merchant financing

Hello Square Capital

March 1, 2014We’ve seen copies of this notice posted on a few websites now:

Square, the well-known micro-merchant processor with celebrity CEO Jack Dorsey is debuting a merchant cash advance program. Truthfully, I’m not surprised in the slightest. Come on in Square, the water’s fine!

What is still interesting to this day is the realization that so many small business owners have never even heard of the concept. You can check out comments by people on the mr. money mustache forum regarding Square Capital here.

Sell my future credit card sales? What the HECK?!

It’s a 16 year old industry now my friends. One of these days it’d be nice if people just knew this product existed. That seems to be the hardest part…

The Growing Divide

February 28, 2014 It wasn’t too long ago that everyone in this industry knew everyone else. If not personally, then at least through their credit inquiries or UCC names. You crossed paths and acknowledged each other. It was a small world then. Today, not so much.

It wasn’t too long ago that everyone in this industry knew everyone else. If not personally, then at least through their credit inquiries or UCC names. You crossed paths and acknowledged each other. It was a small world then. Today, not so much.

As the barriers to entry have remained low, the simplicity of ACH repayment has drawn in people by the thousands to become brokers, syndicates, and funders. Anyone can be any one of those three or all three at the same time. There’s still the originals out there, the guys who go to the trade shows and visit offices regularly to stay in touch. But then there’s another crowd, the newcomers that don’t file UCCs, attend shows, or interact much with everyone else. They’re funding a half million, a million, or even $5 million a month and no one really knows they exist except for their own clients. The merchant cash advance industry which was once a shadowy market in its own right now has its own shadowy sector within it.

At the Factoring 2014 conference in April, the President of Fora Financial is poised to debate the Business Development manager of Credit Cash on the subject of whether or not merchant cash advance transactions are true sales. The truth is that I have seen so many variations of funding contracts out on the street that the merits of that debate may be flawed. No one knows what a merchant cash advance is anymore. It’s a point I argued in You Can’t Ask How Big it Is Without Defining What it is in January’s issue of DailyFunder.

The industry is made up of people that deal in daily payments. How these deals are structured vary widely. Indeed there is a growing divide.

Emotions are running high in 2014 and some grievances are practically coming to blows. Stacking is as polarizing a debate as Obamacare. There are folks that believe there is no precedence for dealing with stacking, but stacking is as old as MCA.

Many years ago it was cut and dry. If one company purchased the future revenues of a small business, it was contractually impossible for a second company to buy that same block of future revenues. “How could someone else buy what has already been sold?” so the argument went…

In 2007-2008, stacking was a merchant problem, whereby small business owners would devise ways to get double or triple funded in a very short amount of time so that each company didn’t know about the other until long after the money had been wired. Much of the arguments in favor of stacking back then came from the merchants themselves who felt that MCA contracts bordered on being unlawfully restrictive because it prevented them from obtaining virtually any outside financing unless the MCA was satisfied in full. Without the capital to satisfy their entire outstanding MCA balance, they were locked into renewing with the same company indefinitely with little leverage to negotiate future terms, so the argument went…

Today, it’s the funding companies that bear the brunt of criticism from their peers for stacking, mainly because they do it willingly and are not being deceived by merchants. It is perceived as a funder problem.

In March of 2008 (a full 6 years ago), the Electronic Transactions Association (ETA) established the following guidelines on the issue in their MCA white paper:

In order to effectively manage risk and prevent a merchant from becoming over-extended, merchants should not knowingly be allowed to “stack” advances (obtaining an additional advance when an outstanding balance on a previous advance exists). In the event additional advances are sought, the original advance should be paid off directly to the previous Merchant Cash Advance Company [MCAC] by the new MCAC (to ensure that the merchant does not retain funds due to the previous MCAC) with a portion of the proceeds given on the current advance.

The ETA calls for many common sense standards such as fair retrieval rates, sound underwriting, and legal collections practices. The advice is timeless and I suggest everyone read it. The industry might be growing apart but many of the fundamentals are the same.

Still, with the new crowd of near-anonymous funders, it is impossible to know what everyone’s intentions are. Given the low barriers to entry, there’s also the question as to whether or not the newcomers are legally prepared to book such deals. The industry is fraught with risks and always has been.

I just hope that as the divide grows, we are all united by a common goal, acting in the best interest of small businesses.

How to Value a Merchant Cash Advance Company (or Alternative Lender)

February 9, 2014If you’re at all interested in the future of the merchant cash advance industry, you need to read Wall Street Evaluates Merchant Cash Advance in the first issue of DailyFunder. It offers a fresh perspective through the eyes of financiers outside the industry looking in.

Names include:

- Jason Gurandiano, Managing Director in Deutsche Bank’s Financial Technology Group

- David Cox, Managing Director at Evercore Partners

- Thomas McGovern, Vice President at Cypress Associates

- Steven Mandis, adjunct professor at Columbia Business School.

The article is relatively broad but it communicates some very important points:

1. Some players in the space exist as lifestyle businesses. They’re not scalable, their success is largely attributed to what the owner does for it, and company’s long term vision is to basically make sure the owner takes home a nice paycheck.

2. Some of the big players in the space are on similar growth trajectories. Nothing differentiates each of them from the pack, and none of them really have an advantage over the other.

3. EBITDA is a bad valuation measure and growth is a good one.

3. EBITDA is a bad valuation measure and growth is a good one.

On point #1, a lifestyle business is no good to a professional investor in this space. Aside from the success usually being owner-dependent, one question an investor is certain to ask a prospect is, “If I gave you $100 million today, what would you do with it?” There are many wrong answers to that question. If you said solicit more ISOs, buy more leads, or hire more sales people, they’re going to wonder why you haven’t done those things already.

On the same token, those answers would communicate that you’re going to do the exact same thing you’re already doing. It’s a mistake to think that scaling in such a manner will keep the original margins intact. It also does nothing to protect the company against change or enable it to grow exponentially.

On point #2, it’s great to be big, established, and growing at a moderate pace, but what good is that to an investor looking to double, triple, or quadruple their money? And who’s to say that a moderate growth strategy will continue as it has in the past?

Many many many (did I say many yet?) people have come into this space with visions of grandeur, to be bigger than CAN Capital in less than 24 months. What do their plans usually consist of? Pay higher than average commissions and fund deals they shouldn’t be funding. To date, none of those companies are bigger than CAN Capital and some of them are out of business. A growth plan can’t consist of funding deals you don’t want to and paying commissions you can’t afford. That’s called a suicide mission and it’s very effective.

Some big funding companies may appear sustainable on the outside but they’re woefully fragile on the inside. Jason Gurandiano said it best with this quote, “The general knock on merchant cash advance has been that they are an ISO-centric model.” I’m not discounting the value of ISOs in this business. To some extent they rule the roost, and that’s the problem in the eyes of investors. Many merchant cash advance companies rely on a handful of symbiotic relationships. The ISO relies on the funding company for commissions and the funding company relies on the ISO for deals. But what happens if:

- The ISO is enticed with higher commissions or better service with somebody else

- The ISO’s deal flow slumps

- The ISO goes out of business

- The ISO uses unscrupulous sales practices when selling the funding company’s product

- The ISO uses their relationship as leverage on the funding company to make bad decisions

- The funding company needs to reduce commissions but the ISO can’t sustain it

An ISO-dependent merchant cash advance company doesn’t have much control over growth. Believe me, I’ve been on those phone calls where the ISO is asked to send more business. But what happens if they have no more to send? Or what if they would just rather do most of their business elsewhere?

Again, there is absolutely nothing wrong with a purely ISO-centric model in general, but it is much less attractive to investors looking to do a deal in this industry and that’s the theme of this post.

Point #3 is unique because it addresses the how to value a company once you’ve found one worth investing in. Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA) is not a viable valuation formula here as it doesn’t make sense to measure the worth of a company dependent on expensive debt by stripping away the cost of that debt.

Point #3 is unique because it addresses the how to value a company once you’ve found one worth investing in. Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA) is not a viable valuation formula here as it doesn’t make sense to measure the worth of a company dependent on expensive debt by stripping away the cost of that debt.

According to Aswath Damodaran, debt to a financial service company should be treated like a raw material. In his 2009 paper, Valuing Financial Services Firms, he states, “debt is to a bank what steel is to a manufacturing company, something to be molded into other products which can then be sold at a higher price and yield a profit.” It is a perfect analogy for a merchant cash advance company.

Damodaran’s analysis covers a range of situations but I find an Asset Based Valuation intriguing. It states, “How would you value the loan portfolio of a bank? One approach would be to estimate the price at which the loan portfolio can be sold to another financial service firm,” There isn’t a lot of precedent for that in this industry unfortunately. Damodaran continues though with, “but the better approach is to value it based upon the expected cash flows.” For certain, one would have to take into account the renewal rate, renewal commissions, the average recovery timeframe, and the default rate.

If you bought $100 million in RTR today, how much would you get back 1 year from now or 2 years from now? This number is going to differ from company to company.

An Asset Based Valuation might be in order for a funding company that is winding down and shedding its existing portfolio, but it’s not appropriate for one with growth. One should assume that they’re buying a growing business when investing in a merchant cash advance company, not a packaged portfolio.

One question an investor might ask is, “what am I buying?” The average merchant cash advance company can be perceived as nothing more than a vehicle to maximize the spread between revenue and borrowing costs. They’re not really businesses in the traditional sense, more like arbitrageurs. They buy leads and/or they pay commissions, there are some fixed costs, but there’s not a whole lot more to it. There are virtually no barriers to entry and anybody can replicate the model. So you invest in the people who are doing it currently and their system (assuming it’s working so far). The value of that might only be equivalent to 1x – 4x annual profit. Why pay more when competition can drag margins down, regulations could disrupt the space in the future, or the investor could just as easily start their own company with the funds they have instead?

With that said, the average merchant cash advance company is more attractive to a lender than an equity investor. Additionally, they can also offer a nice monetary return by allowing people to participate in the funding of individual deals. Both are indeed what many investors choose to do, either lend money to these companies or syndicate. Why buy the cow when you can get the milk for free?

Merchant Cash Advance companies that make the headlines with big equity investments are not average. They create value, rather than just engage in arbitrage. They’re building something, changing something, disrupting something. They don’t profit off spreads in the market, they create the market and dominate it. Today this typically happens through technology, and not just any technology, but technology that leads to substantial future earnings. There’s a difference between spending a million dollars on a platform to make things more efficient and spending a million dollars on a platform that causes earnings to increase by 1,000%. Too many companies view technological investments in the former sense, a cost that eats into the spread instead of one that can blow the roof off of it.

Investors are looking for companies that plan to soar from Point A to Z, not ones that are moseying along from A to B.

RapidAdvance was said to have gotten an Enterprise Valuation in excess of $100 million when being acquired by Rockbridge Growth Equity. For the most part that number reflects Total Debt + Total Equity – Cash. When you buy a company, you’re buying their debts as well. 90% of their enterprise value could potentially have been the value of their outstanding debts. Of course I doubt it was, but it should put their eye opening valuation into perspective.

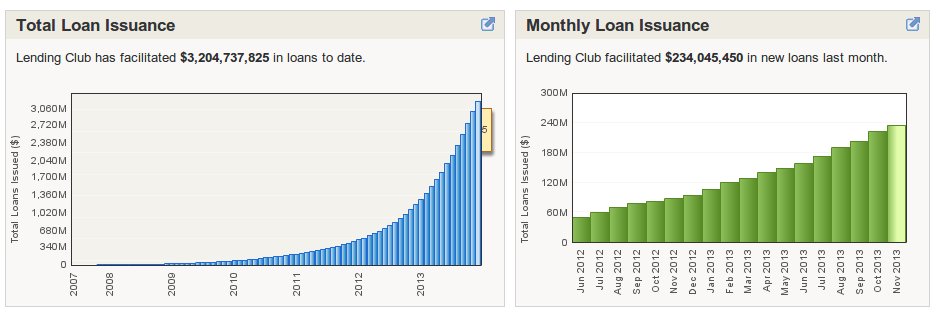

Contrast the RapidAdvance deal with the most recent valuation of Lending Club at $2.3 billion. Lending Club earns substantially lower returns per deal but they have an engine for growth that is virtually unmatched. In the month of August 2012, they booked $70 million in loans. In January of 2014, they booked $258 million. That’s 3.7x the monthly volume they were doing less than 18 months ago. That’s what an investor calls an opportunity.

How do you value a merchant cash advance company? There’s no easy way to do it and it largely depends on whether or not they’re an arbitrage shop chugging along or one creating substantial value.

There’s plenty of free milk out there. Why would someone pay top dollar for your cow?

– Merchant Processing Resource

Will Peer-to-Peer Lending Burn the Alternative Business Lending Market?

January 12, 2014For months I’ve been saying that peer-to-peer lenders will be companies to look out for, the latest being on December 29th. Lending Club fully intends to make the leap from consumer lending to business lending which may possibly pit them against the world of merchant cash advance.

In this video, a Bloomberg reporter asks OnDeck Capital’s CEO if his company will get burned by peer-to-peer lending.

If you watched the whole thing, you might also hear the insinuation that OnDeck’s product is similar to factoring since Breslow explains his loan program much like a merchant cash advance account rep would. “You simply pay x cents on the dollar”

I think there is room for both Lending Club and OnDeck. It’s the little funders of the world that will eventually feel a squeeze.

2014 Starts off With a Case of Red bull

January 10, 2014 Woah, slow down there fellas. Let us digest one thing at a time. We’re not even 2 weeks into the new year and already we’ve learned that:

Woah, slow down there fellas. Let us digest one thing at a time. We’re not even 2 weeks into the new year and already we’ve learned that:

CAN Capital raised another $33 Million (but that they didn’t need it?)

Merchant Cash Advance was the the feature story on the front page of the Wall Street Journal. Seriously…

Bloggers are learning about this industry for the first time. They’re having a bit of trouble getting it right.

PayPal, which just recently kicked off its own merchant cash advance program (or as they call it, their Working Capital Program) has already issued 4,000 advances.

Regulators are freaking out over the use of social media information in loan approvals.

DailyFunder will begin mailing out the first alternative business lending magazine a week from today. It’s free so sign up!

Forget Fancy Algorithms, Give the Merchants a Psych Exam

January 1, 2014Select an answer to each of the following questions:

1. When faced with financial hardship during the course of my loan, I would do the following:

(a) Do nothing and hope my luck changes.

(b) Call the bank and block all debits from the lender and wait for the lender to call me about it.

(c) Change my phone number, hide, and avoid making anymore loan payments at all costs.

(d) Call the lender to inform them of my hardship.

(e) Sell my business and let the lender sort it out with the new owner.

2. The IRS sends you a letter that says they believe you understated your income last year and owe back taxes. As a result I would do the following:

(a) Ignore the letter until it becomes a more pressing issue.

(b) Consult with my accountant/lawyer.

(c) I didn’t file a tax return last year.

(d) Pretend I never got it.

(e) Pay whatever is owed.

—-

Congratulations! based on the answers you chose you have been approved!

—-

According to the New York Times, Banks in 16 countries are using psychometric tests to gauge the creditworthiness of applicants in lieu of credit reports. That’s because the criteria used to score credit in the U.S. is not always available abroad, particularly in developing nations.

According to the New York Times, Banks in 16 countries are using psychometric tests to gauge the creditworthiness of applicants in lieu of credit reports. That’s because the criteria used to score credit in the U.S. is not always available abroad, particularly in developing nations.

There isn’t necessarily a right or wrong answer to each test question. Instead an algorithm measures the loan repayment performance statistics of each answer and learns to approve or decline based on those selections by applicants in the future. Interesting isn’t it? The questions wouldn’t be easy to manipulate either since they are currently psychological. Applicants are asked for example how strongly they believe in or disbelieve in fate.

Would such an idea have legs for alternative business lending in the U.S.? I think there’s something to it. I can say from experience that in my former lifetime as an underwriter, our team would rarely read from a script during a merchant interview. Instead we would engage applicants in a conversation about their business to gauge their attitude and determine the level of commitment to their work. You’d be surprised what this approach would reveal.

In this context, business owners would share that they had no idea whether or not they were losing money, that they planned on closing the business if the advance didn’t turn things around, that they didn’t care about previous loans that they defaulted on, that they weren’t even the person running the business day to day but rather the name on all the paperwork because they had good credit, or that they were using the money to fund a vacation to the carribean because the business was failing and they wanted to get away. We did make sure to steer the conversation towards the requirements on our checklist, but the final decision on borderline deals was often decided on this call.

Some funders use this interview call just to confirm information on the application, but it should no doubt play a role in a deal approval. That’s just my opinion. Once the deal is funded though, it will all come down to fate, hard work, or coincidence. I guess it all depends on how strongly the merchant agreed or disagreed with each of those on the exam.

Underwrite at your own risk.

Peer-to-Peer Lending Will Meet MCA Financing

December 29, 2013 In 2014 the peer-to-peer lending industry will collide with merchant cash advance and the rest of alternative business lending. Get familiar with these names: Lending Club, Funding Circle, and Prosper. They are brothers and sisters in the business of non-bank financing. They’re also seasoned, tested, and much like the merchant cash advance industry, experiencing phenomenal growth.

In 2014 the peer-to-peer lending industry will collide with merchant cash advance and the rest of alternative business lending. Get familiar with these names: Lending Club, Funding Circle, and Prosper. They are brothers and sisters in the business of non-bank financing. They’re also seasoned, tested, and much like the merchant cash advance industry, experiencing phenomenal growth.

The old guard of merchant cash advance companies should take notice. After losing significant ground to Kabbage and OnDeck Capital, a new breed of fighter is about to enter the ring. I hear this phrase too often in response to the threat of competition, “there’s enough opportunity out there for everyone.”

But is there? Aside from the ACH repayment boom, one of the biggest drivers of merchant cash advance industry growth has been stacking. Stacking is the process of issuing an additional advance or loan to a merchant without paying off their existing advances or loans. That puts merchants in the position of having 2, 3, 4, or even 5 daily withdrawals to remain in good standing with all of them.

While the legality and risks of stacking have long been debated, the deeper revelation here is that there may not be as much new opportunity as everyone thinks. There has been an ongoing turf war over land that had already been discovered. It’s caused overall annual funding volume to rise significantly, but there’s not much room for 400%, 500% or 1,000% growth.

Funders like Kabbage came in and conquered the online merchant cash advance space without anyone noticing. Some funders have taken 5 years to double output on a monthly basis. Impressive, yes, but Lending Club on the other hand has more than quadrupled monthly funding volume over just the last 18 months. Not only that, but they’re doing more than OnDeck and CAN Capital (formerly Capital Access Network) combined. That’s massive.

Backed by Google and recently valued at $2.3 Billion, Lending Club is expected to go public in the next 12 months. As they seek to extend their dominance from consumer lending to business lending, funders should seriously ask themselves, is there really enough opportunity out there for everyone?

The Achilles Heel for merchant cash advance companies is money. Regardless of how fast they turn it over, there’s no possible way to experience fast triple digit growth without outside capital. Some funders spend a lot of time and energy trying to raise it. Others are content without it and go chugging along at a moderate pace.

Peer-to-peer lenders on the other hand have a unique advantage, unlimited access to cash. That’s because they source all the money from individuals. The money is crowdsourced from an infinite pool of investors and they just book the deals and service them. Combine this model with a sweet infusion from an IPO and alternative business lending will have its very own behemoth.

Peer-to-peer lenders on the other hand have a unique advantage, unlimited access to cash. That’s because they source all the money from individuals. The money is crowdsourced from an infinite pool of investors and they just book the deals and service them. Combine this model with a sweet infusion from an IPO and alternative business lending will have its very own behemoth.

I’m not predicting the doom of merchant cash advance at the hands of Lending Club, but quite the opposite. Lending Club will legitimize non-bank business financing once and for all. Merchants will seek capital and investors will seek lucrative returns. Merchant cash advance companies offer a vastly better ROI than what 3-5 year loans can do with regulated interest rates. The top 10 Prosper investors are only earning 15-19%.

Lending Club will carpet bomb businesses across the nation with marketing and likely end up declining 90% of them. If they do indeed stick to their model of 3-5 year loans, they will undoubtedly leave a trail of interested but unfundable merchants. Alternative lenders and merchant cash advance companies will rush in to fill the void.

At the same time, that capital raising problem could fix itself. As everyone jumps on the peer-to-peer/crowdsourcing bandwagon, investors will be thrilled to learn that merchant cash advance is peer-to-peer based as well. Oh you didn’t know? Many funders already crowdsource capital from “syndicates”. Syndication in merchant cash advance is a simplified form of crowdsourcing. ISOs, investors, and account reps can pool funds collectively into deals just as someone could with Prosper or Lending Club.

I first raised this similarity in December 2010 (three years ago!) and even went so far as to make a mock version of Prosper’s site with MCA terminology plastered on it. Eerie isn’t it?

The difference between a company like Lending Club and say a company like RapidAdvance is whether or not funding is meant to be used as working capital or permanent capital.

The consumer lending model is not applicable when it comes to underwriting businesses. Renaud Laplanche, the CEO of Lending Club acknowledged that when he testified before congress a few weeks ago. But is he really ready to experience it for himself?

We shall see in 2014 when the line blurs once and for all. MCA, say hi to your family, P2P.

—————

Get familiar:

Merchant Cash Advance Term Used Before Congress

December 18, 2013 I’d like to think that the term, merchant cash advance, is mainstream enough that a congressman would know what it was. I have no idea if that’s the case though. What I do know is that Renaud Laplanche, the CEO of Lending Club gave testimony before the Committee on Small Business of the United States House of Representatives on December 5, 2013.

I’d like to think that the term, merchant cash advance, is mainstream enough that a congressman would know what it was. I have no idea if that’s the case though. What I do know is that Renaud Laplanche, the CEO of Lending Club gave testimony before the Committee on Small Business of the United States House of Representatives on December 5, 2013.

Watch:

In it, he argued that small businesses have insufficient access to capital and that the situation is getting worse. We knew that already. However, he went on to explain that alternative sources such as merchant cash advance companies are the fastest growing segment of the SMB loan market, but issued caution that some of them are not as transparent about their costs as they could be.

The big takeaway here is that he didn’t say they are charging too much, but rather that some business owners may not understand the true cost. I often defend the high costs charged in the merchant cash advance industry, but I’ll acknowledge that historically there have been a few companies that have been weak in the disclosure department. That said, the industry as a whole has matured a lot and there is a lot less confusion about how these financial products work.

Typically in the context Laplanche used, transparency is code for “please put a big box on your contract that states the specific Annual Percentage Rate” of the deal. That’s good advice for a lender and in many cases the law, but for transactions that explicitly are not loans, filling in a number to make people feel good would be a mistake and probably jeopardize the sale transaction itself. If I went to Best Buy and paid $2,000 in advance for a $3,000 Sony big screen TV that would be shipped to me in 3 months when it comes out, should I have to disclose to Best Buy that the 50% discount for pre-ordering 3 months in advance is equivalent to them paying 200% APR?

This is what happened: I advanced them $2,000 in return for a $3,000 piece of merchandise at a later date.

I got a discount on my purchase and they got cash upfront to use as they see fit. Follow me?

Now instead of buying a TV, I give Best Buy $2,000 today and in return am buying $3,000 worth of future proceeds they make from selling TVs. That’s buying future proceeds at a discounted price and paying for them today. As people buy TVs from the store, I’ll get a small % of each sale until I get the $3,000 I purchased. If a TV buying frenzy occurs, it could take me 6 months to get the $3,000 that I bought. But if the Sony models are defective and hardly anyone is buying TVs, it could take me 18 months until i get the $3,000 back.

In the first situation, if the TV never ships I get my $2,000 back. In the second situation if the TV sales never happen, I don’t get the 3 grand or the 2 grand. I’ll just have to live with whatever I got back up until the point the TV sales stopped, even if that number is a big fat ZERO.

Best Buy is worse off in the first situation, but critics pounce on the 2nd situation. APR, it’s not fair! Transparency, high rate, etc.

Imagine if every retailer that ever had a 30% off sale or half price sale one day woke up and realized the sale they had was too expensive and not transparent enough for them to understand what they were doing. If only consumers had given the cashiers a receipt of their own that explained that they would actually only be getting half the money because of their 50% off sale, then perhaps the store owners would have reconsidered the whole thing. 50% off over the course of 1 day?! My God, that’s practically like paying 18,250% interest!!!

To argue that a business owner might not understand what it means to sell something for a discount is like saying that a food critic has no idea what a mouth is used for.

I will acknowledge that issues could potentially occur if an unscrupulous company marketed their purchase of future sales as if it were a loan. That could lead to confusion as to what the withholding % represents and why it was not reported to credit bureaus. I’m all in favor of increasing the transparency of purchases as purchases and loans as loans, but let’s not go calling purchases, loans. Americans should understand what it means to buy something or sell something. Macy’s knows what they’re doing when they have a Black Friday Sale. They do a lot of business at less than retail price. They are happy with the result or disappointed with it. They’re business people engaged in business. End of the story.

In recent years, the term, merchant cash advance, has become synonymous with short term business financing, whether by way of selling future revenues or lending. When testimony was entered that many merchant cash advance providers charge annual percentage rates in excess of 40%, I do hope that Laplanche was speaking only about transactions that are actually loans. As for any fees outside of the core transaction, those should be clear as day for both purchases and loans. I think many companies are doing a good job with disclosure on that end already.

Part 2

The other case that Laplanche made was brilliant. Underwriting businesses is more expensive than it is to underwrite consumers. Consumer loan? Easy, check the FICO score and call it a day. That methodology doesn’t even come close to working with businesses. He stated:

These figures show that absolute loan performance is not the main issue of declining SMB loan issuances; we believe a larger part of the issue lies in high underwriting costs. SMBs are a heterogeneous group and therefore the underwriting and processing of these loans is not as cost efficient as underwriting consumers, a more homogenous population. Business loan underwriting requires an understanding of the business plan and financials and interviews with management that result in higher underwriting costs, which make smaller loans (under $1M and especially under $250k) less attractive to lenders.

Read the full transcript:

LendingClub CEO Renaud Laplanche Testimony For House Committee On Small Business

Merchant Cash Advance just echoed through the halls of Capitol Hill. And so it’s become just a little bit more mainstream, perhaps too maninstream.

Thoughts?