Archive for 2019

Shopify Capital Issued $87.8M in Merchant Cash Advances in Q1

April 30, 2019Shopify’s small business funding division, Shopify Capital, issued $87.8 million in merchant cash advances in the first quarter of 2019, according to the company’s earnings report. The figure is a 45% increase over the same period last year. Overall, the company has funded more than $535 million in MCAs since inception.

Shopify is primarily an e-commerce platform, but they are quickly becoming a competitor to both Square and PayPal, both of whom also offer funding solutions.

College Students Abandon Student Loans, Offer Share Of Their Future Income Instead

April 29, 2019 At Purdue University, home of the Boilermakers, there’s a brick bell tower that stands high above everything else on this handsome campus of stately college buildings and green lawns. Paul Laurora, a senior Chemical Engineering student, said the bell rings on the hour and at 20 minute intervals throughout the day, as that’s when classes begin and end. And at 5 p.m., the bell rings out the melody of Purdue’s school song, “Hail Purdue.” That’s a lot of bell ringing. Laurora is a fraternity member, he lives with seven other roommates in a house on campus and he really likes film. He’s also a part of Purdue’s “Back a Boiler” Income Share Agreement (ISA) program, which is an alternative to a student loan. An ISA is an arrangement where college students pay a percentage of their future earnings to the college and other investors.

At Purdue University, home of the Boilermakers, there’s a brick bell tower that stands high above everything else on this handsome campus of stately college buildings and green lawns. Paul Laurora, a senior Chemical Engineering student, said the bell rings on the hour and at 20 minute intervals throughout the day, as that’s when classes begin and end. And at 5 p.m., the bell rings out the melody of Purdue’s school song, “Hail Purdue.” That’s a lot of bell ringing. Laurora is a fraternity member, he lives with seven other roommates in a house on campus and he really likes film. He’s also a part of Purdue’s “Back a Boiler” Income Share Agreement (ISA) program, which is an alternative to a student loan. An ISA is an arrangement where college students pay a percentage of their future earnings to the college and other investors.

Laurora was introduced to the ISA program by Purdue. It launched in 2016 and was the first of its kind. He said he signed up for it because he was denied student loans by banks and because he said the ISA is more transparent and easier to obtain.

Laurora was introduced to the ISA program by Purdue. It launched in 2016 and was the first of its kind. He said he signed up for it because he was denied student loans by banks and because he said the ISA is more transparent and easier to obtain.

“If I hadn’t gotten the ‘Back a Boiler’ ISA, I would have had to take a semester off to work to contribute to my tuition,” Laurora said.

Purdue’s ISA program works such that the percentage of a student’s future earnings that go to repaying the advance is based on the amount of money they are likely to make given their major. But the math works out such that all graduates are expected to pay roughly the same minimum amount. The graduates are given six months to find employment and then the clock starts ticking, like the one inside the campus bell tower.

As a senior, Laurora has been on an active job search. Earlier last week, he said he wasn’t too concerned about paying off his ISA, but he said it was definitely a factor when considering different jobs and their salaries. Last Friday, Laurora got a job offer from a Washington, D.C. firm to be an Engineering Technology Analyst, and he feels comfortable that he’ll earn enough money for himself while still being able to give a percentage of his salary to the ISA.

For Laurora, he is required to give 2.57% of his income for a little more than 7 years. What Laurora and other students find attractive about Purdue’s ISA Program is that, like all ISA programs, there is a time cap (usually 10 years) after which the graduate no longer owes money. The program simply concludes.

Florin Handelman is a junior at Purdue who wanted to go there because of its prestigious engineering program. He ended up switching his intended major to Industrial Design, which he’s very passionate about. He’s even part of a student club where upperclassmen mentor underclassmen in industrial design.

Florin Handelman is a junior at Purdue who wanted to go there because of its prestigious engineering program. He ended up switching his intended major to Industrial Design, which he’s very passionate about. He’s even part of a student club where upperclassmen mentor underclassmen in industrial design.

Handelman also has an ISA, which he said he really likes because of the time cap. But he noted a potential downside – which is that if you end up making far more than what Purdue anticipated, you still pay the same percentage on your income, which could end up being a lot more than a fixed-rate student loan. He conceded, though, that earning far more than expected is “an ok problem to have.” For extremely high earners, Purdue has a cap so that no one pays more than 2.5 times the principal amount they were given.

Handelman said that none of his friends have an ISA and that, unless you’re applying for financial aid, “no one really knows about it.”

Since 2016, Purdue’s “Back a Boiler” program has served over 500 students with 820 contracts for a total amount of almost $10 million, according to Tim Doty, Director of Public Information and Issues Management at Purdue. Last year’s freshman undergraduate class had more than 8,000 students, so 500 in the ISA program altogether is still a very small number. But the program has been growing steadily. And in the time since Purdue launched the first ISA program, there are now about 25 other ISA programs at institutions of higher education in the U.S., according to Charles Trafton, co-founder of Edly, a new online marketplace that connects ISA investors.

Since 2016, Purdue’s “Back a Boiler” program has served over 500 students with 820 contracts for a total amount of almost $10 million, according to Tim Doty, Director of Public Information and Issues Management at Purdue. Last year’s freshman undergraduate class had more than 8,000 students, so 500 in the ISA program altogether is still a very small number. But the program has been growing steadily. And in the time since Purdue launched the first ISA program, there are now about 25 other ISA programs at institutions of higher education in the U.S., according to Charles Trafton, co-founder of Edly, a new online marketplace that connects ISA investors.

Purdue is a public school, so tuition is less expensive in general, particularly for in-state students. For the 2018-19 academic year, tuition for in-state students was $9,992 a year and $28,794 a year for out-of-state students.

“College is ridiculously priced in general,” said Laurora, who is an out-of-state student from New Jersey. “I have a friend who’s paying $80,000 a year at NYU.”

Savanna Williams is an in-state junior and an Elementary Education major at Purdue. She’s also a member of a sorority and is an officer in a student run dance club. One thing Williams said she likes about the ISA program is that if she wants to start a family and not work for a few years, she wouldn’t owe money then. With Purdue’s program, a graduate can take off time and not pay for up to five years. But the ISA payment term is then extended for however long a period that the graduate stopped working.

Given their shared experience and future commitments, students in Purdue’s ISA program are kind of like members of a club. When Laurora was at Harry’s Chocolate Shop, a popular bar near campus, he ran into someone he knew who was in the program.

“We said hi and both agreed it was helpful.”

Does Your Merchant Cash Advance Company Pass The Scrutiny Test?

April 29, 2019

The merchant cash advance business has come under repeated fire of late from regulators, legislators and customers. “Every aspect of the industry is under scrutiny right now. Syndication agreements, underwriting, and collections are the subject of bills in Congress and across multiple states,” says Steven Zakharyayev, managing attorney for Empire Recovery Services in Manhattan, which offers debt recovery services to financial companies. So how should funders respond amid these obstacles? Here are a few pointers to help funders succeed despite ongoing challenges from a legal, regulatory, business and public relations perspective:

DIFFERENTIATE BETWEEN CASH ADVANCES AND LOANS AND MODEL BUSINESS DEALINGS ACCORDINGLY

In the eyes of the law, merchant cash advances and loans are very different. With a cash advance, a funder advances the merchant cash in exchange for a percentage of future sales, plus a fee. A loan, on the other hand, is a lump sum of cash in exchange for monthly payments over a set time period at an interest rate that can be fixed or variable. While the two types of funding options have certain similarities, funders have to be extremely careful to make appropriate distinctions in their business practices; otherwise legal trouble can easily ensue, experts say.

Most funders know that they are supposed to draw a bright line between merchant cash advance and lending, but it’s critical they put this knowledge into practice. Funders have to ensure the distinction is evident in their business lexicon, says Gregory J. Nowak, a partner in the Philadelphia office of law firm Pepper Hamilton LLP who focuses on securities law.

For example, it’s extraordinarily important that funders don’t refer to merchant cash advances as loans in their business dealings. Business records, emails and other documents can be requested in litigation for discovery purposes. If the funder’s internal documentation refers to cash advances as loans, it’s going to be hard for the company to argue that they aren’t, in reality, loans.

For example, it’s extraordinarily important that funders don’t refer to merchant cash advances as loans in their business dealings. Business records, emails and other documents can be requested in litigation for discovery purposes. If the funder’s internal documentation refers to cash advances as loans, it’s going to be hard for the company to argue that they aren’t, in reality, loans.

“Most judges want to see consistency of treatment and that includes your vocabulary,” Nowak says. “The word ‘loan’ should be banned from their email and Word files.”

There’s a fair amount of litigation surrounding what is and what isn’t a cash advance. This can be helpful guidance for funders in setting out the criteria they need to follow to be able to defend their activities as cash advances. Even so, the line is somewhat of a moving target and funders need to be stalwart in these efforts given heightened regulatory scrutiny, experts say.

“If it looks like a loan, the law will treat it as a loan—and all the consequences that follow such a determination,” says Christopher K. Odinet, an associate professor of law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law.

BE CAREFUL ABOUT YOUR COLLECTION POLICIES

Obviously companies want to collect their payments. But some funders are too quick to file lawsuits, which could lead to unwanted trouble, says Paul A. Rianda, who heads a law firm in Irvine, Calif.

“The business model of sue first, ask questions later can be a problem,” says Rianda, whose clients include merchant cash advance companies.

The concern is that when funders sue, merchants start talking to attorneys and that could open the MCA firm to other types of lawsuits. The more a funder sues, the more it increases media attention and invites examination by state regulators and others. “You invite class action lawsuits and regulatory scrutiny that you really don’t want. It’s a boomerang thing,” he says.

The issue is especially pertinent now as legislators grapple with how to handle the thorny issue of confessions of judgement, more popularly known as COJs. For instance, since the start of the year, New York courts and county clerks have become much more rigid in processing confessions of judgments.

Certainly, not all funders use COJs. Just recently, for instance, Greenbox Capital suspended the use of COJs indefinitely, in response to the heightened industrywide debate over their use. While there’s no all-encompassing directive to stop using COJs, experts say it is incumbent upon funders to ensure they are used in a responsible and proper manner, especially amid political and regulatory uncertainty.

For instance, it would be irresponsible and potentially actionable to execute on a COJ simply because the merchant doesn’t remit receivables the merchant cash advance company purchased because he didn’t generate receivables, says Catherine M. Brennan, a partner at the law firm Hudson Cook LLP in Hanover, Maryland.

To be lawful, the COJ has to be based on a breach of performance under the agreement. Fraud, for instance, is actionable. But simple failure to remit receivables because the business has failed is not, she says.

“Conflating those two things—breaches of repayment versus performance—leads to a world of hurt,” she says. “MCA transactions do not have repayment as a concept.”

In places like New York, where COJs are more controversial, funders have to be especially careful about using them properly, experts say. Even though COJs are still enforceable under New York law for the time being, funders should understand every county processes them a bit differently, says Zakharyayev of Empire Recovery Services. “If they have a preferred county for filing, they should ensure their COJs are not only compliant with state law, but also complies with local rules,” he says.

What’s more, funders should ensure their COJs are properly notarized under New York law, ensure party names and the amount confessed is accurate, and avoid blanket statements such as naming each and every county in New York as a possible venue for filing, he says.

While some funders have suggested changing their venue provisions to a COJ-friendly state if New York outlaws COJs, Zakharyayev says he recommend New York funders keep their venue in New York regardless since it would still be one of the most efficient states to enforce a judgment. “I’ve filed COJs outside of New York and, even without a COJ, New York is much more efficient in judgment enforcement as New York courts are less restrictive in allowing the judgment creditor to pursue the debtor’s assets,” he says.

BE CAREFUL WHEN RAISING THIRD-PARTY MONEY

Aside from their dealings with merchants, funders also have to be cautious when it comes to interactions with potential investors.

Some companies have ample balance sheets and don’t need money from third parties to fund their operations. But funders that decide for business purposes to solicit money from investors, have to be careful not to run afoul of SEC rules, says Nowak, the attorney with Pepper Hamilton.

He recommends funders treat these fundraising efforts as if they are issuing securities and follow the rules accordingly. Otherwise they risk being the subject of an enforcement action where the SEC alleges they are raising money using unregulated securities. “You need to be very careful here because these rules are unforgiving. You can’t ignore them,” Nowak says.

TACKLE ACCOUNTING CHALLENGES

Accounting is another business challenge many funders face. Some have fancy customer relationship management systems, but the systems aren’t always set up to provide the detailed information the accounting department’s needs to effectively reconcile the firm’s books, says Yoel Wagschal, a certified public accountant in Monroe, New York, who represents a number of funders and serves as chief financial officer at Last Chance Funding, a merchant cash advance provider.

Ideally, a funder’s CRM and accounting systems should be integrated so both sales and accounting receive the relevant data without the need for either department to input duplicate data. The two systems need a way to get information from each other, without someone manually entering the data in both systems, which is inefficient and prone to error, Wagschal says.

DON’T SKIMP ON LEGAL SERVICES

There’s no set standard for funders to follow when it comes to legal advice. Some funders have in-house counsel, some contract with external law firms and some don’t have attorneys at all, which, of course, can be a risky proposition.

Some funders use contracts they’ve poached from a reputable funder online or from a friend in the industry, says Kimberly M. Raphaeli, vice president of legal operations at Accord Business Funding in Houston, Texas. The trouble is what flies in one state may not be legal in another, she says.

Many contracts include things such as jury waivers and class-action waivers or COJs and depending on the state, the rules surrounding the enforcement of these types of clauses may be different. So it’s really important to know the nuances of the state you’re doing business in and even potentially the states where your merchants are located, she says.

Having dedicated legal staff is arguably better. But at the very least, funders should have an attorney on speed dial who can provide advice on contracts, compliance and other areas of their business. Even when a funder has in-house attorneys, Raphaeli says it’s a good idea to tap external counsel to review documents in situations where potential liability exists. Not only does this offer a second set of eyes, it can provide added peace of mind. “A funder should never shy away from paying a little bit of money for long-term business security,” Raphaeli says.

FOLLOW BEST PRACTICES

The Small Business Finance Association, an advocacy group for the non-bank alternative financing industry, has developed a list of best practices for industry participants to follow. These encompass principles of transparency, responsibility, fairness and security.

The Small Business Finance Association, an advocacy group for the non-bank alternative financing industry, has developed a list of best practices for industry participants to follow. These encompass principles of transparency, responsibility, fairness and security.

“It’s a very competitive market and companies are trying to differentiate themselves. I think it’s important to make sure you’re following industry standards,” says Steve Denis, executive director of the association whose members include funders and lenders.

Funders also need to be mindful that best practices can change based on business and competitive realities, so it’s important for funders to review procedures periodically, says Raphaeli, of Accord Business Funding. Because the industry is fast-moving, a good rule of thumb might be for a funder to review the entire set of policies and procedures every 18 months. But more frequent review could be necessary if outside factors such as new case law or regulation demand it, she says.

“Periodically taking a look at your collections techniques, your default procedures, even your funding process down to your funding call – these are all critical components of having a successful MCA funder,” she says.

TAKE PAINS TO AVOID INDUCTION INTO THE PUBLIC HALL OF SHAME

While there is no shortage of unseemly news stories involving MCA, funders need to do their best to avoid negative press. This means being extra careful about the way they present themselves to businesses, at public speaking engagements, at conferences, industry trade shows, brokers and others, says Denis of the Small Business Finance Association.

Denis, a long-time Washington, D.C., resident, recommends funders invoke what he calls the “The Washington Post test,” though it applies broadly to any news outlet. Before sending an email, leaving a voicemail or saying anything publicly, funding company employees need to ask themselves: Am I comfortable with that information being on the front page of the paper? “I think our industry has a big problem with public relations right now,” he says. “The stigma is only as true as our industry allows it to be.”

Has PayPal Eclipsed OnDeck in Small Business Loans?

April 26, 2019

It’s been said that Kabbage is on pace to surpass OnDeck in small business loan originations, but PayPal has already done it.

When PayPal announced a working capital program in the Fall of 2013, few were predicting that the initiative would propel them to the top of the small business lending charts. Just two years later, however, the payment processing giant had already loaned more than $1 billion to small businesses.

Today, that number is over $10 billion, according to a comment made by PayPal CEO Dan Schulman on the company’s Q1 earnings call.

That figure would suggest that they had loaned approximately $9 billion from Fall 2015 to the end of Q1 2019. OnDeck, by comparison, loaned $7.5 billion since Fall 2015 through Q4 2018. Several other data sources, including previous statements from PayPal that they had surpassed more than a billion dollars in quarterly small business funding in 2018 (already more than OnDeck), indicate that PayPal has become #1 on the deBanked small business funding leaderboard.

PayPal’s growth was helped in part by its acquisition of Swift Capital in 2017.

Two of the top four are payment processors:

| Company Name | 2018 Originations | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | |

| PayPal | $4,000,000,000* | $750,000,000* | ||||

| OnDeck | $2,484,000,000 | $2,114,663,000 | $2,400,000,000 | $1,900,000,000 | $1,200,000,000 | |

| Kabbage | $2,000,000,000 | $1,500,000,000 | $1,220,000,000 | $900,000,000 | $350,000,000 | |

| Square Capital | $1,600,000,000 | $1,177,000,000 | $798,000,000 | $400,000,000 | $100,000,000 | |

| Funding Circle (USA only) | $500,000,000 | |||||

| BlueVine | $500,000,000* | $200,000,000* | ||||

| National Funding | $427,000,000 | $350,000,000 | $293,000,000 | |||

| Kapitus | $393,000,000 | $375,000,000 | $375,000,000 | $280,000,000 | ||

| BFS Capital | $300,000,000 | $300,000,000 | ||||

| RapidFinance | $260,000,000 | $280,000,000 | $195,000,000 | |||

| Credibly | $180,000,000 | $150,000,000 | $95,000,000 | $55,000,000 | ||

| Shopify | $277,100,000 | $140,000,000 | ||||

| Forward Financing | $125,000,000 | |||||

| IOU Financial | $91,300,000 | $107,600,000 | $146,400,000 | $100,000,000 | ||

| Yalber | $65,000,000 |

*Asterisks signify that the figure is the editor’s estimate

< 5% Annual Returns On Small Business Loans?

April 25, 2019 If you were to invest in small business loans with 4-year terms, what kind of return would you hope to get?

If you were to invest in small business loans with 4-year terms, what kind of return would you hope to get?

Retail investors that put their money in a mix of high-risk and low-risk loans on Funding Circle’s UK platform should expect to achieve a return of 4.5% to 6.5% a year (after defaults and 1% servicing fee), the company recently announced. That’s down from their previous projections. Meanwhile, their conservative loans could achieve returns of 4.3% to 4.7% a year.

A Marcus By Goldman Sachs savings account in the UK by comparison earns 1.50%

Funding Circle explained in a blog post that the returns could actually be higher or lower than projected.

To-date, investor interest has continued to grow with peers on the platform investing £1.5 billion in 2018 and £419 million in the 1st quarter of 2019.

Lending Club Calls It Quits On Underwriting Small Business Loans

April 23, 2019

Lending Club will no longer be underwriting small business loans, according to Lending Club Head of Communication VP Anuj Nayar. The company will still accept applications for them, but will direct them instead to Opportunity Fund and Funding Circle in exchange for referral fees. Less established businesses, or those with lesser credit, will be sent to Opportunity Fund, while more established businesses with better credit will go to Funding Circle.

According to Nayar, there will be no layoffs. Some employees who had worked in small business underwriting will move elsewhere within Lending Club while others will become contractors for Opportunity Fund. Opportunity Fund is a non-profit with the mission of investing in small businesses that have been shut out of the financial mainstream. It is backed by major financial institutions including Bank of America, Goldman Sachs and the JP Morgan Chase and Knight Foundations. In fiscal year 2017, Opportunity Fund made over $92.5 million in loans to more than 2,900 small business owners.

“[These two partnerships] enables us to both deliver greater value to our applicants and capture a new revenue stream for Lending Club, while further simplifying our business and setting the stage for more partnerships and innovations for Club Members,” said Lending Club CEO Scott Sanborn.

The new revenue stream Sanborn refers to is the referral fees Lending Club will get from its new funding partners when they fund loans sent to them from Lending Club. And Lending Club’s business will be streamlined as it jettisons small business lending backend operations. They will now focus exclusively on consumer loans, which has been the company’s primary business since it was founded in 2006.

Lending Club expanded into small business lending several years ago, but this component of its business never really took off, and was declining over the last few years. At the end of December 2016, Lending Club’s non-consumer loan originations (including small business loans) accounted for 10% of its business. In December 2017, it was 9%. And in the fourth quarter of 2018, it was 7%.

Nayar said that these new partnerships will allow Lending Club to focus even more on consumer lending. Headquartered in San Francisco, Lending Club has lent more than $44 billion to 2.5 million customers.

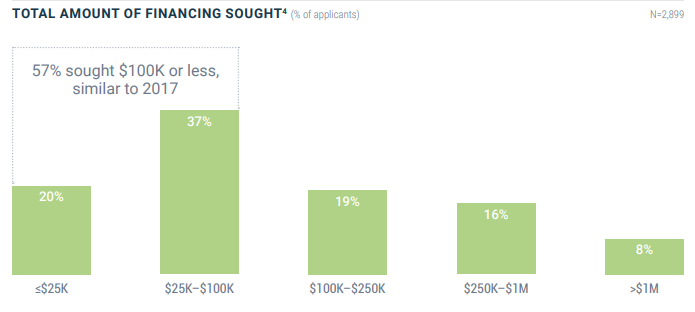

More Than Half of Small Businesses Seek Less Than $100,000 in Financing

April 22, 2019 Small businesses need capital in small doses. That’s a takeaway of the latest study published by the Federal Reserve that revealed 57% of employer firms (with less than 500 employees) that applied for financing in 2018, sought $100,000 or less. 20% sought less than $25,000.

Small businesses need capital in small doses. That’s a takeaway of the latest study published by the Federal Reserve that revealed 57% of employer firms (with less than 500 employees) that applied for financing in 2018, sought $100,000 or less. 20% sought less than $25,000.

56% of all financing applicants said they applied in order to expand their business or pursue a new opportunity while 44% said the funds would be used to meet operating expenses.

47% of employer firms that applied for credit received all of the financing they sought. 19% said they received less than half of what they needed and 22% said they didn’t get anything at all.

Unsurprisingly, those that received nothing were categorized as high credit risk. The Federal Reserve defined that category as having a FICO score less than 620 or a business credit score between 1 and 49.

SEC Finding Said that Prosper Misled Investors

April 22, 2019 From approximately July 2015 until May 2017, Prosper excluded certain non-performing loans from its calculation of annualized net returns that it reported to its investors, according to an SEC order released last Friday. The order found that Prosper reported overstated annualized net returns to more than 30,000 investors on individual account pages on Prosper’s website and in emails soliciting additional investments from investors.

From approximately July 2015 until May 2017, Prosper excluded certain non-performing loans from its calculation of annualized net returns that it reported to its investors, according to an SEC order released last Friday. The order found that Prosper reported overstated annualized net returns to more than 30,000 investors on individual account pages on Prosper’s website and in emails soliciting additional investments from investors.

As a result of the inflated numbered, which the SEC order says Prosper management was aware of, many investors decided to make additional investments based on the overstated annualized net returns. The SEC order said that Prosper failed to identify and correct the error that overstated its annualized net returns “despite Prosper’s knowledge that it no longer understood how annualized net returns were calculated and despite investor complaints about the calculation.”

“For almost two years, Prosper told tens of thousands of investors that their returns were higher than they actually were despite warning signs that should have alerted Prosper that it was miscalculating those returns,” said Daniel Michael, Chief of the SEC Enforcement Division’s Complex Financial Instruments Unit.

Prosper neither admitted nor denied the findings. The company did not refute the SEC order’s findings, including that it violated the antifraud provision contained in Section 17(a)(2) of the Securities Act of 1933. Prosper will pay a $3 million penalty for miscalculating and overstating annualized net returns to retail and other investors.

According to a 2017 Financial Times story, one Prosper investor wrote on the Lend Academy forum in 2017 that their returns were restated from about 14 percent to 7 percent.

“Shame on me for just assuming that I was getting a higher rate,” the investor wrote, “but shame on Prosper x 1000 for misleading investors.”

In a written statement to deBanked today, a Prosper representative characterized the miscalculation as an error only, not a scheme. She conveyed that when Prosper discovered the error in 2017, they notified investors who were impacted and changed the numbers so that they accurately reflected the investors’ returns.

“We’re pleased to have the SEC inquiry resolved and appreciate the SEC’s recognition of our cooperation as the agency looked into this matter,” read a statement provided by Prosper. “Since discovering and fixing this issue two years ago, we have put additional controls in place designed to detect and prevent similar errors in the future, and we are committed to providing transparent information on returns to our retail investors.”

Prosper’s CEO, David Kimball, was awarded “Executive of the Year” at this year’s LendIt Fintech conference earlier this month.

In 2018, the company originated $2.8 billion in loans, remaining flat compared to 2017. Prosper’s net revenue last year was $104 million, a decrease compared to $116 million in 2017. Founded in 2005 and headquartered in San Francisco, Prosper provides personal loans up to $40,000 and was one of the first peer to peer lenders.