“Predatory Lenders” Slammed as Bill to Ban Confessions of Judgment Nationwide Advances

November 14, 2019

(Bloomberg is majority owner of Bloomberg News parent Bloomberg LP)

Rep. Nydia Velázquez (D) celebrated the advancement of a bill on Thursday that aims to outlaw confessions of judgment (COJs) in commercial finance transactions nationwide. HR 3490, dubbed the Small Business Lending Fairness Act, made its way through the House Financial Services Committee on a vote of 31-23. The next step will be a floor vote.

Velázquez made direct references to a Bloomberg News story series published last year about “predatory lending” and a NY Times article about Taxi medallion loans as her basis for supporting it. Velázquez said that New York had become a breeding ground for “con artists” that relied on COJs to prey on mom-and-pop businesses. The congresswoman singled out New York because of recent taxi medallion loan outrage and the state’s alleged reputation as a “clearing house” for obtaining fast easy judgments against debtors nationwide. New York took a major step to change that practice earlier this year through a new law that only allows COJs to be filed in the state against New York residents. HR 3490 seeks to prevent them from being filed in every state, including New York.

Ironically then, the bill is at odds with the new New York law in that Velázquez’s bill, if it became federal law, would go so far as to prevent New York’s own courts from entering a COJ against New York’s own residents, if it resulted from a commercial finance transaction.

Ironically then, the bill is at odds with the new New York law in that Velázquez’s bill, if it became federal law, would go so far as to prevent New York’s own courts from entering a COJ against New York’s own residents, if it resulted from a commercial finance transaction.

While momentum in the House could be perceived as a partisan initiative unlikely to survive the Senate, the bill has in fact garnered a degree of Republican support, recently through Rep. Roger W. Marshall, a co-sponsor of the bill, and originally by Senator Marco Rubio who initially sparked the call to action in the Senate last year.

The Financial Svcs Committee approved my bill to end "Confessions of Judgment", contracts that allow for unfair, predatory small business loans & that have been linked to #taximedallion crisis in NYC.

On to the House floor!

Read More: https://t.co/xHaYnLKme4@NYTW @FSCDems

— Rep. Nydia Velazquez (@NydiaVelazquez) November 14, 2019

A co-author of the COJ-centric Bloomberg News stories was quick to take the credit for the advancement of Velázquez’s bill.

the bill was drafted in response to our series Sign Here to Lose Everythinghttps://t.co/lrfIW3P0yi

— Zeke Faux (@ZekeFaux) November 14, 2019

Selecting a Third-Party Commercial Collection Agency

November 8, 2019 It’s said that anyone can lend money out but the hard part is getting paid back. The latter part is full of nuance, a 32-page white paper authored by Minnesota-based Dedicated Commercial Recovery (Dedicated) reveals.

It’s said that anyone can lend money out but the hard part is getting paid back. The latter part is full of nuance, a 32-page white paper authored by Minnesota-based Dedicated Commercial Recovery (Dedicated) reveals.

“Choosing a third-party commercial collection agency is a matter of comparing potential returns and risks in order to achieve an optimal balance of both,” the report opines. “The purpose of this paper is to present one possible outline for making such a balanced choice.”

While it may be views that Dedicated espouses, the report stops short of self-promotion while raising valuable questions that anybody contracting with a commercial collection agency would benefit from considering. After all, even if third-party collections inherently suggests that relations between the original parties have broken down, the collections experience can set the final tone on how a customer feels about your brand.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg, according to the report. The collections process can have legal implications, present operational challenges, and ultimately impact the efficient orderly flow of business.

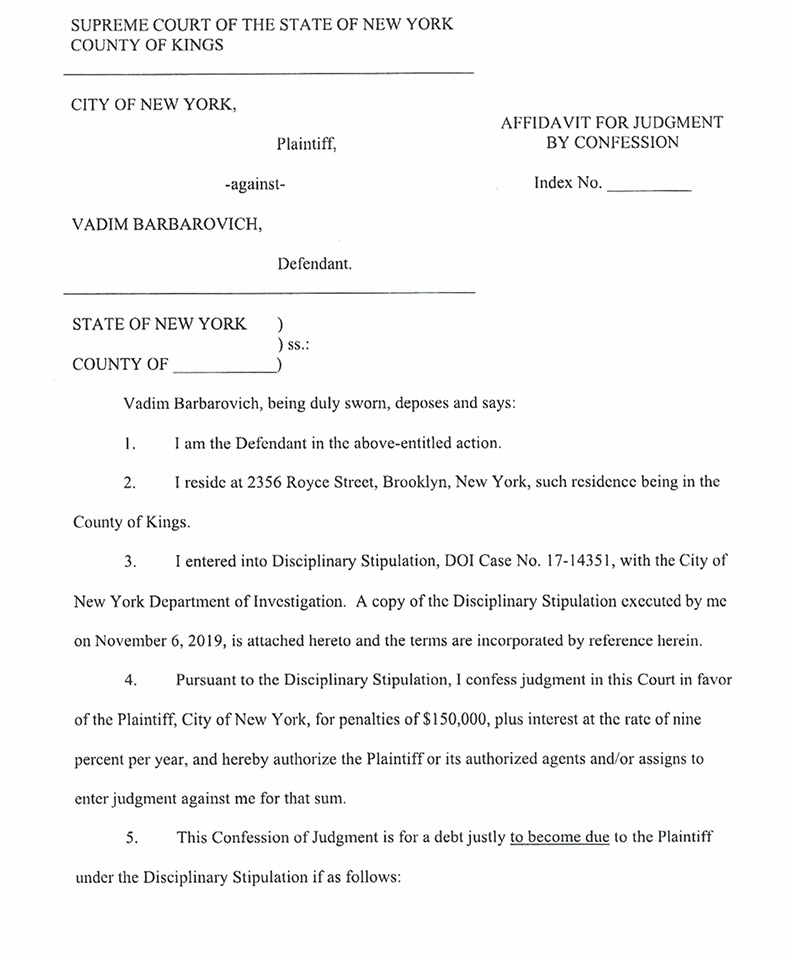

COJ Enforcer Gets COJ’d By City of New York And Is Forced to Resign NYC Marshal Position

November 7, 2019 A New York City marshal at the center of a controversial Bloomberg News story series last year about “predatory lending,” has resigned after a city probe, the City of New York announced.

A New York City marshal at the center of a controversial Bloomberg News story series last year about “predatory lending,” has resigned after a city probe, the City of New York announced.

Marshal Vadim Barbarovich was allegedly a prolific enforcer of New York judgments obtained by confession. After irregularities were discovered by the Department of Investigation with how he served levies, the City of New York formally levied penalties of their own against him that include a return of fees and poundage earned from 92 improperly served levies, his resignation, and a $300,000 fine.

The City agreed to suspend the full amount of the monetary fine provided he complies with an orderly wind-down of his business by March 20th. Barbarovich, in a twisted circumstance of irony, had to guarantee full immediate payment in the instance he did not comply…by signing a Confession of Judgment.

The investigation into Barbarovich began in May 2018, 4 months before Bloomberg News published their story, details published by the City reveal.

Earlier this year, New York State passed a law restricting COJs from being entered against non-New York state debtors.

David Goldin is BACK – The Scoop Behind His Return

November 7, 2019 “When I started, the term merchant cash advance didn’t even exist. There really were no business loans back then, the word ‘fintech’ didn’t exist, ‘alternative lender’ didn’t exist … Back in the day it was all about getting a credit facility, and that was like the iPhone 5, and now we’re the iPhone 11. There’s more ways to be a lot less stressful, a lot more productive, and a lot less time consuming. There’s other financial instruments to really help companies excel.”

“When I started, the term merchant cash advance didn’t even exist. There really were no business loans back then, the word ‘fintech’ didn’t exist, ‘alternative lender’ didn’t exist … Back in the day it was all about getting a credit facility, and that was like the iPhone 5, and now we’re the iPhone 11. There’s more ways to be a lot less stressful, a lot more productive, and a lot less time consuming. There’s other financial instruments to really help companies excel.”

This is how David Goldin speaks of the difference between the early days of the alternative funding industry, a marketplace which he helped form in the pre-crash years of the noughties, and now, a moment which sees the CEO’s return to the market after years abroad.

Having founded Capify, an alternative finance company, in 2002, Goldin had worked in the space for over a decade before he exited the US market in January of 2017, choosing to instead focus his efforts on the UK and Australia.

Over two years later, Goldin is back in the States with Lender Capital Partners, offering capital to commercial finance companies, with a priority given to those who deal in MCAs and business loans. “It’s very exciting, I’m coming in from a different perspective,” noted Goldin. “It’s still a great industry. I’m just coming at it from a different angle which I think could be a lot more productive and scale a lot faster.”

And as well as funding the funders, this new angle includes forward flow programs, a commitment to participate in deals up to $1 million, credit facilities in the range of $20-100 million, a system by which point of sale providers are able to provide merchant financing via their software, and the Broker Graduate Program. The last of these being LCP’s in-house channel open to brokers who originate a minimum of $500,000 a month, and who want to receive capital and advice from LCP in order to become a direct funder.

When asked why he chose to return via this more top-down approach to the industry, Goldin explained that “there’s enough good players here that are trying to originate on the merchant side, so rather than try to reinvent the wheel I thought I’d come in with my years of experience running a MCA alternative lending platform in the US, knowing what the pain points are.”

Made possible through a partnership with Basepoint Capital, LCP is there to help MCA and business loans companies through both the good times and the bad, according to its founder, saying that what was a lesson for him partly informs LCP’s model.

“The time to raise money is when you don’t need it. If you run into trouble where your lender gets spooked or either has their own financial issues, or it’s a regulatory or macroeconomic condition, you just can’t bring in a new lender within 30 or 60 days, and if you do it’s not going to be on favorable economic terms. It’s really going to be a desperate attempt to get it … It’s almost like having more than one internet connection in your office, if one goes down you have a backup with no downtime.”

Who Exactly Got Paid In Knight Capital’s Sale… And How Much? ($27.8M)

November 6, 2019

Update 11/7/19 9:05 AM: Ready Capital Corporation confirmed this morning that Knight Capital’s total sale price was $27.8M. $10M was in stock.

When Ready Capital Corporation acquired Knight Capital last week for $10 million in stock and an undisclosed amount of cash, questions abounded over who directly benefitted from the sale and how much cash was actually exchanged.

Documents later submitted by Ready Capital revealed that Knight Capital was owned by a San Jose, CA-fund named Len Co, LLC. Len Co began lending to Knight Capital in 2014 and later converted a large principal balance into a major equity investment in Knight in early 2018.

Several months later, Len Co’s primary creditor forced Len Co into Chapter 7. Shares in Knight, being a major asset of Len Co, became a talking point of that proceeding, ultimately propelling Knight into the hands of an eager buyer, Ready Capital Corporation.

The stock in the sale was therefore almost entirely paid out to the Estate of Len Co, LLC (640,205 of the 658,771 Ready Capital Corporation shares to be precise). This being the case was a reflection of the predicament Len Co was in, not necessarily that there was anything adverse about Knight.

On May 31, the bankruptcy court presiding over Len Co approved a proposed sale of Knight Capital to a confidential buyer for a grand total of $25 million, via $10 million in stock and a whopping $15 million in cash to be completed by December 31, 2019.

The buyer was identified as a publicly traded company. Assuming no better bids were received by Mid-August, the company would be sold for the $25 million under the terms offered to the publicly traded buyer. The court reaffirmed it on August 15th.

In October, Ready Capital Corporation announced that they had acquired 100% of Knight Capital in a deal for $10 million in stock and an undisclosed amount of cash.

Update: After this story was posted, Ready Capital confirmed on a morning earnings call that the sales price was slightly more than $25M and was finalized at $27.8M.

Merchant Cash Advance Industry Pioneer David Goldin Launches Lender Capital Partners To Provide Financing To Merchant Cash Advance / Alternative Business Loan Providers

November 5, 2019 White Plains, NY – November 5, 2019 – David Goldin, one of the merchant cash advance industry pioneers who founded one of the first US merchant cash advance providers in 2002, Capify (formerly known as AmeriMerchant), that later expanded to the UK and Australia has partnered with a subsidiary of Basepoint Capital, a seasoned specialty finance group, to form Lender Capital Partners (http://www.lendercapitalpartners.com). Basepoint has provided over $300 million in committed financings / forward flow purchases in the merchant cash advance / alternative business loan industry.

White Plains, NY – November 5, 2019 – David Goldin, one of the merchant cash advance industry pioneers who founded one of the first US merchant cash advance providers in 2002, Capify (formerly known as AmeriMerchant), that later expanded to the UK and Australia has partnered with a subsidiary of Basepoint Capital, a seasoned specialty finance group, to form Lender Capital Partners (http://www.lendercapitalpartners.com). Basepoint has provided over $300 million in committed financings / forward flow purchases in the merchant cash advance / alternative business loan industry.

Lender Capital Partners (LCP) provides MCA and alternative business lending platforms with strategic capital including:

- Forward flow programs – LCP funds 100% of the amounts disbursed by the platform in connection with their funding of advances / business loans including sales commissions to their customers to free up cash and avoid the burden of equity requirements or “hair cut” money associated with traditional asset-based credit lines.

- Participations / Syndication – by having LCP purchase a participation in larger deals, the platform is able to offer larger size approvals to their customers and brokers / referral partners without taking on concentration risk. LCP can participate up to $1 million in each deal and provide strategic capital by offering our many years of industry experience underwriting larger size deals.

- Credit facilities – LCP provide credit facilities for MCA and alternative business loan providers that begin at a minimum of $20 million and can go up to $100 million+. Our credit facilities typically offer a higher advance rate than a bank and less stringent concentration limits.

- Broker Graduation Program – LCP will allow brokers to take the next step of becoming a direct lender by providing the capital and know-how needed to fund deals on their own. Designed for brokers that can originate a minimum of $500k/month, LCP can provide the capital needed and set up brokers with one of our partners to provide a back office if needed for underwriting / servicing without having to make the investment on their own.

- Point of Sales / Credit Card Processor Merchant Cash Advance / Merchant Financing Program – LCP can provide a turnkey solution for POS / Credit Card Processing companies to offer a merchant financing program to their merchants to compete with some of the larger POS providers / credit card processors that are now offering these programs in-house and have had great success. LCP can provide the capital needed for a merchant financing / merchant cash advance program as well as introduce one of our underwriting/servicing partners if needed.

“After exiting the US MCA business in 2017, I have decided the time is right to offer my 17+ years of global MCA / business lending experience to the industry by partnering with Basepoint to supply capital to the MCA / business loan industry. I believe the various programs we offer at Lender Capital Partners are tailored for just about any company in the industry – for both current lenders as well as larger brokers/ISOs that are looking to graduate to the next step of becoming a lender as well as to POS providers / merchant acquirers looking to offer an in-house program to their merchants. And my 17+ years industry experience is a great value-added benefit that very few lenders, if any can bring to the table”, says David Goldin, a principal of Lender Capital Partners.”

About LENDER CAPITAL PARTNERS

Lender Capital Partners provides capital to commercial lenders, particularly in the merchant cash advance / alternative business loan industry. One of the founders of Lender Capital Partners is David Goldin. David is the Founder of Capify, one of the first merchant cash advance providers in the US founded in 2002. David scaled Capify to 225 employees operating in 4 countries and sold the US business to a competitor in 2017 and secured a $95 million credit facility with Goldman Sachs to fund Capify UK and Capify Australia which has over 125 employees total today operating in each of those markets. David has over 17 years experience in the merchant cash advance / alternative business finance industry and is considered a pioneer in the industry. David’s extensive expertise allows Lender Capital Partners to bring strategic value to our relationships, not just capital. For more information on Lender Capital Partners, visit http://www.lendercapitalpartners.com

Shopify Capital Originated $141M Of Loans And MCAs In Q3, Says It’s a Meaningful Part Of The Shopify Business

October 29, 2019 Shopify Capital, Shopify’s small business funding division, originated $141 million in loans and merchant cash advances last quarter, an 85% increase over Q3 last year.

Shopify Capital, Shopify’s small business funding division, originated $141 million in loans and merchant cash advances last quarter, an 85% increase over Q3 last year.

The company has now cumulatively originated $768.9M since it began funding in April 2016.

On the earnings call, Shopify COO Harley Finkelstein commented on the company’s recent initiative to fund non-Shopify payment merchants by saying that “while it’s still early, we’re seeing strong adoption from those merchants.”

“We started Shopify Capital to help solve another playing field for entrepreneurs, access to capital to grow their businesses,” he explained. “This is especially true as merchants gear up for their busiest selling season of the year.”

When asked about how funding would play a role in the company’s long term expansion and retention plans, Finkelstein said the following:

[P]art of this is making sure that we have merchants in the entirety of their journey to success, certainly things like having additional cash for things like inventory and marketing are very important to them. And there’s not too many place to get that with capital. So we think we’re helping merchants by doing this. It also serves of course as a way to retain merchants because we’re not only now their e-commerce platform or the point sale provider or the payments provider, we’re also now in some cases playing the role of their capital provider.

So this is a meaningful part of our business, and it keeps growing, and it’s certainly something we’re very proud of. And in terms of managing the risk, it’s something we keep a close eye on. We do a ton of trade forecasting and ensuring that we look at the data to update our models as we see trends changing. That being said, it’s important to remember that most of the capital that we put out there is insured by our partner EDC.

So we think that we continue to grow the capital business at the same time manage the risk and so we’re not doing anything that is outside of that loss ratio and risk exposure comfort zone that we think we have right now.

Shopify CEO Tobi Lutke later added how their Capital division adds to their Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) because merchants use funds to build their businesses.”What happens is a lot more businesses, that otherwise would not have access to loans get them and therefore actually continue building their business.”

The FTC Wants To Police Small Business Finance

October 22, 2019 On May 23, the Federal Trade Commission launched an investigation into unfair or deceptive practices in the small business financing industry, including by merchant cash advance providers.

On May 23, the Federal Trade Commission launched an investigation into unfair or deceptive practices in the small business financing industry, including by merchant cash advance providers.

The agency is looking into, among other things, whether both financial technology companies and merchant cash advance firms are making misrepresentations in their marketing and advertising to small businesses, whether they employ brokers and lead-generators who make false and misleading claims, and whether they engage in legal chicanery and misconduct in structuring contracts and debt-servicing.

Evan Zullow, senior attorney at the FTC’s consumer protection division, told deBanked that the FTC is, moreover, investigating whether fintechs and MCAs employ “problematic,” “egregious” and “abusive” tactics in collecting debts. He cited such bullying actions as “making false threats of the consequences of not paying a debt,” as well as pressuring debtors with warnings that they could face jail time, that authorities would be notified of their “criminal” behavior, contacting third-parties like employers, colleagues, or family members, and even issuing physical threats.

“Broadly,” Zullow said in a telephone interview, “our work and authority reaches the full life cycle of the financing arrangement.” He added: “We’re looking closely at the conduct (of firms) in this industry and, if there’s unlawful conduct, we’ll take law enforcement action.”

Zullow declined to identify any targets of the FTC inquiry. “I can’t comment on nonpublic investigative work,” he said.

The FTC investigation is one of several regulatory, legislative and law enforcement actions facing the merchant cash advance industry, which was triggered by a Bloomberg exposé last winter alleging sharp practices by some MCA firms.

The FTC investigation is one of several regulatory, legislative and law enforcement actions facing the merchant cash advance industry, which was triggered by a Bloomberg exposé last winter alleging sharp practices by some MCA firms.

The Bloomberg series told of high-cost financings, of MCA firms’ draining debtors’ bank accounts, and of controversial collections practices in which debtors signed contracts that included “confessions of judgment.”

The FTC long ago outlawed the use of COJs in consumer loan contracts and several states have banned their use in commercial transactions. In September, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed legislation prohibiting the use of COJs in New York State courts for out-of-state residents. And there is a bipartisan bill pending in the U.S. Senate authored by Florida Republican Marco Rubio and Ohio Democrat Sherrod Brown to outlaw COJs nationwide.

Mark Dabertin, a senior attorney at Pepper Hamilton, described the FTC’s investigation of small business financing as a “significant development.” But he also said that the agency’s “expansive reading of the FTC Act arguably presents the bigger news.” Writing in a legal memorandum to clients, Dabertin added: “It opens the door to introducing federal consumer protection laws into all manner of business-to-business conduct.”

FTC attorney Zullow told deBanked, “We don’t think it’s new or that we’re in uncharted waters.”

The FTC inquiry into alternative small business financing is not the only investigation into the MCA industry. Citing unnamed sources, The Washington Post reported in June that the Manhattan district attorney is pursuing a criminal investigation of “a group of cash advance executives” and that the New York State attorney general’s office is conducting a separate civil probe.

The FTC’s investigation follows hard on the heels of a May 8 forum on small business financing. Labeled “Strictly Business,” the proceedings commenced with a brief address by FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra, who paid homage to the vital role that small business plays in the U.S. economy. “Hard work and the creativity of entrepreneurs and new small businesses helped us grow,” he said.

But he expressed concern that entrepreneurship and small business formation in the U.S. was in decline. According to census data analyzed by the Kaufmann Foundation and the Brookings Institution, the commissioner noted, the number of new companies as a share of U.S. businesses has declined by 44 percent from 1978 to 2012.

“It’s getting harder and harder for entrepreneurs to launch new businesses,” Chopra declared. “Since the 1980s, new business formation began its long steady decline. A decade ago births of new firms started to be eclipsed by deaths of firms.”

Chopra singled out one-sided, unjust contracts as a particularly concerning phenomenon. “One of the most powerful weapons wielded by firms over new businesses is the take-it-or-leave-it contract,” he said, adding: “Contracts are ways that we put promises on paper. When it comes to commerce, arm’s length dealing codified through contracts is a prerequisite for prosperity. “But when a market structure requires small businesses to be dependent on a small set of dominant firms — or firms that don’t engage in scrupulous business practices — these incumbents can impose contract terms that cement dominance, extract rents, and make it harder for new businesses to emerge and thrive.”

As the panel discussions unfolded, representatives of the financial technology industry (Kabbage, Square Capital and the Electronic Transactions Association) as well as executives in the merchant cash advance industry (Kapitus, Everest Business Financing, and United Capital Source) sought to emphasize the beneficial role that alternative commercial financiers were playing in fostering the growth of small businesses by filling a void left by banks.

The fintechs went first. In general, they stressed the speed and convenience of their loans and lines of credit, and the pioneering innovations in technology that allowed them to do deeper dives into companies seeking credit, and to tailor their products to the borrower’s needs. Panelists cited the “SMART Box” devised by Kabbage and OnDeck as examples of transparency. (Accompanying those companies’ loan offers, the SMART Box is modeled on the uniform terms contained in credit card offerings, which are mandated by the Truth in Lending Act. TILA does not pertain to commercial debt transactions.)

Sam Taussig, head of global policy at Kabbage, explained that his company typically provides loans to borrowers with five to seven employees — “truly Main Street American small businesses” — that are seeking out “project-based financing” or “working capital.”

Sam Taussig, head of global policy at Kabbage, explained that his company typically provides loans to borrowers with five to seven employees — “truly Main Street American small businesses” — that are seeking out “project-based financing” or “working capital.”

“The average small business according to our research only has about 27 days of cash flow on hand,” Taussig told the fintech panel, FTC moderators and audience members. “So if you as a small business owner need to seize an opportunity to expand your revenue or (have) a one-off event — such as the freezer in your ice cream store breaks — it’s very difficult to access that capital quickly to get back to business or grow your business.”

Taussig contrasted the purpose of a commercial loan with consumer loans taken out to consolidate existing debt or purchase a consumer product that’s “a depreciating asset.” Fintechs, which typically supply lightning-quick loans to entrepreneurs to purchase equipment, meet payrolls, or build inventory, should be judged by a different standard.

A florist needs to purchase roses and carnations for Mother’s Day, an ice-cream store must replenish inventory over the summer, an Irish pub has to stock up on beer and add bartenders at St. Patrick’s Day.

The session was a snapshot of not just the fintech industry but of the state of small business. Lewis Goodwin, the head of banking services at Square Capital, noted that small businesses account for 48% of the U.S. workforce. Yet, he said, Square’s surveys show that 70% of them “are not able to get what they want” when they seek financing.

Square, he said, has made 700,000 loans for $4.5 billion in just the past few years, the platform’s average loan is between $6,000 and $7,000, and it never charges borrowers more than 15% of a business’s daily receipts. The No. 1 alternative for small businesses in need of capital is “friends and family,” Goodwin said, “and that’s a tough bank to go back to.”

Panelist Gwendy Brown, vice-president of research and policy at the Opportunity Fund, a non-profit microfinance organization, provided the fintechs with their most rocky moment when she declared that small businesses turning up at her fund were typically paying an annual percentage rate of 94 percent for fintech loans. And while most small business owners were knowledgeable about their businesses — the florists “know flowers in and out,” for example — they are often bewildered by the “landscape” of financial product offerings.

Panelist Gwendy Brown, vice-president of research and policy at the Opportunity Fund, a non-profit microfinance organization, provided the fintechs with their most rocky moment when she declared that small businesses turning up at her fund were typically paying an annual percentage rate of 94 percent for fintech loans. And while most small business owners were knowledgeable about their businesses — the florists “know flowers in and out,” for example — they are often bewildered by the “landscape” of financial product offerings.

“Sophistication as a business owner,” Brown said, “does not necessarily equate into sophistication in being able to assess finance options.”

Panelist Claire Kramer Mills, vice-president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, reported that the country’s banks have made a dramatic exit from small business lending over the past ten years. A graphic would show that bank loans of more than $1 million have risen dramatically over the past decade but, she said, “When you look at the small loans, they’ve remained relatively flat and are not back to pre-crisis levels.”

Mills also said that 50% of small businesses in the Federal Reserve’s surveys “tell us that they have a funding shortfall of some sort or another. It’s more stark when you look at women-owned business, black or African-American owned businesses, and Latino-owned businesses.”

On the merchant cash advance panel there was less opportunity to dazzle the regulators and audience members with accounts of state-of-the-art technology and the ability to aggregate mountains of data to make online loans in as few as seven minutes, as Kabbage’s Taussig noted the fintech is wont to do.

Instead, industry panelists endeavored to explain to an audience — which included skeptical regulators, journalists, lawyers and critics — the precarious, high-risk nature of an MCA or factoring product, how it differs from a loan, and the upside to a merchant opting for a cash advance. (To their credit, one attendee told deBanked, the audience also included members of the MCA industry interested in compliance with federal law.)

Instead, industry panelists endeavored to explain to an audience — which included skeptical regulators, journalists, lawyers and critics — the precarious, high-risk nature of an MCA or factoring product, how it differs from a loan, and the upside to a merchant opting for a cash advance. (To their credit, one attendee told deBanked, the audience also included members of the MCA industry interested in compliance with federal law.)

A merchant cash advance is “a purchase of future receipts,” Kate Fisher, an attorney at Hudson Cook in Baltimore, explained. “The business promises to deliver a percentage of its revenue only to the extent as that revenue is created. If sales go down,” she explained, “then the business has a contractual right to pay less. If sales go up, the business may have to pay more.”

As for the major difference between a loan and a merchant cash advance: the borrower promises to repay the lender for the loan, Fisher noted, but for a cash advance “there’s no absolute obligation to repay.”

Scott Crockett, chief executive at Everest Business Funding, related two anecdotes, both involving cash advances to seasonal businesses. In the first instance, a summer resort in Georgia relied on Everest’s cash advances to tide it over during the off-season.

When the resort owner didn’t call back after two seasonal advances, Crockett said, Everest wanted to know the reason. The answer? The resort had been sold to Marriott Corporation. Thanking Everest, Crockett said, the former resort-owners reported that without the MCA, he would likely have sold off a share of his business to a private equity fund or an investor.

By providing a cash advance Everest acted “more like a temporary equity partner,” Crockett remarked.

In the second instance, a restaurant in the Florida Keys that relied on a cash advance from Everest to get through the slow summer season was destroyed by Hurricane Irma. “Thank God no one was hurt,” Crockett said, “but the business owner didn’t owe us anything. We had purchased future revenues that never materialized.”

The outsized risk borne by the MCA industry is not confined entirely to the firm making the advance, asserted Jared Weitz, chief executive at United Capital Service, a consultancy and broker based in Great Neck, N.Y. It also extends to the broker. Weitz reported that a big difference between the MCA industry and other funding sources, such as a bank loan backed by the Small Business Administration, is that ”you are responsible to give that commission back if that merchant does not perform or goes into an actual default up to 90 days in.

“I think that’s important,” Weitz added, “because on (both) the broker side and on the funding side, we really are taking a ride with the merchant to make sure that the business succeeds.”

FTC’s panel moderators prodded the MCA firms to describe a typical factor rate. Jesse Carlson, senior vice-president and general counsel at Kapitus, asserted that the factor rate can vary, but did not provide a rate.

FTC’s panel moderators prodded the MCA firms to describe a typical factor rate. Jesse Carlson, senior vice-president and general counsel at Kapitus, asserted that the factor rate can vary, but did not provide a rate.

“Our average financing is approximately $50,000, it’s approximately 11-12 months,” he said. “On a $50,000 funding we would be purchasing $65,000 of future revenue of that business.”

The FTC moderator asked how that financing arrangement compared with a “typical” annual percentage rate for a small business financing loan and whether businesses “understand the difference.”

Carlson replied: “There is no interest rate and there is no APR. There is no set repayment period, so there is no term.” He added: “We provide (the) total cost in a very clear disclosure on the first page of all of our contracts.”

Ami Kassar, founder and chief executive of Multifunding, a loan broker that does 70% of its work with the Small Business Administration, emerged as the panelist most critical of the MCA industry. If a small business owner takes an advance of $50,000, Kassar said, the advance is “often quoted as a factor rate of 20%. The merchant thinks about that as a 20% rate. But on a six-month payback, it’s closer to 60-65%.”

He asserted that small businesses would do better to borrow the same amount of money using an SBA loan, pay 8 1/4 percent and take 10 years to pay back. It would take more effort and the wait might be longer, but “the impact on their cash flow is dramatic” — $600 per month versus $600 a day, he said — “compared to some of these other solutions.”

Kassar warned about “enticing” offers from MCA firms on the Internet, particularly for a business owner in a bind. “If you jump on that train and take a short-term amortization, oftentimes the cash flow pressure that creates forces you into a cycle of short-term renewals. As your situation gets tougher and tougher, you get into situations of stacking and stacking.”

On a final panel on, among other matters, whether there is uniformity in the commercial funding business, panelists described a massive muddle of financial products.

Barbara Lipman: project manager in the division of community affairs with the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, said that the central bank rounded up small businesses to do some mystery shopping. The cohort — small businesses that employ fewer than 20 employees and had less than $2 million in revenues — pretended to shop for credit online.

As they sought out information about costs and terms and what the application process was like, she said, “They’re telling us that it’s very difficult to find even some basic information. Some of the lenders are very explicit about costs and fees. Others however require a visitor to go to the website to enter business and personal information before finding even the basics about the products.” That experience, Lipman said, was “problematic.”

She also said that, once they were identified as prospective borrowers on the Internet, the Fed’s shoppers were barraged with a ceaseless spate of online credit offers.

John Arensmeyer, chief executive at Small Business Majority, an advocacy organization, called for greater consistency and transparency in the marketplace. “We hear all the time, ‘Gee, why do we need to worry about this? These are business people,’” he said. “The reality is that unless a business is large enough to have a controller or head of accounting, they are no more sophisticated than the average consumer.

“Even about the question of whether a merchant cash advance is a loan or not,” Arensmeyer added. “To the average small business owner everything is a loan. These legal distinctions are meaningless. It’s pretty much the Wild West.”

In the aftermath of the forum, the question now is: What is the FTC likely to do?

In the aftermath of the forum, the question now is: What is the FTC likely to do?

Zullow, the FTC attorney, referred deBanked to several recent cases — including actions against Avant and SoFi — in which the agency sanctioned online lenders that engaged in unfair or deceptive practices, or misrepresented their products to consumers.

These included a $3.85 million settlement in April, 2019, with Avant, an online lending company. The FTC had charged that the fintech had made “unauthorized charges on consumers’ accounts” and “unlawfully required consumers to consent to automatic payments from their bank accounts,” the agency said in a statement.

In the settlement with SoFi, the FTC alleged that the online lender, “made prominent false statements about loan refinancing savings in television, print, and internet advertisements.” Under the final order, “SoFi is prohibited from misrepresenting to consumers how much money consumers will save,” according to an FTC press release.

But these are traditional actions against consumer lenders. A more relevant FTC action, says Pepper Hamilton attorney Dabertin, was the FTC’s “Operation Main Street,” a major enforcement action taken in July, 2018 when the agency joined forces with a dozen law enforcement partners to bring civil and criminal charges against 24 alleged scam artists charged with bilking U.S. small businesses for more than $290 million.

In the multi-pronged campaign, which Zullow also cited, the FTC collaborated with two U.S. attorneys’ offices, the attorneys general of eight states, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and the Better Business Bureau. According to the FTC, the strike force took action against six types of fraudulent schemes, including:

- Unordered merchandise scams in which the defendants charged consumers for toner, light bulbs, cleaner and other office supplies that they never ordered;

- Imposter scams in which the defendants use deceptive tactics, such as claiming an affiliation with a government or private entity, to trick consumers into paying for corporate materials, filings, registrations, or fees;

- Scams involving unsolicited faxes or robocalls offering business loans and vacation packages.

If there remains any question about whether the FTC believes itself constrained from acting on behalf of small businesses as well as consumers, consider the closing remarks at the May forum made by Andrew Smith, director of the agency’s bureau of consumer protection.

“(O)ur organic statute, the FTC Act, allows us to address unfair and deceptive practices even with respect to businesses,” Smith declared, “And I want to make clear that we believe strongly in the importance of small businesses to the economy, the importance of loans and financing to the economy.

Smith asserted that the agency could be casting a wide net. “The FTC Act gives us broad authority to stop deceptive and unfair practices by nonbank lenders, marketers, brokers, ISOs, servicers, lead generators and collectors.”

As fintechs and MCAs, in particular, await forthcoming actions by the commission, their membership should take pains to comport themselves ethically and responsibly, counsels Hudson Cook attorney Fisher. “I don’t think businesses should be nervous,” she says, “but they should be motivated to improve compliance with the law.”

She recommends that companies make certain that they have a robust vendor-management policy in place, and that they review contracts with ISOs. Companies should also ensure that they have the ability to audit ISOs and monitor any complaints. “Take them seriously and respond,” Fisher says.

Companies would also do well to review advertising on their websites to ascertain that claims are not deceptive, and see to it that customer service and collections are “done in a way that is fair and not deceptive,” she says, adding of the FTC investigation: “This is a wake-up call.”