The Top Small Business Funders By Revenue

September 14, 2017Thanks to the Inc 5000 list on private companies and earnings statements from public companies, we’ve been able to compile rankings of alternative small business financing companies by revenue. Companies that haven’t published their figures are not ranked.

| SMB Funding Company | 2016 Revenue | 2015 Revenue | Notes |

| Square | $1,700,000,000 | $1,267,000,000 | Went public November 2015 |

| OnDeck | $291,300,000 | $254,700,000 | Went public December 2014 |

| Kabbage | $171,800,000 | $97,500,000 | Received $1.25B+ valuation in Aug 2017 |

| Swift Capital | $88,600,000 | $51,400,000 | Acquired by PayPal in Aug 2017 |

| National Funding | $75,700,000 | $59,100,000 | |

| Reliant Funding | $51,900,000 | $11,300,000 | Acquired by PE firm in 2014 |

| Fora Financial | $41,600,000 | $34,000,000 | Acquired by PE firm in October 2015 |

| Forward Financing | $28,300,000 | ||

| IOU Financial | $17,400,000 | $12,000,000 | Went public through reverse merger in 2011 |

| Gibraltar Business Capital | $16,000,000 | ||

| United Capital Source | $8,500,000 | ||

| SnapCap | $7,700,000 | ||

| Lighter Capital | $6,400,000 | $4,400,000 | |

| Fast Capital 360 | $6,300,000 | ||

| US Business Funding | $5,800,000 | ||

| Cashbloom | $5,400,000 | $4,800,000 | |

| Fund&Grow | $4,100,000 | ||

| Priority Funding Solutions | $2,600,000 | ||

| StreetShares | $647,119 | $239,593 |

Companies who were published in the 2016 Inc 5000 list but not the 2017 list:

| Company | 2015 Revenue | Notes |

| CAN Capital | $213,400,000 | Ceased funding operations in December 2016, resumed July 2017 |

| Bizfi | $79,000,000 | Wound down |

| Quick Bridge Funding | $48,900,000 | |

| Capify | $37,900,000 | Wound down |

The Google Battle for Lending and SMB Finance Keywords

September 14, 2017The online lending battle is at least in part being fought online. Below is a chart of organic page 1 rankings in Google for some of the industry’s biggest players, banks, and the SBA. (Hat tip to Fundera and NerdWallet):

| Keywords | OnDeck | Kabbage | Fundera | Lending Club | NerdWallet | National Funding | Traditional Banks | SBA.gov |

| business loan | 1 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 4,7 | 6 | ||

| merchant cash advance | 2 | 3 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| working capital | 9 | 4 | ||||||

| commercial loan | 3 | 2,7 | ||||||

| small business loans | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 | |||

| business line of credit | 3 | 2 | 11 | 1,4 | 6,7,8,9,10 | 5 | ||

| fast business loan | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5,6 | ||||

| business loan with bad credit | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

The Top 10 Google Search Results for Merchant Cash Advance in February 2012 compared to now:

| February 2012 | September 2017 |

| MerchantCashinAdvance.com | Wikipedia |

| Yellowstone Capital | OnDeck |

| Entrust Cash Advance | Fundera |

| Merchants Capital Access | NerdWallet |

| Merchant Resources International | Businessloans.com |

| American Finance Solutions | Bond Street |

| Nations Advance | Capify |

| Bankcard Funding | National Funding |

| Rapid Capital Funding | CNN |

| Paramount Merchant Funding | CAN Capital |

The top result in 2012 is a great example of how much easier it was to game Google’s system back then. After achieving rank #1 for MCA and 300 other related keywords, MerchantCashInAdvance.com, which was just a lead generation site, sold for $75,000 in December 2011. The site was later clobbered by Google Penguin for black hat SEO and banished from visibility.

A major shift has obviously taken place over the last 5 and a half years. Is the search results game rigged to advance Google’s own interests? Three years ago I put forth my theory on that.

One thing that’s different between then and now is that Google now has 4 paid links above the organic search results as opposed to 3 and the paid links blend in more with the organic results. With the organic results pushed further down the page, they’re not as visible as they were five years ago.

Read my previous analyses on the industry’s search war over the years:

December 2015 Google Serves Low Blow to Merchant Cash Advance Seekers

March 2015 Google Culls Online Lenders – Pay or Else?

October 2014 Merchant Cash Advance SEO War Still Raging

August 2014 Six Signs Alternative Lending is Rigged: Do Lending Club and OnDeck have a helping hand?

October 2013 Google Penguin 2.1 takes swing at the MCA industry

August 2013 Your merchant cash advance press release may be hurting you

December 2012 Is Google your only web strategy?

July 2012 The other 93% [of leads]

April 2012 The SEO war continues

February 2012 The SEO War for Merchant Cash Advance: The first story on this topic

ShopKeep Joins the MCA Crowd. Are Loans Next?

September 8, 2017

ShopKeep, an iPad-based cloud-connected technology company designed around POS and payments for small businesses, is expanding into MCAs with the launch of ShopKeep Capital in recent days. With its move into funding ShopKeep joins an area that competitor Square already operates in. But while both companies have unlocked the secret of customer acquisition they are not targeting the same small businesses.

Meanwhile this latest move into MCAs is just a step in what ShopKeep CEO Michael DeSimone describes as an evolution, one that could potentially lead to small business lending sooner than later.

“We had a lot of interest from our customers,” said DeSimone, referring to the nearly 25,000 small businesses that are on ShopKeep’s payment and software platform. ShopKeep Capital extends funding offers to eligible small businesses on the ShopKeep platform, and funding is approved within a couple of days.

Playing Field

ShopKeep is entering a space – MCAs — that is only getting more crowded, with the recent addition of iPayment, for instance. And while ShopKeep and Square operate in a similar market segment, they’re targeting different SMBs.

“Our customers tend to be larger than Square and more complex in their business models,” said DeSimone, pointing to the example of a restaurant with numerous employees and multiple locations. On average, customers on the ShopKeep platform generate sales of $350,000 per year.

As a payments company, ShopKeep’s customer acquisition strategy is tied directly to its software and payments businesses.

“This leverages our ability to understand the small business data flowing through our POS platform and manage it the way we do payments based on the premise of greater visibility into their business by the virtue of our payments platform,” said DeSimone.

He is quick to point out that ShopKeep is built on technology, and he said like every other part of the economy tech is disintermediating some parties and bringing others closer to the outcome they desire.

“The closer you are to the actual customer, the more your opportunity is to be able to be top of mind when they need something,” he said. “They have huge amounts of interaction with us. This level of interaction predicated on technology is really what creates the ability to have a relationship with the merchant to then be able to offer them a range of different products and services.”

DeSimone describes ShopKeep more as a technology play than a funder.

DeSimone describes ShopKeep more as a technology play than a funder.

“We have a lot of information most other providers of capital aren’t going to have unless they ask merchants to do a lot of work,” said DeSimone, pointing to an underwriting model that is almost 100% automated.

“We’ve built it to be largely pre-underwritten We only offer advances based on running the merchant through our underwriting model to see who comes up as a good candidate for ShopKeep Capital and making it available to them. We continually tweak the algorithm to make sure we are not being too tight or too loose,” he added.

Funding is the third revenue stream for ShopKeep, with software and payments representing the other two legs of the revenue stool. Meanwhile ShopKeep Capital is turning to its balance sheet to fund MCAs, but that is not the long-term plan.

“Currently it’s coming off our balance sheet, but it won’t be for very long. We have had several discussions with funding partners. And we expect over time we will migrate to more of a loan product and away from MCAs. We will explore the features and benefits of both to understand both our perspective and that of our customers,” said DeSimone, adding that there could be more clarity about the direction of this evolution in the next six months.

If ShopKeep does move into loans, the company could open up the platform to investors. “They are debt funds looking for returns and specific underwriting criteria. They will buy an advance or a loan eventually from what we originate. That’s the model we think we’ll go toward,” he said.

Something DeSimone and other lenders might want to keep in mind is a credit gap that exists among small businesses today, as described by Karen Mills, a senior fellow at Harvard Business School and former administrator of the U.S. SBA.

“There is no doubt that online lenders have identified an important segment that is not getting enough access to credit, but data also shows that borrowers are less satisfied with the interest rates and repayment terms from online lenders than from traditional banks. So even if small businesses are getting the loan, if it is not at an appropriate price, we should still consider this a credit gap,” Mills said.

Future Plans

While loans could be the next growth phase for ShopKeep Capital, this could be one of many new directions that the payments company takes. For instance, with key competitor Square, which boasts a market cap of approximately $10 billion, in pursuit of obtaining a bank charter, they could have company someday.

“It’s an interesting idea. It’s still very early for us but we’re not ruling anything out at this point,” DeSimone said.

For the near term, however, he is focused on ShopKeep Capital, for which he expects to make a couple of key hires for soon. “In my mind, this helps us to be more competitive with Square. I think it’s a really good service for our customers and it fits very well into the other pieces of our business,” said DeSimone.

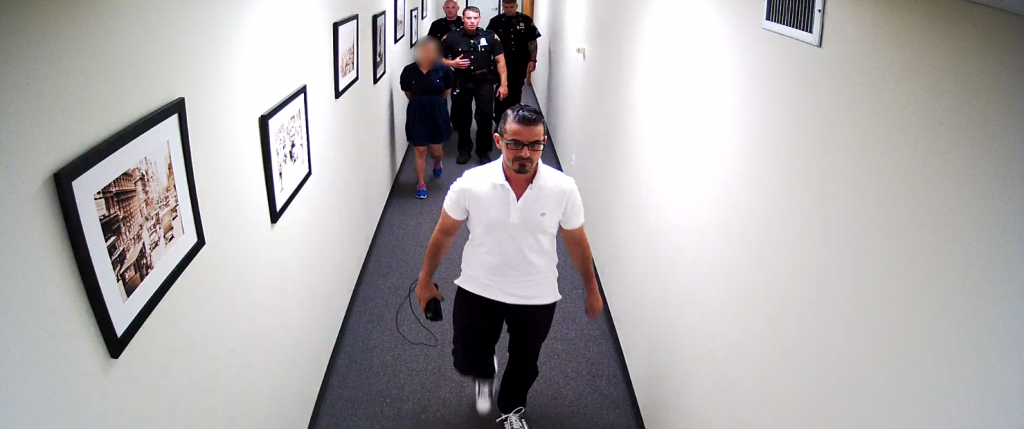

You’re Under Arrest: Funder Takes Extreme Measures to Counter Data Theft

September 4, 2017

An employee of Yellowstone Capital was arrested last month, according to a source who witnessed the events. At the company’s behest, local police entered Yellowstone’s Jersey City office and handcuffed a female employee who was believed to be engaged in the theft and misappropriation of financial data.

A spokesperson for Yellowstone would not comment on the events nor release the name of the accused. deBanked nevertheless obtained a photo of the individual being escorted out by police. We’ve blurred out her face to protect her identity. Several of those present, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said that she had been employed by the company for several years.

When asked more generally about the risks of data leakage in the industry, Yellowstone Capital CEO Isaac Stern said that his company is operating on the edge of hyper vigilance. “Yellowstone is investing tons of time, money, and effort to prevent data theft,” Stern said. “We are doing everything in our power, everything, to address it, and we have even enlisted the assistance of an outside security firm.”

The incident does not stand alone. Last year, a man on Long Island pled guilty to attempted criminal possession of computer related material after being implicated in a merchant cash advance backdooring scheme.

Backdooring is industry jargon for when a broker submits a potential deal to a funder and that file ultimately leaks out to third parties whom the broker did not authorize to handle the information. Often times brokers will point their fingers at the funder for mismanaging data they suspect is escaping out the back door. Such accusations can be detrimental to a funder’s reputation not only with the broker community but also with customers they advance funds to. That’s why some funders are taking data security to new levels.

Greenbox Capital, for example, a funder in Miami, FL told deBanked back in March that their company designed proprietary software to monitor the actions of all users on their system, which allows them to know who clicked on what when, and for how long. They also developed algorithms to detect suspicious behavior and their security team receives an alert whenever it gets triggered. Greenbox had initially conducted a 90-day probe and discovered that two employees were stealing data. They don’t want that to ever repeat itself.

Using a cell phone to take pictures of confidential data may not help rogue employees evade detection, according to several funders who have said there are methodologies to spot this behavior but declined to explain what they are. And the risk of getting caught may not merely be termination, as evidenced by arrests that have taken place thus far. These funders say there have been other arrests over the last few years but that the companies did not want to draw attention to them.

Indeed, of the two backdooring-related arrests deBanked has reported on now, neither would officially confirm them.

“We take ISO information extremely serious,” Yellowstone’s Stern explained, lamenting that the value of deal data can inevitably foster rogue behavior, which they are constantly monitoring for.

Put another way, the personal information of a single performing client could be worth as much as $10,000 or more if it gets into the wrong hands. That’s because it could be used to offer that client a loan, advance or other service. The profit could come in the form of a commission, interest, RTR, a closing fee, or even something more nefarious like stealing their identity.

“We know about the pressure people face to illegally transmit data,” Stern said. “They think we don’t know, but we know the industry. Ultimately we will catch you.”

The State of The Industry (In Memes)

September 2, 2017The state of things in MCA, online lending, and fintech through the disloyal boyfriend meme:

SEE MANY MORE DEBANKED MEMES

The History of Alternative Finance (As Told Through Memes)

Ready to Trade ONDK and LC? Scroll to the bottom of the page

10 Clues You’re Hardcore About Merchant Cash Advance

deBanked Golf Outing 2017 Photos

August 29, 2017Thanks to Marine Park Golf Course in Brooklyn, NY for having us! And thanks to all who came and sponsored!

Ford, MCA Funders Take Pages from Tech-Based Underwriting

August 29, 2017 Alternative lending fever has spilled over into the auto sector, evidenced by the financing arm of automaker Ford’s decision to move beyond FICO and deeper into machine learning for credit decisions. Ford is moving toward alternative lending strategies in an attempt to capture a wider swath of borrowers, including those with “limited credit histories,” and bolster auto sales.

Alternative lending fever has spilled over into the auto sector, evidenced by the financing arm of automaker Ford’s decision to move beyond FICO and deeper into machine learning for credit decisions. Ford is moving toward alternative lending strategies in an attempt to capture a wider swath of borrowers, including those with “limited credit histories,” and bolster auto sales.

Ford’s decision comes on the heels of a study with fintech play ZestFinance, the results of which favor a machine-learning based approach to credit decisions.

Ford’s decision comes on the heels of a study between Ford Credit and fintech play ZestFinance, the results of which favor a machine-learning based approach to credit decisions.

“There is absolutely no change in Ford Credit’s risk appetite. Ford Credit is maintaining the consistent and prudent standards it has applied for years. This enhanced ability to look at data will help us more appropriately place applicants along the full spectrum of the risk scale. The result will be some that some people may appear on that scale who did not before, and some applications that are approved today might not be approved in the future. The risk appetite remains the same,” Ford Credit spokesperson Margaret Mellott told deBanked.

Until now, there has been no aspect of machine learning in Ford Credit’s underwriting process.

“The study showed improved predictive power, which holds promise for more approvals … and even stronger business performance, including lower credit losses,” according to Joy Falotico, Ford Credit chairman and CEO, in a press release.

Ford is targeting consumers with a lack of credit history, especially the millennial generation.

Tech-Driven Underwriting

While Ford embraces tech-driven underwriting, this style is already knit into the fabric of the MCA and online lending communities.

To name a few, Upstart takes a machine learning approach. FundKite developed algorithmic-based underwriting. UpLyft’s underwriting process has an automated component to it.

Alex Shvarts, CTO and director of business development at FundKite, a balance-sheet based funder, said the company has been writing algorithms since the early days. Now the tech- and algorithm-driven funder wants to expand into small business lending in Q1 2018.

Alex Shvarts, CTO and director of business development at FundKite, a balance-sheet based funder, said the company has been writing algorithms since the early days. Now the tech- and algorithm-driven funder wants to expand into small business lending in Q1 2018.

“We’re building our technology to the point that by Q1 next year, we will get into automated loan products. Our technology will be able to underwrite loan products within seconds. We have a lot of data we put together, which allows us to price deals and make offers relatively quickly,” he said.

By a lot of data, Shvarts is referring to hundreds of data points that are used to measure merchant performance. FundKite, which has a default rate of far less than 10 percent, takes the data, reworks and combines it, leading to a fast result.

“Besides the data points we look at the merchant from a collections point of view. If this person or business runs into trouble, could they go out of business or would they be okay?” he said.

That’s where the human element to the underwriting process comes in.

Human Element

While FundKite relies on algorithm-driven underwriting, the funder is not running an online app yet. There is still a need for human participation surrounding data input, information that is then verified by machines.

“The human element is entering the information correctly, and the machine spits out predetermined pricing based on the business data points and industry,” said Shvarts, adding that FundKite views that information in the context of micro-trends in the industry as well as the overall market environment.

“We know that during certain seasons some merchants perform worse than others. The numbers say the merchant should get this, but we dig a little deeper and say no, this merchant can’t handle this much of an advance and repayment along those lines. The final touches are done by humans. Our technology is advanced so that we are able to get to that point a lot faster and more accurately,” Shvarts said.

Second Opinion

Michael Massa, CEO and founder of Uplyft Capital, points to a hybrid approach in the company’s credit underwriting, referring to the automated scoring portion of Uplyft’s underwriting model as a second opinion. “We believe there must be a hybrid of human and automated technology,” said Massa.

Uplyft relies on a proprietary scoring model. The model includes an automated function that attaches a unique rating to the small business based on certain features in the prospective borrower’s profile, such as a home-based versus business location and the number of years the company has been in business, to name a couple.

“It’s only as second opinion for our underwriters, really,” he said, adding that cash flow and affordability are major drivers of the credit decision. “In most cases we price at max affordability for the client while protecting them from overleveraging their accounts, allowing us to provide real help and establish merchant loyalty.”

Second opinion or not the automated function is part of what makes Uplyft a fintech play, setting the funder apart from the banks. “They’re like the payphone and we’re the iPhone. They’re yellow cab and we’re Uber,” said Massa, adding better yet, “we’re Lyft.”

Second opinion or not the automated function is part of what makes Uplyft a fintech play, setting the funder apart from the banks. “They’re like the payphone and we’re the iPhone. They’re yellow cab and we’re Uber,” said Massa, adding better yet, “we’re Lyft.”

Uplyft is in the process of developing a trio of portals designed for merchants, sales partners and investors to be released shortly. “We are API-ing that now into our CRM,” said Massa.

Merchants can access the portal to apply for funding while sales partners use it to submit files and view a status. Investors can track their participation via the portal. The new portals will be available on the website and through a mobile app that Uplyft is in the final stages of developing.

Uplyft also recently inked an exclusive partnership with an undisclosed software company allowing merchants to link their bank account to the application, capturing six months of actual PDF bank statements in the process.

“It can help us with the initial credit decision and when we’re conducting final verifications. We get the actual bank statement. It’s a legitimate bank statement, not a rendition,” said Massa.

Fintech & Auto Finance

As for the auto industry, don’t be surprised to hear about further collaboration between the automakers and the fintech market. “Financial technology is key … as fintech can contribute to an even more seamless and better personalized vehicle financing experience for the consumer,” according to the Ford press release.

Why BFS Capital’s Glazer Is Passing the Torch

August 22, 2017

Marc Glazer co-founded BFS Capital in the early 2000s and has remained at the helm all this time – until now. Glazer has passed the torch over to Michael Marrache, effective last week. He isn’t going too far, as the former chief executive will remain chairman of the board working alongside Marrache on the next chapter for the MCA and small business lending company. Meanwhile the executive pair points to a future not only where there is sustainability but where there is growth.

“We’ve obviously grown the company year after year over the last 15 years, and as with every other type of business and industry there were ebbs and flows. Over the last couple of years with a significant amount of challenges going on, we as a company decided we want to continue to grow but we want to grow in a way that benefits the company from a profitability standpoint as well as serves our customers,” said Glazer.

In April 2017, BFS Capital surpassed $1.5 billion in financings since inception. The company expects to fund more than $300 million in new financings in this calendar year.

“We’ll increase our reliance on algorithmic solutions, transparency in the ISO and customer experience and we will increase the number of financing solutions. Culture is significant for us and we will continue to build on the legacy Marc created,” said Marrache.

Marrache takes the reigns at a time when the industry is at a crossroads that will leave some alt lenders in the dust while other rise to the occasion.

“The stories that were challenging in 2016 look good in 2017,” said Marrache, pointing to OnDeck’s forthcoming profitability, Kabbage’s lofty valuation, CAN Capital’s return to funding, PayPal’s acquisition of Swift Financial and Prosper looking good.

“We think alternative and non-bank lending are in a good place. And yes, some of the folks that are no longer operating in this space were overextended or may have exhibited irrational behavior for pricing or customer acquisition costs. We think what we’re witnessing is the normal lifecycle of the industry. There were lots of participants earlier. Now to participate the industry must show a bit more control and sophistication. If you execute well, the tomorrows will be better than 2016,” said Marrache.

And according to Glazer, because of the changes in the business environment over the last couple of years, it’s going to require a different skillset to take BFS Capital to the next level.

“There are clear differences between starting a company, growing a company and becoming a billion-dollar small business financing platform. We’ve needed to evolve at each stage and now again with Michael’s leadership,” he said.

For Glazer, Marrache was almost always the succession plan.

“To be fair, hiring Michael four years ago, maybe succession planning was in the back of my mind somewhat. But as our relationship developed and as he was COO for three-plus years and then president, it became apparent that Michael’s skill set, passion, desire and how he looked at culture were all similar to myself. Let’s grow, but let’s watch our numbers. Make sure we treat people fairly. And for the businesses we are financing — provide thoughtful capital to help them versus creating problems for them,” said Glazer.

More Funding

BFS Capital’s business model is comprised both of MCAs and small business loans. Alternative funding company CAN Capital does both MCAs and loans and had to pause lending until recently. For BFS, however, it’s all systems go. And that means unequivocally continuing to fund small businesses.

“Absolutely, yes. And there’s no quizzicality in mind. I would say we are going to continue funding small businesses and fund more of them this year than we did last year. And we will fund even more the year after. So absolutely,” Marrache said.

BFS Capital sells through both ISOs and directly to merchants, the former of which is where most originations derive. “There are a number of solutions we are putting together to benefit that network,” said Marrache, adding he doesn’t believe algorithmic solutions will replace underwriters.

“We have a strong legacy of customer underwriting. We believe lower level transactions can be significantly more automated. Above a certain level and certain amounts of origination, we think algorithms and data solutions at that point are a facilitator, not a replacement of our underwriting,” Marrache said.

The Legacy

There was a time when BFS Capital’s growth plans included debuting in the public markets. Those plans have since been sidelined amid a chilly investor reception for alternative lender stocks.

“We spent a lot of effort in our filing,” said Glazer. “But at the end of the day, the market for the space had softened. Going forward I think it’s really going to be a question of what the markets look like and what makes sense for our company. We will evaluate that as the situation warrants.”

IPO or not, it appears Glazer’s legacy is still being written.

“I co-founded the company 15-plus years ago. Before finance and accounting, at heart, I’m an entrepreneur. That’s what I do, what I enjoy. I love starting companies, having the vision and creating things,” he said.

As chairman of the board and a major stakeholder, Glazer will continue to be active in BFS Capital.