Story Series: The Broker

IT’S A BROKER’S WORLD

August 31, 2016

From east to west, small businesses are getting funded. But how they’re found and who they work with depends on where they are. In the US, where brokers tend to have a love/hate relationship with the funding companies they work with, they are no doubt a driving force in the market. In other countries, they might not even exist, are just starting to bloom or they add balance to a mature market. Is the world built for brokers? deBanked traveled far and wide to find the answers.

Down under in Australia where American-based merchant cash advance and lending companies have expanded, the ISO (which stands for Independent Sales Office and is synonymous with broker) model has not really followed. David Goldin, CEO of Capify, an international company headquartered in New York, told deBanked that there’s very few ISOs in Australia.

He believes that’s because there’s next to no payment processing ISO market there, a foundation that was a major precursor in the US towards the development of ISOs reselling merchant cash advances and business loans.

He believes that’s because there’s next to no payment processing ISO market there, a foundation that was a major precursor in the US towards the development of ISOs reselling merchant cash advances and business loans.

Luke Schmille, President of CapRock Services, echoed same. The Dallas-based company founded Sprout Funding in Australia earlier this summer as part of a joint venture with Sydney-based family office Huntwick Holdings. “Direct marketing is the primary method [of acquiring deal flow],” he said. “The credit card processing space is controlled by several large banks, so you don’t see ISO efforts in the acquiring space either.”

Big bank dominance was only one reason why another country’s emerging alternative small business funding market developed slowly. In Hong Kong, non-bank alternatives like merchant cash advances faced legal uncertainty for a long time. For example, Global Merchant Funding (GMF), once the only merchant cash advance company in the Chinese special administrative region, had been relentlessly pursued for years by the Secretary for Justice for conducting business as a money lender without a license. GMF fought it. And won.

In May of this year, the legality of merchant cash advances ultimately prevailed after the highest court ruled the agreements were not loans. Emboldened, several companies have stepped up their marketing of the product. But whether they’re doing daily debit loans or split-processing merchant cash advances (both of which exist there), marketing tends to be directed at merchants, not a middle market of brokers.

Gabriel Chung of Hong Kong-based Advanced Express Capital said that there are a handful of large brokers typically comprised of former bankers, but the rest of the broker market is highly fragmented, mostly made up of individual freelancers.

Gabriel Chung of Hong Kong-based Advanced Express Capital said that there are a handful of large brokers typically comprised of former bankers, but the rest of the broker market is highly fragmented, mostly made up of individual freelancers.

Adrian Cook, the Founder and CEO of Hong Kong-based Asia Capital Advance, agreed that marketing is usually aimed at merchants directly but that it’s changing. “Since the market is still very new and MCA is only beginning to gain popularity, brokers on the market are only starting to recognize MCA,” he said. “There is a lot of room for the brokerage market to grow.”

In the UK, where Capify also operates, CEO David Goldin explained that the UK doesn’t have a lot of credit card processing ISOs so there wasn’t a major migration from that business to MCA like there was in the US. But that doesn’t mean there is no middleman market at all.

Paul Mildenstein, executive director of London-based Liberis, said that brokers are an important channel, but not as dominant as they are in the US. “Our brokers are usually members of the NACFB, an organisation in the UK that actively supports and provides operating principles to the furtherance of the commercial finance broker community,” he wrote. The National Association of Commercial Finance Brokers claims to have 1600 members, one among them is Liberis.

Paul Mildenstein, executive director of London-based Liberis, said that brokers are an important channel, but not as dominant as they are in the US. “Our brokers are usually members of the NACFB, an organisation in the UK that actively supports and provides operating principles to the furtherance of the commercial finance broker community,” he wrote. The National Association of Commercial Finance Brokers claims to have 1600 members, one among them is Liberis.

“Many clients want the support of an experienced professional who can discuss the financial options available to them in their specific circumstances,” said Liberis’ CEO, Rob Straathof. “Given relatively low awareness of the Business Cash Advance product in the UK, this means that brokers have a key role to play in educating potential customers on when this is the right option for them,” he added.

Straathof stressed a robust criteria for the brokers they work with and explained that brokers are their eyes and ears in the market. “The relationships we have with them are not transactional, but transformational for our business,” he said.

The NACFB was also praised by Alexander Littner, Managing Director of Chelmsford, Essex-based Boost Capital. The company, which is actually a subsidiary of Coral Springs, FL-based BFS Capital in the US, sees a balance between their use of brokers and their efforts to acquire customers directly.

“As the alternative finance market is still relatively new here in the UK these brokers are important for this independent advice, and to help educate the market and establish trust,” Littner said. “At Boost Capital we work very closely with brokers across the UK, they are a critical part of our growth and fundamental to our ongoing success.”

In the US, brokers play such a dominant role in customer acquisition that some MCA funding companies rely on them to source the entirety of their business. Back in February, Jordan Feinstein of NY-based Nulook Capital told deBanked, “We decided that the best way to grow is to build relationships to avoid the overhead, compliance, training and manpower that a sales team would require.” Nulook markets its broker-only approach as a strength.

Others take a more blended approach, like Justin Bakes, CEO of Forward Financing, for example. “While our priority is to self originate, it is essential to create and maintain partnerships in this business,” he said earlier this year.

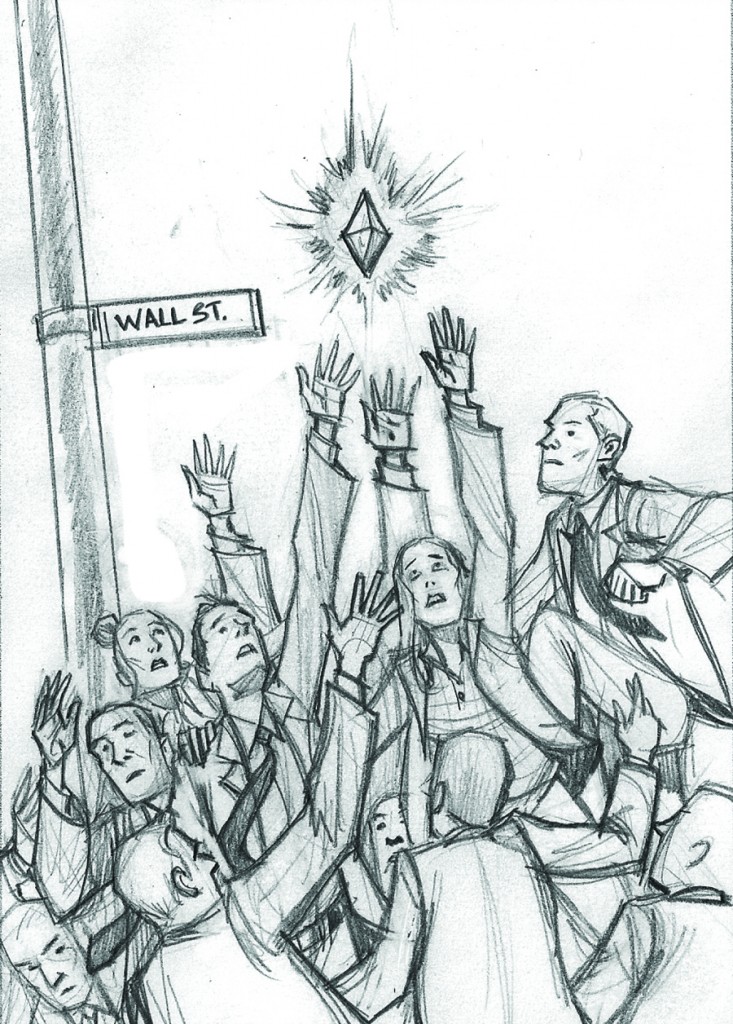

Notably, no such guiding authority like the UK’s NACFB exists for brokers in the US so it’s not easy to track exactly how many there are or how they operate, but their role in the industry cannot be understated. deBanked actually labeled 2015 The Year Of The Broker, when it published an article in its March/April 2015 issue that tried to capture the essence of the industry at the time. Tom McGovern, who was then a VP at Cypress Associates LLC, said of brokers, “They’re like the missionaries of the industry going out to untapped areas of the market.”

But preaching the gospel of alternative funding exists at different stages across the world. And Goldin, whose company Capify operates in four countries including the US, thinks that many middlemen here at home may not ultimately survive. In an interview, he predicted that the stronger ones over time will be acquired by funding companies and that direct marketing will only increase. “I think more and more companies are going to start building their own internal sales forces,” he said.

Other brokers are not convinced that acquisition costs will lead to the death of their businesses, especially if they’ve already found ways to reduce overhead costs. Several brokers have discreetly mentioned running operations from Costa Rica, Nicaragua or elsewhere as a way to keep things profitable. Still more, like Excel Capital Management based in Manhattan, have found that offering a suite of products allows them to monetize more customers. Chad Otar, a managing partner for Excel, said that they recently brokered a $4.9 million SBA loan. MCA is just one of their options these days. “As long as there’s small businesses, there’s always going to be opportunity,” he said.

In the US, the brokers have certainly seized it, but that’s because most funding companies offer big bucks and quick payment to those that are capable of sourcing customers. In other countries, compensation for services rendered might be the responsibility of the broker to arrange with the merchant since it may not be customary for funding providers to pay commissions. That would mean more work and more risk for the broker.

In the US, the brokers have certainly seized it, but that’s because most funding companies offer big bucks and quick payment to those that are capable of sourcing customers. In other countries, compensation for services rendered might be the responsibility of the broker to arrange with the merchant since it may not be customary for funding providers to pay commissions. That would mean more work and more risk for the broker.

Ironically, some brokers in the US will tap into both sides, earning a commission from the funder and charging a fee to the merchant for services rendered. And if the broker has payment processing roots, they can go a step further and earn merchant account residuals as well.

Brokers can’t exist without funding companies willing to support their endeavors, of course. While their prevalence around the world varies, most of the funding companies deBanked spoke to, appear eager to nurture the middleman’s role, so long as they act responsibly.

“Brokers in the UK are incredibly important as independent advisors to small businesses on the various sources of finance to suit their needs,” said Littner.

And as long as those customers, wherever they may be, are getting the value they want from a broker, that role, so long as it can continue to be done profitably, will likely have a place in the world for the foreseeable future.

Can an ISO “Excel” in 2016?

August 26, 2016

Don’t let anyone tell you that it’s too hard for a commercial finance broker to make a buck in exchange for honest work these days. One ISO in lower Manhattan is seeing more opportunity than ever before. Chad Otar, a managing partner of Excel Capital Management, sat down with deBanked to make his case for a bright future.

“As long as there’s small businesses, there’s always going to be opportunity,” Otar said. “Business owners are always going to need money.” Ironically, his own company that he cofounded in 2013 with hometown friend Nathan Abadi, was formed without any outside debt. Bootstrapped even to this day and even as they’re expanding, they’ve seen firsthand what other businesses around the country have to go through to get ahead.

“We’ve always believed in the products that we’ve sold,” said Otar, who brokers merchant cash advances, business loans, SBA loans, factoring products and more. They want every deal to help their clients whether it’s big or small, explaining further that even he himself has to feel comfortable with what the merchant wants. When asked about size, Otar said the largest SBA loan they got done was for $4.9 million.

But when questioned if more merchants were moving towards factoring and other traditional products, he explained that some merchants just don’t want to deal with the hassle of something that might be overly invasive or a process that might take a long time. They just want to get funded quickly, he said. And that’s where they come in.

Otar and Abadi’s optimism is not just anecdotal. The two partners, who previously renewed one year leases for their small office on Maiden Lane, saw enough runway to recently sign a five year lease for a 2,700 sq ft. office on Greenwich Street, staying within the bounds of the city’s financial district. Between full time employees and contractors, they currently house about fifteen people in their new office.

Though the partners live in Brooklyn, they, like many other companies in the industry, believe a Manhattan headquarters makes the most sense. “Everything is here,” Otar said. It’s easier to recruit new hires, he explained. And they indeed have immediate hiring plans now that they’ve got the space for it, both in sales and operationally.

Though the partners live in Brooklyn, they, like many other companies in the industry, believe a Manhattan headquarters makes the most sense. “Everything is here,” Otar said. It’s easier to recruit new hires, he explained. And they indeed have immediate hiring plans now that they’ve got the space for it, both in sales and operationally.

This new up-and-coming generation of business owners is very comfortable with the Internet and technology, Otar added, speeding up the process and allowing they and the funding partners they work with to do more deals together. One example offered was a small business owner who gave a guided tour of his establishment to an underwriter using FaceTime on his phone. Normally, the process would’ve been delayed by a few days because of the time it takes to hire a third party to perform a site inspection.

Some funding partners offer DocuSign so that merchants don’t even have to spend time printing and signing documents anymore, he said, qualifying that however by adding that while some merchants love it, others hate it and feel more comfortable doing things the old fashioned way. He acknowledged that was likely due to the generational gap that still exists.

When asked if the setbacks and gloom that had begun to envelop the consumer lending side of fintech, was also affecting the commercial side, Otar said he didn’t see it. Funders are still very aggressive with approvals and terms, he said. While paperwork required for approval is declining overall, he described one obstacle that he hadn’t really dealt with in previous years, UCC filings that are accidentally left active even when the agreements are satisfied in full.

Underwriters doing due diligence might interpret active UCCs to mean that outstanding obligations still exist. Absent a formal termination of the UCC, an underwriter may request that merchants provide documents from the secured party to support that a termination should’ve been filed. This in itself is not a burdensome task but Otar said he has seen merchants who have used alternative financing products continuously over the last eight years or so, who are then challenged to produce satisfaction letters from dozens of companies, some of whom the merchant may only vaguely remember.

But he is not discouraged when new challenges come up. “We’ve been constantly learning,” he said. And when asked what their secret to success has been up until this point, “It’s hard work and dedication,” he responded.

Meet the Source: How Jared Weitz and United Capital Source became one of the industry’s fastest growing shops

October 23, 2015Jared Weitz came from humble beginnings and nearly settled for a humble fate. But associates say an ordinary, uneventful life wouldn’t have suited him – he works too hard and figures things out too quickly.

Almost ten years ago Weitz, 33, was parking cars to earn money for community college. After finishing at St. Johns University, he almost made plumbing his career. But now he’s CEO of United Capital Source LLC, an alternative-finance brokerage with deal flow of between $9 million and $10 million a month and an annual growth rate of over 65 percent.

Business associates, former bosses and his small cadre of employees all seem to revere Weitz for his honesty and straightforwardness. They consider him a personal friend. They say he continues to grow as a businessman and as a human being while taking pleasure in helping others do the same.

Geographically, Weitz has the good fortune to know where he belongs – the city of New York is in his DNA. “Every time I fly back,” he said, “I’m so happy to land.”

His love affair with the city began in Brooklyn. He was born there and raised in a Brighton Beach apartment in the shadow of Coney Island. When he was 16, the family moved to Oceanside on Long Island.

As the second of six children, Weitz had to come up with the money for college on his own. “My older sister and I had to pay our way,” he said. “Everybody else, my dad was able to cover.” He started school at Nassau Community College, selling cell phones and parking cars at night.

But then came an abrupt change. Once Weitz saved enough money, he transferred to Tulane University in New Orleans to pursue a relationship with a woman who was finishing her studies there. He attended classes part-time, worked as the athletic director at the Jewish Community Center, tended bar in a Mexican restaurant and served summonses for a law firm.

But then came an abrupt change. Once Weitz saved enough money, he transferred to Tulane University in New Orleans to pursue a relationship with a woman who was finishing her studies there. He attended classes part-time, worked as the athletic director at the Jewish Community Center, tended bar in a Mexican restaurant and served summonses for a law firm.

The relationship with the woman fizzled, but Weitz made lasting friendships during his days down south. His old roommate in New Orleans, who now practices law in Atlanta, serves as counsel for United Capital Source.

When Weitz had been in New Orleans for two years, Hurricane Katrina struck. He evacuated to Houston, where he stayed in a Holiday Inn for two weeks before realizing he wouldn’t be able to return to southern Louisiana anytime soon. The magnitude of the devastation was just too great.

Shouldering the duffel bag of belongings he had managed to pack on his back during the evacuation, he returned to New York, enrolled in St. John’s University and began working in sales for Honda Financial Services and parking cars.

Weitz had started school expecting to become a teacher. He had grown up with younger siblings and liked leadership roles, which convinced him teaching would be a good fit.

Still, many of his college jobs had required him to sell. As a bartender, for example, he promoted drink specials. As an athletic director he convinced people to sign up for classes. “Everything that I took to naturally wound up being in the sales, marketing and finance arena,” Weitz observed.

When he was nearly finished at St. John’s, Weitz was parking a car for an acquaintance who offered him a job as a union plumber. Suddenly, he was making $27 an hour and had health benefits. “It was a big breather for me,” Weitz recalled.

He quit his three jobs and labored as a plumber from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. School started at 3:30 p.m. for him and stretched into the evening. But when he finished his degree, working as a teacher for $35,000 to $40,000 a year no longer seemed attractive.

Besides, his plumbing work didn’t center on toilets. On typical commercial plumbing jobs he did things like install air, medical and gas lines in hospitals. He was reading blueprints and bidding for jobs. A promotion to foreman didn’t seem that far off.

At about the same time, near the end of 2006, a friend, Mike Caronna, landed a job at Bizfi, formerly known as Merchant Cash and Capital (MCC), The company, which had just started and had only a few employees, was looking for underwriters.

As fate would have it, Weitz fell into a conversation with a fellow union plumber, one who had been on the job for 30 years. The older man reminded him that his wages would never climb much higher than they were right now. The veteran plumber then showed the younger man his hands, bent from decades of holding tools. “That got me thinking,” Weitz said.

He asked his friend Caronna to arrange a job interview at MCC. He got an offer and took a 90-day leave from his plumbing job to give the world of finance a try. “After about two weeks, I knew it was for me,” he said of the alternative-finance industry. It was by then the beginning of 2007.

Weitz excelled as an underwriter, and the company CEO, Stephen Sheinbaum, picked him and four others for a sales contest. Sheinbaum gave them some leads and turned them loose. Weitz won the competition but asked his boss to help him gain experience in business development and operations before taking on a sales position.

Sheinbaum was happy to comply. “He is one of the best and the brightest in the space,” he said of Weitz.

So, at age 25, Weitz found himself building a business development department by cultivating relationships with ISOs and persuading them to send business to MCC. “It was amazing,” he said of those days. “That was a big opportunity.”

Weitz learned the mechanics of the business. He found that the right ISO can originate good deals and a bad ISO can ruin deals. He learned the politics of when to talk, when to remain silent and when to let someone vent.

Then Weitz and a good friend at MCC, Anthony Giuliano – who’s now managing partner of Sure Payment Solutions – worked out how they could improve the MCC sales effort. They pitched Sheinbaum on the idea of having a second internal sale force, and that led to the birth of Next Level Funding (NLF), a division of MCC.

Weitz and Giuliano each owned 10 percent of NLF, and MCC owned 80 percent. “I’m 26, about to be 27, and I’m like, ‘You did it, Man,’” Weitz said as he looked back.

After about four months, NLF absorbed MCC’s original sales division. Next, Giuliano and another executive, Paul Giuffrida, decided to leave MCC. Weitz felt torn. He felt an allegiance to Giuliano and respected Giuliano’s knowledge of programming – a subject that was alien to him. Yet Sheinbaum had provided Weitz a series of opportunities.

Weitz stayed at MCC but felt he deserved to become chief sales officer. When that didn’t happen, he sold his shares back to the company at a dramatically reduced price to extricate himself from a non-compete clause and set off to start United Capital Source (UCS).

With a five-figure investment, Weitz and his then partner, started UCS in January of 2011 in a 250-square-foot office in Long Beach, L.I. Weitz invested about 90 percent of the money he had saved while working at MCC.

Jon Baum left NLF with Weitz and became the first UCS employee. Within a week or two, Danielle Rivelli, left NLF to join UCS, and Weitz put the remaining 10 percent of his savings into the business to meet the expanded payroll. Today, Baum and Rivelli are UCS sales managers.

Jon Baum left NLF with Weitz and became the first UCS employee. Within a week or two, Danielle Rivelli, left NLF to join UCS, and Weitz put the remaining 10 percent of his savings into the business to meet the expanded payroll. Today, Baum and Rivelli are UCS sales managers.

The first month UCS was open, it funded $240,000 in deals. “It just felt good to be on my own and start funding deals,” Weitz said. From the beginning of UCS, he won praise from funders for bringing them the right kind of deals with merchants who were likely to repay.

“He really has the pulse of the marketplace and what a lender is looking for,” said Todd Sherer, who handles business development for Entrepreneur Growth Capital. “He doesn’t waste time giving you transactions that don’t fit in your box.”

That’s because doing things right means a lot to Weitz. “He is one of the most straightforward, honest, high-integrity people I have met in the industry,” said Steven Mandis, adjunct associate professor at the Columbia University Business School and chairman of Kalamata Capital LLC.

He’s won the OnDeck seal of approval. “OnDeck has a rigorous and extensive background check process as part of our broker certification process,” said Paul Rosen, OnDeck’s chief sales officer. “Jared Weitz and United Capital have passed our screens and process and are currently active brokers for OnDeck.”

And with time, Weitz has learned patience. He was sometimes short with funders when he started his company but has matured into a pleasant person to deal with, said Heather Francis, CEO of Elevate Funding. “I’ve seen that growth with him,” she said.

All of those good qualities soon came together to help UCS succeed. Within four months of its launch, the company rented a 1,500-square-foot office in Garden City and hired two more people. Next came a 3,200-square-foot office in Rockville Centre and three more employees.

“The company was growing and gaining traction,” Weitz recalled. “I bought out my original partner.” Since then, Vincent Pappalardo has invested in UCS and become a minority partner.

Meanwhile, the lease was expiring on Long Island, and Weitz felt the time had come to move to Manhattan. That would enable the company to draw employees from throughout the region and not just Long Island.

“We decided to bite the bullet and pay the excess money to move to the city because we believed it would be better for the business,” Weitz said. He added two people and rented a 5,500-square-foot space near Penn Station in the Garment District in September of 2014.

Within three months of making the move to Manhattan, business doubled. “Being in a faster-paced environment caused the business to go through another growth phase,” he said. After nine months in the city, UCS is now taking over a whole 8,500-square-foot floor of the same building.

Within three months of making the move to Manhattan, business doubled. “Being in a faster-paced environment caused the business to go through another growth phase,” he said. After nine months in the city, UCS is now taking over a whole 8,500-square-foot floor of the same building.

UCS remains a small shop in terms of headcount with 21 people, but the company’s funding numbers equal the output of many brokerages five times its size. Twelve of the UCS employees work in sales, with the others engaged mainly in underwriting, operations and customer service.

Less than 2 percent of UCS’s funding volume comes from broker business. “We self-generate all of our business,” Weitz said, declining to elaborate too much on his company’s marketing efforts.

“My salespeople – bar none – are the best in the industry,” he claimed. “Much like the Navy has the SEALS and the Army has the Rangers, there are groups in the industry that can do triple or quadruple what other people do because that’s just the way they are.” His people fund an average of $750,000 per month per person in new business, while his renewals reps fund well into the 7-figure range per person.

UCS salespeople achieve their results because they have detailed knowledge of the industry, Weitz said. The staff’s understanding of alternative finance doesn’t end with sales but also includes underwriting and finance, he noted. “That’s what makes you a very good and knowledgeable sales rep,” he maintained.

His salespeople don’t just tell a client what he or she wants to hear. They take the time to understand the client’s financial situation. “They know how to read a profit and loss statement, a balance sheet and tax returns,” Weitz said.

ARE THE BEST IN THE INDUSTRY”

While 90% of Weitz’s sales team has a college degree, most of the salespeople have come from outside the industry, he said, noting that one was with Sleepy’s, the mattress company. Another was selling memberships at a gym, one worked for a credit card processing company, two were barbers and one had just graduated from college.

UCS doesn’t make double-digit commissions because the company isn’t over-charging merchants, Weitz maintained. The company does not obtain excess funding that a customer can’t afford or increase the factor rate to dangerous levels, he noted.

“You’re not really helping the merchant” by providing too much capital, Weitz asserted. “You’re sucking the blood out of him before he goes away. That’s not why I’m in business.”

A clean record will also prove beneficial when federal regulation comes to the industry, he said. Integrity in the workplace can also spill over into other parts of a person’s life, Weitz believes.

As UCS grew larger and Weitz grew older, he saw his employees rent their first apartments and then buy their first homes. He learned then that he had taken on more responsibility than was apparent to him at first.

As UCS grew larger and Weitz grew older, he saw his employees rent their first apartments and then buy their first homes. He learned then that he had taken on more responsibility than was apparent to him at first.

To accommodate the employees he added a human relations department and commissioned a company handbook. He’s also started marketing, finance, operations and other departments.

He’s lost only four employees because he pays them well, respects their time and doesn’t view their youth as a liability.

Meanwhile, talking daily to merchants and hearing about their heartaches and triumphs has humbled and matured Weitz. Seeing how the merchants’ choices panned out or fell short also shaped him and helped him grow up a little, he said.

Weitz has found time in his 70-hour workweek to meet his future bride. They’re planning to wed next year, and he plans to invite his entire staff. “It wouldn’t feel right without them,” he said.

Weitz has skipped the Ferrari, Rolls Royce and mansion because he didn’t feel he needed them. But even without those status symbols, it’s clear that Weitz has avoided settling for a humble fate.

As for what comes next, UCS is said to be developing an online marketplace to take their business to the next level, though Weitz declined to provide specific details about how it will work. “We’re on pace to do more than $100 million worth of deals a year,” Weitz said. “And as far as we’ve come, I feel like this is still just the beginning.”

From Lowes to Loans: Meet William Ramos

April 12, 2015Non-bank financing changed William Ramos’ life. Not as a borrower, but as a mover and shaker in the competitive world of financial deal-making. As an ambitious 20-year old, Ramos was working at both Lowes and ShopRite to try and put himself through Staten Island Community College. These were stepping stones, he told himself. He was dedicated to bettering himself, or more aptly to be the best at whatever he did.

Already on a path to success, he found himself growing impatient. The life of two jobs and school was a slow grind. Ramos wanted to do something big. He wasn’t sure what it would be, but he was confident that his attitude combined with his strong work ethic would eventually lead him to great success.

And so one day, he made a promise to himself to go out and find that big thing rather than wait for it to find him. It’s a bit of an American Cliché to say that his lucky break coincided with a sudden bout of adversity, but that’s exactly how it played out. Raised in the tough neighborhood of Brownsville in eastern Brooklyn, he didn’t have the connections to step right into the business world. Instead, Ramos had to start his search on the ground floor with millions of others on Craigslist.

His luck began with an interview for a job in telemarketing, a role that meant being connected to an autodialer nine hours a day as an opener. Undeterred by the challenge, Ramos had a feeling that this is where it would all begin. “I’ll do it,” he said.

There was only one problem, they didn’t want to hire him. The firm, which sold mostly financing products to small business owners, was very selective, even with cold callers. His interviewer at the time, who later became his boss, confirmed to me that he didn’t think Ramos was the right fit after they first met. But Ramos was determined to change his mind.

After calling the firm repeatedly over the next week to convince them that he was up to the task, they finally acquiesced. It didn’t mean he was in. It just meant it was time to put up or shut up. “They gave me a three-day trial period,” Ramos said.

After calling the firm repeatedly over the next week to convince them that he was up to the task, they finally acquiesced. It didn’t mean he was in. It just meant it was time to put up or shut up. “They gave me a three-day trial period,” Ramos said.

His former boss confirmed this relentless persistence.

39 working hours, 3,000 calls, and 3 days later, Ramos brought in two deals, one for $100,000 and another for $35,000. They both went through.

It was more than good enough to survive the trial and he was offered a job to work full time.

With a starting compensation of only $250 a week + commission, he still had a long way to go. “I would be the first one in and last one out,” Ramos shared with me. “I kept my head down and I wouldn’t leave my seat unless I needed to use the bathroom or eat. All I would do is make my calls.”

His former boss explained to me that Ramos had a knack for bringing in the firm’s larger deals even from the very beginning. He was too junior early on to be making a lot of money, but they were very focused on developing his skills. The firm saw his potential and was committed to nurturing him.

Within the first three months he managed to save $700 and he used it to buy a Mercedes-Benz C240 from a co-worker. After a life of taking the bus to work, Ramos had reached his first milestone of success.

While it was obvious that he still harbors pride in that first car, it sadly became all that stood in the way of homelessness. He had sacrificed everything for this job including college. Unfortunately there would be just one more thing to lose.

Adversity struck when a series of unfortunate events suddenly left him without a place to live. Ramos’ car was now both his ride and his home, though with the long hours he was putting in at the office, he might as well of lived at his desk. His boss took a special interest in his life and soon discovered just how much his young protégé was struggling.

“He was literally sleeping in his car,” his former boss told me. “I offered to let him sleep on my couch or at the very least let him stay in the office,” he added. Ramos took him up on the latter and began sleeping at the office. At the same time his commission percentage was bumped up, which sweetened the potential and only encouraged him to keep going.

Always looking for an edge, he sometimes pretended to be a customer himself. “I would call up lenders as a merchant to hear what pitches their sales teams were using,” he said. “I would then take that pitch, tweak it and make it my own.”

Always looking for an edge, he sometimes pretended to be a customer himself. “I would call up lenders as a merchant to hear what pitches their sales teams were using,” he said. “I would then take that pitch, tweak it and make it my own.”

Soon he was regularly closing more than $500,000 a month in deal flow and his financial situation and lifestyle began to improve significantly. A little more than a year later, Ramos had risen up to become a sales manager and was overseeing a team of five members.

Now some people in his shoes might’ve decided not to press their luck. He had taken a major gamble and it had paid off, so why do anything to jeopardize it?

But Ramos didn’t leave everything behind to settle for pretty good and a middle class lifestyle. After two years, he gave his boss and mentor some bad news.

“I’m going off on my own,” he explained. They parted on amicable terms and to this day still do business with each other. Ramos’ last commission check there was for $15,000, an amount he had never imagined back in his Lowes days.

In 2013 he founded Supreme Capital Group, a firm that primarily brokers merchant cash advances but will fund A paper deals on its own. With only two years in business, they are already on pace to generate more than $1.5 million in revenue over the next 12 months. He excitedly recalled a recent deal that generated $66,000 in commission. And that was just one deal!

He attributes part of his success to strong organizational skills. “I don’t think brokers realize how important keeping track of all their data is,” he said. He went on to explain that he can email the list of all his old leads and turn that into six to ten closed deals easily. He doesn’t have to work as much as he used to, but he still does.

With 10 callers working for him now, he’s not content with just being the boss. “I am still currently pounding the phones, doing email marketing, and sending out mailers,” he said. “We use the mailers to follow up with merchants, and we get a great response from it,” he added.

After working incredibly hard for several years, Ramos has at least found the time to play hard too. In the summer of 2014, he had made enough money to buy a white Maserati GranTurismo MC Sport Line, of which he shared several photos with me. He’s since upgraded to a 2013 Ferrari California in a color he described as Pepsi blue. And while that might be the kind of car some people would dream of sleeping in, Ramos has said those days are long over.

After working incredibly hard for several years, Ramos has at least found the time to play hard too. In the summer of 2014, he had made enough money to buy a white Maserati GranTurismo MC Sport Line, of which he shared several photos with me. He’s since upgraded to a 2013 Ferrari California in a color he described as Pepsi blue. And while that might be the kind of car some people would dream of sleeping in, Ramos has said those days are long over.

He just bought a house in Mesa, Arizona where his fiancée grew up and he plans to relocate his office there. “It’s already in the process of being built,” he said.

Ramos is now just 25 years old. He said he regrets not finishing school and he plans to go back. But he wouldn’t change everything that happened to him. He stressed more than once that asking questions is something he considers to be very important to success, especially in the business he’s in. “For all the newcomers in the industry, my advice would be to work hard and ask a lot of questions,” he said.

He was certain he had found the right opportunity almost from the beginning. “I knew that if I made those commissions the first week that I could make more,” he said.

It wasn’t easy.

William Ramos is the President of Staten Island, New York-based Supreme Capital Group.

Year of the Broker

April 4, 2015 Many of the newcomers are fleeing hard times in the mortgage or payday loan businesses. Others are abandoning jobs selling insurance, car warranties or search-engine optimization.

Many of the newcomers are fleeing hard times in the mortgage or payday loan businesses. Others are abandoning jobs selling insurance, car warranties or search-engine optimization.

“You have wandering souls trying to find their place in this industry, whether it be as a company or on their own,” said Amanda Kingsley, CEO of Sendto, a Florida-based company that assists new brokers.

Though exact counts appear difficult to obtain, Kingsley professed amazement at the volume of new entrants. “I’m swamped,” she said. “It’s crazy.”

Some of the new brokers discovered alternative financing in December, when OnDeck Capital’s initial public stock offering raised $200 million and valued the company at $1.3 billion. The Lending Club IPO that raised $1 billion the same month also raised public awareness of alternative loans.

Mesmerized with those whopping figures, salespeople from other businesses began committing themselves to a new career in alternative finance. In a business with virtually no barriers to entry, it’s easy to get started. To call themselves brokers, they just need a phone, someplace to sit and a list of leads they can buy online.

Virtually all of the entrants are pursuing dreams of lucrative paydays. Many even expect to make a fast buck with minimum effort.

If only it were that simple. Too often, the untutored new players are making mistakes simply because they don’t know any better, industry veterans maintained.

“A lot of people think you can just walk in and be successful,” said the sales manager of an established New York-based brokerage who asked for anonymity. “They don’t know what it takes to run a company. They don’t know what it takes to get a deal done.”

Worst of all – either unknowingly or with evil intent – new brokers are stacking deals. In other words, inexperienced salespeople pile second or third loans or advances on top of original positions. It’s an approach that clearly violates the industry’s standards, observers agreed.

In fact, virtually all contracts for a first loan or advance prohibit the merchant from taking on another similar obligation, noted Paul Rianda, an Irvine, Calif.-based attorney who specializes in payments and financing.

“I can’t remember one agreement I’ve seen that didn’t have that provision in it,” Rianda said.

Violating that stipulation could provide grounds for a lawsuit, and litigation is underway, according to David Goldin, president and CEO of New York-based AmeriMerchant and president of the North American Merchant Advance Association (NAMAA).

Bigger funders would sue smaller funders because the latter appear more likely to take on riskier, more problematic multiple-position deals, said Jared Weitz, CEO at United Capital Source LLC, a New York-based broker.

Plaintiffs have a case to make because stacking harms the broker and funder of the first position by increasing the risk that the merchant won’t meet the resulting financial obligations, Weitz said. “The guys going out 18 and 24 months to make this a more bankable product are being hurt by the people coming in and stacking those three-month high-rate loans,” he noted.

Deducting fees for more than one advance also impedes cash flow, adding another risk factor, Weitz said.

To further complicate matters, the company offering the second or even third deal sometimes moves the merchant’s transaction services to another processor, Rianda said. That forces the firms that made the first advance to approach the new processor to stake a claim to card receipts, he noted.

So the companies with the original deal suffer from the effects of stacking, but the practice’s shortcomings will haunt the stackers, too, observers maintained.

“It’s not a model that’s going to allow them to succeed,” a broker who asked to remain anonymous said of stackers’ long-term prospects.

Many hardly give a thought to staying power, according to Weitz. “A lot of people entering this space think it’s about fast money and not longevity,” he said.

Longevity requires that brokers build relationships with merchants, a process stacking undermines because too much credit can drive merchants out of business or merely prop up merchants already doomed to fail, sources said.

Yet stacking has become so widespread that it constitutes a business plan for some brokerage shops, said a broker who asked that his name and company not appear in the article.

It can begin when brokers buy lists of Uniform Commercial Code filings to find out what merchants have already taken out term loans or advances, said Zach Ramirez, vice president of sales and operations at Orange, Calif.- based Core Financial Inc.

The brokers then contact those merchants, many of whom are already over-extended financially, to offer additional credit or advances, Ramirez said.

Inexperienced brokers often resort to stacking because they don’t know how to generate leads that can bring alternative lending vehicles to merchants who weren’t aware of them.

Referrals from accountants or other business owners who deal with merchants can provide some of those greenfield prospects, Ramirez noted.

And leads aren’t the only area of cluelessness among newcomers, a broker who requested anonymity maintained.

And leads aren’t the only area of cluelessness among newcomers, a broker who requested anonymity maintained.

“They don’t know why a bank declines a deal or approves a deal,” he said. “They don’t know what’s the basis for a good deal.”

To teach new brokers those basics of alternative business financing, the industry should establish standard policies and technology, according to Kingsley.

A credential, perhaps something similar to the Certified Payments Professional designation created by the Electronic Transactions Association, sources said. To earn the credential, candidates would pass an exam to show they’ve mastered the basics of the business, they proposed.

NAMAA is considering such a credential, said Goldin, the trade group’s president. It’s the kind of self-regulation that could forestall federal oversight, industry sources agreed.

But that might not matter, according to Tom McGovern, a vice president at Cypress Associates LLC, a New York-based advisory firm that raises capital for alternative lenders and merchant cash advance companies.

After all, McGovern noted, Barney Frank, former Democratic U.S. representative from Massachusetts and co-author of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, has gone on record as saying that piece of legislation focuses on consumers and does not govern business-to-business dealings like loans or advances to merchants.

That lack of regulation over B2B deals seems likely to continue, “especially in the world we’re in now with a Republican Congress,” said a broker who asked to remain nameless.

However, some members of the industry would welcome federal regulation as a way of barring incompetent or unscrupulous brokers. An agency patterned after the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, know as FINRA, could do the job, suggested a broker who requested anonymity.

Whether a government regulator or an industry- supported association should police the market, problems could remain stubbornly in place, some said.

Many doubt an association could build the consensus required for united action on some issues – stacking in particular.

For one thing, cleaning up the business could reduce profits for brokerages that profit from stacking, noted a broker who asked that his name not appear in the article.

“Everybody wants to make money,” he said. “Everybody’s out for themselves.”

Another barrier to agreement arises because some brokerages fear cooperation could expose their trade secrets, said Sendto’s Kingsley.

Moreover, unscrupulous brokers want to keep their employees uninformed of the industry’s potential for big profits, Kingsley said. That way they suppress compensation for an underclass of prequalifiers who work the early stages of deals, she noted.

Prequalifiers earn from $150 to $500 a week, depending upon the location, and don’t qualify for benefits like health insurance, Kingsley said. Once they realize what a tiny portion of the profits they’re receiving, brokers terminate the prequalifiers and many go on to become brokers themselves, she observed.

Closers who take over from prequalifiers to wrap up the sale can earn up to 50% or occasionally even 60% of a brokerage house’s commission – if the closer originates the deal and sees it through to completion unassisted, Kingsley said.

Eventually, closers realize they could keep all of the commission if they strike out on their own and become brokers, she noted.

In a way, the progression from prequalifier to broker or closer represents a market correction. And many seasoned industry participants believe market forces will also work out other problems the influx of new brokers is causing.

A large number of the new brokers simply won’t last long because they don’t understand the industry, they’re stacking deals and they’re signing up merchants that won’t stay in business.

Meanwhile, funders are beginning to perform background checks on brokers to make sure they’re dealing with reputable people, sources said.

Some funders protect themselves by simply declining to do business with new brokers, according to observers.

And many new brokers are learning the industry with the help of experienced brokerages that act as mentors and conduits and call themselves super brokers, super ISOs, broker consultants or syndicators.

“So what I’m saying is, ‘Guys, let’s not compete. Let’s grow parallel together,’ ” Weitz said of United Capital Source’s relationships with new brokers. The company began working with new brokers in October 2014.

In such relationships new brokers get advice from the more seasoned brokers. The older brokers can also provide the newcomers with services that include accounting, marketing and reporting, he said.

New brokers can also benefit from the customer relationship management platform that United Capital Source developed, Weitz said.

The new brokers also capitalize on the older brokers’ relationships with funders. Established brokers have earned better rates and terms because of reputation and volume, Weitz noted. Companies like his also know which lenders work more quickly and thus capture more deals, he added.

Older brokers can also steer new brokers away from newer funders that offer shorter terms and demand higher rates, Weitz said. Of the 30 to 40 companies that call themselves funders, only eight or 10 deserve the name, he contended.

The less-respectable funders place only a small amount of money in a few deals, he said.

Newer brokers become aware of their need for help from more experienced brokers when they see how many sales they’re failing to close, Weitz said.

The new brokers also come to realize that the puzzle of running a brokerage office has a lot more pieces than they may have thought, said Kingsley.

The new brokers also come to realize that the puzzle of running a brokerage office has a lot more pieces than they may have thought, said Kingsley.

The percentage of the commission that the older broker charges can vary, according to Weitz.

“If someone needs a lot of hand holding and a lot more resources, they would get a different structure,” he said.

While Weitz said his company plans to acquire only about 10% of its volume through new brokers, Sendto specializes in helping newcomers. Sendto’s Kingsley described the company as “a turnkey solution that provides training and placement of deals. It’s for new brokers or sales offices that do not have what they need to be part of this industry.”

There’s room for entrants because not all merchants know about alternative business financing, said McGovern.

The market can even seem like it doesn’t have enough brokers in the estimation of experienced players skillful enough to find the many merchants who haven’t been introduced to the industry, said Ramirez of Core Financial.

And the big banks don’t really want the business because the deals aren’t big enough to interest them, McGovern said.

But the potential profits look promising to outsiders disillusioned with sales jobs in other industries.

Some experienced brokers even prefer to hire salespeople from outside the alternative financing industry, noted Kingsley. That way, they avoid employees who have picked up bad habits at other brokerage houses, she said.

Long-time members of the industry sometimes enjoy belittling new entrants who can seem clueless about the business they’re trying to master, noted Ramirez of Core Financial. But he recalled the time not so long ago that he himself had a lot to learn.

And regardless of how unsophisticated they may seem, new players have a role, McGovern said.

“They are performing a service,” he maintained. “They’re like the missionaries of the industry going out to untapped areas of the market – of which there are many – and drumming up business.”

To Kingsley, brokers in general – old and new – are beginning to earn the respect they deserve.

“A lot of people are afraid of the word ‘broker,’ ” she said. “I feel that 2015 is the year of the broker, and people should embrace what a broker can actually do. It’s a great thing.”

Should I Start an ISO With Only $2,000?

January 12, 2015A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…

It is a period of civil war. Rebel sales reps, striking from a hidden ISO, have won their first victory against the evil Galactic Funder.

During the battle, Rebel spies managed to steal secret formulas to the Funder’s ultimate weapon, the UNDERWRITING ALGORITHM, an advanced code with enough power to destroy an entire industry.

Pursued by the Funder’s sinister sales agents, our hero races home with her flash drive, custodian of the stolen formulas that can save her merchants and restore freedom to the industry…

Breaking away to start your own ISO or brokerage in this industry used to be a rite of passage. You started somewhere, learned the ropes, then went off on your own like a Jedi Master.

The stories of reps and underwriters of years past who left their jobs to start their own ISOs are a bit nostalgic. Young twenty-somethings defying authority to plant their own flags in an industry they felt offered unlimited potential. For some, going solo was a rude awakening, a healthy taste of the real world, where you needed to be able to do more than just close the leads you’re given. But for others? Well, today they are the owners or managers of companies worth millions, tens of millions, or hundreds of millions of dollars.

Empires were built not that long ago and they certainly were not in a galaxy far, far away. But today the prospects are much bleaker. The industry has matured and certain channels are saturated. Merchant cash advance and non-bank business lending are no longer part of a young unexplored universe.

So to those that have asked me whether or not it makes sense to start an ISO in 2015, I’d have to say in many cases it does not. It’s a little late in the game. Below is one of the most popular questions posed to me over the last six months:

Q: I’m thinking about starting my own ISO. I have about $2,000 to $5,000 to spend on leads. Do you think I can do it and where should I buy the best leads from?

Q: I’m thinking about starting my own ISO. I have about $2,000 to $5,000 to spend on leads. Do you think I can do it and where should I buy the best leads from?

A: There’s a few things to address here. If you are working out of your house and your rent/mortgage is already taken care of without you having to pay yourself from your new ISO, you may be able to turn a profit starting with something this small. The first problem though is that if you’re not absolutely positive where to get excellent leads, you’re going to spend a lot of money on experimenting with multiple sources. $2,000 might be the cost of an experiment with one lead provider. In other cases, it might be $5,000. Your entire budget could get wiped out in an experiment with just one source.

There may be no barriers to entry in this business, but $2,000 to $5,000 is entirely too little to give yourself a real chance to get off the ground. Direct mail takes a lot of trial and error and thousands of dollars. Google/Bing advertising takes even more trial and error and tens of thousands of dollars before you can get really meaningful results.

And if you’re going to put all your eggs in the UCC marketing basket because of budget, it’s going to be a tough climb uphill.

The companies that do actually have the best leads don’t need a $2,000 startup ISO to sell them to. A big ISO or funder is probably already paying double the price they’re worth.

So how do you stand a chance? You should realize that the odds are you won’t.

And if you need to allocate part of that 2-5k to pay for an office and get set up like a business, you might not have anything left for marketing at all. That’s a horrible place to be!

Lastly, I have seen many ISOs try to become a broker’s broker in order to acquire deals. That means trying to close ISOs to send you deals for you to forward on to a funder as a middleman where you will get a cut if the deal closes. It’s a hustle, and if you can swing this, great, but it’s not exactly a sustainable model especially if the ISO realizes they can go direct to the funder themselves. If you can’t acquire merchants on your own (and deals you stole from the last place you worked at don’t count as acquiring on your own), then you probably shouldn’t be in the ISO business at all.

If you’re going to start an ISO in 2015, I suggest having a minimum $25,000 (50k to be safe) in marketing to start off. And if you don’t know what you’re doing, well then may the force be with you.