Crowdfunding

How Ireland’s Spark Crowdfunding Got its Start

October 5, 2019 “We’ve not invented anything new,” Chris Burge, CEO of Spark Crowdfunding, tells me. “We saw the rise of crowdfunding in Europe, the states, and the world and we thought, ‘well why doesn’t Ireland have one?’”

“We’ve not invented anything new,” Chris Burge, CEO of Spark Crowdfunding, tells me. “We saw the rise of crowdfunding in Europe, the states, and the world and we thought, ‘well why doesn’t Ireland have one?’”

We’re in the lobby of a Dublin hotel drinking coffee, right around the corner from Spark’s offices on South William Street. There are at least three other professional meetings going on over variations of hot drinks, the room serving as a haven from the uniquely cold-yet-clammy weather outside.

Burge tells me about how he came to be in alternative finance. An engineer by trade, Burge entered the field after both him and his business partner had found the traditional process of investing to be wanting. “Both of us had invested in the past and had found it cumbersome, long-winded, and expensive,” leading them to explore more accessible, less unwieldy options.

Thus, from such a hole in the market sprung Spark Crowdfunding. Offering equity investment options from as low as €100, Burge sought to streamline the investment by offering it via an online platform from which members can view pitch videos, pitch decks, and detailed documents.

Established in early 2018, the company saw its first big success in August of that year with Fleet, an Irish business that allows cars owners to rent their vehicles to the public from their driveways as well as gas stations. Asking for €275,000, Fleet received this and more, with the total amount invested reaching €385,000.

Established in early 2018, the company saw its first big success in August of that year with Fleet, an Irish business that allows cars owners to rent their vehicles to the public from their driveways as well as gas stations. Asking for €275,000, Fleet received this and more, with the total amount invested reaching €385,000.

Allowing for choice when deciding which investors to choose from and how much to take from who, Burge says that flexibility is key to their platform and likens it to Dragons’ Den with much more than five potential investors.

And with bank loans for small businesses becoming increasingly more difficult to access, Spark is positioned similarly to crowdfunding in the US. “Where a company would have previously gone to Allied Irish Bank or Bank of Ireland to borrow €100,000 in order to get their business off the ground, they’re now finding it very difficult and nigh impossible as well to get these loans, so we found that a lot of companies are coming to us to do this.” In addition to such an investment, startups in Ireland may receive extra funding from Enterprise Ireland, a government organization that provides aid to indigenous businesses and will match investments up to a point so long as the company meets certain requirements.

Accompany this with the lack of regulation in the crowdfunding space in Ireland and it would appear that the industry is set to expand.

And on the topic of expansion, Burge is keeping most of his cards to himself. “We know that Ireland is a small country compared to the rest of Europe, or compared to the rest of the world, so there’s a limited amount of stuff that we can do here, and so do we want to grow? Yes. Are we going to go to the states? Probably not. But the rest of Europe? Yes, absolutely. Have we picked out a few countries? Yes, we have.”

Crowdfunding Legal Limit Too Low for Intended Beneficiaries

July 25, 2018 Regulation Crowdfunding (Reg CF), a regulation that grew out of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act of 2012, was designed to allow non-accredited investors to invest relatively small amounts in startups. But the regulation seems not to be serving its purpose, according to people in the fintech investment community.

Regulation Crowdfunding (Reg CF), a regulation that grew out of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act of 2012, was designed to allow non-accredited investors to invest relatively small amounts in startups. But the regulation seems not to be serving its purpose, according to people in the fintech investment community.

Why is this? Because the maximum amount that can be raised in a single year under Reg CF is limited to $1,070,000.

“I’ve had clients consider [using] Reg CF, but when they see that they can only raise $1 million, they say it’s not worth the trouble,” said James P. Dowd, CEO of North Capital, a Salt Lake City-based broker-dealer that helps private companies raise money.

“I’m not anti-regulation at all, but if the reward is not there, people won’t go through the trouble,” Dowd said. “Let’s have regulations that are appropriate for the need.”

Dowd said that a small startup seeking funding for a series A round is typically looking to raise around $10 million. The $1.07 million cap for Reg CF is therefore inadequate. A startup’s other options for raising money under the JOBS Act include regulations D, S and A+. Dowd said that Reg D is the most common. It involves very little paperwork and is less expensive compared to other options. Reg S applies only to offshore investors and Reg A+ makes sense only if the startup is looking to raise $20 million or more because this option is costly to file.

All of these options require that investors be accredited, which translates to investors being wealthy. (Accredited investors must have a net worth of at least $1,000,000, excluding the value of one’s primary residence). On the other hand, if an entrepreneur opts to raise money through a Reg CF, investors need not be accredited, although there are still restrictions on how much they can invest, given their income.

Reg CF allows entrepreneurs to access a wider pool of investors. And Dowd, along with others in the investment community, believe that the current $1.07 million annual cap should be raised to as high as $20 million to satisfy the need of entrepreneurs who are looking to raise more money.

“The infrastructure for the crowdfunding industry has been tested and is ready to expand,” said Douglas S. Ellenoff, partner at Ellenoff Grossman & Schole who is an expert on crowdfunding.

Ellenoff said that there was much fear among regulators following the 2012 JOBS Act that crowdfunding would be ripe for fraud. But the fraud didn’t happen. He believes in raising the Reg CF cap to allow the crowdfunding industry to mature. And he believes that once the cap is raised, more substantial companies will start to use crowdfunding which further legitimate it as a valid way of raising money.

North Capital was founded by Dowd in 2008 and provides an array of financial advisory services to its clients. In addition to its Salt Lake City headquarters, it also has offices in Benicia, California and McAllen, Texas.

Equity Crowdfunding to Masses Slow Out of the Gate, But Pickup Expected

February 25, 2017

After a lackluster start, spectators are betting on more promising times ahead for equity crowdfunding to the masses.

Although it’s been talked about for years, it wasn’t until last May that the general public could buy shares of their favorite companies through equity crowdfunding. Before then, only accredited investors could be part of the crowd.

The new crowdfunding regulation, known as Reg CF, has been talked about for several years as a potential game-changer for small businesses seeking growth capital. But so far, it hasn’t gotten the fast-track reception that some industry watchers had hoped for. Between inception and January 16 of this year, 75 companies have run successful equity crowdfunding campaigns, raising $19.2 million, according to statistics compiled by Wefunder, an online funding portal for equity crowdfunding.

Even so, industry watchers aren’t discouraged, saying it takes time for any new product to catch on and to gain traction.

“Equity crowdfunding is in its infancy. It’s got to be a toddler before it can be a teenager, and it’s got to be a teenager before it can be grown up. I think in three to five years, equity crowdfunding will be all grown up,” says Kendall Almerico, a partner with the law firm DiMuroGinsberg in Washington, who represents numerous clients in Jobs Act-related offerings.

A YEAR OF TRIAL AND ERROR

Some industry watchers had hoped equity crowdfunding to the general public would take off immediately, on the heels of successful rewards-based crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo. Consider that since Kickstarter launched on April 28, 2009, 12 million people have backed a project, $2.8 billion has been pledged, and 118,362 projects have been successfully funded, according to company statistics from Jan. 16.

People looked at Kickstarter’s accomplishments and projected that from day one, equity crowdfunding to the public would be an immediate success, Almerico explains.

Instead, Almerico says 2016 was a year of trial and error, in which companies seeking equity funding tested out the market and learned the process. Initially, there were several funding failures, where companies set fundraising goals that were too lofty and came away with nothing. Other companies have been hesitant to dip their toes into a market that’s still very new and unchartered.

“I’m not surprised that it has taken a little bit of time for companies to raise money this way,” Almerico says.

However, industry participants say that every success story encourages others and the market will continue to build on itself.

“We are very optimistic that 2017 will be the year it goes more mainstream in the U.S,” says Nick Tommarello, founder and chief executive of Wefunder, who expects crowdfunding levels in 2017 to reach three to four times what they were at the end of 2016.

WADING THROUGH UNCHARTERED TERRITORY

Certainly, Reg CF is still very new in practice. On October 30, 2015, the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted final rules to permit companies to offer and sell securities through equity crowdfunding for non-accredited investors. But it wasn’t until May 16, 2016 that this new type of investing actually became permissible.

Companies that want to raise money from the general public have to do it through a funding portal that is registered with the SEC. As of mid-January, there were 21 funding portals, according to a listing on Finra’s website. The bulk of the funding thus far has come through the portals Wefunder, StartEngine and NextSeed, according to statistics compiled by Wefunder. Indiegogo, best known as a leader in perks-based crowdfunding, has also gotten a fair amount of business. Indiegogo launched an equity crowdfunding portal late last year through a joint venture with MicroVentures, an online investment bank.

There are significant rules when it comes to members of the general public investing in equity deals; how much you can invest per year depends on your net worth or income. Everyone can invest at least $2,000, and no one may invest more than $100,000 per year, according to SEC rules.

Meanwhile, companies are limited to raising $1 million in a 12-month period using Reg CF. Also, they must raise enough to hit their funding target or the fundraising round is a bust. They can, however, use other avenues to raise money simultaneously, such as through accredited investors or venture capitalists. This can be an advantage for companies because it allows them to tap their customer base—a great marketing and customer-retention tool—and yet still seek growth financing from investors with deeper pockets.

Over time, as equity crowdfunding gains traction, Almerico predicts the SEC and Congress will revisit some of the regulations and tinker with the laws to make them even more user friendly. And that too, will help crowdfunding gain ground with investors and companies, he says.

For instance, under current rules, a company can’t market its offering until it goes live, at which point additional marketing restrictions set in. Congress and the SEC will likely change some of these restrictions to make the rules more similar to Regulation A, which covers offerings of larger sizes, Almerico says.

A CONSUMER-FACING PROPOSITION

For the most part, companies that are consumer-facing as opposed to B2B will have the most luck with equity crowdfunding. For one thing, consumer-facing companies often have an easier time explaining their story to the public. Also, there’s real benefit for consumer based businesses to get their customers to sink money not only into a company’s product, but behind the scenes as well. Thus far companies that have sought funding under Reg CF run the gamut from breweries to tech startups, Wefunder data shows.

When it comes to equity crowding, investment levels tend to be small. Wefunder stats shows that 31 percent of investments made through its own platform are $100 and 76 percent of investments are under $500. “The whole point is to have lots of investors investing small amounts of money and together they add up,” Tommarello explains.

One of Wefunder’s largest offerings was Hops and Grain Brewing, a microbrewery based in Austin, Texas. The company is one of three businesses to raise $1 million on Wefunder, and more than 70 percent of the money came from its own customers, according to Tommarello. “Equity crowdfunding allows customers an opportunity to back things they really care about and it’s great marketing for the company too,” he says.

Another company, Snapwire Media Inc., a start-up in Santa Barbara, California, also believes in the power of the crowd to raise funds and gain marketing traction. Chad Newell, the company’s chief executive, says Snapwire wasn’t at a point where it felt ready to solicit venture capital money, but felt confident that its users, who were already passionate about its services, would become their biggest advocates.

The company, which connects a new generation of photographers with businesses and brands that need on-demand creative imagery, was launched in 2014. It previously raised $2 million from accredited investors before raising $179,065 from the general public on the funding portal StartEngine. In December 2016, the company launched a campaign to raise additional funds on Wefunder.

“Because we had a strong community and such a large one, we felt it was a good way to raise funds. Why not raise it from the people that care about the product the most?” Newell says.

OVERCOMING THE HURDLES OF NEWNESS

Because equity crowdfunding to the general public is so new, there’s still a lot of uncertainty about how the process works—both among companies looking to raise money and potential investors.

“The biggest hurdle today is that equity crowdfunding is still underground versus rewards-based crowdfunding,” says Howard Marks, co-founder and chief executive of the online portal StartEngine. “It’s tiny. It’s small. It’s nothing. It’s not even a dot in the grand scheme of things,” he says.

At this point, many people still don’t realize they can invest, or how to invest. He likens equity crowdfunding to index funds or junk bonds that were once completely unknown products. Over the years, however, they gained broad acceptance and are now widely used investment vehicles. “Every time there’s a new financial product that comes out, it takes time,” he says.

At this point, many people still don’t realize they can invest, or how to invest. He likens equity crowdfunding to index funds or junk bonds that were once completely unknown products. Over the years, however, they gained broad acceptance and are now widely used investment vehicles. “Every time there’s a new financial product that comes out, it takes time,” he says.

In December, five new companies used StartEngine for equity crowdfunding. In January, he expects there to be more than 10. By the middle of next year, he predicts there could be 20 a month, and in two years from now he’s hopeful to be doing about 500 equity deals a month.

“Within five years, our plan is to have 5,000 companies on the platform,” he says. “The demand for capital is pretty large.”

At this point, Wefunder is the largest platform for Reg CF offerings in terms of dollars funded, successful offerings and number of investors.

According to data through January 16, forty-six of the seventy-one companies that listed on its platform, or 65 percent, had successful offerings, meaning they reached their investment goals.

Some funding portals have felt the pangs of being new to the industry and are trying to get their bearings to compete more effectively.

Vincent Petrescu, chief executive of truCrowd Inc, a funding portal based in Chicago, says his company got registered in May 2016 and spent the rest of the year learning the lay of the land. Ultimately, truCrowd decided it would be better off specializing in a few verticals than going after all types of companies. Its plan now is to focus on the cannabis industry and the HR space.

“I think that the potential is huge. There are lots of good companies out there that need capital,” he says.

THE SNOWBALL EFFECT

Wefunder data shows that investors who buy into one deal tend to do another deal shortly after, so it’s a compounding effect, Tommarello says. “It’s a snowball rolling down a hill. We’re developing a whole new class of mini angel investors,” he says.

In terms of future growth, Petrescu of truCrowd says the biggest hurdle for the industry is exposure. Lots of people still don’t know about it, and they are still in the mindset that it’s illegal because it was for so long.

He says he’s not too concerned, though, because the UK had a similar experience when equity crowdfunding to the general public first started there a few years back. As soon as the success stories start to become more publicized and people see the returns that are possible, he predicts interest will grow. “The potential is there. No doubt about it,” he says.

For companies that are giving more thought to equity crowdfunding, it may help to seek out advice from others that have already traveled this road. Newell of Snapwire says he gets calls every week from company founders to ask about his experience with equity crowdfunding and to discuss in further detail whether it might be the right option for them.

Newell tells companies that ask him about equity crowdfunding that it’s an effective way to raise funds, with certain caveats. For instance, you really have to understand the rules of what you’re allowed to do and what you can’t do because there are many more restrictions when marketing to the general public versus accredited investors. You also have to be good at marketing—or hire a company to do it on your behalf—and have a sizable group of users that you think will want to invest in your future.

“It’s been a great source of capital for Snapwire because of our passionate community. I caution any company that doesn’t have a large community to be careful about spending time and resources and have realistic expectations,” he says.

He also says companies should have realistic fundraising goals since it is unusual—at least at this juncture—to raise a million dollars from small investors through equity crowdfunding. It’s more realistic to expect to raise $200,000 to $500,000, he says.

“I think everyone gets attracted to the top number. But that’s not necessarily what happens. Equity crowdfunding should be complementary to any funding strategy. By itself, it’s not some magic bullet,” he says.

Meet the Lending Platform With 0% Interest (Kiva)

January 6, 2016 Chany of Angela’s Boutique in Philadelphia, PA needs $5,000 to help purchase new signage and lighting to improve her storefront. She’s been turned down by banks even though she’s been in business for more than five years. 61 participants have already contributed to her loan thanks to a marketplace lending platform, which puts her very close to her goal. If it funds, all of the participants will get back their principal from her payments over the next 24 months and NO interest.

Chany of Angela’s Boutique in Philadelphia, PA needs $5,000 to help purchase new signage and lighting to improve her storefront. She’s been turned down by banks even though she’s been in business for more than five years. 61 participants have already contributed to her loan thanks to a marketplace lending platform, which puts her very close to her goal. If it funds, all of the participants will get back their principal from her payments over the next 24 months and NO interest.

Meet Kiva Zip, the anti-Lending Club because the borrowers are far from anonymous and the yield delivered to investors is negative due to inflation.

Angela’s Boutique, which is a real prospect on the Kiva Zip platform, includes a picture of the owner, her bio, endorsements, and comments from supporters.

According to Jessica Feingold, Kiva’s East Coast Manager of Development, “Kiva is the world’s first and largest crowdfunding platform for social good with a mission to connect people through lending to alleviate poverty and expand economic opportunity.”

And just like Lending Club, contributions as small as $25 are accepted. Obviously structured as a non-profit, “Kiva and its growing global community of 1.2 million lenders has crowdfunded more than $775 million in microloans to over 1.7 million entrepreneurs in 83 countries, all the while maintaining a 98% repayment rate,” according to Feingold.

Normally thought of as an overseas endeavor, Feingold said that “in 2011, Kiva launched Kiva Zip, a pilot program in the US that provides 0% interest crowdfunded loans to small business entrepreneurs.” Their underlying purpose and target market sounds very much like those being served by for-profit alternative lenders. “Kiva doesn’t require a minimum FICO score, collateral, or a minimum operations period for the business,” Feingold said.

Since inception they’ve made loans to over 1,800 borrowers in 47 days states, Peru, and Guam.

Notably, Lending Club promises borrowers that their “identity will at all times remain confidential and not be disclosed to anyone,” according to their website. Kiva by contrast is looking to “instill empathy” in their lenders. “We want to show that whether in East New York or Uganda, underserved entrepreneurs are credit-worthy, and will pay you back,” Feingold said. “All of these features on the Kiva websites enhance our ability to do so.”

While there is definitely a certain allure about being able to see the borrower for yourself, the concept seems to fly in the face of Dodd-Frank’s Section 1071 which stipulated that lenders are prohibited from knowing the sex and gender of business loan applicants. While the CFPB is not currently enforcing the law until the rules can be clarified, Democratic members of Congress have been pushing them to take action.

While there is definitely a certain allure about being able to see the borrower for yourself, the concept seems to fly in the face of Dodd-Frank’s Section 1071 which stipulated that lenders are prohibited from knowing the sex and gender of business loan applicants. While the CFPB is not currently enforcing the law until the rules can be clarified, Democratic members of Congress have been pushing them to take action.

According to the law, no loan underwriter or other officer or employee of a financial institution, or any affiliate of a financial institution, involved in making any determination concerning an application for credit shall have access to any information provided by the applicant about whether or not the business is women-owned or minority owned.

As small businesses often celebrate the heritage of their founders, and at times that can be the entire reason customers buy from them in the first place, the law has presumably put the small business lending world in an awkward position (and that’s why the law should be repealed). Non-profits like Kiva have embraced the very things that make a small business bankable outside of a credit score, like the owner, their background, and their story.

Borrowers on the Kiva Zip platform don’t raise all the money from strangers though. Their credit-worthiness is based on their ability to recruit friends and family to fund a small portion of their loan. The other lenders though of course may make their decisions based on the numbers or entirely on the perceived cultural, racial, or gender values of the borrower, all of the things that the CFPB is attempting to eradicate in the for-profit arena.

I didn’t ask Kiva any questions about Dodd Frank or Section 1071, but many people might empathize with their empathy approach as a way to fund small businesses that otherwise don’t qualify for bank loans. Its reminiscent of the subjective underwriting that a lot of alternative lenders and merchant cash advance companies employ to get deals done that banks won’t touch.

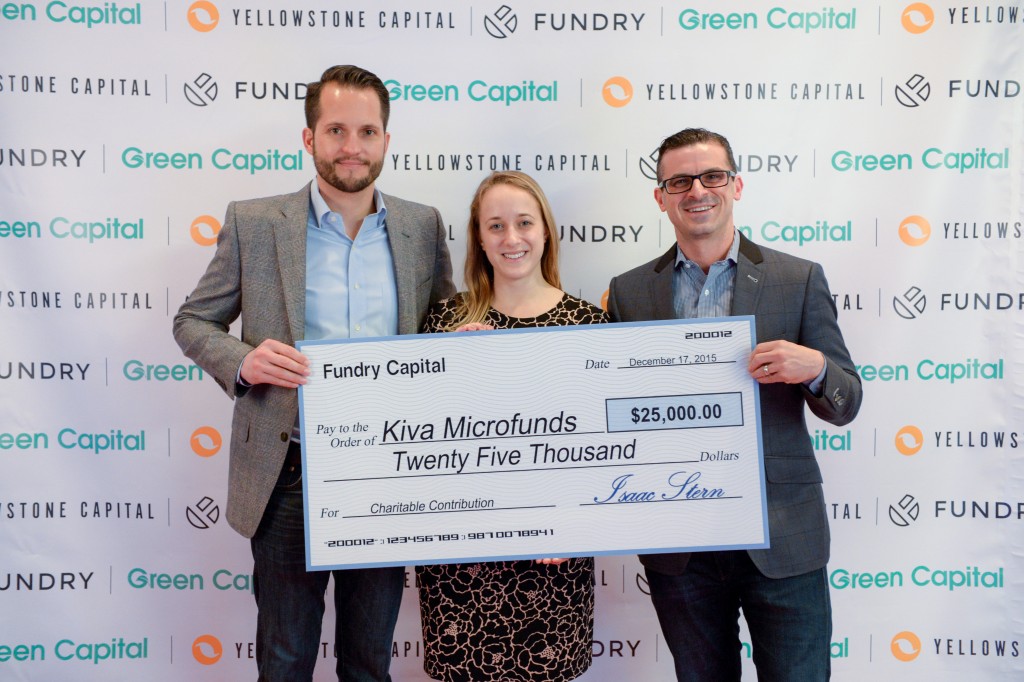

Not so coincidentally, Fundry, Yellowstone Capital’s parent company, donated $25,000 to Kiva just last month to support their cause.

Kiva’s Feingold (pictured at center above) said in regards to that, “Kiva is thrilled to receive a grant from Fundry to further our work to make credit more affordable.”

Have you heard? Banks aren’t lending. Nobody at LendIt seems to mind though. Ron Suber, the President of Prosper Marketplace, said earlier today that banks are not the competition. That’s an interesting theory to digest when contemplating the future of alternative lending. If banks are not the competition, then who is everyone at LendIt competing against? I think the obvious answer is each other, but much deeper than that, the competition is the traditional mindset of borrowers.

Have you heard? Banks aren’t lending. Nobody at LendIt seems to mind though. Ron Suber, the President of Prosper Marketplace, said earlier today that banks are not the competition. That’s an interesting theory to digest when contemplating the future of alternative lending. If banks are not the competition, then who is everyone at LendIt competing against? I think the obvious answer is each other, but much deeper than that, the competition is the traditional mindset of borrowers.

You might not have known this, but one of the most lucrative opportunities in merchant cash advance is the ability to participate in deals. It’s a phenomenon Paul A. Rianda, Esq addressed in DailyFunder’s March/April issue with his piece,

You might not have known this, but one of the most lucrative opportunities in merchant cash advance is the ability to participate in deals. It’s a phenomenon Paul A. Rianda, Esq addressed in DailyFunder’s March/April issue with his piece,  That’s the interesting twist about crowdfunding in the merchant cash advance industry. You can’t get in on it unless you know somebody. There are no online exchanges for anonymous investors to sign up and pay in. It requires back door meetings, contracts, and typically advice from sound legal counsel. A certain level of business acumen and financial prowess are needed to be considered. These transactions are fraught with risk.

That’s the interesting twist about crowdfunding in the merchant cash advance industry. You can’t get in on it unless you know somebody. There are no online exchanges for anonymous investors to sign up and pay in. It requires back door meetings, contracts, and typically advice from sound legal counsel. A certain level of business acumen and financial prowess are needed to be considered. These transactions are fraught with risk.  I’d like to think that the term, merchant cash advance, is mainstream enough that a congressman would know what it was. I have no idea if that’s the case though. What I do know is that Renaud Laplanche, the CEO of Lending Club gave testimony before the Committee on Small Business of the United States House of Representatives on December 5, 2013.

I’d like to think that the term, merchant cash advance, is mainstream enough that a congressman would know what it was. I have no idea if that’s the case though. What I do know is that Renaud Laplanche, the CEO of Lending Club gave testimony before the Committee on Small Business of the United States House of Representatives on December 5, 2013. If I were to offer you the choice between a free DVD with a retail value of $20 or a free $20 bill, which one would you take?

If I were to offer you the choice between a free DVD with a retail value of $20 or a free $20 bill, which one would you take?  So when faced with choices again… would you rather take a refrigerator someone spent $100 to make and try to sell it for more than $1,000 or would you rather someone give you $100 cash and you do whatever you want to try to turn that into more than a thousand bucks? On the one hand you have a refrigerator which might have a decent retail market and on the other hand you have cold hard cash that you can do anything with to try and make the necessary profit. You might choose refrigerator but you might choose the cash especially if you had a rock solid idea for that hundred bucks.

So when faced with choices again… would you rather take a refrigerator someone spent $100 to make and try to sell it for more than $1,000 or would you rather someone give you $100 cash and you do whatever you want to try to turn that into more than a thousand bucks? On the one hand you have a refrigerator which might have a decent retail market and on the other hand you have cold hard cash that you can do anything with to try and make the necessary profit. You might choose refrigerator but you might choose the cash especially if you had a rock solid idea for that hundred bucks. Credit has been screwy the last few years because government intervention is wreaking havoc on the market. The maximum allowable interest rate on an

Credit has been screwy the last few years because government intervention is wreaking havoc on the market. The maximum allowable interest rate on an