Sean Murray is the President and Chief Editor of deBanked and the founder of the Broker Fair Conference. Connect with me on LinkedIn or follow me on twitter. You can view all future deBanked events here.

Articles by Sean Murray

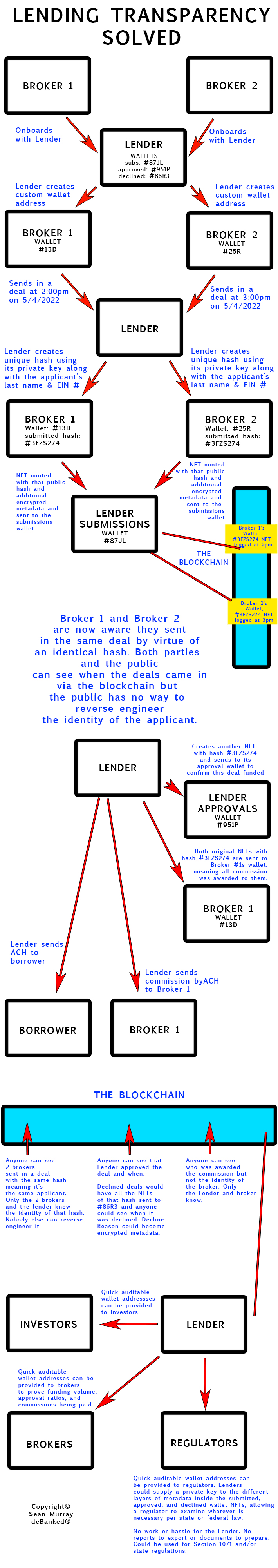

Lender / Broker Ecosystem Transparency Solved

May 4, 2022What happens when a broker sends in a deal and is told it’s declined, only to find out that it was approved and funded for another broker? Usually, a very angry post on social media. The problem is that everyone wants maximum transparency, but how to get it? Who can trust who? What can be done? When will someone do it?

Well, call me insane, but I’ve taken a crack at solving it. And don’t get mad at me because I use the word blockchain because I promise this is not about crypto. Everything would still be ACH-based and recorded just as you already do it, but this little piece of tech would sit underneath it without any manual effort. All automated. No work. Also, it’s possible I’m just totally wrong or have missed some possibilities. You be the judge. Realistic or dream world?

1. Brokers and Merchants don’t need to use the blockchain or know how to use it.

2. A dev at a lender justs need to understand digital wallet addresses and a little feature about them called Non-Fungible Tokens to build or implement a third-party add-on of this. (These “NFTs” have nothing to do with art, they are just uniquely identifiable text files logged into the blockchain with metadata inside them.)

First, here’s my diagram:

Here’s what it’s doing:

1. When brokers sign up with a lender, the lender assigns a uniquely identifiable blockchain wallet address to them on an automated basis.

2. When a broker sends in a deal, the lender creates a unique encrypted hash of the applicant’s bare minimum identifiable data (like last name and EIN #). This hash is placed into a text file in plain english along with the applicant’s application data encrypted. (also automated).

3. The lender creates a Non-Fungible Token from the broker’s wallet address and sends it to the lenders’s official submission wallet. (automated). This wallet will show the NFTs for every deal ever submitted to this lender. Nobody will be able to reverse engineer info about the deals and only the broker who submitted the deal will be aware of what the hash of the deal is. This gives them a chance to view exactly when their deal was logged and if there’s any duplicate hashes in the wallet that would signal that same deal had already been submitted by someone else and when it was submitted.

4. If the deal is approved by the lender, the lender pays the broker and funds the merchant via ACH like normal. Then the lender creates an NFT with the same public hash and sends that one to its approval wallet. The original NFT sent to its submissions wallet is now sent to the broker’s wallet, signaling that they have been awarded the commission on this deal. (automated).

5. If the deal is declined, the lender creates an NFT with the same public hash and all the NFTs for this deal are sent to the decline wallet, signaling that the deal was killed and nobody was awarded the commission on it. (automated).

Every deal’s NFT has to eventually be moved to approved or declined. They can’t sit in submissions in perpetuity.

End result: brokers that submit deals can see if their deal has been submitted before and when it was submitted. Brokers can verify if the deal was funded, when, and if commissions were paid to someone. No actual money is changing hands via crypto (though there might be transactions fees to move NFTs around.) Investors and regulators can also examine the flow and if necessary, be given access to a private key so that they can unlock and view the metadata in the submissions, approvals, and declines themselves.

Naturally, everyone’s first question is: what happens if the lender tries to bypass this?

1. A broker who submits a deal that does not see an NFT created for it in the lender’s submissions wallet, already knows that the lender is trying to operate outside the system. Time to move on!

2. A lender that shows a deal was declined and commissions paid to nobody could be easily discovered if the borrower shows a statement with proof that they received a deposit. No need to speculate what happened. Time to move on!

3. A broker that submitted a deal first can show that its deal was logged first in the submissions wallet. Anyone on social media or the public square could also confirm that and the lender could not manipulate the data to play favorites.

4. Lenders that operate outside of it would show little-to-no submissions or approval volume, signaling to a broker that for some reason they do not want the anonymized data auditable.

5. Lenders that are not real that go around pretending to be a lender just to scoop up deals would be hard-pressed to provide the three verifiable wallet addresses showing the volume of submissions, approvals, declines, and the respective ratios for the latter two. If they can’t show that they’ve ever done any deals or paid commissions, even if you can’t see what the individual details are, they’re not real.

6. After a lender moves the deal’s NFT to a broker’s wallet to signal they’re being awarded the commission, it’s possible the lender does NOT actually ACH the broker the commission. In that case, the broker would have a nice verifiable public display that shows it was supposed to be paid the commission for all to see. Public pressure ensues.

7. If the lender secretly pays a broker the commission but then publicly marks the deal as declined so that another broker who sent in the same deal doesn’t suspect what happened, well then the broker who got paid is going to be suspicious that the lender could do the same thing to them. There’s an incentive to be honest.

8. Merchants need not know about any of this. It doesn’t concern them.

9. The broker does not interact with the blockchain in any way except in the case it just wanted to view the data.

10. The lender does not have to manually interact with the blockchain at all. The system would just be bolted on to an existing CRM. It would do all the above by itself.

New Domain Name Gold Rush Sets Up Possible Battle for Future of SMB Finance

April 25, 2022 If you could have businessloan.com or businessloans.com as your website, would you jump on the opportunity to get it?

If you could have businessloan.com or businessloans.com as your website, would you jump on the opportunity to get it?

It’s evident that the market for keyword-based domains has evolved over time. Couldn’t get the .com? You could’ve tried to get the less coveted .net or .org. Don’t like those? Today, you can get the .business, .deals, .financial, .loan, .loans, or hundreds of other customized tlds. With so many to choose from, most experts in the field would advise that if you don’t own the .com version, to not even bother getting cute with customizations for your brand or keyword because customers will just get confused.

But recently, another domain name market has quietly been gaining steam. It’s for something called a .eth, an Ethereum blockchain-based crypto address shortener by the Ethereum Name Service. It’s not necessarily something one could use to build a website with, at least not yet. Originally envisioned as a way to condense long impossible-to-remember crypto wallet addresses into memorable words, users have started to buy up a bunch of keywords that may be familiar to deBanked readers. Just to name a few:

- businessloan.eth

- businessloans.eth

- smbloans.eth

- merchantcashadvance.eth

- ach.eth

- syndication.eth

- lending.eth

- ppploan.eth

- underwriting.eth

- brokers.eth

- loanbroker.eth

- mca.eth

- factoring.eth

- funding.eth

- backdoored.eth

At face-value, this might appear to be a vanity crypto play, one in which one could send crypto to your-name-here.eth instead of trying to type out a long address like: 0x64233eAa064ef0d54ff1A963933D0D2d46ab5829. But an ENS domain name holds much more potential than just that. It’s moving towards becoming the backbone of one’s identity in the upcoming era of the web called web 3.0 (web3 for short). Instead of having to remember passwords for hundreds of websites, identity can be validated through one’s digital wallet. Such a concept is not theoretical. It’s already being used.

Take seanmurray.eth for example. You could send eth, bitcoin, litecoin, or dogecoin to it, but at the same time it’s connected to an email address and a url (this one). Plus it’s linked to an NFT avatar (broker #7 from The Broker NFT collection) which is in that wallet. I can use it to do an e-commerce online checkout in 5 seconds without ever needing to enter any payment information even if I’ve never visited the site before. It’s faster than PayPal and with less steps involved. I can connect it to my twitter account, OpenSea, or use it to vote in an official poll without ever having to create an account on something. The wallet is the identity verification. The .eth name, therefore, has the potential to become the defining baseline of who or what one is on the internet. Not theoretically. It’s already happening.

Take seanmurray.eth for example. You could send eth, bitcoin, litecoin, or dogecoin to it, but at the same time it’s connected to an email address and a url (this one). Plus it’s linked to an NFT avatar (broker #7 from The Broker NFT collection) which is in that wallet. I can use it to do an e-commerce online checkout in 5 seconds without ever needing to enter any payment information even if I’ve never visited the site before. It’s faster than PayPal and with less steps involved. I can connect it to my twitter account, OpenSea, or use it to vote in an official poll without ever having to create an account on something. The wallet is the identity verification. The .eth name, therefore, has the potential to become the defining baseline of who or what one is on the internet. Not theoretically. It’s already happening.

Crypto is already starting to creep into the small business finance industry. In August, a funding company announced that it would begin offering commissions and fundings in crypto because of the speed potential. Far from being a gimmick, brokers started to choose crypto payments over ACH or a wire because of how fast it would be. There’s also no chargeback risk with crypto.

Currently, the owner of mca.eth has listed the domain for sale on OpenSea at a price of 20 eth (approximately $60,000). That’s less than what MerchantCashInAdvance.com sold for in 2011. Perhaps the value of an Ethereum Name Service domain holds less promise than a website that ranked well on Google in 2011. But then again, being well ranked on Google is not as important as it used to be. It’s impossible to say what, if any impact web3 will have on the small business finance industry long term, but for now there are those out there quietly buying up names like ach and funding and syndication on the chance that they will become something.

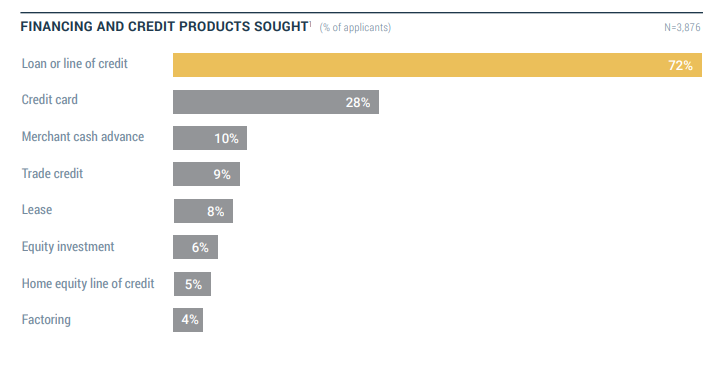

Ten Percent of Small Businesses That Sought Financing in 2021 Sought a Merchant Cash Advance

April 18, 2022A whopping 10% of small businesses that sought financing last year sought out a merchant cash advance, according to the latest study published by the Federal Reserve. That figure was up from 8% in 2020 and 9% in 2019. For the the preceding years, that figure had held fairly consistent at 7%. [See 2015, See 2017]. Market penetration, therefore, has arguably increased by about 40% since 2015.

Meanwhile, the percentage of applicants that sought out leasing has gone down over the last seven years: from 11% in 2015 to 8% in 2021. Factoring has hovered around 3-4% consistently.

The pursuit of of loans and lines of credit decreased dramatically from 89% in 2020 to 72% in 2021. And approvals have gone down across the board. Approvals on business loans, lines of credits, and MCAs hit a peak of 83% in 2019 and plunged to 76% in 2020, the first year of Covid. The figure fell even further in 2021, down to 68%. Online lenders and large banks had the lowest approval rates overall, at 51% and 48% respectively.

Maryland’s Commercial Financing Disclosure Bill Failed to Move Forward

April 12, 2022 Maryland’s commercial financing bill, propelled by bi-partisan support, failed to overcome the final hurdle before the State’s 2022 legislative session adjourned sine die yesterday. SB 825 passed the Senate in March and became the subject of much debate in the House of Delegates on the 30th. Testimony from 17 people was considered, much of it oral.

Maryland’s commercial financing bill, propelled by bi-partisan support, failed to overcome the final hurdle before the State’s 2022 legislative session adjourned sine die yesterday. SB 825 passed the Senate in March and became the subject of much debate in the House of Delegates on the 30th. Testimony from 17 people was considered, much of it oral.

The bill’s lofty idyllic intent is perhaps what contributed to its demise. Despite legislative enthusiasm for applying consumer style protections to commercial finance transactions, regulators tasked with its actual implementation were amongst its harshest critics.

The Consumer Protection Division of the State’s Attorney General’s Office said “the bill makes a violation an unfair, abusive or deceptive practice in violation of the Consumer Protection Act. With limited exceptions, violations of the Consumer Protection Act are limited to consumer transactions, i.e., transactions that are primarily for personal, family or household use, and expanding the CPA to cover business-to business transactions would open a door that could lead to a significant increase in the number of complaints received by the Division, requiring the Division to add corresponding resources.” The Division gave an official thumbs down on the bill.

Maryland’s Department of Labor stated that the requirements of the bill would make it “difficult to operationalize from a monitoring, investigatory and enforcement perspective” and that there would be too much uncertainty given that New York, a state that passed a similar law, has been unable to effectively implement their own version. “Maryland small businesses, lenders and borrowers alike, may be negatively impacted if the rollout of the system in New York is significantly delayed or New York enacts systems or procedures not appropriate to or anticipated by Maryland businesses,” it concluded.

Other states, like California, have encountered similar problems with commercial financing disclosure legislation. The bill it passed in 2018 still has not been implemented over lingering disputes over how to do the math it mandates.

Proponents and critics alike picked away at each other’s arguments in Maryland, but when the session ended late late Monday evening to a hail of confetti and balloons, SB 825 had not been called. This was the third year in a row that a commercial financing bill has failed. Another version will likely be introduced when the legislature eventually returns.

Relying on Google Maps to Verify a Merchant’s Business? Be Careful

April 5, 2022 If a Google Maps listing inspired confidence in a small business loan applicant’s existence, then you may not know just how many people try to create fake profiles. In 2018, for example, Google acknowledged that it had removed more than 3 million fake business listings from its platform while simultaneously disabling 150,000 accounts that created them. At the time, industry experts told the Wall Street Journal that Google’s efforts were hardly making a dent, estimating that on any given business day, 11 million businesses listed on Google Maps were fake.

If a Google Maps listing inspired confidence in a small business loan applicant’s existence, then you may not know just how many people try to create fake profiles. In 2018, for example, Google acknowledged that it had removed more than 3 million fake business listings from its platform while simultaneously disabling 150,000 accounts that created them. At the time, industry experts told the Wall Street Journal that Google’s efforts were hardly making a dent, estimating that on any given business day, 11 million businesses listed on Google Maps were fake.

Some fake business types are more common than others. Sources told the WSJ that contractors, electricians, towing and car repair services, movers, and lawyers ranked among those most used in a scheme.

Since then, efforts to trick Google have become even more prolific. Google revealed that more than 7 million fake business profiles were removed in 2021, more than double that of three years earlier. The company also caught schemers in the act of trying to create new fake business listing more than 12 million times in 2021.

These results should be alarming for a small business lender that is unable to conduct an on-site visit or mobile site inspection with an applicant. For smaller sized applications, a cursory check on Google Maps or Google Street View to scope out the business location may be the only visual analysis that an underwriter conducts. Mismatches on Street View can be explained away by claiming that the Google car hadn’t come by recently to refresh the pictures or that the signs on the building hadn’t been changed or gone up yet, but the listing itself on Google Maps might imply that the business must be there, even if the Google car hadn’t come by lately. Obviously, as the data shows, that’s not perfectly reliable.

Online reviews, meanwhile, have already been the subject of skepticism for years, with there being allegations of companies manipulating reviews. Savvy searchers might read such attestations and conclude that a company’s positive testimonials are fake and perhaps the products or services being offered are not as good as they’re being artificially acclaimed to be. Google said that it removed 95 million “policy-violating reviews” in 2021. That’s on top of blocking 190 million photos and 5 million videos.

“Every day we receive around 20 million contributions from people using Maps,” Google said in its announcement “Those contributions include everything from updated business hours and phone numbers to photos and reviews. As with any platform that accepts contributed content, we have to stay vigilant in our efforts to fight abuse and make sure this information is accurate.”

“Every day we receive around 20 million contributions from people using Maps,” Google said in its announcement “Those contributions include everything from updated business hours and phone numbers to photos and reviews. As with any platform that accepts contributed content, we have to stay vigilant in our efforts to fight abuse and make sure this information is accurate.”

Despite the immense number of fraudulent listings, Google touts that it amounts to less than 1% of all the total listings on Google Maps. That’s perhaps reassuring news to anyone that relied on the data in the past to make a crucial decision. The danger, however, is that schemers are trying to create more fakes, not less, and it may only take a handful of applications to slip through the cracks of underwriting to realize one can never get too comfortable with an external data point.

A restaurant with twenty identically worded reviews about how good the soup is, for example, might trigger one’s skepticism radar about it actually being all that good. “Ah, ha,” you might say, “they’re trying to cover up the fact that something is wrong with their soup!” And that’s where they’ve got you, because while you’re busy playing soup detective, you’re completely missing the real con. There isn’t even any soup at all, the restaurant itself doesn’t even exist.

Banks and Retailers Are Secretly Evaluating Your Eyes

April 1, 2022April Fools 2022

Last December, a leaked pitch deck from a boutique investment bank ended up in the hands of a veteran tech reporter for Scribner’s Gazette. Kirby Fitzpatrick, who spent much of the past year covering the Buy-Now Pay-Later beat, laughed when he saw that the package sent to him anonymously was titled “Eye-Now Pay-Later.” Fitzpatrick said he groaned when he read a note that was attached. “You have to see it to believe it,” it said.

Last December, a leaked pitch deck from a boutique investment bank ended up in the hands of a veteran tech reporter for Scribner’s Gazette. Kirby Fitzpatrick, who spent much of the past year covering the Buy-Now Pay-Later beat, laughed when he saw that the package sent to him anonymously was titled “Eye-Now Pay-Later.” Fitzpatrick said he groaned when he read a note that was attached. “You have to see it to believe it,” it said.

Inundated with promotional press packets on a daily basis, Fitzpatrick said that the pitch was literally so corny that he was driven to take a look through it. He was glad that he did. The slides had a link to a demo on the staging server of a well-known national bank. The instructions were very simple, look into the camera of your computer and think about the happiest moment of your life for 10 seconds and then click “submit.” So he did.

The only thing that popped up on the next page was a number. It said 250.

“I had no idea what that was supposed to represent or mean,” Fitzpatrick said, “but the next slide said to go back and repeat the process but this time to think about the worst moment of your life.” Playing along, he clicked submit and was greeted by a new number, this time 5. It’s the next slide that opened his eyes to what the game was. The technology had somehow determined that his happy moment was worth more than his worst and the numbers represented the optimal price that a consumer should be presented for a fictional product where the retailer could still profit.

“You are more likely to pay a higher amount for something that will bring you extreme happiness,” the next slide said.

In the retail world, this is obvious information. The challenge, according to Fitzpatrick, is that big data knows what you clicked on and what you’re looking for, but it doesn’t have a great way to judge just how bad you want it and how happy it would make you. “You clicked on the dress, you compared prices on the dress, but a retailer has no way of listening into the debate playing out inside your head. They don’t know if it’s the dress you had always imagined yourself in or if you’re just looking for something to hang in the closet with no particular function in mind.”

In the retail world, this is obvious information. The challenge, according to Fitzpatrick, is that big data knows what you clicked on and what you’re looking for, but it doesn’t have a great way to judge just how bad you want it and how happy it would make you. “You clicked on the dress, you compared prices on the dress, but a retailer has no way of listening into the debate playing out inside your head. They don’t know if it’s the dress you had always imagined yourself in or if you’re just looking for something to hang in the closet with no particular function in mind.”

Intrigued, Fitzpatrick called the bank that hosted the demo to inquire if such a concept had ever gone anywhere.

“By the next day,” Fitzpatrick complained, “I was told by my editor that I was suspended from my position and was locked out of my work accounts. The bank apparently accused me of a security breach and I was basically in trouble. I couldn’t believe it.”

But later that night his editor showed up at his house, knocking discreetly on his backdoor and holding his finger up to his lips when Fitzpatrick answered. The story, it seemed, was still alive, but had to be taken to someone bigger like the Wall Street Journal or the New York Times. The Gazette was out of its league.

The bigger papers, backed by powerful legal defense teams, assigned its top journalists to collaborate with Fitzpatrick. Within weeks, the collective determined that the technology was real and that it relied on measuring minuscule changes in pupil dilation to gauge happiness. It was all about the eyes.

“We thought the science was cool and we worried about how this could impact consumers if something like this were ever used in the future,” Fitzpatrick said. “We thought we had a cautionary consumer advocate story brewing but then we were shocked by what we learned next.”

The team found that a handful of mobile-first web-based retailers had already been using it and that the phone cameras of shoppers were being activated as they browsed these sites. The only way to see the price of an item was to click the picture of it and by then the technology had already analyzed their eyes to determine how much it was desired. The price they’d see on the next page reflected the retailer’s cost plus the analyzed margin of desire.

The team tried to game the system to see just how much they could make the prices change based on what they were thinking. The widest variation was achieved on a polyester scarf, which for one reporter was $39 and another was $799. “Nobody dared ask what kind of happy thoughts activated a price of 800 bucks,” the Gazette editor joked. “But I don’t think it was his ex-wife.”

The team tried to game the system to see just how much they could make the prices change based on what they were thinking. The widest variation was achieved on a polyester scarf, which for one reporter was $39 and another was $799. “Nobody dared ask what kind of happy thoughts activated a price of 800 bucks,” the Gazette editor joked. “But I don’t think it was his ex-wife.”

Once again, the team thought it had its story wrapped up, until it discovered the technology was hiding in plain sight. Amidst all the html, javascript, and tracking cookies, was a tag embedded in the website [!slooflirpa] that activated the cameras and the technology behind it. The worry was that the team started finding the code all over the web, including on the websites of big box retailers and department store chains.

“We looked at the archived page of a retailer that had gone out of business in 2016 and saw that the code had been on its website even then,” Fitzpatrick said. “That shocked us to think that this could’ve been going on almost six years ago. It sounded impossible even. I started to think about everything I had overpaid for online over the years and shuddered at the ‘what if.'”

The editor of another large paper stunned the room into silence when he asked what year Apple had first released an iPhone with front-facing cameras. “We had to look it up and the answer was 2010,” Fitzpatrick said. “At that point, it was like ‘folks, what are we looking at here? Is this something that everyone already knows? Is this just how things work and I’m the only person who never knew?'”

The collective sought out help from an optical technology firm to get an opinion on their findings so far. Ekaf Eman, CEO of SEKOJ Vision, confirmed that not only was such pupil technology possible but that there had also been a huge rush for retailers to buy camera equipment that was capable of it.

“We did consulting for a lot of these stores,” Eman said, “and we assumed they wanted it to identify shoplifters and reduce theft, etc. but every time we brought up the technology in a security context, they were like ‘wait, security? oh right, yes, security, sure yes put it down as that.’ It was very suspicious but we didn’t think anything of it at the time.”

“I asked Mr. Eman if he worked on this before or during covid,” Fitzpatrick said. “And he says ‘covid? ha, oh long before… this was back in ’96 or ’97.'”

It was then that the collective took a step back, suspecting that it had possibly stumbled upon a national intelligence or homeland defense operation that it had inadvertently mistaken for something else. While awaiting to hear back from the FBI before proceeding further, the investment banker who authored the original pitch deck showed up at the office of Scribner’s Gazette. Having recently been let go, he laughed when he heard the reporters argue that the whole thing smelled like a CIA operation.

Kip, the banker’s preferred pseudonym, said that retailers had already moved far beyond price and were already using the tech to generate interest rate proposals on loans. “You ever hear of Buy-Now Pay-Later?” he asked. “That’s the latest frontier for eye analysis.”

Kip said that when he first started in the field, the technology was being used to gauge if an in-person consumer had looked at the price of an item on the shelf. And if not, it then assessed pupil dilation to determine how much it was desired. The desire was translated into a price that was then transmitted to the cash register they went to.

“I didn’t really believe it myself when I first learned about it,” said Kip, “but a friend of mine named Billy once partook in the intake of a certain substance and then decided he really needed to buy a pair of socks at the mall. So he gets to the register and the cashier, wide-eyed, tells him it’ll be $3,500. Billy just pulls out his Amex card and swipes it like it was nothing. Then he ripped open the pack and proceeded to put the new pair on his feet right there in the checkout lane. So I said, ‘damn, how are those socks Billy?!’ and he told me that they were freaking amazing.”

“I didn’t really believe it myself when I first learned about it,” said Kip, “but a friend of mine named Billy once partook in the intake of a certain substance and then decided he really needed to buy a pair of socks at the mall. So he gets to the register and the cashier, wide-eyed, tells him it’ll be $3,500. Billy just pulls out his Amex card and swipes it like it was nothing. Then he ripped open the pack and proceeded to put the new pair on his feet right there in the checkout lane. So I said, ‘damn, how are those socks Billy?!’ and he told me that they were freaking amazing.”

The tech company who built the algorithm reportedly contacted Kip afterwards to let him know that his friend Billy had actually reached a perfect score of happiness.

“This technology changes lives,” Kip said. “Billy told everyone he’s ever met about how he once walked around in a thirty-five-hundred-dollar pair of socks. He’s very proud of it. I didn’t have the heart to tell him how much I paid for the exact same pair.”

Fitzpatrick, of the Gazette, asked Kip how he approaches shopping knowing what he knows about the entire scheme.

“I only shop while mad and sad, just downright miserable,” Kip replied. “One time I cried until the same pair of socks was only 50 cents. Billy asked me how they were. I told him they were the worst, just the absolute worst.”

deBanked Sets Record With Miami Event

March 26, 2022deBanked welcomed nearly 700 attendees in Miami this past Thursday, easily making it the largest deBanked CONNECT event in the company’s history. The record registrations put it on par with Broker Fair, the annual conference that takes place in New York City.

More than half of all attendees to deBanked CONNECT MIAMI were small business finance brokers.

The mantra heard around the show was that the industry is BACK!

deBanked conducted dozens of live interviews on the red carpet, including several with cast members of Equipping The Dream, the industry’s first reality TV show. All interviews will be made available on deBanked TV over the course of the week.

We’ll have the full photos and more available as soon as possible! Thank you to everyone who attended, spoke, and sponsored. And stay tuned for more news from deBanked. 😎

Welcome to deBanked CONNECT MIAMI

March 23, 2022

For those that are registered and in town for deBanked CONNECT MIAMI, allow me to welcome you. Here’s what’s going on:

March 23: Start connecting with other attendees via the event mobile app.

March 23 (10:00 AM): Golf at Miami Shores Country Club for those that registered in advance.

March 24 (1:00 PM): Check-in/sponsor showcase opens/event begins at the JW Marriott Marquis in Downtown Miami

March 24 (2:30 PM): Opening Remarks

March 24 (2:40 PM): Panels/speakers kick off

March 24 (6:00 PM): Cocktail reception begins and continues until 8pm

March 24 (8:30 PM+): Private & public after-parties not affiliated with the event

The March 24th full agenda can be viewed here.

What else is happening

- deBanked TV will be streaming LIVE from the event. Feel free to approach the crew to potentially be interviewed by deBanked TV host Johny Fernandez for the chance to be heard by everyone watching from home or their office. If you’re one of the people not here, goto debanked.com/tv in the afternoon of March 24th.

- Meet the cast of Equipping The Dream, the industry’s first reality show that follows four aspiring brokers at a week-long sales training. Episode 1 can be viewed HERE.

- Network in BOTH of the sponsor showcase rooms.

- Kosher food will be available. Just ask!

Got questions? Email events@debanked.com. Responses will be very slow on event day. You can also flag down a deBanked CONNECT team member in person.