Stop Being A Sub-Broker

December 10, 2015 In an industry with increasing competitive forces putting downward pressures on offer pricing, while simultaneously driving up demand for particular marketing channels (like SEO and quality data) which increases marketing costs, we are seeing massive downward pressures on profits. With this phenomenon occurring, you would have to wonder why in the world would anyone continually operate as a sub-broker today (willingly)? Are there any particular benefits to this, or is it just flat out non-sense? I wanted to explore this topic head on as we wrap up The Year Of The Broker.

In an industry with increasing competitive forces putting downward pressures on offer pricing, while simultaneously driving up demand for particular marketing channels (like SEO and quality data) which increases marketing costs, we are seeing massive downward pressures on profits. With this phenomenon occurring, you would have to wonder why in the world would anyone continually operate as a sub-broker today (willingly)? Are there any particular benefits to this, or is it just flat out non-sense? I wanted to explore this topic head on as we wrap up The Year Of The Broker.

THE VAST MAJORITY OF THE TIME, IT MAKES LITERALLY NO SENSE

There are times when I believe being a sub-broker makes some level of sense, but in my opinion those times (looking at our industry specifically) are very rare and most of the time being a sub-broker makes literally no sense based on the setup. The usual setup for a sub-broker is the same as a broker, which means you are going to be required to go out and spend money on marketing or other forms of lead generation to attract applicants.

Once you get those applications, you would forward them to the brokerage house so they can “close” the deal. A lot of sub-brokers believe this is some sort of grandiose deal, allowing them to as they say “free up time” to do other things. But this line of thinking makes literally no sense, because you have already done 98% of the work, which in our industry is just the consistent generation of high quality leads. Once you have done that and are doing that consistently, emailing the package over to a funder and chasing paperwork is the easiest part.

Why would you take only 25% – 50% of the commission structured on a deal, as well as most likely lose your ongoing renewal compensation, when you can instead take 100% of the commission, control your renewal portfolio and make renewal compensation going forward, which is the lifeblood of our industry?

LIES, LIES AND MORE LIES

Sub-brokers need to stop falling for the lies of larger brokerage houses which include the following:

“We are closers, you aren’t a closer, so let us handle it!”

This is rubbish. In our industry we don’t close, we are match-makers. The merchant comes to us looking for working capital, we pre-qualify their current standing and recommend a potential solution. If the merchant disagrees with the potential solution and we have nothing else that would work, the discussion ends. If the merchant agrees to the estimates and the product overview, we collect an application package to submit it to the funder that we believe can do an appropriately-priced deal. As long as we can get approval inline with expectations, everything moves forward on its own accord.

“We have access to special underwriting, platforms and pricing that you don’t have access to!”

More rubbish. When lenders get an A-paper deal, they give you A-paper quotes. When they get a B/C-paper deal, you get B/C-paper quotes. Look to establish a good relationship with a funder/lender. Let them know upfront that you are a small office so a smaller amount of volume will be coming through you. As long as you don’t have a high default rate, you will have access to the same systems, underwriters, base pricing, and innovative products of the funder/lender that the larger brokerage House has.

“We have access to special industry knowledge that you don’t have access to!”

More rubbish. With sources like deBanked and other popular forums, the industry has been exposed. Everything you need to know, learn and be trained on has been covered. Also the assortment of direct funder and lender blogs/websites, media publications, and all of the like covering the industry, there’s no special industry knowledge that you can’t go out and attain on your own.

YOU MIGHT NOT EVEN GET PAID

Being a sub-broker might put you in a position of not even getting paid on new deal revenue as promised, as the large (or more experienced) brokerage is fully aware of your inability to truly challenge them legally or professionally.

- Sue If You Want, It Won’t Make A Difference: You can sue the broker for the $5,000 or so that they didn’t pay you on a couple new deals in Small Claims Court. But even though you can obtain a judgment, collecting on that judgment will be nearly impossible.

- Complain Online If You Want, It Won’t Make A Difference: You can also choose to damage their reputation online through posting various negative reviews, but do you think they will care? Go on the RipOffReport all you want, the largest merchant processing ISOs are all over those reports and that doesn’t do anything to stop their growth. The organizations getting these negative reviews will just say, “we serve thousands of clients and when you are as large as us, you are bound to have unhappy customers.” And that’s exactly what the brokerage house will say to their prospective merchants who bring up these negative review listings that you made.

BUT DOES BEING A SUB-BROKER “SOMETIMES” MAKE SENSE?

On very rare occasions do I believe being a sub-broker makes sense, and it includes if there’s some sort of initial training period and if the larger brokerage has significant marketing competitive advantages.

Training

So if you have zero experience, can’t spell Merchant Cash Advance, and believe you could benefit from a 6 month period with an established broker to show you the ropes, then being a sub-broker for a short period of time could make sense. However, I still believe that with the industry being exposed the way it is, you can train yourself and have to deal with insane non-compete agreements.

Marketing Competitive Advantages

So as a small shop, your marketing budget might be limited to $1k a month, whereas the larger brokerage is spending $20k a month and in a perfect world, might give you a deal where you can work with them without being required to generate your own leads.

They’ll claim to supply everything in terms of your dialer and warm leads, with funder networks already established. So all you have to do is come in, sit down, pick up the telephone, and sell all day to the warm leads coming in from their $20k in marketing. You don’t have to do any cold-calling. So you might be getting 50 leads a week that you convert to 12 applications, which you then convert to 4 new deals. If the average funding is $30k, then that’s $120k in funding with let’s say an average 6% commission that you would split 50/50 (3%/3%), giving you $3,600 per week which is $14,400 per month.

But we don’t live in a perfect world, now do we? Do you honestly believe the structure will be established as promoted? Such as more and more of the 50 leads you receive per week turn into mainly start-ups that don’t qualify for anything. Or, most weeks you don’t receive any warm leads at all, and are required to call UCCs, aged leads, or random listings out of the Yellow Pages, which are all horrible marketing mediums.

EITHER YOU GET IN ALL OF THE WAY, OR MAYBE YOU SHOULD GET OUT

If you are going to be in this industry, then properly set up your office, marketing plan, business plan, funder network and work your own deals. Get 100% of commission structured on new deals and control your renewal portfolio (the lifeblood of our business). If you are going to operate as a sub-broker, for the most part you are going to get a raw deal as we don’t live in a perfect world. We live in a world full of inefficiencies, “rah-rah” sales motivational speeches, and promises that don’t get kept.

Fundry’s Isaac Stern Hosts Successful Fundraiser for Hatzalah of Union County

December 6, 2015 ‘Tis the season of giving for Fundry’s Isaac Stern and the dozens of folks that attended the December 5th winter fundraiser at his home in Hillside, New Jersey. The event, which served up 550 pounds of barbecue and included a Scotch taste testing bar hosted by representatives of Glenfiddich, raised over $60,000 for Hatzalah of Union County, a local non-profit all-volunteer emergency medical service organization.

‘Tis the season of giving for Fundry’s Isaac Stern and the dozens of folks that attended the December 5th winter fundraiser at his home in Hillside, New Jersey. The event, which served up 550 pounds of barbecue and included a Scotch taste testing bar hosted by representatives of Glenfiddich, raised over $60,000 for Hatzalah of Union County, a local non-profit all-volunteer emergency medical service organization.

Founded in 2004, Hatzalah EMS provides basic life support in medical emergency situations. They cover Union County NJ including the towns of Elizabeth, Hillside, Union, Roselle and Linden. Today, Hatzalah is staffed with 3 ambulances, 24 EMTs and 18 dispatchers all under the medical direction of a physician and two paramedics.

Hatzalah Chief Yudi Abraham told deBanked that Yellowstone Capital (a Fundry subsidiary) has been a long-time supporter of their organization. A few years ago, when the squad was undergoing a transition of directors, Chief Abraham reached out to Isaac Stern for financial help. At the time, Hatzalah was in serious need of replacing an older ambulance as well as covering monthly operating expenses. “Isaac didn’t waste any time and sprang right into action,” says Chief Abraham. “He immediately convened his employees and his associates and came through for us in a huge way.” Yellowstone Capital raised the funds in under two days for Hatzalah to buy a fairly used ambulance. Ever since then, Stern and Chief Abraham have been working closely together to ensure that other expenses were covered. Over the years, Yellowstone Capital has helped donate the funds to purchase two additional ambulances that currently make up Hatzalah’s fleet. The Yellowstone Capital name appears on the side of each of them.

The most recent event kicked off with a $10,000 personal donation from Stern, prompting others to give too while enjoying the festivities.

“With the help of Yellowstone Capital we are able to maintain our level of service and continue providing the best possible emergency care for our patients,” said Chief Chaim Cillo. “We at Hatzalah will forever be most appreciative for such an incredible company that cares and gives back to the community in such a large way.”

Stern and Yellowstone were also presented an award for their continued generosity.

Chief Yudi Abraham (left) and Fundry CEO Isaac Stern (right)

Chief Yudi Abraham (left) and Fundry CEO Isaac Stern (right)In attendance at the event were Fundry employees, friends, family members, and others from the non-bank finance industry.

From left to right: Andrew Hernandez of Central Diligence Group, Sean Murray of deBanked, and Andy McDonald of Yellowstone Capital/Fundry

From left to right: Andrew Hernandez of Central Diligence Group, Sean Murray of deBanked, and Andy McDonald of Yellowstone Capital/Fundry

Michael Samuels (left) and Steve Weinrib (right) both of Yellowstone Capital/Fundry

Michael Samuels (left) and Steve Weinrib (right) both of Yellowstone Capital/FundryHatzalah means “rescue” or “relief” in Hebrew and for many guests the event fell on the eve of the Hanukkah holiday. The volunteer EMS crew of course helps all people in need of care.

“Our pay,” said Chief Abraham, “is helping our patients and saving lives.”

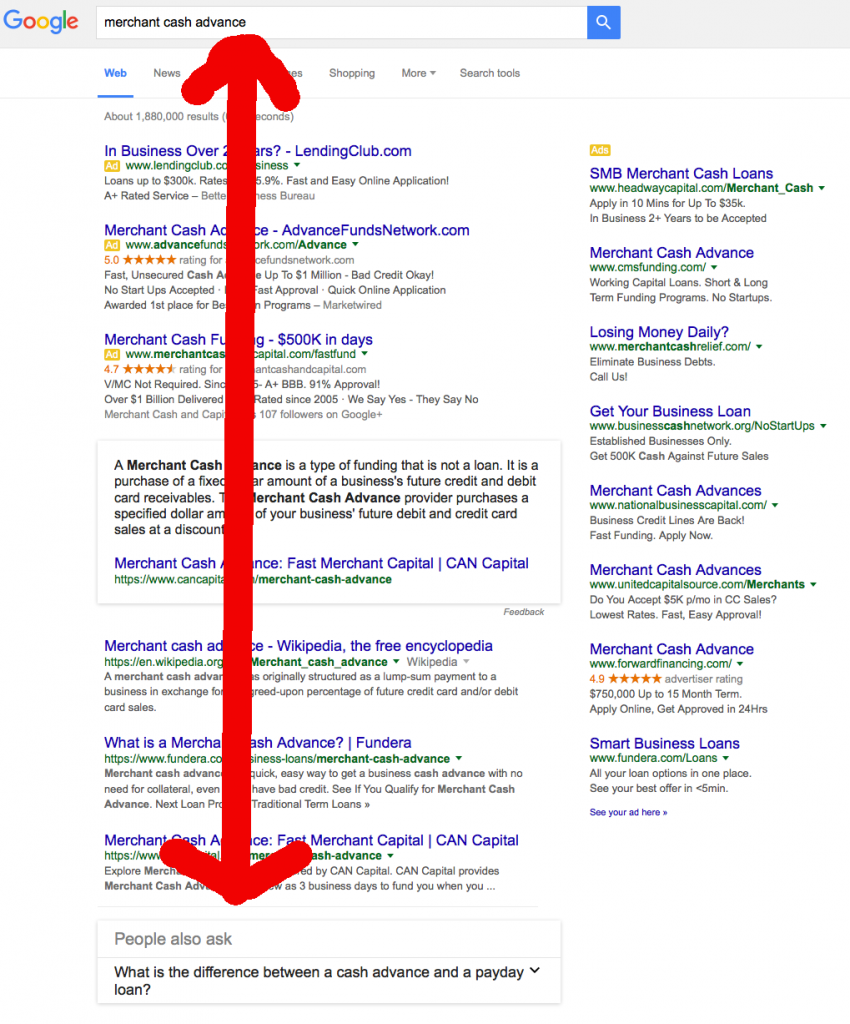

Google Serves Low Blow to Merchant Cash Advance Seekers

December 2, 2015 Almost eighteen months ago, I explored whether or not Google was rigging the search results to benefit two lending companies they had equity investments in, Lending Club and OnDeck. At the time, both companies ranked at the top for highly coveted keywords even if they weren’t directly related to the user’s search query.

Almost eighteen months ago, I explored whether or not Google was rigging the search results to benefit two lending companies they had equity investments in, Lending Club and OnDeck. At the time, both companies ranked at the top for highly coveted keywords even if they weren’t directly related to the user’s search query.

Now that those two companies are public, a company called Credit Karma seems to have inherited the top spots. And wouldn’t you know it, Google has also invested in them.

Google: loans

Google: personal loan

But that’s not the worst of it. Thanks (or no thanks rather!) to a relatively new search result feature called “People Also Ask,” one keyword recently started serving up results with a different kind of hidden agenda.

While my captured results may not be identical for everyone, I have conducted tests with other people on other devices and from other areas and it was present each time. With this box, Google is subtly planting the negative seed that payday loans and merchant cash advances are basically so identical that other people just like you are wondering what the difference between the two are. But here’s the rub, the two have nothing to do with each other and it’s unlikely so many people are asking that.

Pay no mind to the fact that the box makes reference to a “cash advance” not a “merchant cash advance.” The painstaking mishap could be innocently chalked up to an algorithmic error if only googling just cash advance revealed the same box in the results. But it doesn’t. Only merchant cash advance brings this up.

Comparing merchant cash advances to payday loans is straight out of the anti-merchant cash advance propaganda playbook. At least one Google-owned business lending company is actively lobbying against short term business lending and merchant cash advances in Washington so the placement and comparison of the People Also Ask box in their results is highly suspicious.

It’s no secret that Google is also directly lobbying in the online lending space too. One month ago, right before Google magically started to suggest to searchers that merchant cash advances and payday loans were related, Google formed a lobbying organization called Financial Innovation Now with Amazon and Apple. On their main agenda is online lending.

Given the suspicious search rankings for companies they have an equity stake in, I would not doubt for a second that something like this was manually inserted. I admit that my evidence and my case are weak, but given the circumstances, it’s quite possible there’s something deliberate happening here.

What do you think? Do you see this when you google merchant cash advance?

Merchant Cash Advance | A Look Back and Plan Forward

November 29, 2015 Merchant Cash Advance is still a relatively unknown term and product to the masses, but amongst most of its target customer base, it definitely has a stigma that is rightly deserved in some ways, but I believe that it is also misunderstood in many other ways. Having been in the industry for nearly 10 years, I can say that I have seen my fair share of positive and negative events as they relate to the industry, but I believe that it has all been for its betterment and growth. Furthermore, by having been on the underwriting side for a majority of that time, I can say with great certainty that I have seen this product help several small business owners over the years, and it will continue to do so as the stigma fades away and acceptance increases.

Merchant Cash Advance is still a relatively unknown term and product to the masses, but amongst most of its target customer base, it definitely has a stigma that is rightly deserved in some ways, but I believe that it is also misunderstood in many other ways. Having been in the industry for nearly 10 years, I can say that I have seen my fair share of positive and negative events as they relate to the industry, but I believe that it has all been for its betterment and growth. Furthermore, by having been on the underwriting side for a majority of that time, I can say with great certainty that I have seen this product help several small business owners over the years, and it will continue to do so as the stigma fades away and acceptance increases.

For those of us working in this industry now, let’s face it – most small business owners that have taken a merchant cash advance or have been solicited for the product would much rather go to their bank for the money. The problem, as many merchants have come to realize in recent years, is that lending in general essentially dried up after the recession. The faucet is now running again, but small businesses were all but forgotten. Only the most well qualified borrowers are able to obtain the desired amount of capital needed at a reasonable cost through traditional bank loans. In addition to meeting all of the necessary criteria for a bank loan or line of credit, a borrower must also be prepared to wait months for the process to be finalized.

The days of a small business owner being able to go down to his or her community bank or local branch for a quick cash injection are long gone, but that’s where we come in. We are catering to a customer base that has been left out to dry. We are dealing in a marketplace that is grossly underserved by the larger financial institutions. We are charging a premium for taking on risk that most cannot stomach. We are keeping America running. That might sound ambitious, but is realistic when you put things in perspective.

SBA and IDC data show that small businesses employ at least half of the US workforce and produce anywhere from 60% – 80% of the new jobs annually while also accounting for nearly half of total US private payroll. As if that weren’t enough, small businesses also produce six trillion dollars or over 50% of all non-farm GDP in the US. When looking at additional SBA data which also states that more than 80% of all small businesses need to use some sort of financing to grow their business, it’s perplexing as to why banks have turned their backs on the people that have put America on their very own backs.

However, I do not want to go into great detail or make any assumptions on why “big banks” are not lending to small businesses. Rather, I would like to take some time to focus on how we can continue to support the growth of small businesses across America. The MCA product in particular has evolved quite a bit over the past 10 years, but a lot of that development has taken place in the past 3-5 years, and the industry has grown leaps and bounds as a result. When I started working as an underwriter several years ago, there were less than 10 lenders and 50 brokers operating within the space. Nowadays, there are hundreds on both sides of the fence, and there are multiple new entrants every day – senior guys starting their own operations, one man rogues from the insurance and mortgage businesses, consumer payday lenders, et cetera. – all looking for our piece of the pie, but who out there is really looking to improve upon and grow the product for the better?

I suppose therein lies the problem. Unfortunately, the tremendous growth we have recently witnessed also comes with a flood of unqualified and unknowledgeable management and staff that are simply following the direction of their unqualified and unknowledgeable employers. As an industry, if we expect to continue making headway in the small business lending environment, we must first better ourselves by taking the time to learn and understand the product in order to better educate our customers. If you know me, you have heard me say on a few occasions that it is easy to put the money on the streets, but the problem for most people is getting it back.

I suppose therein lies the problem. Unfortunately, the tremendous growth we have recently witnessed also comes with a flood of unqualified and unknowledgeable management and staff that are simply following the direction of their unqualified and unknowledgeable employers. As an industry, if we expect to continue making headway in the small business lending environment, we must first better ourselves by taking the time to learn and understand the product in order to better educate our customers. If you know me, you have heard me say on a few occasions that it is easy to put the money on the streets, but the problem for most people is getting it back.

As with anything in life, you cannot jump into something and expect to master it. Over time, you get a grip of what you are doing, and you begin to build on that understanding. Therefore, no one should enter the market expecting to make huge returns without learning the ins and outs of the business. I, along with several of my peers, have seen plenty of well-intentioned but aggressive entrants “lose their shirts,” so to speak, because they did not do the proper diligence on the industry or the actual diligence required to operate within the space. Lending money with only a UCC-1 in place only on future receivables or sometimes no collateral at all is risky business as it is, but not taking the necessary steps to mitigate that risk is only asking for a rough road ahead – not only for the lender itself, but also for their potential clients, brokers, other lenders, and the industry as a whole.

Our underwriters and sales people, in addition to management, should have a solid understanding of the product they are working on. They should be able to educate customers as well as their peers. Transparency throughout the process is key for maintaining a long and mutually benefiting relationship with the client. By having this firm grip and understanding of the product, we reduce the risk of an unsatisfied customer. As with the mortgage and insurance industries, sales and underwriting must work together to determine the best possible result for both the client and the company. This is definitely a challenge for most groups due to the amount of balancing required to meet the needs of the company, but by establishing best practices and procedures in both the sales and underwriting processes, we can begin to think and work within separate verticals and group goals but streamline the process to achieve the agenda of alternative small business lending which should be to help provide small business owners with the fast and efficient capital they need.

Whether you have been in the industry for years, you have just joined this year, or you are considering taking the dive now, it’s only fitting that at this time of year we give thanks to those small business owners and celebrate their entrepreneurial spirits because they are the reason we, ourselves, are currently employed. But more importantly, they are setting us up for quite an adventure which will change the landscape of small business lending for good. I, personally, cannot wait for the next 3-5 years of continued growth because I can only see a bright future if we are able to collectively educate ourselves and pass that knowledge along to our clients. As long as the proper steps to learn have been taken, the competition from new entrants mentioned previously is also welcomed because this further drives new ideas and developments within the space – new financial products to offer clients, lower costs, and most importantly easier and efficient access to quick capital for the busy small business owners constantly on the go in an effort to grow their business while putting the rest of us on their backs.

Business Lending: Sell The Whole Solution

November 26, 2015 The year of 2015 went by rapidly, as it felt like yesterday that I was sitting back in my office chair, reading an article from the March/April 2015 edition of deBanked Magazine, composed by Ed McKinley, a man with nearly 40 years of journalism experience.

The year of 2015 went by rapidly, as it felt like yesterday that I was sitting back in my office chair, reading an article from the March/April 2015 edition of deBanked Magazine, composed by Ed McKinley, a man with nearly 40 years of journalism experience.

McKinley began a discussion about a “year of the broker,” based on analysis, interviews, and criticism of the mass new entrants of brokers into our space within recent times. I have spent the better part of this year continuing this discussion both here on deBanked and within our industry circle, with discussions that have been both conventional, out of the box, and even at times peculiar. Speaking of peculiar, this brings us to the opening of this discussion, in which I must quote RuPaul.

RuPaul once stated that, “life is about using the whole box of crayons.” In my opinion, if you can figure out the profession of sales, you can pretty much figure out most of everything there is to life. And if RuPaul is right in that life is about using the whole box of crayons, why do so many of the mass new entrants of brokers within our industry, believe they are going to properly sell a merchant without using the whole solution?

It’s common knowledge that every individual crayon provides its own distinctive color, which in and of itself creates its own distinctive value, as value in this case is based upon where the color fits on the page to provide its role in the total coloring scheme. But just like crayons, every part of our alternative financing solution provides a distinctive value that altogether creates the whole solution for the merchants we serve.

(Q) + (S) + (P) = THE WHOLE SOLUTION

The Whole Solution equation is based on three letters. “Q” stands for Quality, “S” stands for Support and “P” stands for “Pricing”. How many brokers within our industry focus only on offering the “Q” and “S” portion of this equation, without the “P” portion? How many brokers within our industry focus on offering the “Q” and “P” portion, without the “S” portion?

QUALITY

Quality is all about bringing to the merchant what they deem to be value, and in our space (alternative financing) that means capital when they need it. Thus, you should have a comprehensive resource network of alternative financing products from merchant cash advances, alternative business loans, equipment leasing products, factoring, purchase order financing, and more, with approval amounts that can solve the working capital needs of the merchant. This creates value.

SUPPORT

This is all about your professional competency, merchant servicing and merchant education.

- Professional competency is all about you and your team having knowledge of the industry, the various products, the competing products, the market trends, understanding your merchant’s industry, and understanding how the product could help (or hurt) the merchant in achieving their operational objectives.

- Merchant servicing is all about providing tools for your merchant to manage their account with you, such as online access to statements, balances, transactions, or at least providing such information in a monthly statement. It also includes having easy access to live support agents during business hours to properly handle merchant questions, payment issues, collection issues, as well as there being an option for payment modification if a situation warrants it.

- Merchant education is all about educating the merchant based on the big data analytic information that you have currently, and how they can use this to help their business in various areas such as how to qualify for more conventional financing, better marketing strategies, etc.

PRICING

In our industry, proper pricing is based on utilizing risk-based pricing, which is to price a merchant based on their paper grade. This can only be done after efficient pre-qualification of the merchant to understand where they stand.

Some merchants have low risk measurement, thus, they are A+ Paper and A Paper. Some merchants have moderate levels of risk, thus, they are B and C Paper. Then some merchants have higher levels of risk, thus, they are D and E Paper.

A+ Paper: Should be priced similar to a P2P lender’s pricing schedule, which includes longer terms up to 60 months. These terms and conditions mirror that of a conventional loan.

A Paper: Should be priced on 6 – 18 month payback cycles. The shorter ranges of 6 – 8 months having 1.09 – 1.20 pricing, 9 – 10 months having 1.22 – 1.24 pricing, 12 – 15 months having 1.25 – 1.32 pricing, and 18 months having 1.28 – 1.35 pricing.

B and C Paper: Should be priced on 6 – 12 month payback cycles. The shorter ranges of 6 – 8 months having 1.22 – 1.26 pricing, 9 – 10 months having 1.28 – 1.30 pricing, and 12 months having 1.35 – 1.45 pricing.

D Paper: Should be priced on 4 – 7 month payback cycles. 4 – 5 months having 1.28 – 1.35 pricing and 6 – 7 months having 1.40 – 1.45 pricing.

E Paper: Too high of risk to usually find a decent approval.

FINAL WORD

I usually debate other sales professionals (within our industry and outside of it) in regards to selling the whole solution.

Some believe that if you put majority of the focus on quality and support, then you can literally price your client however you prefer, including well above their marketplace pricing.

Some believe that if you just focus on providing the lowest price, then you can get away without having the best quality and support functions.

Both of these approaches are selling the partial solution, but the whole solution should always be the best solution as it provides the best in quality and support, while tying in a proper pricing model for the client based on their standing in the marketplace. This leads to client longevity, loyalty and stickiness. That’s why I believe the best approach is to sell the whole solution.

Merchant Cash Advance APR Debate (Sean Murray v Ami Kassar)

November 24, 2015The other day, Inc. writer and loan broker Ami Kassar took some time out of his day from taking photos of his shadow in the park to engage me in a debate about the use of APRs in future receivable purchase transactions. He was apparently very bothered by my analysis of Square’s merchant cash advance program which has transacted more than $300 million to date.

To clarify my position here, I am indeed in favor of transparency, so long as it’s intelligent transparency. Coming up with phony percentages based on estimates and applying them to transactions where they don’t make sense is not transparency. Similarly, advocating that merchant cash advance companies and lenders alike move away from a dollar-for-dollar pricing model to one that requires the seller or borrower to do math or hire an accountant is also not transparency.

Even a Federal Reserve study that attempted to prove merchant cash advances were confusing inadvertently proved that APRs in general were confusing. If someone doesn’t know how to calculate an APR, then it’s unreasonable to assume that they could work backwards from an APR to determine the dollar-for-dollar cost of capital. In effect, APR is a surefire way to mask the trust cost despite arguments to the contrary.

My unplanned debate with Ami Kassar on twitter is below:

Sorry Ami. The only thing unclear is your argument.

Building An Alternative Lending Sales Profile

November 24, 2015 Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the word, independent, in a number of different ways, but one of the definitions provided relates this word to the concept of freedom. Most of us operate in this industry on an independent basis, which gives us a significant level of freedom that revolves around not having a boss, freedom to set our own schedules, freedom from being down-sized, freedom from office politics, but more importantly:

Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the word, independent, in a number of different ways, but one of the definitions provided relates this word to the concept of freedom. Most of us operate in this industry on an independent basis, which gives us a significant level of freedom that revolves around not having a boss, freedom to set our own schedules, freedom from being down-sized, freedom from office politics, but more importantly:

- freedom to craft our own business plans

- freedom to target our own market segments

- freedom to decide what we will sell

- freedom to create our own products

- freedom to negotiate our own market pricing

- … and freedom to innovate

With such high levels of freedom, you have to wonder why a lot of brokers in our industry don’t exercise such liberties? Why do we sell the same products (cash advances and alternative business loans)? Why do we use the same marketing tactics (UCCs and aged leads)? Why do we market, promote and sell to the same merchants (UCCs)? Why do we use the same “pitch”? Why do we submit to the same funders?

If we are truly independent contractors, why do we all look, act and sound the same?

As we continue The Year Of The Broker, I wanted to begin a discussion on a concept that integrates your capability of independent expression. It’s the concept of constructing an alternative financing sales profile. It allows you to display your level of true independence by pre-qualifying your prospective clients and recommending solutions that are different from the pack of brokers recommending the same “me too” solutions, seeking to submit the merchant to the same “me too” funders.

ARE YOU A “BROKER” OR NOT?

Are you paid only when you broker (fund) a deal?

If so, the generation of a financing lead or application in and of itself, doesn’t produce value as it doesn’t create revenue. Revenue is only created when you successfully broker a deal, which is to match a merchant with alternative funding needs and with a particular terms/conditions comfort range, with products funded by lenders whose pricing lines up with the particular comfort level of your prospective client.

As a broker, you are much more than a salesperson, you are more of a match-maker, an arbitrator, and an consultant. You can’t consult someone if you don’t know their current situation for one, and two, you can’t consult someone unless you have the resources to prescribe appropriate solutions.

See yourself more as a doctor than a salesperson, where as a salesperson has one or two products that he’s looking to “push” on a prospect using various tactics such as cost cutting and overcoming objections, a doctor isn’t trying to “push” anything out of the gate without firstly diagnosing the client through a series of questions. After said questions have been inquired and answers provided, the doctor creates a “profile” of said client and through his wealth of medication, he prescribes a couple of solutions to assist the client.

To help increase your chances of brokering (funding) your deals, you want to increase your level of pre-qualification and increase your level of product offerings, both of which will allow you to create firstly an alternative financing sales profile of your client, and then secondly allow you to go into your wealth of alternative financing products to prescribe an array of products.

EFFICIENT PRE-QUALIFICATION

Going forward, make sure to do serious pre-qualification to create an estimated risk profile as well as an estimated sales profile. You want to know all of the following: their credit, time in business, annual sales, cash flow situation, level of profitability, type of assets, outstanding commercial debt, any current tax or judgment liens, recent bankruptcies, and current status of commercial mortgage or commercial lease agreements.

From this information you are able to create an Alternative Financing Sales Profile along with an occupying Risk Profile for each product you will soon be recommending, to know which lender within that product category is best to serve your client.

YOUR WEALTH OF ALTERNATIVE FINANCING RESOURCES

So for example, say we have a restaurant owner that’s in need of $250k in working capital for expansion. You shoot him over the pre-qualification survey and receive the following: 700 FICO, 5 years in business, $1 million sales, zero NSFs/Overdrafts for 6 months, $10k average bank balances over the last 6 months, company has been profitable for the last 3 years, no tax liens, no judgment liens, no bankruptcies, current on commercial lease payment, outstanding debt that includes $25k on a credit card with $50k outstanding on a bank loan. The merchant’s commercial assets includes business equipment, free and clear, with appraised value of $150k.

As an alternative financing broker, you should have access to more than just merchant cash advances and alternative business loans, you should also have access to: merchant processing, equipment leasing, asset based lines of credit, inventory loans, SBA loans, business credit cards, factoring, purchase order financing, commercial mortgages and real estate hard money loans.

So based on the answers to the pre-qualification survey completed by the restaurant owner, in conjunction with his total financing needs, you might be prescribing an SBA loan, a merchant cash advance, and a sale-leaseback.

- You would seek to get him an SBA loan first and let’s just say he only gets approved for $50,000. So you guys complete the process to fund the SBA loan.

- Next, you would look at doing either a merchant cash advance for let’s say another $100,000 using split funding. You notice that his current processing rates are a little higher than market average pricing for Restaurants and show him a savings analysis with your interchange plus pricing structure with a 10BP mark-up that should be saving him $400 a year which is $1,200 over three years. So in the process of this you also convert his merchant processing over to one of your processing platforms that can handle split funding. Now you have raised $150,000 of the $250,000 funding goal that the merchant has in mind.

- Finally, you would look at doing a sale-leaseback on his pre-owned equipment that’s appraised for $150,000. With a 70% LTV, this comes to $105,000 in funding. Now you have successfully funded the merchant over $250,000 and in the process closed three different alternative funding products as well as converted over his merchant processing at the same time.

In an upcoming article, I will continue this discussion on pre-qualification by going into information on how this level of efficiency includes the creation of Risk Profiles that allow you to limit your submissions to your funders/lenders as to not clog up their underwriting pipelines with unnecessary submissions. It allows you to focus on submitting 10 applications and funding 5, instead of submitting 50 applications and funding 5.

Merchant Cash Advance is The Real Square IPO Story

November 22, 2015 Square’s debut on the New York Stock Exchange is being talked about as one of the more consequential IPOs of 2015. As a mobile payments company famous for both losing money and its founding by Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s CEO, the $2.9 billion valuation pales in comparison to its rival First Data that went public just a month before. First Data, which was founded in 1971, is worth five times more than Square with a market cap of $14.7 billion to Square’s $2.9 billion. But it’s Square that everyone’s talking about and not necessarily in a positive way. Cast as the poster child for runaway private market valuations in Fintech, Square’s Series E round just a year before had supposedly increased its worth to $6 billion.

Square’s debut on the New York Stock Exchange is being talked about as one of the more consequential IPOs of 2015. As a mobile payments company famous for both losing money and its founding by Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s CEO, the $2.9 billion valuation pales in comparison to its rival First Data that went public just a month before. First Data, which was founded in 1971, is worth five times more than Square with a market cap of $14.7 billion to Square’s $2.9 billion. But it’s Square that everyone’s talking about and not necessarily in a positive way. Cast as the poster child for runaway private market valuations in Fintech, Square’s Series E round just a year before had supposedly increased its worth to $6 billion.

Robert Greifeld, the CEO of Nasdaq, had warned people just weeks earlier about the validity of private market valuations. “A unicorn valuation in private markets could be from just two people,” he said. “Whereas public markets could be 200,000 people.”

And while Square’s IPO was relatively well-received, closing at 45% above its offered price, there’s an entire story beyond payments hidden in the company’s financial statements under the label of “software and data products.” That’s code for merchant cash advance, the working capital product they offer to customers that currently makes up 4% of the company’s revenue.

“Since Square Capital is not a loan, there is no interest rate,” states the company’s FAQ. That echoes what dozens of other merchant cash advance companies have been saying for a decade. “You sell a specific amount of your future receivables to Square, and in return you get a lump sum for the sale,” marketing materials explain.

Lenders that don’t approve of this receivable purchase model are lobbying politically against it, some of whom are well-known. Lending Club for example, is a signatory to the Responsible Business Lending Coalition’s Small Business Borrowers Bill of Rights (SBBOR), committing themselves to things like transparency and the disclosure of APRs even for non-loan products.

But disclosing an APR on a receivable purchase merchant cash advance transaction is not only impossible since there is no time variable, but would violate the spirit of the contract even if estimates were used to fill in the blanks. Nonetheless, Fundera CEO Jared Hecht, whose marketplace platform has also signed the SBBOR told Forbes in September that “small business owners have been sold by pushy salespeople, hiding terms, disguising rates and manipulating customers into taking products that aren’t good for them.”

But disclosing an APR on a receivable purchase merchant cash advance transaction is not only impossible since there is no time variable, but would violate the spirit of the contract even if estimates were used to fill in the blanks. Nonetheless, Fundera CEO Jared Hecht, whose marketplace platform has also signed the SBBOR told Forbes in September that “small business owners have been sold by pushy salespeople, hiding terms, disguising rates and manipulating customers into taking products that aren’t good for them.”

Ironically, Fundera’s own merchant cash advance partners have not made any such pledge to disclose APRs. No one’s commitment is verified anyway. “Neither Small Business Majority nor any other coalition member independently verifies that any of these signatory companies or entities in fact abide by the SBBOR,” the group’s website states. This isn’t to say that their intent is misguided, there’s just very little substance to it below the surface.

For example, while the coalition has made some subtle and not so subtle digs about merchant cash advances over fairness and transparency, it’s the lending model used by some of the SBBOR’s signatories that is being challenged by the courts right now. Because of Madden v. Midland, Lending Club’s practice of using a chartered bank to originate loans could potentially be in jeopardy. The ruling was just appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. At the heart of the issue is the ability to usurp state usury caps through the National Bank Act. For a company that has pledged to offer non-abusive products, it’s ironic that their model relies on preemption of state interest rate caps all the while reassuring their shareholders that there’s no risk because of their Choice of Law fallback provision. In truth, Lending Club uses a state chartered bank and not a nationally chartered bank and thus would be somewhat shielded in an unfavorable Supreme Court ruling.

Those concerned in years past that receivable purchase merchant cash advances were full of regulatory uncertainty had shifted towards the model that Lending Club uses since it was perceived to have more nationally recognized legitimacy. However, with that model seriously challenged, old school merchant cash advances are once again looking pretty good. That’s probably why publicly traded Enova International Inc. (NYSE:ENVA) bought The Business Backer this past summer. And it’s why Square skated through their IPO without much resistance to their merchant cash advance activities.

The story of Square was either that it was overvalued, that CEO Jack Dorsey couldn’t handle running two companies, that they were losing money, or that their deal with Starbucks was a mistake. Meanwhile Square has processed $300 million worth of merchant cash advances, a product that doesn’t disclose an APR since it’s not a loan. “Nearly 90% of sellers who have been offered a second Square Capital advance cho[se] to accept a repeat advance,” their S-1 stated.

“If our Square Capital program shifts from an MCA model to a loan model, state and federal rules concerning lending could become applicable,” it adds. And right now partly due to Madden v. Midland, the loan model looks pretty shaky. Square proved many things when they went public on November 19th and one was that merchant cash advances are just the opposite of what critics have argued in the past.

Battery Ventures’ general partner Roger Lee told Business Insider, “the [Square Capital] product itself will have unique advantages in the market, and it’s a big market.”