Settling Up: Debt Settlement Companies Paid Yellowstone Capital and Everest Business Funding a Half Million Dollars to End Lawsuit

June 12, 2018 A group of debt settlement companies and ISOs have entered into a settlement they’re unlikely to forget. A lawsuit that accused Corporate Bailout, Protection Legal Group, Mark Mancino, Michael Hamill and others of tortious interference with merchant cash advance contracts has led to a settlement in which the defendants agreed to pay Yellowstone Capital and Everest Business Funding $500,000. They also agreed not to offer any services to Yellowstone or Everest merchants in the future, deBanked has learned.

A group of debt settlement companies and ISOs have entered into a settlement they’re unlikely to forget. A lawsuit that accused Corporate Bailout, Protection Legal Group, Mark Mancino, Michael Hamill and others of tortious interference with merchant cash advance contracts has led to a settlement in which the defendants agreed to pay Yellowstone Capital and Everest Business Funding $500,000. They also agreed not to offer any services to Yellowstone or Everest merchants in the future, deBanked has learned.

The original complaint alleged that ISOs had partnered with companies that purport to offer debt relief services to merchants with MCAs. In practice, the complaint said, debt relief was a code word for deceiving merchants to breach their existing agreements so that they could pay fees instead to the debt relief companies.

When asked to comment, Yellowstone Capital CEO Isaac Stern said that there were companies that offer this kind of service the right way but that was not the case here. “The way they’re going about it is really wrong,” he said.

Of note is that the bound parties were not just debt settlement companies but also ISOs and a law firm (Mark D. Guidubaldi & Associates, LLC dba Protection Legal Group).

Additional companies not named in the original complaint but nonetheless bound to the settlement are Mainstream Marketing Group and Corporate Client Services LLC. Websites for both companies say that they offer small business debt relief services.

Coast to Coast Funding LLC, who the defendants represented they had no control of, did not participate in the deal.

The settled matter is not the first of its kind. Everest and Yellowstone have been hammering debt settlement companies with lawsuits this year, according to court records examined by deBanked. In January, Everest sued MCA Helpline and Todd Fisch for tortious interference, and just last month Yellowstone filed a Petition to recover funds that were allegedly fraudulently transferred by Settle My Cash Advance.

In the latter case with Settle My Cash Advance, the defendants are alleged to have actively coached a merchant to hide his money in new bank accounts and hide the paper trail rather than pay the money owed to Yellowstone.

Speaking about no case in particular, Stern said “Imagine getting a commission on a deal [where you help a small business get funding] and then sending it to a debt settlement company. If there are ISOs that are doing that, we’re going to come after you hard.”

New York Institute of Credit Celebrates 100 Years and Honors Harvey Gross

June 12, 2018 About 300 people gathered underneath the soaring ceilings of Guastavino’s ballroom in Manhattan last night to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the New York Institute of Credit (NYIC). Most attendees were members of the association, which provides networking opportunities and education to a myriad of constituents, including factors, financial advisors, lawyers, investors and accountants.

About 300 people gathered underneath the soaring ceilings of Guastavino’s ballroom in Manhattan last night to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the New York Institute of Credit (NYIC). Most attendees were members of the association, which provides networking opportunities and education to a myriad of constituents, including factors, financial advisors, lawyers, investors and accountants.

“[NYIC] is one of the few meeting places that brings judges, investors and professionals together,” said Jack Butler, CEO of Birch Lake, a boutique merchant bank based in Chicago.

In addition to Butler, other members, like Maxwell Cohen, traveled to attend to event. Cohen works in Fort Lauderdale, FL as Managing Partner for Corporate Strategy & Financial Consulting LLC and specializes in underwriting and brokering business loans.

“[NYIC] is great because it connects people in similar sandboxes…and sometimes we can build off each other’s strengths, ” Cohen said. “Everyone here is verified [and] if you’re here, we know you have capabilities to deliver.”

A central part the NYIC centennial celebration was the honoring of the organization’s Executive Director, Harvey Gross, who has worked for organization for 54 years.

A central part the NYIC centennial celebration was the honoring of the organization’s Executive Director, Harvey Gross, who has worked for organization for 54 years.

A montage video of congratulations to Gross included praises from New York judges and others, including:

“He has a way of putting people together that produces spectacular results.”

“He’s been a mentor to so many.”

“Harvey has communicated best practices.”

“Some organizations looks inward. NYIC looks outward, because of Harvey’s leadership.”

“To talk about 54 years in five minutes is not easy, but I will try,” Gross said to the audience upon receiving the award. He explained that when he was 12 years old, his brother suggested that he get into the factoring business. He later told deBanked that he spent the next five or so years learning the business and left school by the time he was 18 to start a career in factoring. When he started working for the NYIC, the organization primarily served the factoring business, and has since expanded.

“I think tonight showed that the NYIC went through a lot of transitions over the last 100 years,” Gross told deBanked. “And we’re excited about new transitions in the next 100 years. And that includes MCA and fintech.”

Second Annual Alternative Finance Bar Association Conference Draws Lawyers from Afar

June 11, 2018 Attorneys who represent alternative finance companies congregated in New York on Friday for the second annual conference of the Alternative Finance Bar Association (AFBA.)

Attorneys who represent alternative finance companies congregated in New York on Friday for the second annual conference of the Alternative Finance Bar Association (AFBA.)

They came for a day of learning about the latest legal developments pertaining to alternative finance, and MCA in particular. Seminars at the conference had names like: “Credit Facilities 101: What an Alternative Finance Company Can Expect,” “Syndication Relationships: Partner? Participant? Investor?” and “Bankruptcy Developments: The Rise of the Adversary Proceeding.”

“I think it’s like heaven for a new attorney in the MCA world,” said Judith Ramos, who is Corporate Counsel at McKenzie Capital in the Miami area.

Another attorney somewhat new to the MCA space and eager to learn more was Alexis Shapiro, General Counsel at Forward Financing in Boston.

“This was one stop shopping to learn about the latest legal developments in the MCA industry,” Shapiro said.

In one seminar, called “Updates on Recent Case Law,” attorney panelists Steven Berkovitch of ABF Servicing and Adam Stein and Christopher Murray of Stein Adler Dabah and Zelkowitz, discussed the positive impact of the Pearl Beta Funding v Champion Auto Sales decision in New York. They spoke about how judges have dismissed lawsuits against their MCA clients by referencing this decision, which establishes that MCA deals are not loans.

Murray reviewed the current climate with regard to MCA cases in New York, California, Texas and Utah. And one panelist emphasized the importance of simply being knowledgeable about the industry by relating a story of an MCA defense lawyer who, when asked by a judge about the interest rate on a particular MCA deal, fumbled and gave a percentage. (MCA deals do not have interest rates given that payments are subject to change over time).

Later, Gregory Nowak, a partner at Pepper Hamilton, entertained the crowd with a few jokes before diving into the details and the risks of syndication. The conference was held at New York offices of Pepper Hamilton, with expansive views of the Hudson River.

Later, Gregory Nowak, a partner at Pepper Hamilton, entertained the crowd with a few jokes before diving into the details and the risks of syndication. The conference was held at New York offices of Pepper Hamilton, with expansive views of the Hudson River.

“We are energized by the response of so many attorneys from different backgrounds in this emerging and evolving industry,” said one of founders of the AFBA, Lindsey Rohan, General Counsel at Platinum Rapid Funding Group in Long Island.

AFBA’s other founders are Kate Fisher, partner at Hudson Cook outside of Baltimore, Patrick Siegfried, Assistant General Counsel at Rapid Advance in Bethesda, MD, and Murray, attorney at Stein Adler outside of New York City.

Robert Cook, one of Hudson Cook’s founding partners, was at the conference. He told deBanked that he remembered back in 2006 when an investment bank client asked his firm to do due diligence on a merchant cash advance company.

Robert Cook, one of Hudson Cook’s founding partners, was at the conference. He told deBanked that he remembered back in 2006 when an investment bank client asked his firm to do due diligence on a merchant cash advance company.

“We didn’t know what that was,” Cook said. “The client looked around for a law firm that had experience with MCAs. They couldn’t find any. So they came back to us and said, ‘You’re going to have to learn.’”

More than a decade later, MCA is no longer so obscure and the AFBA has at least three more planned events in 2018. The next event will be a cocktail reception on October 24th.

For more information, contact: Tiffany@LRohanlaw.com

deBanked was also a sponsor of the second annual AFBA conference.

An Inside Look at Strategic Funding’s Portfolio

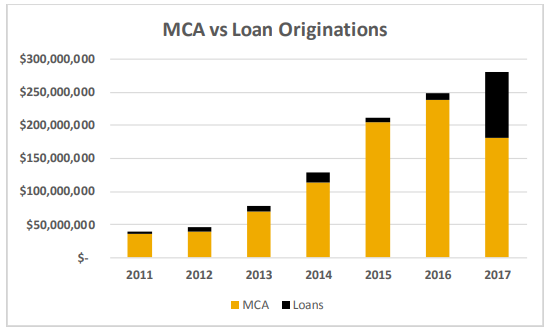

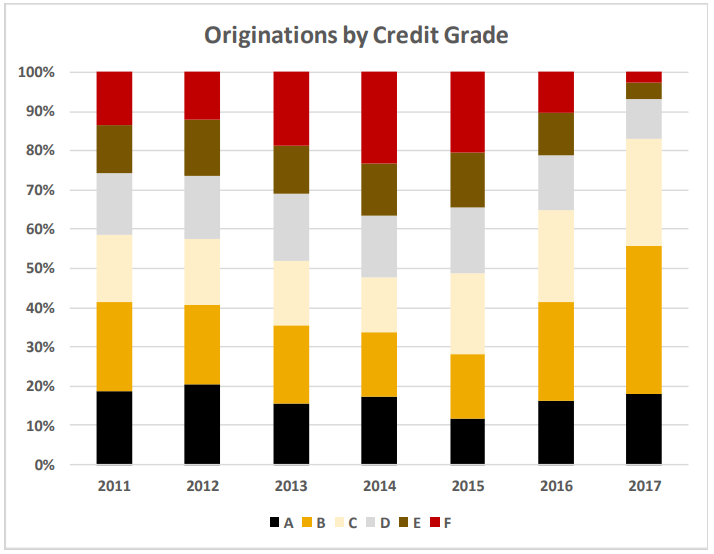

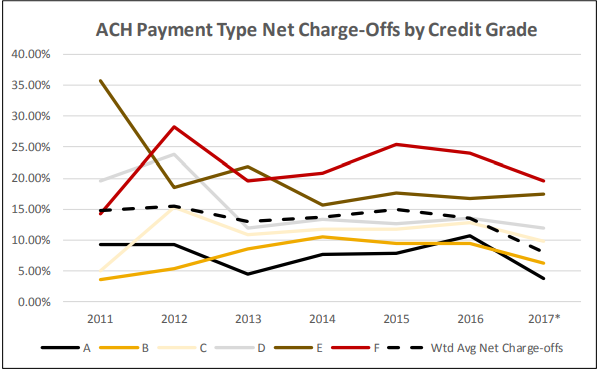

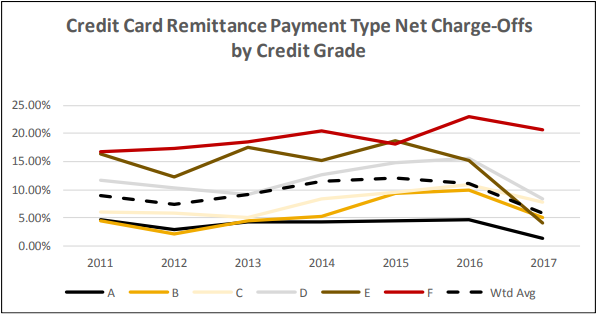

June 10, 2018A Kroll Bond Rating Agency report reveals interesting details about Strategic Funding Source’s $105 million securitization and also their business. Here are a few main takeaways:

Pool breakdown

60% MCA

40% Loans

Average original receivable balance per merchant: $40,705

Weighted Average FICO Score: 649

Weighted Average RTR Multiple: 1.35

Weighted Average Time in Business: 12.5 years

Weighted Average Gross Revenue: $1,729,709

Number of ISOs/referral partners: 1,300

In an earlier interview, Strategic Funding CEO Andrew Reiser said, “It’s certainly exciting to be able to meet the requirements of a securitization. Kroll is a very responsible agency and they put you through a lot of rigor to be able to meet [their] requirements and have a rated bond.”

US Business Funding Will Retain Name & Special Sauce in Wake of Fora Deal

June 8, 2018Fora Financial’s announcement yesterday that it acquired a sizable stake in US Business Funding (USBF) will create one of the “largest, broadest reaching direct sales organizations in the small business alternative lending space,” the company said in a statement.

USBF is a direct sales and marketing company of about 40 to 50 people. Fora Financial founder and CEO told deBanked that his company started working with USBF to obtain leads two years ago and that this acquisition has been in the works for between 12 to 18 months.

Jared Feldman, CEO, Fora Financial

Jared Feldman, CEO, Fora Financial“We were looking for a team that does direct sales and marketing that complements what we do,” Feldman said. “And they’re one of the best at [direct marketing] in the business.”

USBF is based in Santa Ana, CA, and has connected customers to financing since 2008, with an emphasis originally on equipment financing. In 2012, they started facilitating working capital deals and that now makes up 85 percent of the company’s business, according to its CEO Peter Ribeiro.

They provide financing solutions ranging from $10,000 to $10 million. Fora Financial, also established in 2008, is a New York-based funding company that funds MCA deals and provides small business loans up to $500,000.

Consistent with yesterday’s announcement, Feldman said that with Fora Financial and USBF combined, they will likely originate $400 million year. Feldman told deBanked today that, of this amount, about $300 million should come from direct sales.

“We’re more heavily weighted towards direct sales,” Feldman said.

Formerly a company of 100, the new entity will now include about 150 employees and will share resources like capital, technology and access to help with compliance, Feldman said. USBF will retain its name, location and all of its employees.

“We wouldn’t have done this deal unless Peter [USBF founder and CEO] and his team agreed to stay on,” Feldman said. “They have a fantastic brand and we want to avoid getting in their way. We just want to help them to continue doing what they do.”

Feldman said that while USBF will retain its name, “we’re now a combined entity with an east and west coast operation.”

Fora Financial acquired USBF because it did something unique, and Feldman said that Fora is looking for opportunities to acquire other companies that do uniques things in the financing space.

How Gibraltar Capital Advance Became Wellen Capital

June 4, 2018 Gibraltar Capital Advance announced today that it has changed its name to Wellen Capital. The company had been a sister company of Gibraltar Business Capital, but since that company was acquired in March of this year, Gibraltar Capital Advance has operated independently.

Gibraltar Capital Advance announced today that it has changed its name to Wellen Capital. The company had been a sister company of Gibraltar Business Capital, but since that company was acquired in March of this year, Gibraltar Capital Advance has operated independently.

“The Gibraltar name has been well-regarded as a leader in the alternative finance market for many years,” said Jim Teppen, President of what is now known as Wellen Capital. “We entrust it to our former colleagues at Gibraltar Business Capital, knowing they’ll successfully carry the brand’s tradition forward.”

Wellen is no one’s surname at the company, according to Chief Revenue Officer Steve O’Connor.

“One of the things that makes us unique in the capital advance space is that we’re from Chicago,” O’Connor said. “We’re a midwestern company, and the way that we crafted this name had a lot to do with words and phrases and images that were midwestern, even though it’s not obvious.”

O’Connor also noted that Wellen is easy to say and easy to type. In addition to the name change, the company also announced today the WellenScore Application Scoring System, Wellen’s proprietary, data-driven system for evaluating applications.

O’Connor acknowledged that alternative finance companies have been using algorithms to make funding decisions for years, with varying degrees of success.

“Our approach was always to gather enough data first to make sure that we had enough information to inform a data enabled decisioning model,” O’Connor said of Wellen, which was founded in 2012. “And that’s not the kind of thing you can just do overnight.”

The company has been using this system now for more than six months. This doesn’t mean that Wellen now relies exclusively on computers to make funding decisions.

“Our process leverages automation and data-enabled decisions, but isn’t just a ‘black box,’” said Wellen Chief Operating Officer Ed Job. “Good funding decisions are made by working with our sales partners to gather needed data and decide how to best structure a capital solution for our customers.”

Wellen, which provides merchant cash advance exclusively, is based in Chicago and employs 30 people.

Why Small Businesses Sought Financing in 2017, and Why They Were Denied

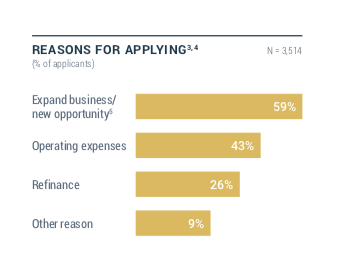

May 24, 2018 Nearly 60 percent of small businesses applied for financing in 2017 because they wanted to expand their business or pursue new opportunities, according to the latest report by the Federal Reserve. Forty-three percent of small businesses sought financing for operating expenses while 26 percent sought capital for refinancing. Nine percent had a different reason.

Nearly 60 percent of small businesses applied for financing in 2017 because they wanted to expand their business or pursue new opportunities, according to the latest report by the Federal Reserve. Forty-three percent of small businesses sought financing for operating expenses while 26 percent sought capital for refinancing. Nine percent had a different reason.

Of course, not all applications are funded. Forty-six percent of small businesses received all the financing they sought, 12 percent received most (more than 50 percent) of it, 20 percent received some (less than 50 percent) of the financing they desired and 23 percent were denied financing altogether.

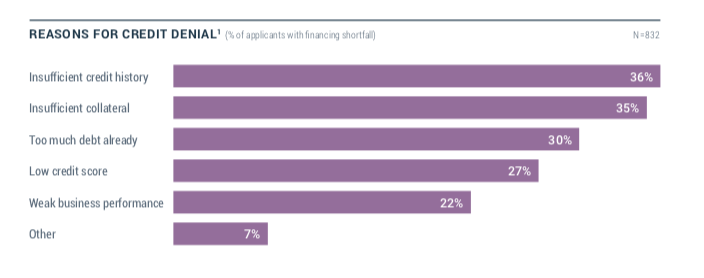

Of the reasons why merchants were denied funding, “Having insufficient credit history” ranked number one, according to the report. A very close second was “Having insufficient collateral,” followed by “Having too much debt already.” After that, in descending order, came “Low credit score,” “Weak business performance” and “Other.”

The “Having insufficient collateral” category does not apply for MCA financing, but the other categories do. According to Nick Gregory, founding partner at Central Diligence Group, which provides MCA underwriting services, “Having too much debt already” is perhaps the main reason why merchants seeking cash advances get declined.

“A lot of times the merchants are overleveraged,” Gregory said.

He explained that if a merchant also has something like two MCA arrangements (or positions) already, that merchant likely has taken on too many contractual obligations which will often be a reason to decline the application. In Gregory’s experience, another common reason for declining an MCA financing application is “Weak business performance.”

Contradictory to the Federal Reserve report’s top reason for denying financing to a small business borrower, Gregory said that “Having insufficient credit history” is seldom a reason to deny MCA financing. This disconnect likely comes from the fact that the report includes all types of small business financing, with MCA accounting for just seven percent. The number maybe seem small, but it continues to increase while small business applications for factoring have decreased.

More Small Businesses Seeking Merchant Cash Advances Than Factoring

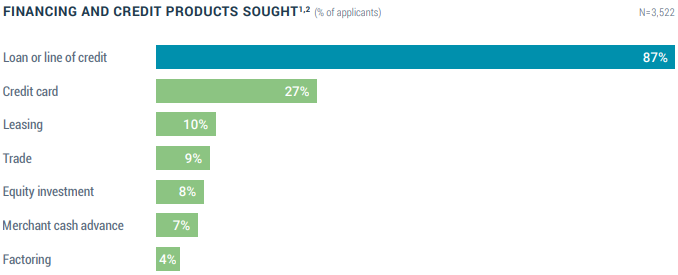

May 23, 2018 Seven percent of small employer firms in the US that applied for financing in 2017 applied for a merchant cash advance, the latest report by the Federal Reserve shows, while only 4% applied for factoring. Small employer owned firms were defined as businesses that have 1 to 499 full-or part-time employees. 69% of those surveyed generated less than $1 million in revenue last year. That revenue demographic may be on the low end for the factoring industry though. Factoring’s popularity in that demographic, however, decreased in 2017, according to the report. The 4% figure of small businesses that applied for factoring in 2017 was down from 7% in 2016.

Seven percent of small employer firms in the US that applied for financing in 2017 applied for a merchant cash advance, the latest report by the Federal Reserve shows, while only 4% applied for factoring. Small employer owned firms were defined as businesses that have 1 to 499 full-or part-time employees. 69% of those surveyed generated less than $1 million in revenue last year. That revenue demographic may be on the low end for the factoring industry though. Factoring’s popularity in that demographic, however, decreased in 2017, according to the report. The 4% figure of small businesses that applied for factoring in 2017 was down from 7% in 2016.

Auto and equipment loans had the highest approval rates among all financing options available to small businesses, at 82%. Merchant cash advances followed behind them at 79%. Lines of credit and business loans carried approval rates of 69% and 62% respectively. SBA loans came in at 54%.

When it comes to satisfaction, online lenders such as Lending Club, OnDeck, CAN Capital, and PayPal, have markedly improved over time, the report shows. The net satisfaction score of online lenders has increased from 19% in 2015 to 35% in 2017.

On transparency, online lenders rank at about the same level as large banks, though applicants were more likely to be dissatisfied with the interest rates of an online lender and the long and difficult application process with a large bank.