p2p lending

Is Alternative Lending An Illusion? (LendIt 2015 Summary)

April 18, 2015More than 2,400 people packed into the LendIt conference last week in New York City and everywhere you turned, startups were boasting of their ability to lend billions of dollars to underserved consumers and businesses. Companies not even old enough to have attended last year’s LendIt conference had reportedly lent tens of millions or hundreds of millions of dollars already. Is it all an illusion?

Investors circled like hawks to try and grab an opportunity into this exploding market. Alternative lenders were practically being tackled by VCs, Private Equity firms, and specialty finance lenders:

Technological innovation is disrupting the status quo, attendees echoed. Surely banks can afford to develop new technology to compete, so why haven’t they? Lendio’s Brock Blake wasn’t afraid to challenge the Short Term Business Lending Panel on this. “Is there real innovation happening or is there regulatory arbitrage?” he asked.

The panelists mostly agreed that it was a combination of both. Stephen Sheinbaum, founder of Merchant Cash and Capital (MCC) and BizFi, said “regulation is not something that scares us in any way.” That’s not surprising considering MCC has survived more than ten years in business and fellow panelist CAN Capital has survived more than seventeen.

But for the newer players entirely reliant on third party brokers or dependent on a Reg D exemption to issue securities, their success may indeed be regulatory arbitrage. And time is on their side.

Karen Mills, the former head of the Small Business Administration asked several regulatory bodies who would stand up to oversee small business lending. “No one stood up,” she said.

It’s the brokers that worry some folks most, an issue that PayPal and Square Capital do not have to contend with at all. OnDeck CEO Noah Breslow stated, “there is always going to be a set of customers that want to shop and want to have help.”

Kabbage’s Kathryn Petralia explained that only 2% of their business comes from brokers and their fees are capped at 4%. CAN Capital’s Jason Rockman argued that it’s about working with brokers that share their values. MCC’s Sheinbaum said, “you have to be willing to not do business with some of the unscrupulous players out there.”

But while these industry captains minimized the role that brokers play, 2015 is already being dubbed the Year of the Broker.

The regulatory environment isn’t the only issue to be worried about, skeptics argued. There was cautious alarm about the market’s viability when interest rates rise or the economy takes a turn for the worse.

“I think there’s going to be a shakeout,” said Steve Allocca of PayPal. MCC’s Sheinbaum explained that when he sees other funders doing deals that don’t appear to make sense, to not feel pressured to do them as well. “Stick to your disciplines. Stick to your guns,” he preached.

Fundation CEO Sam Graziano argued that small business lending is already very risky. The lifetime default rate on 7(a) SBA Loans is 20%, he said. Graziano, who hates the term alternative lending prefers to refer to the industry as digitally enabled lending.

And digitally enabling is something that OnDeck has focused on. In Breslow’s presentation, he said that applying offline for a loan takes 33 hours of work on average. Banks are shuttering branches at a record rate, he added.

Banks are dead, said many in attendance. Kathryn Petralia of Kabbage disagreed. “The death of banks has been greatly exaggerated,” she argued on a panel.

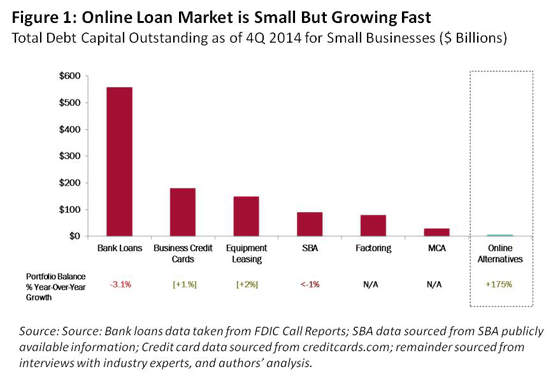

Indeed, Mills’ report shows that total outstanding debt on business loans by banks dwarfs the alternatives by more than 50 to 1.

But former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers is convinced the tide is turning.”The conventional financial sector has, in important respects, let all of its main constituents down over the last generation, and technology-based businesses have the opportunity to transform finance over the next generation,” he said during the keynote speech.

With conference sessions looking and feeling like a cramped NYC subway during rush hour, the popularity of alternative lending is no illusion.

But healthy skepticism is at least creeping in while the industry marches forward. Changes in regulations, interest rates, and economic activity will separate those simply riding a wave from those that have created something real. Expect companies that exhibited at this year’s conference to be gone by 2016 or 2017, said several panelists.

The final count of LendIt attendees was 2,493 people. 150 people who tried to register at the last minute were turned away. More are expected to attend next year.

Objectively, alternative lending appears to be very real.

A Q&A With LendingRobot

April 12, 2015 SEAN MURRAY (SM): I’m a casual Lending Club investor that has purchased more than 2,000 notes. I like to think that I’ve been pretty good with my picks but I feel like the rush to get the most attractive notes has only gotten more competitive. I’ve also got a perennial issue of idle cash and the pressure to put it to work on the platform can feel like a burden when I’m busy with everyday life. I feel like I can do better but I have reservations about relinquishing control.

SEAN MURRAY (SM): I’m a casual Lending Club investor that has purchased more than 2,000 notes. I like to think that I’ve been pretty good with my picks but I feel like the rush to get the most attractive notes has only gotten more competitive. I’ve also got a perennial issue of idle cash and the pressure to put it to work on the platform can feel like a burden when I’m busy with everyday life. I feel like I can do better but I have reservations about relinquishing control.

I noticed in January that you raised $3 million from Runa Capital, which caught my attention.

So for both myself and our readers, can you explain in a nutshell what LendingRobot does?

EMMANUEL MAROT (EM): First off, that ‘burden’ is the exact reason why we started LendingRobot, as my partner and I were feeling it as well! We automate the whole investing process (decision and execution) to simplify access to marketplace lending for individual investors.

EMMANUEL MAROT (EM): First off, that ‘burden’ is the exact reason why we started LendingRobot, as my partner and I were feeling it as well! We automate the whole investing process (decision and execution) to simplify access to marketplace lending for individual investors.

(SM): I think one of the biggest concerns for casual investors is the question of who physically possesses the cash. Obviously they have already come to accept that Prosper or Lending Club will hold their cash, but what about a service like yours? Do investors send you the money to invest it on those platforms?

(EM): That’s a very valid point. As of today, we do not have what the regulator calls ‘custody’ of the money. Our clients wire the money on the platform, they give us a programmatic access to their account there so we manage it for them. There is no way we can touch their money, and when the money is wired outside of the platform, it has to go back to the original bank account anyhow.

(SM): How do you bill for your fees? Do you need to provide bank account information? Credit card?

(EM): Since we cannot touch our client’s money, we need another way to charge our fees. We use credit card. Up to $10,000 we do not charge anything and clients don’t even have to enter a credit card.

(SM): What is the difference between your service and Lending Club’s Automated Investing?

(EM): As the issuer of the notes, Lending Club cannot offer an ‘unfair’ advantage to some investors, therefore their automated investing cannot be used to get access to the most popular assets. Obviously, it’s also entirely based on their own credit model, and one cannot benefit from a second layer of risk modeling. At last, we tend to offer more features, such as additional filtering criteria, cascading investment rules or cash-flow forecast. We posted a comparative explanation a while ago that is still somewhat valid: http://blog.lendingrobot.com/post/69219879518/lendingclub-re-introduces-prime

(SM): If I use your service, can I cancel it at any time?

(EM): Absolutely, no setup or entry fees, no exit fees, no minimum usage period.

(SM): There seems to be correlation between a borrower’s home state and the default rate, can I filter out certain states with your service?

(EM): Yes, not only do we offer over 25 different filtering criteria, but it’s possible to mix them freely. Some clients start with our own proprietary model, then add extra criteria, such as ‘36-months’, or ‘Exclude Nevada’.

(SM): What did you guys do before founding LendingRobot?

(EM): Tons of stuff! My partner and I met at Microsoft, which we both joined after selling our respective startups. We decided to create something together even before knowing what to do. Incidentally, we started the company with a very different project (see http://www.eventiles.com/). As mentioned above, we started LendingRobot out of personal need.

(SM): What’s the smallest amount someone can allow LendingRobot to manage if they just wanted to try it out?

(EM): Right now, our smallest client has… $66.49 invested! That being said, we recommend people to invest at least $5,000 to be diversified enough.

Background on Emmanuel Marot

Emmanuel Marot is a polymath and serial entrepreneur. A French ‘grandes école’ graduate with a major in Computational Finance, Emmanuel started his career in product marketing at Apple. He also worked for the French intelligence agency to modernize the handling and presentation of highly classified information and acted as freelance graphic designer.

At age 26, he created his first company, a Web agency that he grew up to 15 people while keeping the net operating margin above 30%. The company created the first virtual reality cd-rom (Guinness book of records, 1995) and produced mobile Internet services as early as 1996. After selling it, he co-founded a larger communication agency, with 400 employees and an annual turnover of 30 million Euro. In 2000, Emmanuel patented a novel way to access mobile sites and created his 3rd company, which Microsoft acquired six years later. Emmanuel orchestrated the move of the entire operations to Redmond, WA, and became Director, Mobile Search at Microsoft.

He left in 2008 to research algorithmic trading, predicting market reversals from search engine queries. In parallel, Emmanuel did multiple executive consulting engagements for startups and corporations. He began to focus his work on the design of algorithms to automate decisions, and co-created Eventiles, an iPhone application that crafts meaningful stories from bulk pictures.

In 2013, he combined his interests in finance and algorithms and co-created LendingRobot, a solution for marketplace lenders to automate and optimize their investments. Emmanuel passed the Series 65 Investment Adviser law exam in January 2014.

Lending Club Failure Has Shocking Twist

April 7, 2015 One general rule about meeting with a banker to apply for a loan is to not present yourself like a slob. That means dress professionally, comb your hair, trim your nails, sit up straight, be polite and sound as sophisticated as you possibly can. Then maybe, just maybe you might be seriously considered for an approval.

One general rule about meeting with a banker to apply for a loan is to not present yourself like a slob. That means dress professionally, comb your hair, trim your nails, sit up straight, be polite and sound as sophisticated as you possibly can. Then maybe, just maybe you might be seriously considered for an approval.

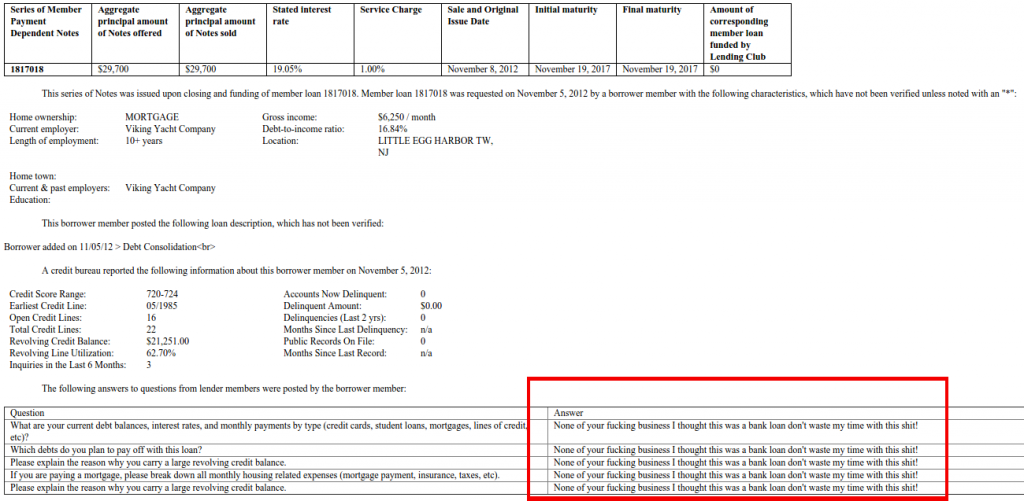

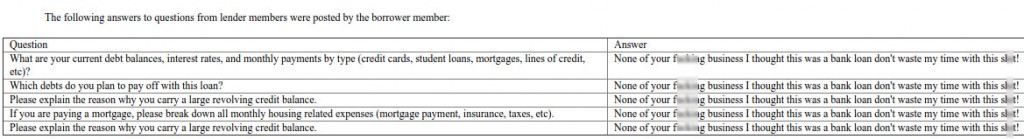

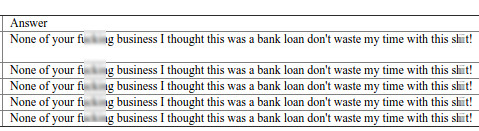

Well, things work a little bit differently out on the Internet. One applicant decided to try the opposite approach with Lending Club and their words became public record when the offering got registered with the SEC. Take a look:

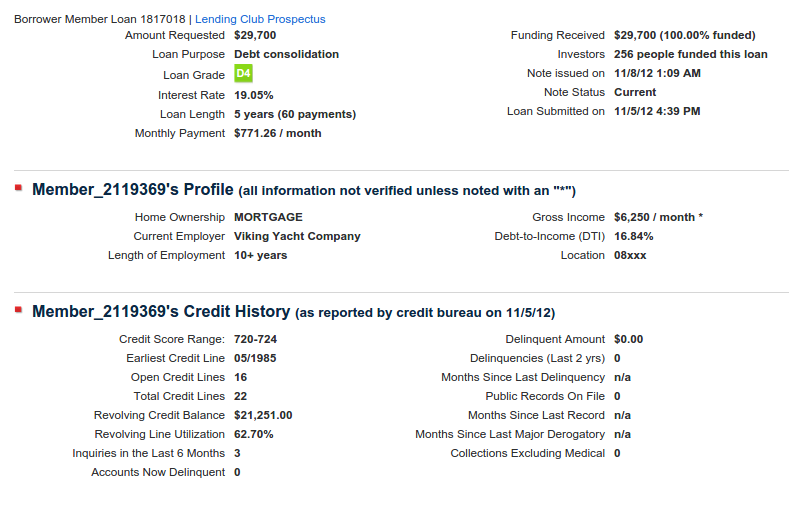

Just another D-grade note offering a 19.05% return. Oh wait…

Look closer at the applicant’s answers…

Congratulations, you just fast tracked yourself to the rejection bin! Oh wait, what’s that? You can check the loan number on the filing with the public data on Lending Club?…

Umm…

Behold the power of online lending!

F you, F that, Don’t waste my time with this sh*t and send me the damn $29,000.

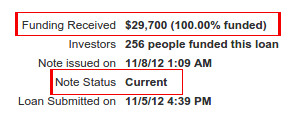

Sounds good to me! It was 100% funded and the borrower is currently in good standing. They are already halfway through their 5-year loan.

I honestly don’t know what to make of this. What’s crazier? The fact that 256 investors contributed money to it or the fact that the borrower is in good standing halfway into the 5-year loan?

You can find the original registered security here. Just search for the f bomb.

Yes, Rising Rates Will Impact Alternative Lenders

April 6, 2015 On April 1st, Ari Levy of CNBC posed the question, “what do rising rates mean for online lenders?”

On April 1st, Ari Levy of CNBC posed the question, “what do rising rates mean for online lenders?”

Right now, everyone’s lending so much that it’s hard to keep up with. There’s a waiting list for institutional investors to deploy capital into these platforms and even retail investors have been drawn away from stocks to earn 5% – 12% a year on risky three to five year notes.

To be frank, borrowers aren’t necessarily choosing alternative lenders over banks because of the rates. The ease of getting a loan online is part of the attraction. But even if the lending platforms raise their rates and the borrowers stick around, will the investors?

Peter Renton, founder of Lend Academy told Levy, “Nothing below 2 percent [federal funds rate] is much of a concern.”

According to the WSJ, Fed officials have estimated the federal funds rate to be 3.125% in 2017. That’s above Renton’s 2% threshold. This rise will inevitably translate into higher national savings account rates, which currently yield below 1% on average. There are definitely price points that will flush out retail investors from investing in platform notes.

Remember that around 2006, banks like HSBC were paying 5.5% APY. If such a scenario were to happen again, even if five years from now, how likely is it that a retail investor would place capital in an exotic, risky, and relatively illiquid 3-5 year note? I think the average retail investor would be willing to sacrifice a few percentage points and go for the absolute safety of an FDIC-insured account. I know I would.

It’s already possible to earn over 2% in a 5-year FDIC-insured CD. It’s not enticing yet but it’s getting warmer.

Given the choice between a 5% 5-year FDIC-insured CD and an 8-10% 5-year note backed by the full faith and credit of some dude on the Internet that needed a loan to pay for his medical expenses, I’m probably going with the CD. But with a savings account right now earning less than 1% and CDs barely earning more than that, right now my moneys riding on some dude.

– Myself

The allure of a Lending Club, Prosper, or note of any other marketplace lender is especially attractive right now because a savings account is where money goes to die. There’s stocks of course but there will always be stocks. They’re actually a good way to complement a portfolio in marketplace loan notes for diversity. A safe investment at present basically earns nothing so the average joe has an incentive to play around with alternative lending.

Just two months ago, Jorge Newberry, the Founder & Chief Executive Officer of American Homeowner Preservation LLC, declared peer-to-peer lending dead in his Huffington Post blog. His basis was that it’s all institutional investors doing the lending to peers now, instead of their actual peers. Give the remaining peers on the platforms a safer more liquid investment with an acceptable yield and the notion of peer-to-peer lending could be deader than dead.

First, disco bit the dust. Then, punk rock keeled over. Now, peer-to-peer lending has been annihilated. Who murdered P2P? Wall Street. BlackRock. Wealthy bankers. The guys I was shoulder-to-shoulder with last week in Las Vegas. At ABS Vegas 2015, billed as the largest capital markets conference in the world, the P2P/Online Lending 101 session attracted a Standing Room Only crowd.

However, this crowd was not made up of peers. These were killers.

-Jorge Newberry

As for short term business lenders and merchant cash advance companies, the turn time of an investment might only be six to twelve months. You’re not locked in for five years and the yields are typically better than consumer lending notes. There’s plenty of incentives for a retail investor who is syndicating to stick around even if rates rise.

And that brings me to the institutions lending to alternative lenders. I don’t know how much institutional investors expect to earn on consumer notes, but I have heard in the merchant cash advance industry that borrowing costs for the funders themselves can range from 8% to 18% APR. They might borrow money from a hedge fund for example.

That partially explains why costs to merchants are high, but it’s uncertain as to whether or not the institutions will just be able to raise their rates and pass along the increase or if there will be new yield opportunities elsewhere with less risk more fitting to their fancy.

My belief is that rising rates will indeed impact alternative lenders and retail investors will probably find safer places for their money pretty early on. As to what the institutional investors will tolerate and who can weather passed on cost increases without being hurt is yet to be seen.

Lending Club (LC) Q4 Earnings Call

February 23, 2015 The first company to bring platform lending into the public eye will release their 4th Quarter and 2014 earnings on Tuesday, February 24th at 5pm EST. Anyone can join the live webcast by clicking here. If not by a computer, you can also dial in by phone at 888-317-6003. Use conference ID 4117710 ten minutes prior to the start of the call.

The first company to bring platform lending into the public eye will release their 4th Quarter and 2014 earnings on Tuesday, February 24th at 5pm EST. Anyone can join the live webcast by clicking here. If not by a computer, you can also dial in by phone at 888-317-6003. Use conference ID 4117710 ten minutes prior to the start of the call.

Investor attitudes are likely to be affected by the outcome of OnDeck’s earnings. While the two companies have different models, they have generally followed the same ups and downs. Many investors are still not clear how they’re different. Lending Club earns fee income by servicing loans and is not exposed to the risk of the loans themselves. Some critics believe that puts them at odds with their platform lenders over the long term.

Lending Club has already experienced a low of $18.30 a share and a high of $29.29. It closed yesterday at $22.89.

Since going public a few months ago, they announced a partnership with Alibaba and Google.

The Industry’s Bad Paper

February 8, 2015 Sometimes deals go bad. But what happens next?

Sometimes deals go bad. But what happens next?

I just finished reading, Bad Paper: Chasing Debt From Wall Street to the Underworld on a recommendation from a friend. In it, author Jake Halpern walks readers through the shadowy world of consumer debt collection. It was eye-opening to say the least.

Halpern’s research uncovered that consumer debts with seemingly no original paperwork is sold, resold, and resold again to companies that the debtor never heard of and would not recognize. A debt’s record amounted to some fields on a spreadsheet where the information is not always correct and might even have been collected already by someone else.

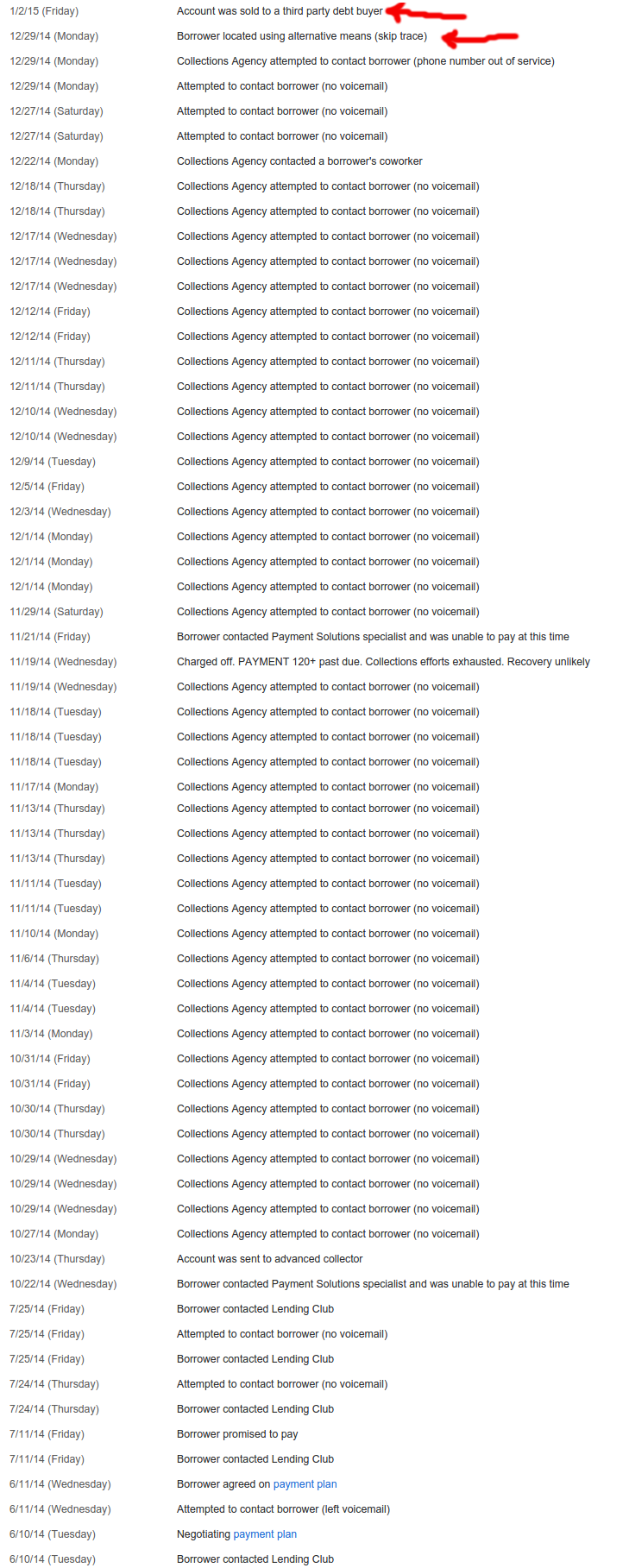

One has to wonder whose hands a Lending Club loan I participated in are in now. It was a $25,000 loan to a nurse. The notes below are from the real collections log provided by Lending Club. After making just 3 full payments on their 3-year loan, this 700 credit borrower went from negotiating a payment plan to off the grid. They called a co-worker, skip traced them, and finally gave up and sold her debt to a third party.

One has to wonder whose hands a Lending Club loan I participated in are in now. It was a $25,000 loan to a nurse. The notes below are from the real collections log provided by Lending Club. After making just 3 full payments on their 3-year loan, this 700 credit borrower went from negotiating a payment plan to off the grid. They called a co-worker, skip traced them, and finally gave up and sold her debt to a third party.

I’ve found that a lot of my defaulted loans thus far have gone bad in the first few months, a pattern that looked more like fraud than borrower hardship. It actually prompted me to call Lending Club and speak to a representative about it, who explained that they’re doing all they can to prevent fraud.

They were pretty relentless on this particular file, a nurse that was making $60,000 a year sounded like a winner. They had virtually no debt but the loan was supposedly used to consolidate outstanding debt into one monthly payment at the rate of 9.67%. The story didn’t exactly add up but since I don’t actually get to talk to the borrowers or look at their paperwork, I’m essentially just playing a numbers game.

That debt has been sold off and I as a note holder do not appear to be entitled to any money on the sale of it, not even pennies on the dollar. Bummer.

Because of platforms like Lending Club, I wasn’t the only one to lose out. 277 other retail investors who I don’t know and have never met participated in it with me. We’re all playing the numbers and we lost on this one.

With 1907 notes acquired on the platform so far, I’m not emotionally invested in any of them. How can I be? I have no idea who the borrowers are. I don’t even know their names! All I can do is diversify and make decisions based off of statistical analysis. If the borrower stops paying, go after them hard whoever they are!

Meanwhile in commercial transaction land

When it comes to merchant cash advance and business lending, the collection rules are different but so are the relationships. Even with strong advancements in automation, phone interviews remain an integral part of the underwriting process. A risk analyst typically calls the business owner, their landlord, and even several of their suppliers. Large dollar amount deals may even be presented to an entire risk committee for approval.

Suffice to say, pesky things like signed contracts do not usually prove elusive when a collector in this world gets their hands on it. Many commercial funding providers even record phone calls with the business owners where they get an additional verbal confirmation to the terms and conditions of the arrangement.

The collections process usually begins with the sales person or sales office that negotiated the terms with the business. Back when was I was an account rep, my commissions were paid in two pieces, upfront and a residual. That meant almost half my pay on a deal was tied to its performance. If a deal started to fall apart or defaulted, I had a personal stake in restoring the business to good standing.

The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act does not cover commercial transactions. And in the case of traditional merchant cash advances, there is likely no debt at all in a default, but rather a possible case of stolen receivables.

In the event where a deal I brokered was suspected of diverting receivables, I’d be the first one to know about it and the first person tasked with fixing it. That meant calls to the business, their home phones, their cell phones, and when necessary their landlord. If none worked, then their suppliers. The first goal was to determine if the business was still operating and in the vast majority of cases where defaults happened, they were.

Hardship was sometimes cited as a reason for breaching the agreement but not always. With a chunk of my paycheck on the line, I had to talk them back into good standing and unlike debt collectors, I didn’t have the ability to renegotiate the terms, lower a payment or cut them slack. It was back to the way it was or nothing.

It escalates

Some returned to good standing and others played hardball. The deal’s original underwriter might then involve themselves and if they failed, then on it went to the internal funder’s portfolio management/collections team.

This is why the situation here on out is different: Imagine a doctor sells you the accounts receivable of all his patients for a discounted price. The doctor gets cash upfront and the buyer will hopefully collect the full value of the accounts receivable to earn a profit.

Now imagine the doctor accepts your cash upfront and then also collects the accounts receivable from the patients and shuts you out. In traditional merchant cash advances, collectors aren’t going after debt, but rather acquired property that is rightfully theirs. The business has shut them out of receivables they purchased.

If internal collection efforts fail, they can attempt to freeze various receivables the business might have. Merchant processing proceeds are usually the first stop. If the business accepts credit cards, the merchant processor can be instructed to freeze all or a percentage of the revenues without a court order. This is easier said than done but it does work and there are even a few third party collection firms that specialize in this.

And if that doesn’t work? Well, thousands of lawsuits have been filed against businesses for breaching these commercial transactions. The business owners themselves can potentially be culpable and liable depending on the agreement and the nature of the breach.

And if that doesn’t work? Well, thousands of lawsuits have been filed against businesses for breaching these commercial transactions. The business owners themselves can potentially be culpable and liable depending on the agreement and the nature of the breach.

Some business owners are shocked to learn that a deal they made over the phone with people they never met will actually track them down and sue them. Unlike consumer debts which might only be a few hundred dollars, commercial transactions are typically tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of dollars. They will definitely pursue it.

On the largest default I ever presided over as an underwriter, the business owner said something to the effect of, “I stole your money. Let’s see how good you are at getting it back.” He said this just 24 hours after we had wired him the money. Ouch!

That happened more than six years ago but it was something I’ll never forget. A quick Google search today reveals that guy is still alive and kicking as he was recently interviewed about his success in amassing a restaurant empire in Florida.

Over the next couple years, I would hear variations of that “I stole your money” line from other businesses, typically on deals larger than $75,000. These were strategic defaults designed to strong-arm the funding company into a settlement or an attempt to simply walk off with the funds altogether. In other words, fraud.

All this does is raise the cost for the next business that conducts themselves honestly. It’s a damn shame.

Merchants prey on Wall Street

Critics can say what they want about the sophistication of businesses that enter into merchant cash advance transactions. Running a business requires a great deal of intelligence. And to some savvy businessmen, Wall Street’s money is on the menu as fresh meat.

Critics can say what they want about the sophistication of businesses that enter into merchant cash advance transactions. Running a business requires a great deal of intelligence. And to some savvy businessmen, Wall Street’s money is on the menu as fresh meat.

One experience I had was with the owner of a steakhouse in NYC that flew up from his residence in Brazil to try and close me (as the underwriter) on purchasing roughly $400,000 of his future credit card sales. What he didn’t know is that the night before I checked out the place anonymously by having dinner there with my wife. When the bill came, the server told me they no longer accepted credit cards. The next morning, the owner who spoke only in Portuguese arrived in tow with a translator and a lawyer. They traveled directly from JFK to our office, to which I informed them of the decline. They had stopped accepting credit cards a day too early for their scam on us to work and the restaurant closed two months later.

In another case, a souvenir shop in NYC asked if I would come by to pick up his application and statements in person since we were locally-based. After spending a half hour with the guy at his shop, I returned back to the office only to find out that he gave me doctored bank statements.

And then there’s the owner of a florist that made a career off of robbing merchant cash advance companies. The store, which is close to my hometown, had obtained more than 20 merchant cash advances by late 2008 and defaulted on all of them, netting the business close to $1 million. They hoped to make me victim number 21 but we figured it out in the 11th hour before the funds went out. The business is still there today though I’m unsure if it’s still the same owner.

In 2015, fake documentation is an epidemic. Underwriters in the industry cannot rely on faxed or emailed statements alone. They should be verified through APIs or through direct contact with banks. Many funding providers go a step further and actually request the usernames and passwords to business bank accounts just to be absolutely sure that what they’re seeing is what they’re getting.

But as tech-savvy millenials become the face of American small business, the ante is being upped on fraud. One underwriter told me they saw something even more worrisome, a fake bank website.

The scam is this: Knowing the underwriter is going to request the username and password of the business bank account to verify the statements, the applicant has designed a functional replica of a bank website on a web domain they own, one that looks like the bank name. The unsuspecting underwriter logs in to it and verifies the account data. There’s only one problem, it’s all fake.

While this appears to be an isolated event, it just goes to show that the war on bad paper is entering another phase.

Bad paper

While fraud is a substantial cause of the bad paper in the merchant cash advance and business lending industries, hardship does have its place. It is perhaps fortunate that in the commercial space, the paper isn’t sold off into some convoluted world of debt collection. More than likely the business will be dealing with the actual funding provider the entire way through the collections process, not a debt buyer ten levels down the chain. That’s good and bad for them.

It’s good because the owner will able to discuss matters related to the default with the party directly familiar with the original contract.

It’s bad because any chance that the contract and proof of the agreement will somehow get lost in the shuffle is pretty much nil.

Jake Halpern discovered that debtors can win lawsuits by simply challenging the debt buyer to produce evidence the debt is owed. That might work in the consumer world where debt changes hands ten times. On the commercial side, bad paper is an enduring companion. It may be business-to-business but somehow it’s more personal.

Contrast that with the Lending Club nurse who I know only as Member XXXXXXX. His/her debt is in the wind. I have no idea who they are, nor anything about the 277 other people that invested with me.

Halpern spent 256 pages tracing the path of a debt, the companies that bought it, sold it, stole it, and sued for it. It’s amazing how complex it is.

If he were to do a book on bad paper in merchant cash advance, it would go like this:

The business defaulted, the funding provider tried to collect and then sued. The End.

What’s up (or down) with OnDeck? [ONDK]

January 29, 2015 OnDeck took the market by storm back on December 17th, achieving a high share price of nearly $29. If 2014 was the breakout year for alternative lending, then early 2015 is feeling a bit like a hangover.

OnDeck took the market by storm back on December 17th, achieving a high share price of nearly $29. If 2014 was the breakout year for alternative lending, then early 2015 is feeling a bit like a hangover.

OnDeck closed at $14.75 today, down almost 50% from its high and well below its IPO price of $20.

With stock analysts mostly bullish about the company’s prospects, retail investors may be wondering why the tide is moving in the other direction.

$ONDK weird stock sold im out..

— BullyBear13 (@BullyBear13) Jan. 22 at 09:59 AM

Q4 Earnings will be announced on February 23rd at 5pm EST. Anyone can listen in to it as the event will be webcast live on the company’s Investor Relations website or can be accessed toll free by dialing (877) 201-0168 for calls within the U.S, or by dialing (647) 788-4901 for international calls, and using conference ID 71535376.

OnDeck sailed into the market on Lending Club’s coattails just as investors were celebrating platform and marketplace lending. Lending Club is down 33% from their high.

The two have largely been lumped in together as disruptive financial technology companies, but as Stern Agee analyst Henry Coffee pointed out, OnDeck “should be considered a high-growth specialty finance lender.”

Perhaps worried that description might stick, OnDeck countered two weeks later with news that their Marketplace Platform would become generally available to institutional investors. While clearly trying to communicate what they want to be known for, investors seem skeptical.

Welp, you can now get in $ONDK under the price Tiger paid to lead the pre-ipo private round // @pkedrosky

— Justin M. Overdorff (@jmover) January 29, 2015

So is a share of OnDeck on the cheap right now? It’s hard to say. Investors seem confused by it all. That might complicate plans for CAN Capital and Prosper who are rumored to be next in line for IPOs.

Given OnDeck’s long history of losses, many will be wondering if they can reproduce the magic of 2014’s Q3, the first time they ever recorded a profit. We’ll find out on February 23rd.

—-

Note: I do not own stock or have a market position in OnDeck or Lending Club

2014 was an unbelievable year!

2014 was an unbelievable year!