p2p lending

Legal Brief: Madden v. Midland Funding

June 11, 2015Madden v. Midland Funding, 2015 U.S. App. LEXIS 8483 (2nd Cir. May 22, 2015).

This is an interesting case for the alternative lending industry that deals with the interplay between the National Banking Act and New York State’s usury laws.

This is an interesting case for the alternative lending industry that deals with the interplay between the National Banking Act and New York State’s usury laws.

The plaintiff borrower opened a credit card account with a national bank, Bank of America (“BoA”). BoA sold the account to another national bank, FIA. FIA subsequently sent a change of terms notice stating that, going forward, the plaintiff’s account agreement would be governed by the law of Delaware, FIA’s home state. FIA later charged off the account and sold it to a third-party debt purchasing company, Midland. FIA did not retain any interest in the account after selling it to Midland and Midland was not a national bank.

Midland attempted to collect on the account and sent the plaintiff a demand letter indicating that there was a 27% interest rate on the account. Plaintiff sued Midland, alleging violations of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act and New York’s criminal usury laws. New York law limits effective interest rates to 25 percent per year. The parties agreed that FIA had assigned plaintiff’s account to Midland and that the plaintiff had received FIA’s change in terms notice. Based on the agreement, the trial court held that the plaintiff’s state law usury claims were invalid because they were preempted by the National Bank Act.

The National Bank Act supersedes all state usury laws and allows national banks to charge interest at the rate allowed by the law of the bank’s home state. Midland argued that, as FIA’s assignee, it was permitted to charge the plaintiff interest at a rate permitted under Delaware law. FIA was incorporated in Delaware and Delaware permits interest rates that would be usurious under New York law.

On appeal, The Second Circuit Court of Appeals noted that some non-national banks, such as subsidiaries and agents of national banks, might enjoy the same usury-protection benefit as a national bank. However, third-party debt buyers, such as Midland, are not subsidiaries or agents of national banks. Midland was not acting for BoA or FIA when it attempted to collect from the plaintiff. Midland was acting for itself as the sole owner of the debt. For this reason, the Second Circuit held that Midland could not rely upon National Bank Act preemption of New York State’s usury laws.

Is the Premium Gone in Peer-to-Peer Lending?

June 10, 2015FDIC insured 5-year CDs are now paying as high as 2.25% APR. Compare that against 5-year notes offered by Lending Club and Prosper that will pay ___________.

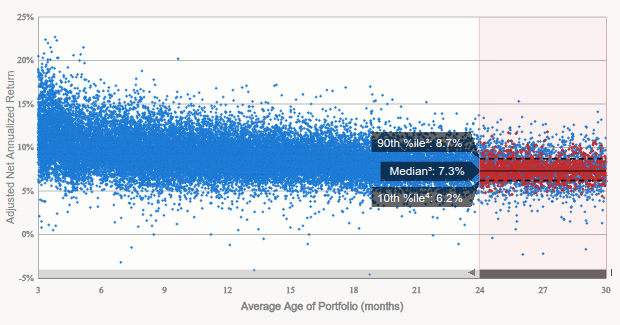

According to Lending Club, the average 2-year aged portfolio is yielding an average return of 6.2% to 8.7%. On loans maturing in 5 years, the numbers will be even lower. With peer-to-peer (P2P) lending being all the rage over the last few years, these returns look surprisingly benign.

Did something change?

According to Simon Cunningham’s LendingMemo analysis, investor returns have fallen almost 2% in two years. Cunningham wrote, “In 2014 something changed. Lending Club began to lower interest rates without adjusting FICO at all. Basically, for the first time in their company’s history they began to decrease the reward for investors without decreasing the risk.”

FICO stayed the same and rates came down, a move that was intentional and rationalized by Lending Club CEO Renaud Laplanche when he said, “By [lowering interest rates] we believe we can generate more positive selection. For example, this means people who now take a 10% loan offer, but who would have rejected a 12% offer, are typically also higher quality borrowers. So the belief is that part of the rate cut will be absorbed by lower defaults.”

Ironically, online business lender OnDeck, who has also lowered interest rates, might disagree with that psychology. Back on their Q4 2014 earnings call, OnDeck CEO Noah Breslow reported that their borrowers were basically taking the first offer they could get because of the time and stress associated with continuing the search.

For Lending Club, their gamble could mean that someone that would’ve taken a 12% offer is now taking a 10% offer even though they would’ve taken a 12% offer or a 15% offer or an 18% offer. Instead they are worried that borrowers will choose nothing if a loan is perceived to be too expensive. This experiment has wreaked havoc on investor yields.

“Folks shouldn’t enter this investment assuming a 7% return when they actually go on to receive 5.5%,” wrote Cunningham. He goes on to explain that average investor returns could go as low as 3.7%.

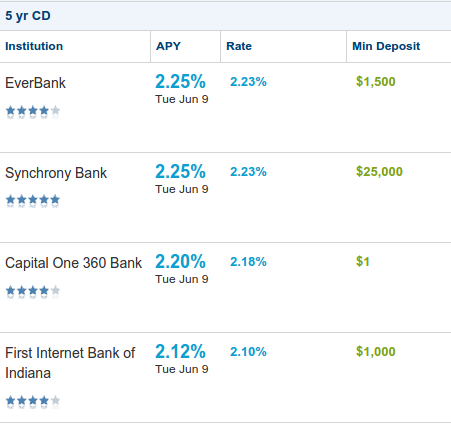

The price of risk

If you’ve been earning 0% in your savings account for the last few years, the returns in P2P have likely been a welcome reprieve. But as the probability that that Fed will soon raise rates increases, so too have riskless yields. According to bankrate.com, FDIC insured 5-year CDs are now paying as high as 2.25%, a figure that’s only 1.45% to 3.25% lower than Cunningham’s P2P estimates. Is the spread commensurate with the risk?

If you’ve been earning 0% in your savings account for the last few years, the returns in P2P have likely been a welcome reprieve. But as the probability that that Fed will soon raise rates increases, so too have riskless yields. According to bankrate.com, FDIC insured 5-year CDs are now paying as high as 2.25%, a figure that’s only 1.45% to 3.25% lower than Cunningham’s P2P estimates. Is the spread commensurate with the risk?

Previously, I’ve explained that Lending Club is not actually a middleman in a marketplace. No matter which notes an investor buys, they are in fact lending money to Lending Club itself. None of the notes matter if Lending Club goes bankrupt. An investor might as well be buying stock in the company.

Furthermore, none of the yield projections take into account a swift and brutal recession or a landmark legal ruling that could jeopardize an entire portfolio overnight. The loss of risk in Lending Club notes is your entire investment. It’s not just about the potential for low yield or negative yield. There is an inherent risk of total loss.

On a $100,000 investment, the added premium for a very risky asset over a riskless asset is potentially about $1,450 to $3,250 a year. Or is it?

Taxing away the premium

As loans default, investors might think they can offset the interest with their losses. That’s not the case because the interest is counted as normal income and the losses as capital losses. That means the losses can only be offset by capital gains income from other investments.

As loans default, investors might think they can offset the interest with their losses. That’s not the case because the interest is counted as normal income and the losses as capital losses. That means the losses can only be offset by capital gains income from other investments.

Therein lies the problem for an investor that has no capital gains. In that case, the IRS only allows individuals to deduct up to $3,000 in losses*. If someone is not investing outside of P2P lending, they’re at a big disadvantage.

Without capital gains, an investor could end up with this situation:

$10,000 in Lending Club interest income and $5,000 in Lending Club losses would result in being taxed on $7,000 in income (3k deduction limit). Talk about a yield killer.

With capital gains, any amount of losses can be offset against them.

On the Lend Academy forums, investors have hypothesized scenarios where the $3,000 limitation could lead to net yields below 1%!

To a relatively serious investor, the premium earned for investing in a very risky asset can be entirely wiped out by a tax limitation. Strangely then, the net dollar reward in a 5-year FDIC insured CD could potentially be the same as buying exotic consumer lending notes where total loss is very plausible. In that case, the notes offer no rational sense to invest in.

Indeed many P2P investors on the Lend Academy forums have reported plans to close their accounts or to invest only through IRAs where the tax rules are different.

Another tax

With P2P lending still a relatively young and confusing industry, a small retail investor may require the help of an accountant to prepare their returns, especially if they used folio where notes can be traded. Be aware that the hourly rate of tax preparation will cut into gains earned in P2P.

What’s in it for investors?

2.25% isn’t a very enticing offer, but neither is 5.5% if that’s the estimated figure barring any legal setbacks, bad recession, company failure, and tax consequences. As the economy prepares itself for an eventual increase in rates, the returns on savings accounts and CDs will rise over time. And yet Lending Club is curiously moving in the opposite direction. That’s great for borrowers, bad for investors.

The point at which it will no longer make economic sense to invest in P2P is eerily just around the corner if it’s not here already…

Bless You, Fund Me: What Words Predict About Loan Performance

June 7, 2015 Way back in 2006 when I was just a baby merchant cash advance* underwriter, I encountered a book store that was borderline qualified. The final phone interview would make or break their approval so I grabbed my pen and paper and dialed their number.

Way back in 2006 when I was just a baby merchant cash advance* underwriter, I encountered a book store that was borderline qualified. The final phone interview would make or break their approval so I grabbed my pen and paper and dialed their number.

I went through the checklist of questions and they passed. But what really convinced me that it was a deal worth doing was the amount of times the owners made references to God. They were clearly religious people which indicated to me that they were probably also of high moral character. It didn’t matter what religion it was or if their beliefs aligned with mine, I was simply captivated by their values.

After approving the deal and funding them, they actually mailed me a handwritten letter to express their gratitude. It concluded with, “God Bless You!” and I hung it up on the wall of my cubicle to remind myself of the good I was doing for small businesses.

A few weeks later, the payments stopped. All of their contact numbers were disconnected and the owners of the store could not be located. They completely disappeared along with almost all of the money. Looking up at the note on my wall, a shiver went up my spine. Had I been duped? And did they use religion as a tool to influence my decision?

I thought that surely they must’ve encountered legitimate financial difficulty but I believed that even if so, people with their values would’ve been more forthcoming about it. Instead they just took the money and split and were never heard from again.

I learned a lesson about being emotionally influenced on a deal and it turns out there were clues this outcome might happen all along.

Bless you

In a study titled, When Words Sweat: Written Words Can Predict Loan Default, Columbia University professors Oded Netzer and Alain Lemaire, and University of Delaware professor Michal Herzenstein analyzed the text of more than 18,000 loan requests made on Prosper’s website. Applicants that used the word God were 2.2x more likely to default on their loans. And the phrase Bless you correlated higher on the default scale as well, though not as high as other non-religious words.

On the list of words more likely to be mentioned by defaulters are, I promise, please help, and give me a chance. Statistics actually show that someone promising to pay is less likely to pay than someone that doesn’t explicitly promise.

Among the other more common words likely to be mentioned by defaulters is hospital. This word holds special significance to me because in my last year as a sales rep, almost all of my underperforming accounts were supposedly due to the business owners or their family members being in the hospital.

Among the other more common words likely to be mentioned by defaulters is hospital. This word holds special significance to me because in my last year as a sales rep, almost all of my underperforming accounts were supposedly due to the business owners or their family members being in the hospital.

And it wasn’t just me. It seemed like every deal that was going bad in the office involved the hospital. Any time one of us was due to contact an account with an issue, we made bets that a hospital would come up in the story. (Seb, if you’re reading this, apparently it’s not a coincidence.)

I express no opinion regarding whether or not their stories were true, but statistics show that borrowers that mention hospital are more likely to default.

In the study’s Abstract, the professors wrote:

Using a naïve Bayes analysis and the LIWC dictionary of writing styles we find that those who default write about financial hardship and tend to discuss outside sources such as family, god and chance in their loan request, while those who pay in full express high financial literacy in the words they use. Further, we find that writing styles associated with extraversion, agreeableness and deception are correlated with default.

While the study focused on Prosper, their almost identical competitor, Lending Club, may have realized this trend earlier. In March 2014, Lending Club announced that investors would no longer be able to view the free-form writing portion of the borrower loan application. Citing “privacy reasons,” investors lost a valuable clue into the repayment probability of their notes.

But would it really have helped? The researchers wrote:

Using an ensemble learning algorithm we show that leveraging the textual information in loan requests improves our ability to predict loan default by 4-5.7% over the traditionally used financial information.

Nothing to see here folks, move along and approve

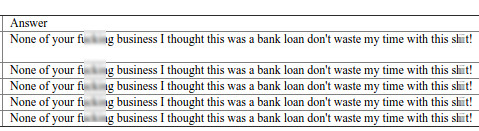

Curiously, Lending Club doesn’t want its investors to have access to a data point with such significant importance. Perhaps it’s because of disasters like this, where one borrower used the free-form writing section to spew profanities. Ironically, the loan was approved and issued anyway.

For tech-based platforms like Lending Club however, they noticed the “story” aspect of a loan had become less relevant because of overwhelming investor demand. Investors weren’t evaluating the written portion of the loan application as much anymore. According to their blog post at the time of the announcement, “Fewer than 3% of investors currently ask questions and only 13% of posted loans have answers provided by borrowers. Furthermore, loans are currently funding in as little as a few hours – well before borrower answers and descriptions can be reviewed and posted.”

It had become all algorithms and APIs where loans were fully funded by investors before the written portions could even be published on the website. Had anyone actually taken the time to read the above loan application answers, they probably wouldn’t have allocated money towards it.

But while removing the storyline from the data might give investors fewer methods to detect a good loan, it could actually protect them from getting drawn into a bad loan.

One of the authors of the above referenced study, Professor Michal Herzenstein of University of Delaware, found in 2011 that borrowers could manipulate lenders into not only approving them, but giving them more favorable terms.

You can trust me 😉

In a story that appeared on UD’s website in 2011, titled Good Storytelling May Trump Bad Credit, Herzenstein’s research discovered that borrowers who constructed a trustworthy picture of themselves “could lower their costs by almost 30 percent and saved about $375 in interest charges by using a trustworthy identity.”

The study referred to six possible categories or identities that borrowers would try to impress upon lenders to describe themselves (trustworthy, successful, economic hardship, hardworking, moral, religious). The story explains:

The more identities the borrowers constructed, the more likely lenders were to fund the loan and reduce the interest rate but the less likely the borrowers were to repay the loan – 29 percent of borrowers with four identities defaulted, where 24 percent with two identities and 12 percent with no identities defaulted.

It’s a case of measurable borrower manipulation.

“By analyzing the accounts borrowers give and the identities they construct, we can predict whether borrowers will pay back the loan above and beyond more objective factors like their credit history,” said Herzenstein. “In a sense, our results offer a method of assessing borrowers in ways that hark back to the earlier days of community banking when lenders knew their customers.”

Today’s tech-based lenders that are dead set on removing this human aspect from the equation may be taking a shortsighted approach after all as they evidently still struggle to make predictions with their numbers-only approach.

For example, a poster on the Lend Academy forum recently wrote this to me about early defaults in today’s algorithmic environment, “It would be nice if LC could predict who is going to default in the first few months of the loan and deny them, but I don’t think that is entirely possible.”

It reminded me of a big merchant cash advance deal I approved years back that passed all of the qualifying criteria with flying colors and still defaulted on the very first day. The merchant’s response to why he defaulted on day one? He felt like screwing us over… “Come sue me,” he said.

In a later meeting to review the deal’s paperwork, a group of managers agreed that I had done all I could to make the approval decision except one. I failed to account for the asshole factor.

Far from satire, it is not uncommon for financial companies to refer to an asshole factor in some regard. It’s a very subjective variable but it can make all the difference between an applicant that’s going to pay and one that’s not. Suddenly none of the hard data matters.

Is the applicant an asshole?

In a recent blog post by loan broker Ami Kassar, titled The Single Most Important Rule in Our Company, Kassar wrote, “if a customer, employee, or partner acts like a jerk – we don’t want to do business with them. If you want to be less diplomatic, you can call the rule – the no ###hole rule.”

In a recent blog post by loan broker Ami Kassar, titled The Single Most Important Rule in Our Company, Kassar wrote, “if a customer, employee, or partner acts like a jerk – we don’t want to do business with them. If you want to be less diplomatic, you can call the rule – the no ###hole rule.”

In many circumstances, the measure of someone being an asshole is relative to another person’s perception. There’s even an entire book on that subject if you’re interested. But what’s trickier, is that according to some studies, being an asshole is a positive thing in business. Would that also make them better borrowers statistically?

Referring back to the original cited study, one has to wonder if there might potentially be a list of words that more closely correlate with being an asshole. I don’t think anyone’s ever examined the Prosper data for that before.

You might not be able to quantify asshole-ishness from the text, but something as basic as a person’s pronouns can speak volumes about their personality or intentions. According to Professor James Pennebaker in the Harvard Business Review:

A person who’s lying tends to use “we” more or use sentences without a first-person pronoun at all. Instead of saying “I didn’t take your book,” a liar might say “That’s not the kind of thing that anyone with integrity would do.” People who are honest use exclusive words like “but” and “without” and negations such as “no,” “none,” and “never” much more frequently.

But saying “I” over “we” doesn’t necessarily make you less of a liar. Pennebaker discovered that depressed people use the word “I” much more often than emotionally stable people.

Being emotionally stable would probably make for a better borrower than a depressed one, but with all these influential and conflicting language clues, how can an underwriter possibly make the right choice?

For instance, if the following line appeared on the free-form writing portion of an application, how should it be interpreted?

Using all of the mentioned research as a guide, I’m inclined to consider the applicant a: trustworthy depressed lying asshole that’s not going to pay.

I = Depressed

We = Liar

God = 2.2x more likely to default

Have always been able to pay back = trustworthy

Hurry up and fund me = asshole

We could easily get caught up in the language here and ignore the obvious positives about this hypothetical applicant, such that they have an 800 FICO score and a solid six figure income. Shouldn’t that weigh more heavily? It’s easy to get distracted.

Perhaps Lending Club’s removal of the free-form writing section was for the investors’ own good. Even the borrower that repeatedly wrote, “None of your f**king business I thought this was a bank loan don’t waste my time with this sh**t!” is still current on all their payments after two and a half years.

To brokers like Kassar, the asshole factor is not so much about the likelihood of default anyway, but peace of mind. “Why invest emotional energy in putting up with shenanigan’s when there are so many good people who need our help,” he wrote.

Word is bond?

Regardless of what one study revealed about applicants that invoked God said about the likelihood of default, declining applicants on the basis of writing or talking about God could certainly be argued as religious discrimination. In many instances, religion is a protected class. Sometimes you have to ignore correlations because they can be deemed discriminatory.

One thing is for sure though, back in 2006 the upstanding characters I had created in my mind about the religious book store owners were upended when they disappeared into the night with all the money. Their words got in my head and I approved them perhaps because of it.

Years later, an asshole defaulted on the first day and not long after that, there would be a mysterious spate of accounts whose poor performance would be attributed to supposed hospital related events.

What’s buried in a person’s words? The answers allegedly. I promise…

When the Money’s Gone in Peer-to-Peer, It’s Gone

June 4, 2015 If you held on to stock index funds throughout the financial crisis, you eventually made all your money back and then some. A beautiful characteristic of the stock market is that being down doesn’t erase the money lost permanently. The value can always go right back up.

If you held on to stock index funds throughout the financial crisis, you eventually made all your money back and then some. A beautiful characteristic of the stock market is that being down doesn’t erase the money lost permanently. The value can always go right back up.

With peer-to-peer member payment dependent notes, like the kind Lending Club and Prosper sell to investors, there is no comparable way to recover losses. Once a loan defaults, that money is gone. Optimism, a market rally, and good consumer news won’t bring it back.

Anil Gupta, the co-founder of PeerCube summed this up well in the Lend Academy forum:

With losses in P2P lending, the challenge is you never recover “double digit percentage” losses incurred. There is finite life for a loan and once it is charged off, you not only have lost your principal but also any possibility of future returns from the sunk money in the loan. With stock, at least you don’t realize losses until you are ready to realize them or company goes bankrupt or you can wait out for stock to recover or double-down. Troubled P2P notes are like stock options that expire worthless.

The potential to lose money permanently with no chance to recover simply by waiting it out should weigh heavily on your decision to invest in P2P notes.

Small Business Lending is King to Institutional Investors

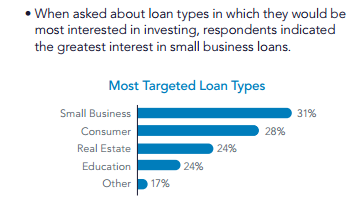

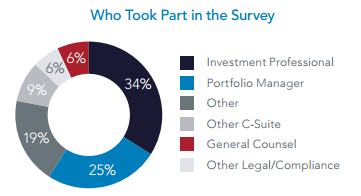

June 2, 2015Richards Kibbe & Orbe LLP and Wharton FinTech polled more than 300 institutional investors to gauge their thoughts on marketplace lending. They published their findings in a recently released report.

The surveyors seemed surprised that institutional investors indicated their interest in small business loans was greater than that of consumer, real estate, education, and everything else.

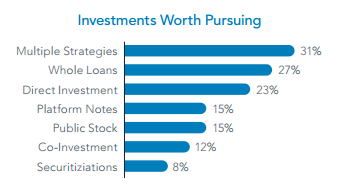

Securitizations ranked lowest on the list of investments worth pursuing and buying whole loans was second only to “multiple strategies.”

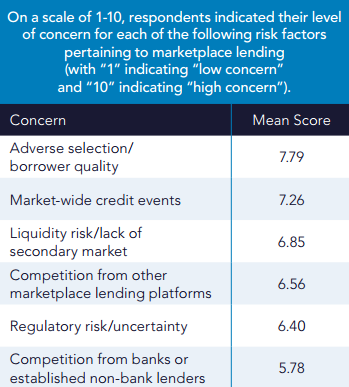

Regulatory risk and uncertainty was low on the list of concerns while borrower quality was the most concerning factor. Curiously, competition was the least concerning of all.

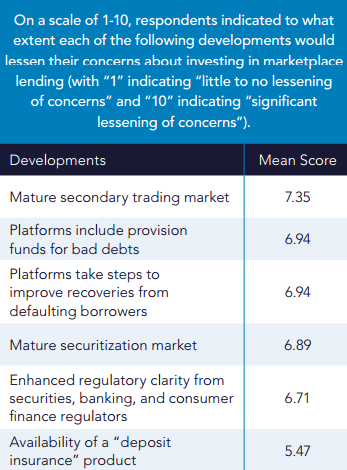

Speaking to the liquidity issues of the assets, institutional investors indicated that the development of a mature secondary trading market was more likely than anything else to lessen their concerns about marketplace lending.

Do any of these results surprise you?

Download the Key Findings report

Why We Shouldn’t Stop Calling it Peer-to-Peer Lending

June 1, 2015 There’s a troubling undercurrent brewing in the marketplace industry, the death of the word peers. We’re not supposed to say peer-to-peer lending anymore since few platforms actually allow for people to lend directly to their peers. In the case of Lending Club and Prosper, investors are actually lending money to the platforms themselves.

There’s a troubling undercurrent brewing in the marketplace industry, the death of the word peers. We’re not supposed to say peer-to-peer lending anymore since few platforms actually allow for people to lend directly to their peers. In the case of Lending Club and Prosper, investors are actually lending money to the platforms themselves.

Emphasizing the appropriate terminology probably makes it easier for people to understand. If it’s not peer-to-peer after all, then calling it that only serves to mislead potential borrowers and investors alike. And yet the term persists largely because the average person is still able to invest in an asset class it never was able to before, notes backed by the performance of individual consumer loans.

It could be argued that without money from peers to buy these notes, the loans themselves would never get issued, making it still peer-dependent or at least peer-relevant.

A game for Wall Street

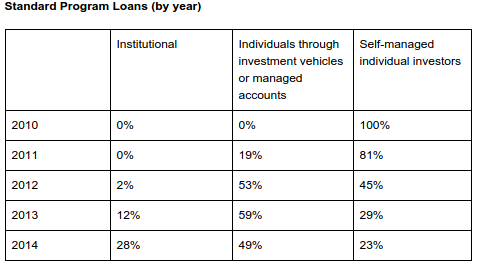

Jorge Newberry wrote several months ago that the little guy as most of us imagine a peer to be, is dead. He was replaced by Wall Street, BlackRock, and Wealthy bankers. “These were killers,” He wrote. He added that while the industry “initially attracted ordinary citizens to invest in modestly sized consumer loans to people like them, over the last few years those peer investors often have been elbowed out and replaced by Wall Street’s finest.”

Retail investors have bemoaned the trend via online message boards, sometimes even accusing the platforms of giving the institutions first dibs on the highest quality loans and leaving the little guys to fight over nothing but the scraps that are more likely to underperform.

Even Dara Albright, the co-founder of the LendIt conference has acknowledged the takeover. In The Financial Advisor’s Guide to P2P Investing, Albright writes, “Unfortunately, what began as a true person-to-person marketplace – with the ordinary individuals lending to and borrowing from one another – has since become monopolized by institutional investors whose deep pockets and technological advantages have all but driven the individual lenders out.”

Further along in the paper, Albright makes the case that individuals need to take advantage of the yield these loans offer to narrow the wealth divide. She makes a compelling argument for investing but stops short of proposing a solution to regain market share. “There aren’t enough p2p loans to facilitate the strong investment appetite,” she concluded.

But just as the marketplace community has conceded the death of peers, the numbers don’t exactly reflect their sentiment.

Only 28% of Lending Club’s loans went to institutional investors in 2014.

Only 28% of Lending Club’s loans went to institutional investors in 2014.While Newberry and Albright have made the case that retail investors are being locked out, there’s a dangerous flip side, they just might be getting locked in. If marketplace lending truly is becoming a game for Wall Street by Wall Street, then the few retail investors who are invested in it could eventually become collateral damage in a pissing match between wealthy bankers.

Investor faith

There are already concerns that the incentive for marketplaces are not aligned with those of their investors. PeerCube co-founder Anil Gupta wrote this on the LendAcademy forum about Prosper, “The quest to increase originations and revenue will trump any such risk management attempts, like what happened with banks issuing mortgages to unqualified borrowers in order to boost their own bottom lines.” He wrote that in response to an upset user whose borrower declared bankruptcy before making even a single payment towards their Prosper loan.

The user was questioning how Prosper would handle this since the timing of the loan prior to the bankruptcy filing had all the hallmarks of fraud.

Gupta added, “There is very little incentive for LC and Prosper to pursue such collections and recoveries claims. When LC was investing its own money in loans, they pursued collections and recoveries more vigorously (11.19% collection in 2007 vs 5.53% collection in 2011). It is no longer Prosper and LC money at risk.”

The user is not alone in his collections fears. Just a few days earlier I realized that 4.6% of all the notes I had purchased on Lending Club had already defaulted, a number that troubled me considering my average note is only 10 months old. With another 3-4 years still to go until maturity, the rate of defaults is already quite high.

The user is not alone in his collections fears. Just a few days earlier I realized that 4.6% of all the notes I had purchased on Lending Club had already defaulted, a number that troubled me considering my average note is only 10 months old. With another 3-4 years still to go until maturity, the rate of defaults is already quite high.

And while I’ve been told that my own personal stats are relatively normal, other retail investors occasionally run into quirks that force them to question the soundness of the reporting they receive.

For example, veteran users commonly rely on the FICO score updates Lending Club will publish for each issued loan. If a borrower’s score is dropping, you could sell the note for a discount to an interested buyer on a marketplace such as folio. Several people have admitted to using this strategy to mitigate losses. There’s just one problem, a user discovered a discrepancy in Lending Club’s FICO reporting. In at least one case, the borrower’s FICO score may have been overstated by more than a hundred points. For users beholden to the accuracy of these figures in order to properly execute their investment strategy, it’s a difficult pill to swallow.

Call it a kink or an oddity. Maybe it’s something that needs to be fixed or maybe something is being miscommunicated. Whatever is going on there, these are the kinds of risks that institutional capital is supposed to be able to tolerate in their quest for yield, but it’s gut wrenching for retail investors.

In the instance of the suspected bankruptcy fraud, several responses by fellow investors gave the impression that the platform simply isn’t going to care because they make money off of issuing loans, not collecting on them. That’s the exact type of Wall Street attitude that could come back to hurt retail investors.

Marketplace lending might not technically be designed as peer-to-peer but the little guy and their actual peers certainly have their funds at stake. Calling it a game for big banks, the wealthy, and Wall Street only encourages the players involved to take bigger risks, reduce transparency, and shrug off genuine criticism.

We can’t let that happen.

Mapping the Business Financing Industry (Sneak Peek)

May 27, 2015People often ask what the real presence of the merchant cash advance & business lending industry is like in New York City. Below is a map of Midtown Manhattan.

We apologize if we didn’t plot your company on here. Let us know you exist by signing up for our magazine.

In the May/June issue that’s being sent off to the printers at this very moment, we explore the industry scene in lower Manhattan. Midtown may have been a birthing place and permanent home for industry titans, but Wall Street, long believed to be a haven for stock brokers has been overrun by a new kind of broker.

You’ll just have to stay tuned to read more. If you’re not signed up to get our free print magazine, register now.

Also in the May/June issue:

- An examination of a new trend, consolidating loans and advances.

- Watching everyone else get rich off alternative lending? Whether you’re in underwriting, administration, operations, or sales and whether you have a lot of money to invest or just a little, there are opportunities available to “get in”. You might be in this industry but are you in this industry? We’ll run through the basics of what’s available out there. Become a player or just educate yourself.

- And more!

OnDeck Gets Taste of its Own Medicine

May 24, 2015 You know those subtle and not so subtle knocks OnDeck has made about merchant cash advances over the years regarding costs and transparency? Well, the tables have turned.

You know those subtle and not so subtle knocks OnDeck has made about merchant cash advances over the years regarding costs and transparency? Well, the tables have turned.

A supposed unnamed merchant shared their capital raising adventure stories with Fundastic and apparently confused the OnDeck cost factor of 1.24 with an APR of 24%. “The interest rate was 24%, which we thought was excessive, as well as the daily $984 payments we got as part of the deal, but in the end we moved forward with the line,” the business owner reported. A Fundastic editor’s note explained the merchant’s APR was actually around 52% because of the closing fees.

The business owner continued to gripe about not receiving an amortization schedule, as well as the fact that they couldn’t pay off the loan early without incurring a penalty.

Apparently the simplified dollar for dollar cost that OnDeck outlined wasn’t forthcoming enough for them, and they were much more satisfied when they switched to Lending Club.

The merchant then went on to explain that their Lending Club business loan rate was only 9.9%, down from OnDeck’s 24%.

Transparency and full understanding at last?

Ironically, Fundastic had to add yet another note to show that the APR was actually 12.96%. 9.9% was not an APR. “LendingClub had a transparent loan — reasonable interest rate (we have 9.9% + 3% origination for a 2-year loan),” the business owner wrote, yet it seems he was unaware of the APR here either.

Fundastic ultimately concluded, “If you qualify for both LendingClub and OnDeck business loans, I can’t see any reason why you would go with OnDeck. LendingClub’s loans are cheaper in cost [and] more transparent.”

Lending Club might’ve been cheaper in this scenario but the merchant appears to have gotten similar information from both lenders. I’m not sure how much more transparent a lender can be when they spell out exactly how much you have to pay back, though an APR would be useful for certain comparative purposes.

Them’s fightin’ words

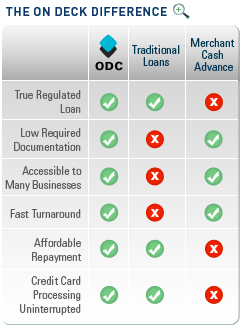

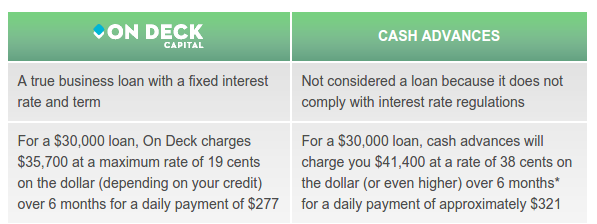

The jab at OnDeck though is reminiscent of the way OnDeck historically attacked merchant cash advances. In a 2008 press release, they wrote, “On Deck Capital fills the void between bank loans and alternative business financing products such as merchant cash advances which, similar to payday loans, charge excessive percentage rates for short term capital.”

The jab at OnDeck though is reminiscent of the way OnDeck historically attacked merchant cash advances. In a 2008 press release, they wrote, “On Deck Capital fills the void between bank loans and alternative business financing products such as merchant cash advances which, similar to payday loans, charge excessive percentage rates for short term capital.”

They even used to display this little chart to explain just how much merchant cash advance sucked compared to them.

Affordable repayment? NOPE!

Meanwhile, OnDeck is still not profitable after 8 years. That either just goes to show how hard it will be for them to compete with Lending Club’s pricing or it indicates that Lending Club is severely underpricing its business loans. It might be the latter.

Lending Club’s business loan program is still highly experimental and dozens of business lenders have entered the space with the belief that undercutting higher priced products right out of the gate will magically yield positive results.

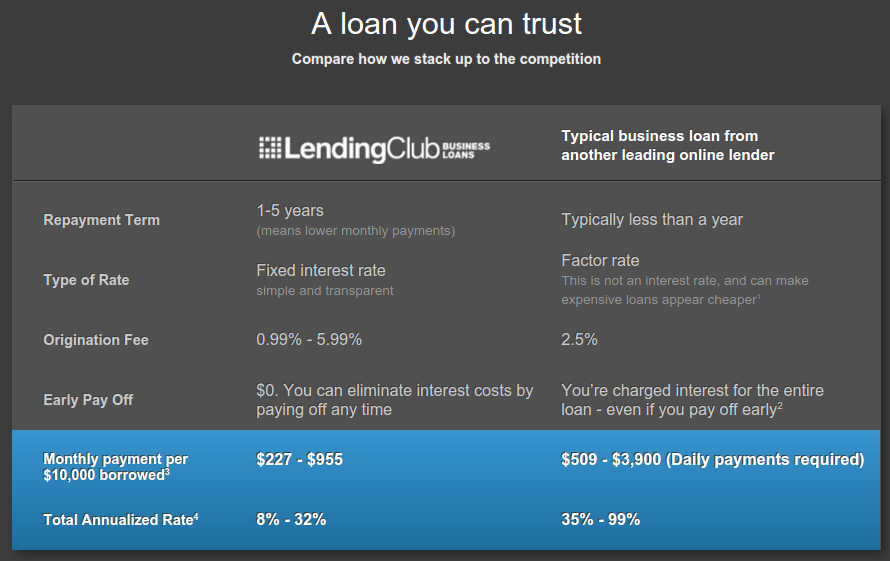

Does this look familiar? OnDeck is being attacked by Lending Club with its own playbook:

And in case you weren’t sure if they were comparing themselves to OnDeck specifically, the 2.5% origination fee is the number that appears right on OnDeck’s website. “We charge an origination fee of 2.5% of the loan amount for your first loan,” it states.

And here’s a snippet of a chart that used to appear on OnDeck’s website:

OnDeck has repeatedly stated that competitive pressure has not been the reason that their interest rates are dropping. It may actually be in anticipation of a brewing public relations war. Lending Club’s supporters are beginning to attack OnDeck in the same way that OnDeck attacked merchant cash advance companies.

Most merchant cash advance companies held firm on their terms over the years and it has paid off. Costs have come down where warranted, but few have been interested to actually underprice their product and risk bankruptcy just to appease criticism.

The circumstances are slightly different for OnDeck who has more to lose as a public company. If their model is dependent entirely on growth and Lending Club begins to snatch some of the lucrative partnerships away from them, their shareholders might suffer in a big way. They can’t have that, so they’re dropping their rates.

Perhaps they should take a page from the merchant cash advance playbook and hold firm, or given their current financials, even raise their rates. Let Lending Club do their thing. Whether the rate is 9.9% or 12.96% is great for a small business, but it’s unlikely to be sustainable or profitable for the lender.

How safe is small business lending really?

Did you know that 29.4% of all Cold Stone Creamerys that received an SBA 7(a) loan defaulted? 29.4% of all Quiznos have defaulted. 26.4% of all Aamco Transmissions have defaulted.

Scarier yet, the SBA’s special ARC loans that were put together in the wake of the recession had an anticipated 60% default rate across the board.

These figures should serve as a warning to any startup business lender, especially if they’re taking jabs at their higher priced competitors.

It’s a great time to get a loan as a merchant, but a politically tough environment for a lender to price that loan profitably. One day you’re the hot new low cost alternative serving up a public relations beating to the standard bearers of alternative finance, the next day someone’s using the exact same strategy on you.

Can OnDeck take the heat?