement order. I would like, however, to provide additional context:

1. To the extent there was an imbalance between 60-month and 36-month loans in one of the LCA funds as compared to its initial target, the specific 36/60-month balance was disclosed to investors every month.

2. Any manual adjustments used by the LCA team as part of the funds valuation methodology had a total net impact of 0.08% of the funds value over 5 years, and I strongly believe those adjustments were made by the LCA team in good faith.

In any event, I am glad that we can now put these issues behind us and focus on the important goals of making credit more affordable to consumers and delivering attractive returns to investors through disciplined underwriting and exciting product innovation. With the benefit of my prior experience, I feel better equipped to establish a strong culture of compliance and effective internal controls under the supervision of capable professionals.”

LendingClub, the actual company, or LendingClub Corporation, was spared any charges from the SEC because of its cooperation with the agency. The SEC press release explains below:

“The SEC’s Enforcement Division determined not to recommend charges against LendingClub Corporation, which promptly self-reported its executives’ misconduct following a review initiated by its board of directors, thoroughly remediated, and provided extraordinary cooperation with the agency’s investigation. LCA also reimbursed approximately $1 million to investors who were adversely impacted by the improperly adjusted monthly returns.”

Lending Club, which Laplanche brought public 2014, did not respond in time to questions before publication.

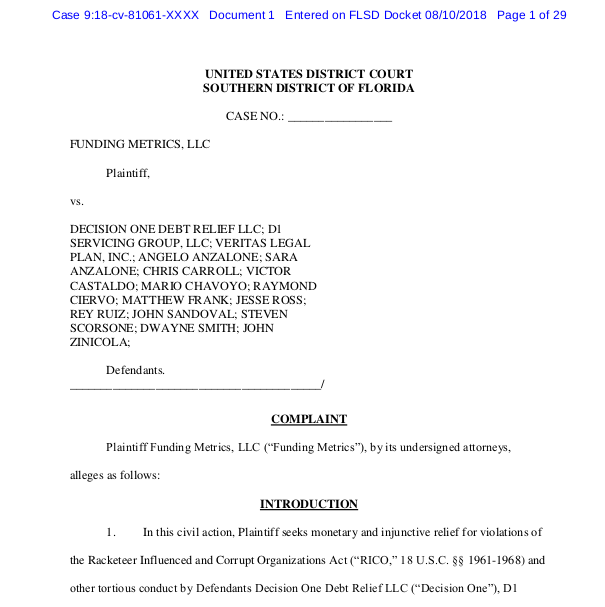

War on Debt Settlement Continues: 16 Defendants Sued in RICO Case

September 6, 2018

Fourteen individuals and two companies (including Decision One Debt Relief) were sued by Funding Metrics in Federal court last month for allegedly “conducting a nationwide illegal debt restructuring scheme through numerous acts of mail and wire fraud.”

The suit, which stems from the defendants’ interference with Funding Metrics’ merchant cash advance customers, makes six claims, among them financial damages resulting from state and federal crimes. Per the complaint:

“Defendant Decision One (along with its affiliate/alter ego D1 Servicing) fraudulently presents itself as being able to renegotiate and restructure merchant agreements with Plaintiff and other funding companies. It has established a deceptive business practice of making misleading and often outright false representations to merchants under contract with Plaintiff promising that, with its help, these merchants will save money on those contracts by defaulting on them. Decision One tells merchants that they can safely stop paying cash advance funding companies like Plaintiff; that it will go to work for them promptly; that it can reduce their debt by 60-80% or more; and that they will be provided with a Veritas insurance plan to cover legal expenses arising from their defaults, once cash advance companies exercise their rights under agreements with their merchants, as they inevitably will. Based on these misrepresentations, the merchants default on their contracts with their funders – that is, at Decision One’s direction, they stop paying their funders and instead pay Decision One – although Decision One does not even expect to achieve results for the merchants. The result is a fraud on the merchants and tortious interference with the contracts Plaintiff have with them.”

The suit is just the latest bomb dropped on the exploding debt settlement industry. deBanked began covering the controversy surrounding debt settlement in late 2016 after the owner and employees of an upstate New York debt settlement company were arrested for charging merchants to restructure their merchant cash advances and then not actually performing any services. The owner, Sergiy Bezrukov, was charged with money laundering, bank fraud, mail fraud, wire fraud and conspiracy to defraud. Bezrukov has been locked away in jail for almost two years awaiting trial. He is facing a maximum of 30 years. Two of his employees pled guilty, Vanessa Cardona to bank fraud and Dustin Walker to conspiracy to commit bank fraud.

Since then, nearly a dozen major lawsuits have been filed by merchant cash advance companies against other debt settlement companies that are alleged to be carrying out similar schemes. One of those sued companies, NJ-based Corporate Bailout LLC, was featured on the cover of the New York Post last summer for being “the craziest office in America.” Corporate Bailout was sued by both Yellowstone Capital and Everest Business Funding which later resulted in a very public settlement agreement that forced Corporate Bailout to fork over $500,000 to the two MCA companies.

Decision One Debt Relief, sued now by Funding Metrics, was also originally a co-defendant alongside MCA Helpline in a lawsuit filed by Everest Business Funding earlier this year. In February, after determining the two were not related, Everest dropped the claims against Decision One only. The suit against MCA Helpline is still pending.

Around that same time, a representative for Decision One revealed to deBanked that the company was on track to be doing more than $100 million a year in business.

Bezrukov, by contrast, who currently resides in a Niagara County New York jail, is accused of having only obtained $1.2 million throughout his entire debt settlement venture’s existence. Although Decision One is not being charged criminally, the private civil suit alleges damages caused by a violation of criminal statutes including RICO.

The Funding Metrics suit against Decision One was filed in the Southern District of Florida under ID# 9:18-cv-81061.

1 Global Capital Charged With Fraud by SEC

August 29, 2018

The Securities & Exchange Commission unsealed a 10-count complaint against 1 Global Capital LLC (“1st Global Capital”), its owner Carl Ruderman, and related parties on Wednesday.

The South Florida firm “fraudulently raised more than $287 million from more than 3,400 investors to fund its business offering short-term financing to small and medium-size businesses,” the complaint begins.

Investors were offered low-risk, high-return investments that 1st Global would use to fund merchant cash advance deals. Ruderman, who owned the company through a trust, misappropriated $35 million of the funds, paying a lot of it to himself and companies he controlled that had nothing to do with MCA, the SEC alleges. Beyond that, millions more went towards other pet projects like a $50 million purchase of distressed credit card debt.

But the deception went deep, the complaint lays out. 1st Global touted a default rate of only 4% despite the fact that 15-18% of their deals over the last 2 years had resulted in collections lawsuits.

By October 2017, the statements investors received showing their monthly performance were faked with the value and performance significantly inflated. By June 2018, one line item on monthly statements (labeled “cash not deployed”) reported that investors collectively had $70 million in idle cash ready to be put into deals. Meanwhile, the company itself only had about $20 million in all of its bank accounts combined, money that was being used for everything including operating expenses, salaries, and commissions.

1st Global’s alleged auditor, Daszkal Bolton, LLP, says they never audited 1st Global’s statements and haven’t had anything to do with the company since 2016. Nonetheless, 1st Global placed Daszkal Bolton’s name on statements given to investors and stated on their website that investor balances were validated by an accounting firm quarterly.

MCA Companies Have Won a “Sh*t Ton” of Cases, Judge Declares

August 27, 2018 A judge in Buffalo, New York has finally had enough with merchants trying to claim that merchant cash advances are loans.

A judge in Buffalo, New York has finally had enough with merchants trying to claim that merchant cash advances are loans.

At issue were defendants who sought to overturn a confession of judgment filed by SOS Capital. The Honorable Catherine Nugent Panepinto, who presided over the case, didn’t like that one bit, but what was more offensive to her was the manner in which the defendants tried to overturn it.

With a shit ton of case law already weighing against the defendants for filing an improper motion, Judge Nugent Panepinto went a step further by reminding the defendants that there is no merit to the argument that the subject merchant agreement was a loan.

The defendants, who seemed completely doomed to pay SOS Capital’s attorney fees, were saved only by the charm of their affable Long Island attorney.

This case was decided in Erie County, NY under Index #803512/2018.

Two Commercial Finance Consultants Charged By SEC in Ponzi Scheme

August 22, 2018Two commercial finance consultants were charged by the SEC earlier this week for their alleged role in soliciting investors to place their savings into mortgage-backed securities issued by Woodbridge Group of Companies, LLC, a company revealed to be a $1.2 billion ponzi scheme.

Barry Kornfeld and Ferne Kornfeld of Parkland, Florida, allegedly earned $3.7 million in commissions by selling unregistered securities to more than 500 investors. Barry Kornfeld was already barred by the SEC for previous securities violations, the complaint states. The Kornfelds taught a “conservative retirement, income planning and social security” class at Florida Atlantic University, where the investments were pitched, the SEC says.

FEK Enterprises, Inc. DBA First Financial Tax Group, the company the Kornfeld’s operated, is also named in the complaint.

Their LinkedIn profiles, however, currently list them as the owners of Value Capital Funding, a small business financing broker in Boca Raton, FL.

Merchant Cash Advance Company Wins in Bankruptcy Court After Judge Rules It’s an Ordinary Part of Business

August 21, 2018 Last week, a bankruptcy judge in the Northern District of Illinois ruled that a merchant had used so many merchant cash advances that it had become a normal part of their business.

Last week, a bankruptcy judge in the Northern District of Illinois ruled that a merchant had used so many merchant cash advances that it had become a normal part of their business.

At issue was Network Salon Services, a business founded in 2004 that was brought back from the brink of insolvency in January 2013 by a merchant cash advance. That advance, coupled with dozens of advances from more than 14 MCA companies over the following 3 and a half years would keep Network Salon on life support until it finally failed for good.

At the end, Network Salon had just $200 to its name and nearly $4 million in outstanding future receivables due to MCA companies.

After the Chapter 7 proceedings commenced, the bankruptcy trustee came knocking on the doors of several MCA companies to give back the funds it believed had been fraudulently transferred and obtained through criminally usurious means.

One of those companies, NY-based LG Funding, pushed back hard, and on August 15th the judge ruled in LG’s favor. In a carefully considered decision, The Honorable Jacqueline Cox said that an exception applied to LG Funding. Unlike a normal creditor where certain property obtained leading up to a bankruptcy becomes returnable to the trustee, Network Salon relied on MCAs in its normal course of business for years and thus the transfers of funds to LG Funding was the ordinary course of business not subject to return.

So ordinary was it in fact that Network Salon used MCAs to make payments on other MCAs, going so far that at one point one of its bank accounts showed no deposit activity for a month except for deposits from MCA companies and online lenders.

Ultimately it didn’t matter if LG Funding was actually debiting the deposits made by rival companies rather than the actual proceeds of sales, Judge Cox opined, because this deviation from the contract was not fraudulent and both parties benefited from it.

The usury arguments, as usual, failed, because New York courts (The state governing LG Funding’s contracts) have already determined that MCA transactions are not loans and therefore can’t be usurious.

“The Trustee has failed to meet her burden to establish by a preponderance of the evidence that the transfers were preferential or constructively fraudulent and therefore subject to avoidance,” The judge ordered. “LG Funding has succeeded in establishing that the transfers were made in the ordinary course of business, defeating the Trustee’s 547(b) preference claim. The constructive fraudulent conveyance claim fails because Network Salon received reasonably equivalent value in the transactions in issue. Judgment will be entered in favor of Defendant LG Funding on all counts.”

This post is an oversimplified explanation. Download the 24-page decision HERE for the full facts and details.