Business Lending

How LendingTree and SnapCap Crossed Paths

September 25, 2017 LendingTree in recent days revealed the acquisition of online platform for small business lending SnapCap’s non-lending assets in a $21 million deal, including $12 million upfront and $9 million in contingency payments. The deal gives online lending marketplace LendingTree more scale in the small business market ahead of what could shape up to be recovery in 2018.

LendingTree in recent days revealed the acquisition of online platform for small business lending SnapCap’s non-lending assets in a $21 million deal, including $12 million upfront and $9 million in contingency payments. The deal gives online lending marketplace LendingTree more scale in the small business market ahead of what could shape up to be recovery in 2018.

J.D. Moriarty, LendingTree Chief Financial Officer, told deBanked that SnapCap’s 20 employees will stay in Charleston, and the brand will remain intact. “For them, their employer just got both a whole lot more stable and scalable. As with anything we acquire, we will keep the brand in place and test it to see what is most effective,” said Moriarty.

LendingTree has been connecting small businesses with lenders since 2014, and the latest deal reflects a strategy to add scale.

“It’s a bit of what you might call an acqui-hire. LendingTree is growing quickly and scaling. We hired a really good team in SnapCap that will basically be our way of scaling in small business,” said Moriarty.

LendingTree is lifting its profile in the small business segment amid an industry transformation that is thinning the pack and has seen some players shifting gears entirely.

“Small business lending might do very well in 2018. And we are investing now to grow the base of our business. On a macro level, we expect our business to do well in 2018 regardless. But if small business lending recovers and suddenly you see companies like OnDeck doing well, we will benefit from that. But we position any acquisition assuming that the market doesn’t recover and the deal still must be attractive to us, even if the market continues to struggle.”

Moriarty went on to provide a glimpse into the financial structure of the deal.

“Last year, SnapCap set up a special purpose vehicle (SPV), which was funded by outside capital with which they would actually make loans. There’s a balance sheet aspect to that business we are not acquiring. But it was a small percentage of their business,” Moriarty explained.

Inside the Marketplace

LendingTree is largely known as a marketplace for mortgage loans where they represent about 50 percent of comparison shopping for mortgages. “That is how people think of us for sure,” said Moriarty. The revenue drivers have expanded in recent years, however.

For instance, mortgages used to account for 90 percent of revenue. Today, based on the most recent quarter, less than half of business originates from mortgages while the balance is in personal loans, credit cards, home equity, small business and auto loans.

LendingTree is no stranger to acquisitions, having done five such deals since June 2016. “What we’re trying to do is to build other marketplaces where people want to comparison shop,” said Moriarty.

But growth by acquisition is not their only growth strategy. “We’re growing period,” said Moriarty, adding that organic growth has been very good but small business in particular is a tough market to scale.

One of the recent deals, the acquisition of CompareCards a year ago, led them to gain market share in the credit card space. That deal also led LendingTree to SnapCap. CompareCards founder and president Chris Mettler and his wife own more than a one-third equity stake in SnapCap.

“SnapCap was introduced to us through Chris. He’s now a LendingTree employee. The introduction was absolutely from him. But it’s very consistent with our strategy, which we have conveyed to the market. We will continue to make small, accretive acquisitions and that will help us to gain scale in certain businesses and diversify,” said Moriarty.

Hybrid Model

While LendingTree and SnapCap both facilitate loans to the small business community, they take slightly different approaches to get there. “SnapCap’s core business is not unlike ours, meaning they are essentially finding high quality leads for lenders,” said Moriarty.

SnapCap uses a concierge model in which customers have a broker experience. They talk to someone at the company who helps them to identify a lender.

“LendingTree will be bigger and more scalable through both the traditional LendingTree model and SnapCap’s concierge approach. We will simply be able to serve lenders more effectively. If I’m a lender making small business loans, this is a pretty good thing.” he said.

SnapCap, meanwhile, is looking forward to the very same scale that LendingTree is targeting.

“The mission of SnapCap has always been to serve small business owners with access to funding. LendingTree’s leading online lending marketplace combined with SnapCap’s successful concierge model will enable us to serve an even wider range of business owners,” Hunter Stunzi, co-founder of SnapCap, told deBanked.

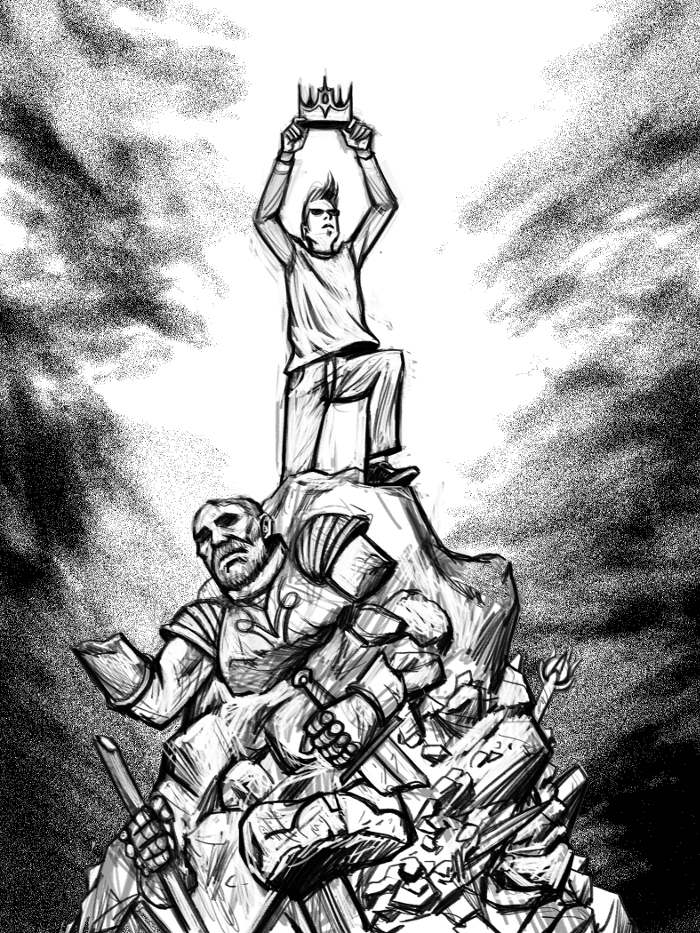

Bizfi Survives, Thanks to World Business Lenders Asset Purchase Deal

September 22, 2017 The Bizfi marketplace is slated to live on, according to Stephen Sheinbaum who joined World Business Lenders (WBL) as a managing director in July. On Wednesday, WBL purchased several assets from Bizfi including the brand, the marketplace, the Next Level Funding renewal book, and other related pieces of the company, he says. Sheinbaum founded Bizfi (then Merchant Cash and Capital) in 2005.

The Bizfi marketplace is slated to live on, according to Stephen Sheinbaum who joined World Business Lenders (WBL) as a managing director in July. On Wednesday, WBL purchased several assets from Bizfi including the brand, the marketplace, the Next Level Funding renewal book, and other related pieces of the company, he says. Sheinbaum founded Bizfi (then Merchant Cash and Capital) in 2005.

WBL, a Jersey City-headquartered small business lender will also be a lender on the platform.

Other key Bizfi personnel have joined WBL including former Managing Director of Renewals John BellaVia, VP of Sales Michael Caronna, and Sales Manager Ryan Bressler.

The asset purchase does not affect the deal forged with Credibly to service the $250 million portfolio, Sheinbaum explains, which is separate.

While lesser known among the mainstream fintech media, WBL has been a stalwart player in the non-bank lending industry for years. Their ambitions and size became more apparent when deBanked attended their invite-only annual shareholder meeting at the Waldorf Astoria in NYC in 2015. The company went on to open a massive office in Jersey City in July 2016 that was attended by Jersey City Deputy Mayor Marcos Vigil, Councilwoman Candice Osborne, Archbishop David Billings and Mitchell Rudin, the CEO of Mack-Cali. At the ceremonial ribbon cutting, WBL CEO Doug Naidus said that he wanted to build a company that lasts, one that he can look back on and be proud of.

Now with the Bizfi brand and marketplace in tow, the company is uniquely positioned.

“[It’s a] game changer here,” Sheinbaum said. “2.0 here we come!”

The Top Small Business Funders By Revenue

September 14, 2017Thanks to the Inc 5000 list on private companies and earnings statements from public companies, we’ve been able to compile rankings of alternative small business financing companies by revenue. Companies that haven’t published their figures are not ranked.

| SMB Funding Company | 2016 Revenue | 2015 Revenue | Notes |

| Square | $1,700,000,000 | $1,267,000,000 | Went public November 2015 |

| OnDeck | $291,300,000 | $254,700,000 | Went public December 2014 |

| Kabbage | $171,800,000 | $97,500,000 | Received $1.25B+ valuation in Aug 2017 |

| Swift Capital | $88,600,000 | $51,400,000 | Acquired by PayPal in Aug 2017 |

| National Funding | $75,700,000 | $59,100,000 | |

| Reliant Funding | $51,900,000 | $11,300,000 | Acquired by PE firm in 2014 |

| Fora Financial | $41,600,000 | $34,000,000 | Acquired by PE firm in October 2015 |

| Forward Financing | $28,300,000 | ||

| IOU Financial | $17,400,000 | $12,000,000 | Went public through reverse merger in 2011 |

| Gibraltar Business Capital | $16,000,000 | ||

| United Capital Source | $8,500,000 | ||

| SnapCap | $7,700,000 | ||

| Lighter Capital | $6,400,000 | $4,400,000 | |

| Fast Capital 360 | $6,300,000 | ||

| US Business Funding | $5,800,000 | ||

| Cashbloom | $5,400,000 | $4,800,000 | |

| Fund&Grow | $4,100,000 | ||

| Priority Funding Solutions | $2,600,000 | ||

| StreetShares | $647,119 | $239,593 |

Companies who were published in the 2016 Inc 5000 list but not the 2017 list:

| Company | 2015 Revenue | Notes |

| CAN Capital | $213,400,000 | Ceased funding operations in December 2016, resumed July 2017 |

| Bizfi | $79,000,000 | Wound down |

| Quick Bridge Funding | $48,900,000 | |

| Capify | $37,900,000 | Wound down |

Square Wants to Become a Bank

September 6, 2017 Square is expected to apply for an Industrial Loan Company (ILC) bank charter this week, according to American Banker and other sources. Like SoFi, who is busy trying to do the same thing, their attempt will also face competitive resistance.

Square is expected to apply for an Industrial Loan Company (ILC) bank charter this week, according to American Banker and other sources. Like SoFi, who is busy trying to do the same thing, their attempt will also face competitive resistance.

In June, Richard Hunt, president and CEO of the Consumer Bankers Association (CBA), told deBanked that in the case of SoFi, “The whole world is evolving, fintech is evolving. This was inevitable one way or another.” It is therefore not entirely surprising that Square is following SoFi. Others may wait to see how the regulatory debate plays out before putting in applications of their own, however.

“No one envisioned when they wrote the ILC charter that we would have fintech companies that finance mortgages and student loans from private equity capital and not deposits. It’s a new world. Like with all rules and regulations, federal regulators should periodically review longstanding policy,” Hunt said.

Several people from the banking industry argue that the ILC charter route is a loophole and that if fintech companies exploit it and screw up, they could put the entire banking system at risk.

Christopher Cole, executive vice president and senior regulatory counsel at the Independent Community Bankers of America (ICBA), previously said, “We have been fighting the ILC charter for over a decade. When Walmart tried to apply for an ILC charter in 2006 we objected at that point. And that resistance was part of the reason why they never got a charter.”

On August 25th, Congresswoman Maxine Waters requested that a hearing be held on ILC charters to weigh all the concerns before acting on new ILC applications.

Until then, just because Square wants to become a bank, doesn’t mean they will succeed in doing so.

No, Able is Not Going Out of Business, Company Says

September 5, 2017

An industry blog appears to have stretched the truth, again.

On September 1st, Lending Times published a story that relied on an anonymous source to suggest that Austin,TX-based Able Lending is going bankrupt and selling their portfolio. No other compelling evidence is offered other than Lending Times not having their messages returned. No clues as to what kind of knowledge the source might have and why they have it is provided.

Another blog piled on top of that story by circulating an email this afternoon with “Able Lending closing down?” in the subject line. That blog also wrote that their messages were not returned.

I personally reached out to Able and received an immediate response. Company CEO Will Davis pointed out a flaw with Lending Times’ anonymous source. “This anonymous source doesn’t seem to be anyone close to Able, because Able does not own a portfolio of loans (it originates and distributes loans to direct lenders, who then hold those loans on their balance sheet) and therefore has no portfolio to sell,” he said.

Davis also speculated that there could be an ulterior motive. “We believe this story originated by the fact that we’ve been in active discussions with a number of originators to acquire Able, and there’s a non-zero chance this story was placed in order to throw an interested party off the trail,” he explained.

“In any event, we have no plans to go out of business and no plans to declare bankruptcy,” he concluded.

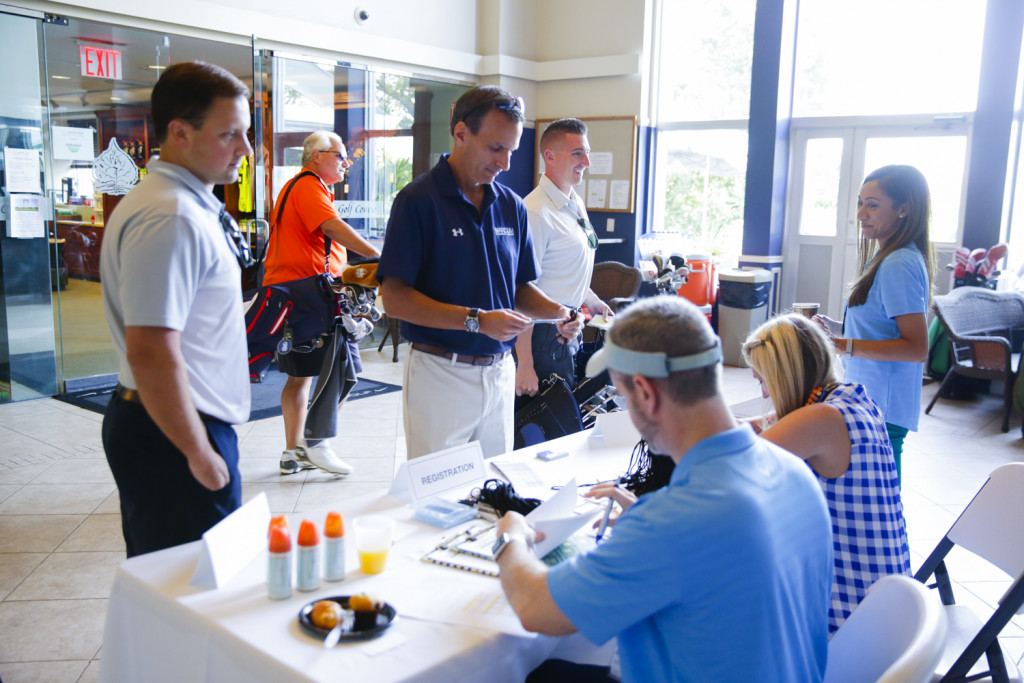

deBanked Golf Outing 2017 Photos

August 29, 2017Thanks to Marine Park Golf Course in Brooklyn, NY for having us! And thanks to all who came and sponsored!

Why BFS Capital’s Glazer Is Passing the Torch

August 22, 2017

Marc Glazer co-founded BFS Capital in the early 2000s and has remained at the helm all this time – until now. Glazer has passed the torch over to Michael Marrache, effective last week. He isn’t going too far, as the former chief executive will remain chairman of the board working alongside Marrache on the next chapter for the MCA and small business lending company. Meanwhile the executive pair points to a future not only where there is sustainability but where there is growth.

“We’ve obviously grown the company year after year over the last 15 years, and as with every other type of business and industry there were ebbs and flows. Over the last couple of years with a significant amount of challenges going on, we as a company decided we want to continue to grow but we want to grow in a way that benefits the company from a profitability standpoint as well as serves our customers,” said Glazer.

In April 2017, BFS Capital surpassed $1.5 billion in financings since inception. The company expects to fund more than $300 million in new financings in this calendar year.

“We’ll increase our reliance on algorithmic solutions, transparency in the ISO and customer experience and we will increase the number of financing solutions. Culture is significant for us and we will continue to build on the legacy Marc created,” said Marrache.

Marrache takes the reigns at a time when the industry is at a crossroads that will leave some alt lenders in the dust while other rise to the occasion.

“The stories that were challenging in 2016 look good in 2017,” said Marrache, pointing to OnDeck’s forthcoming profitability, Kabbage’s lofty valuation, CAN Capital’s return to funding, PayPal’s acquisition of Swift Financial and Prosper looking good.

“We think alternative and non-bank lending are in a good place. And yes, some of the folks that are no longer operating in this space were overextended or may have exhibited irrational behavior for pricing or customer acquisition costs. We think what we’re witnessing is the normal lifecycle of the industry. There were lots of participants earlier. Now to participate the industry must show a bit more control and sophistication. If you execute well, the tomorrows will be better than 2016,” said Marrache.

And according to Glazer, because of the changes in the business environment over the last couple of years, it’s going to require a different skillset to take BFS Capital to the next level.

“There are clear differences between starting a company, growing a company and becoming a billion-dollar small business financing platform. We’ve needed to evolve at each stage and now again with Michael’s leadership,” he said.

For Glazer, Marrache was almost always the succession plan.

“To be fair, hiring Michael four years ago, maybe succession planning was in the back of my mind somewhat. But as our relationship developed and as he was COO for three-plus years and then president, it became apparent that Michael’s skill set, passion, desire and how he looked at culture were all similar to myself. Let’s grow, but let’s watch our numbers. Make sure we treat people fairly. And for the businesses we are financing — provide thoughtful capital to help them versus creating problems for them,” said Glazer.

More Funding

BFS Capital’s business model is comprised both of MCAs and small business loans. Alternative funding company CAN Capital does both MCAs and loans and had to pause lending until recently. For BFS, however, it’s all systems go. And that means unequivocally continuing to fund small businesses.

“Absolutely, yes. And there’s no quizzicality in mind. I would say we are going to continue funding small businesses and fund more of them this year than we did last year. And we will fund even more the year after. So absolutely,” Marrache said.

BFS Capital sells through both ISOs and directly to merchants, the former of which is where most originations derive. “There are a number of solutions we are putting together to benefit that network,” said Marrache, adding he doesn’t believe algorithmic solutions will replace underwriters.

“We have a strong legacy of customer underwriting. We believe lower level transactions can be significantly more automated. Above a certain level and certain amounts of origination, we think algorithms and data solutions at that point are a facilitator, not a replacement of our underwriting,” Marrache said.

The Legacy

There was a time when BFS Capital’s growth plans included debuting in the public markets. Those plans have since been sidelined amid a chilly investor reception for alternative lender stocks.

“We spent a lot of effort in our filing,” said Glazer. “But at the end of the day, the market for the space had softened. Going forward I think it’s really going to be a question of what the markets look like and what makes sense for our company. We will evaluate that as the situation warrants.”

IPO or not, it appears Glazer’s legacy is still being written.

“I co-founded the company 15-plus years ago. Before finance and accounting, at heart, I’m an entrepreneur. That’s what I do, what I enjoy. I love starting companies, having the vision and creating things,” he said.

As chairman of the board and a major stakeholder, Glazer will continue to be active in BFS Capital.

Tech Banks: Will Fintech Dethrone Traditional Banking?

August 20, 2017On Halloween, 2014, a largely unknown, Boston-based financial institution, First Trade Union Bank, embraced high-technology, went paperless, and officially adopted a new name: Radius Bank.

In reinventing itself, Radius did more than dump its dowdy moniker. It shuttered five of its six branches, re-staffed its operations with a tech-savvy team, instituted “anytime/anywhere” banking services, and offered customers free access to cash via a nationwide ATM network. And it teamed up with a fistful of financial technology companies to offer an impressive array of online lending and investment products.

In reinventing itself, Radius did more than dump its dowdy moniker. It shuttered five of its six branches, re-staffed its operations with a tech-savvy team, instituted “anytime/anywhere” banking services, and offered customers free access to cash via a nationwide ATM network. And it teamed up with a fistful of financial technology companies to offer an impressive array of online lending and investment products.

Today, the bank’s management boasts that, using their personal mobile phones, some 2,700 people per week are opening up checking accounts, funneling $3 million in consumer deposits into the bank’s virtual vault. That’s a stark contrast from a decade ago when the financial institution was being rocked by the financial crisis and “we couldn’t get anybody to walk into our branches,” says Radius’s chief executive, Mike Butler.

“We tried to leave that old bank behind,” he says. “We’re a virtual retail bank now, an efficiently run organization that offers high levels of customer service and Amazon-like solutions.”

Radius Bank is not alone. At a moment when there is much discussion — and hand-wringing — over the future of seemingly outmoded, highly regulated community banks, a coterie of small but nimble banks is exploiting technology and punching above its weight. Almost overnight, this cohort is combining the skill and hard-won experience of veteran bankers with the lightning-fast, extraordinary power afforded by the Internet and technological advances. As a result, these small and modest-sized institutions are redefining how banking is done.

In addition to Radius Bank, independent banks winning recognition for their bold, innovative – and profitable — exploitation of technology, include: Live Oak Bank in Wilmington, N.C., which adroitly parlays technology to become the No. 2 lender to business and agricultural borrowers backed by the U.S. Small Business Administration; Darien Rowayton Bank in Darien, Conn., which is making a name for itself with coast-to-coast, online refinancing of student loans; and Cross River Bank in Fort Lee, N.J., which does back-end work for a passel of fintech marketplace lenders.

Interestingly, there’s not much overlap. Each of the banks goes its own way. But what all the banks have in common is that each has struck out on its own, each hitting upon a technological formula for success, each experiencing superior growth.

“These are companies that understand the value of a bank charter,” says Charles Wendel, president of Financial Institutions Consulting in Miami. “They have to work under the watchful eyes of state and federal regulators. But their cost of funds is low and they can offer more attractive rates. Because they’re less likely (than nonbank fintechs) to disappear, run out of money, or get sold,” the bank expert adds, “they also have the image of stability with customers.”

These modest-sized banks are emerging as not only pacesetters for the banking industry. Along with making common cause with the fintechs — which had promised to disrupt the banking industry – they’re even beating the fintechs at their own game.

“Classically, community banks have looked to technology partners to provide technological innovation,” says Cary Whaley, first vice-president for payment and technology policy at the Independent Community Bankers of America, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing a broad swath of the country’s 5,800 Main Street banks. “They still do. You’re seeing more partnerships. But now you also see community banks building innovative products and services outside of that relationship. You see forward-thinking banks developing their own technology to support big ideas like marketplace lending, distributed ledger technology, and emerging payments technology.”

With its extraordinary skill at exploiting technology, Live Oak Bank – which trades on the Nasdaq and is the only public company encountered in the cohort — has become a Wall Street darling. “While several banks have adopted an online-only model, and nearly all banks are shifting more and more delivery through online channels, Live Oak was built from the ground up as a technology-based bank,” Aaron Deer, a San Francisco-based research analyst at Sandler O’Neill Partners, wrote in a recent investment note.

Driving the success of Live Oak, which operates out of a single branch in the North Carolina seacoast town and has only been in business for a decade, is the explosive growth in its SBA lending, the bank’s “core strategy,” Deer notes. Last year, Live Oak lent out $709.5 million in SBA loans in increments of up to $5 million, the federal agency reports, making it the country’s No. 2 SBA lender. It trailed only megabank Wells Fargo Bank, the third largest bank in the U.S. with $1.5 trillion in assets, which made $838.93 million in SBA-backed loans last year.

As its SBA lending has taken off, Live Oak, which qualifies as a “preferred lender” with the federal agency, boasts assets that have nearly tripled to $1.4 billion in 2016, up from $567 million two years earlier. Those are flabbergastingly fantastic growth numbers. But just as incongruously — by nipping at the heels of Wells Fargo — Live Oak has been challenging a bank more than a thousand times its asset size for dominance in SBA lending.

And, interestingly, the bank is able to book those outsized amounts of SBA loans while lending to only 15 industries out of 1,100 approved by the government agency, slightly more than 1% of the universe. That’s up from 13 industries in 2015, and Live Oak is adding two to four additional industries yearly for its SBA loan portfolio, Deer reports. Included among the industries to which the bank made an average SBA loan of $1.29 million last year: Agriculture and poultry, family entertainment, funeral services, medical and dental, self-storage, veterinary, and wine and craft-beverage.

The bank has a team of financing specialists dedicated to each of the designated industries. Among Live Oak’s current SBA borrowers are Martin Self Storage in Summerville, S.C.; Utah Turkey Farms in Circleville, Utah; Pinballz Arcade, Austin, Tex.; and Council Brewery Company in San Diego. Steve Smits, chief credit officer at the bank, told NerdWallet: “When you specialize in something, you become efficient. Because we do it every day and we have professionals and specialists, we tend to be more responsive and quicker.”

The heady combination of technological sophistication and banking expertise has allowed the lender to slash its loan-origination time to 45 days, about half the three-month industry average for SBA loans. To speed up loan sourcing and generation, the bank developed its own in-house technology, which led to the formation of the Wilmington-based technology company nCino, which was spun off to shareholders in 2014.

Live Oak did not return calls to discuss its lending strategies, but in SEC filings bank management declared: “The technology-based platform that is pivotal to our success is dependent on the use of the nCino bank operating system” which relies on Force.com’s cloud-computing infrastructure platform, a product of Salesforce.com.

Natalia Moose, a public relations manager at nCino told deBanked in an e-mail interview: “We work with Live Oak Bank, in addition to more than 150 other financial institutions in multiple countries with assets ranging from $200 million to $2 trillion, including nine of the top 30 U.S. banks. nCino was started by bankers at Live Oak Bank who found the logistics of shuffling paperwork among loan stakeholders to be unwieldy, inefficient and time-consuming.

“nCino’s bank operating system,” Moose adds, “leverages the power and security of the Salesforce platform to deliver an end-to-end banking solution. The bank operating system empowers bank employees and leaders with true insight into the bank, combining CRM (customer relationship management), deposit account opening, loan origination, workflow, enterprise content management, digital engagement portal, and instant, real-time reporting on a single secure, cloud-based platform.”

Live Oak, meanwhile, is not resting on its technological laurels. According to Deer’s report, the bank’s parent company, Live Oak Bancshares, has formed a subsidiary to inject venture capital into fintech companies. It’s already taken a small equity stake in Payrails and Finxact, “the latter of which is developing a completely new core processor to compete against the old legacy systems used by most banks,” the Sandler O’Neill analyst writes. “Quite simply,” he asserts elsewhere in his report, “the company is far beyond any other bank we cover in its technical capabilities and the growth outlook remains outstanding.”

Five hundred and thirty-three miles due north along the Atlantic coast in southeastern Connecticut, Darien Rowayton Bank is also experiencing tremendous success as a lender using a home-grown technology platform. State-chartered by the Connecticut Department of Banking and regulated as well by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the $600 million-asset bank is winning attention in banking circles for its online student-loan refinancing.

Five hundred and thirty-three miles due north along the Atlantic coast in southeastern Connecticut, Darien Rowayton Bank is also experiencing tremendous success as a lender using a home-grown technology platform. State-chartered by the Connecticut Department of Banking and regulated as well by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the $600 million-asset bank is winning attention in banking circles for its online student-loan refinancing.

A few years ago, DRB, as it is known, was looking to go beyond mortgage and commercial lending — “the bread and butter for most community banks,” bank president Robert Kettenmann explained to deBanked in a telephone interview – and was somewhat at a loss. The bank considered but then rejected the credit card business. Finally, DRB struck paydirt refinancing student loans. “Our chairman really seized on the opportunity,” Kettenmann says, adding: “It’s a $35 billion market.”

Thanks to the National Bank Act, it’s able to operate in all 50 states. As a regulated commercial bank with a strong deposit base, DRB can also offer low rates well below any state’s usury prohibitions.

What is most striking about DRB’s program is its nationwide targeting of upwardly mobile, affluent young professionals. According to a PowerPoint presentation obtained by deBanked, all of the bank’s super-prime borrowers, who are mainly in the 28-34 age bracket, have a college degree and a whopping 93% have graduate degrees. Average income is $194,000.

Forty-eight percent of those refinancing student loans with DRB are doctors or dentists and another 22 percent are pharmacists, nurses or medical employees; only about 20% are paying off their law degrees or MBAs. The heavy concentration of refinancing in the medical field reduces economic risk in an economic downturn. Forty-three percent of the borrowers are home-owners, the rest are renters – and prime candidates for an online, DRB-financed mortgage.

Forty-eight percent of those refinancing student loans with DRB are doctors or dentists and another 22 percent are pharmacists, nurses or medical employees; only about 20% are paying off their law degrees or MBAs. The heavy concentration of refinancing in the medical field reduces economic risk in an economic downturn. Forty-three percent of the borrowers are home-owners, the rest are renters – and prime candidates for an online, DRB-financed mortgage.

(Once known as “yuppies” today this cohort is “known by the acronym ‘HENRY,’” remarks Cornelius Hurley, a Boston University banking professor and executive director of the Online Lending Institute, explaining the initials stand for “High Earners Not Rich Yet.”)

The Connecticut bank partnered with a third-party on-line vendor, Campus Door, when it commenced making student loans in 2013. In the fall of 2016, however, DRB built out its own, proprietary loan-origination system, Kettenmann reports, emphasizing that CampusDoor had been an excellent partner but that the bank wanted to exercise end-to-end control over the process. DRB employs a seven-pronged, “omni-channel” marketing approach that includes interactive marketing, affinity partnerships, digital/online advertising, direct mail, mass-media advertising, and public relations/brand awareness campaigns.

DRB’s online enrollment provides “pre-approved rates” in less than two minutes with final approval on rates in 24-48 hours. Refinancers can complete the online application at their own speed. Through May, 2017, DRB had made $2.48 billion in refinancing to 20,000 student-loan borrowers, with only ten defaults, five of which were attributed to deaths or “terminal illness.”

On Yelp! the bank has received a batch of reviews ranging from very favorable, five-star (“I had a truly wonderful experience”) to one-star (“awful” and “truly a nightmare”). Many fault the application process as laborious, describing it as “time-consuming.” But for those who have succeeded, like the reviewer who counseled “patience,” the result can be “the lowest rate with DRB…my loan payments went down $100 a month.”

Just about an hour’s drive south and taking its name from its proximity to New York city just over the George Washington Bridge is New Jersey-based, state-chartered Cross River Bank, which has a reputation as a partner-in-arms to fintech companies. “We’re both users and producers of technology,” declares Gilles Gade, the bank’s chief executive.

Just about an hour’s drive south and taking its name from its proximity to New York city just over the George Washington Bridge is New Jersey-based, state-chartered Cross River Bank, which has a reputation as a partner-in-arms to fintech companies. “We’re both users and producers of technology,” declares Gilles Gade, the bank’s chief executive.

The bank provides “back-end” and infrastructure support to 17 marketplace lenders that offer a suite of lending products including personal loans, mortgages and home-equity loans. Following loan origination by a fintech company – Marlette Funding, Affirm, Upstart, loanDepot, SoFi, and Quicken Loan, among other partners — Cross River does the actual underwriting. Last year, Gade reports, the bank underwrote 1.9 million loans valued at $4-4.5 billion, about 10% of which Cross River kept on its books. The bulk of the loans are sold “back to the marketplace lenders” or to a third party. “We’ve created a high-velocity automated system,” he says.

Gade is manifestly unapologetic about the bank’s role in assisting fintechs in their competition with the banking establishment. “We’re a banking infrastructure services provider for those who want to disrupt the banking system,” he says. “Consumers expect a lot better than they’ve been getting from traditional banking services.”

Back in Boston, Radius Bank’s chief executive reports that forging partnerships with fintechs to provide the full panoply of online banking services was no easy proposition. In its mating ritual, Radius not only had to determine that a fintech company’s offerings were sound and that it had the right characteristics – most especially “a long-term, sustainable business model” – but that its corporate culture meshed comfortably with Radius’s.

Back in Boston, Radius Bank’s chief executive reports that forging partnerships with fintechs to provide the full panoply of online banking services was no easy proposition. In its mating ritual, Radius not only had to determine that a fintech company’s offerings were sound and that it had the right characteristics – most especially “a long-term, sustainable business model” – but that its corporate culture meshed comfortably with Radius’s.

After meeting with as many as 500 fintechs and after a fair amount of trial and error, Radius formed partnerships with LevelUp, which enables customers to make mobile payments; with online lender Prosper, for refinancing consumer debt and “credit rehabilitation”; with SmarterBucks, for refinancing student loans; and with online investment firm Aspiration Partners – which allows investors to name their own fees and markets itself to a predominately middle-class audience as the firm “with a conscience.”

Radius employs advertising on social media websites and employs “psychographics” to appeal to “anyone who is zealous about using technology, not necessarily millennials,” Butler says. The data show that 65% of adults in the U.S. would prefer to use a traditional bank and have face-to-face interactions with a teller, he notes, leaving the remaining 35% as Radius’s target audience.

Christopher Tremont, executive vice-president for virtual banking, told deBanked that a typical Radius customer is 42 years old, lives in Boston, New York, Chicago “or one of the bigger cities in the West,” is a “technophile,” earns $75,000 a year, and has $100,000 in personal assets.

Radius’s performance since it went paperless has been stellar. The bank has seen a rapid rise in deposits, spurting to $782 million through the first quarter of 2017, up from $565 million at year-end 2014. With little fee income but ample deposits and low-cost funds, Radius realizes the bulk of its revenues – and profits — on the interest-rate spread generated from its loan portfolio.

The bank booked $43.5 million in SBA loans last year, ranking it in the top 50 banks on the SBA’s league tables, while carrying another $105 million in its commercial leasing business at the end of the first quarter this year. Loan generation is driving asset growth, which are currently at $973 billion, up more a third from $726 million in 2014, and Butler expects the bank’s assets to top $1 billion sometime this year.

“Community banks love that part of the business—lending money,” Butler says.