PPP

When The Music Stopped: How The Pandemic Threatened the History and Culture of Austin, Texas

November 15, 2020

In April of this year, Threadgill’s – a legendary Austin music venue and beer joint that, in the 1960s, famously launched the career of blues singer Janis Joplin — turned off the lights and pulled the plug on its sound stage.

A converted gasoline station, Threadgill’s had been a rollicking music scene since 1933 when musician and bootlegger Kenneth Threadgill secured the first liquor license in Texas after Prohibition. His juke box was crammed with Jimmie Rodgers songs and Threadgill himself famously sang and yodeled Rodgers’ tunes.

For generations of students at the University of Texas, Threadgill’s was a rite of passage.

For generations of students at the University of Texas, Threadgill’s was a rite of passage.

“The first time I went to Threadgill’s was in the fall of 1968, when I was a freshman at UT,” recalls Perry Raybuck, a songwriter-folksinger and retired government worker who, as a member of the Southwest Regional Folk Alliance, played the stage in 2018. “It was the beginning of an education for me,” he adds. “I had been a Beatles and rock n’ roll kid and it opened me up to different music styles. I became a convert.”

In 1981, Threadgill’s was taken over by another acclaimed club owner, Eddie Wilson, who previously had been the proprietor of the Armadillo, a fabled music venue. Wilson began to actually pay musicians – Threadgill had compensated them mainly with free cold beer – and installed a circular stage.

It was Threadgill’s and an assortment of funky clubs and stages with names like the Soap Creek Saloon and Liberty Lunch helped put Austin on the map as “The Live Music Capital of the World.” The city remains home to the widely acclaimed television program “Austin City Limits” on PBS and the internationally renowned South by Southwest festival, which was canceled this year amid fears of a “superspread” of the coronavirus.

It was Threadgill’s and an assortment of funky clubs and stages with names like the Soap Creek Saloon and Liberty Lunch helped put Austin on the map as “The Live Music Capital of the World.” The city remains home to the widely acclaimed television program “Austin City Limits” on PBS and the internationally renowned South by Southwest festival, which was canceled this year amid fears of a “superspread” of the coronavirus.

“Live music,” says Laura Huffman, chief executive at the Austin Chamber of Commerce, “is why people come here. It is a central component of Austin’s cultural and economic life.”

Omar Lozano, director of music marketing for Visit Austin, the city’s main tourism organization, says: “We have close to 250 places in the greater Austin region where you can hear live-music, although it’s closer to 50-70 on any given night. During South by Southwest, no stone is left unturned — everything becomes a stage: parking garages, grocery stores, housing co-ops. There are also four or five stages at the Airport, which helps liven up the mood.”

But that identity is being put to the test. So far this year, Austin has lost a raft of live music venues. Among those joining Threadgill’s in honky-tonk heaven since the pandemic struck are Barracuda, Plush, Scratchhouse, Shady Grove, and Botticelli, all of which provided niche audiences to both established musicians and up-and-coming acts.

The roller-coaster ride of government mandated shutdowns followed by a limited re-opening in the spring and another shutdown since July fourth is making life miserable and untenable for both club owners and already hardpressed musicians and artists, says Marcia Ball, a piano player and blues singer.

Ball, who was named by the Texas Legislature as “2018 Texas State Musician” and whose musical style was once described by the Boston Globe as “mixing Louisiana swamp rock and smoldering Texas blues,” told deBanked: “There was already a limited amount of opportunity for musicians to perform and monetize their work in Austin, so it has always been necessary to travel to make a living. But we still depend on a thriving local scene, and we’re losing that when key venues like Threadgill’s disappear.”

Adds Graham Williams, a prominent Texas promoter of touring bands: “These venues and bars are vital to the music ecosystem. Local bands and cover bands need hangouts, even if people are not buying tickets. They’re places to play every night of week.”

While unheralded outside the Austin scene, the local music joints were often a port-of-call for out-of-town promoters and nightclub owners checking out Austin talent – “most notably Barracuda (which) had super-popular acts and was like a hipster garage venue,” says promoter Williams. “A lot of touring bands played there on their way up.”

A July study by the Hobby School of Public Affairs at the University of Houston found that the city’s live music industry is in desperate straits. Sixty-two percent of live music spots and 55% of the bar-and-restaurant businesses reported to researchers that that they can endure for no more than four months, making them the most vulnerable of 16 industries surveyed.

And the situation has become “even more ominous” since the report was published, explains Mark P. Jones, a political scientist at Rice University in Houston and a lead researcher on the Hobby study. “That survey finished polling two hours before all bars and restaurants closed back down,” he says. “Everything people were saying was when bars were at 50% capacity. That’s a best-case scenario.”

Austin’s experience amid the Covid-19 pandemic mirrors what is occurring nationwide as bars, nightclubs and music halls in myriad cities and towns experience similar trauma. In Seattle, Steven Severin is co-owner of three nightclubs – Neumos, Barboza and recently opened Life on Mars – all in trendy Capitol Hill, the hub of the city’s club and live-music scene. He reports that he is barely holding on thanks to some help from the city and a sympathetic landlord who is “a big music advocate.”

Austin’s experience amid the Covid-19 pandemic mirrors what is occurring nationwide as bars, nightclubs and music halls in myriad cities and towns experience similar trauma. In Seattle, Steven Severin is co-owner of three nightclubs – Neumos, Barboza and recently opened Life on Mars – all in trendy Capitol Hill, the hub of the city’s club and live-music scene. He reports that he is barely holding on thanks to some help from the city and a sympathetic landlord who is “a big music advocate.”

“He knocked down the rent a little bit,” Severin says of his landlord, but the situation is dire. “We just had a fifth venue, Re bar, close at the end of August,” he says. “It was a punch in the gut. This could be me.”

The Bitter End in Greenwich Village is also keeping its head above water despite not opening its doors since March. The nightclub has a storied past: owner Paul Rizzo recounts that it is where pop singer Neil Diamond got his start and where “everyone from Curtis Mayfield to Randy Newman” has performed since its opening in 1961. But the club is silent now since the pandemic overwhelmed the city’s hospitals and made New York the epicenter of sickness and suffering during the spring. So far the club is getting help from a landlord’s forbearance and loyal musicians.

Peter Yarrow (the “Peter” in the bygone trio Peter, Paul and Mary), donated a streamed concert to patrons who contributed to a fundraiser that raised more than $50,000. And grateful local musicians also put on a benefit directing people to a Go Fund Me page on the Internet that raised another $16,000. “We’re a major venue for local musicians,” Rizzo says. “We should pull through.”

It’s in their self-interest for artists to do whatever they can to keep the doors open at a club like The Bitter End. “These days because of the last two decades of declining record sales — live music is the bread and butter of a musician’s income,” says journalist Edna Gundersen, a recently retired, 28-year-veteran of USA Today. “That’s true whether it’s a local entertainer or an international superstar.” (Gundersen earned the reputation as Bob Dylan’s favorite journalist; it was she who scored his only interview after he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2018, publishing his eccentric musings in the The Telegraph of London and breaking the news that he would indeed accept the prize.)

“Touring has been crushed,” Gundersen adds, “and festivals have been canceled. So people doing the circuit and clubs are gone for all intents and purposes. Streaming — while initially up — is down because people aren’t listening to music in the gym or in their cars. Physical record sales are also down because people aren’t going to stores. All of this is just killing musicians.”

The Paycheck Protection Program, the multi-billion, multi-tranche aid package for small business which Congress authorized as part of the CARES Act in March, has provided some funding for the live-music and entertainment industry. But because of the PPP’s requirements that only 40% of the funds can be spent on rent, mortgage and utilities, which are major expenses for nightclubs and music venues, the program has largely been a disappointment.

The Paycheck Protection Program, the multi-billion, multi-tranche aid package for small business which Congress authorized as part of the CARES Act in March, has provided some funding for the live-music and entertainment industry. But because of the PPP’s requirements that only 40% of the funds can be spent on rent, mortgage and utilities, which are major expenses for nightclubs and music venues, the program has largely been a disappointment.

Hoping to win attention and assistance for their plight from the federal government — “We’re the first to close and the last to reopen,” Severin says — live-music entrepreneurs like himself and Rizzo and more than 2,800 club-owners and promoters across the country have banded together to form the National Independent Venue Association.

Their membership includes independent proprietors (no corporate members allowed) of saloons, cabarets and concert halls as well as theaters, opera houses and auditoriums from every state plus the District of Columbia. To help plead their case with Congress, the organization hired powerhouse law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, the largest Washington, D.C. lobbying firm by revenue.

NIVA also blanketed Congressional offices with two million letters, e mails and correspondence generated from hordes of fans and performers. Among the many scriveners are a slew of boldface names: Mavis Staples, Lady Gaga, Willie Nelson, Billy Joel, Earth Wind & Fire, and Leon Bridges. Comedians Jerry Seinfeld, Jay Leno and Jeff Foxworthy have also penned notes to lawmakers championing NIVA’s cause.

Their message: without federal funding, 90% of independent stages will go under over the next few months. “The heartbreak of watching venues close is that once a building is boarded up, it’s not going to be a music venue any more,” warns Audrey Fix Schaefer, communications director at NIVA. “They operate on thin business margins to begin with and they’re too hard to develop.” For touring acts, each city stage is “an integral part of the music ecosystem,” Schaefer explains. “When artists finally do get back on the tour bus, they might have to skip the next five cities and go on to the sixth.”

Thanks to the bi-partisan efforts of Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Senator John Cornyn (R-Texas), NIVA’s campaign has gotten traction. The unlikely couple have teamed up to author a rescue bill, known as the Save Our Stages Act. If enacted, it would establish a $10 billion grant program for live venue operators, promoters, producers, and talent representatives.

Thanks to the bi-partisan efforts of Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Senator John Cornyn (R-Texas), NIVA’s campaign has gotten traction. The unlikely couple have teamed up to author a rescue bill, known as the Save Our Stages Act. If enacted, it would establish a $10 billion grant program for live venue operators, promoters, producers, and talent representatives.

The legislation would provide grants up to $12 million for live entertainment venues to defray most business expenses incurred since March, including payroll and employees’ health insurance, rent, utilities, mortgage, personal protection equipment, and payments to independent contractors.

NIVA’s chief argument for the legislation is coldly economic rather than sentimentally cultural. The organization cites a 2008 study by the University of Chicago that spending by music patrons produces a “multiplier effect” for the broader economy. For every dollar spent by a concert-goer at a live performance, the Chicago study determined, $12 in downstream economic activity occurs.

Explains Scott Plusquellec, nightlife business advocate for the City of Seattle: “You buy a ticket to a show and the direct economic impact of that purchase is that it pays the artist, bartender and the club itself as well as the band, advertisers, and promoters. The indirect economic impact,” he adds, “is that after you bought the ticket, you went to a barber shop or a hair salon to look good that night. You might also have dinner, go to a bar for a drink and tip the bartender. That’s the whole the idea of a ‘multiplier.’”

In Austin, that economic logic is an article of faith with city burghers, asserts Lozano of Visit Austin, who reports that live music in the capital city is roughly a $2 billion industry. To promote live music, the tourism bureau sponsors such endeavors as “Hire an Austin Musician.” That program, Lozano says, “sends musicians around the U.S. to represent us during marketing season.” In another promotional campaign, Visit Austin arranged for singer-songwriter Julian Acosta to play a gig at travel agents’ offices in London when Norwegian Air inaugurated direct flights between London and Austin in 2018. “The U.K. is one of our best markets,” he reports.

Even so, efforts by the business community and the City of Austin have failed to stanch much of the industry’s bleeding. According to its website, the city has disbursed $23.7 million in loans and grants to small businesses and individuals, but slightly less than $1 million of that has gone to live-music and performance venues, entertainment and nightlife, and live-music production and studios.

In late September, The city of Austin’s Economic Development Department released a slide show breaking down how the $981,842 in industry grants and loans – of which $484,776 was provided by the federal government under the CARES Act – were awarded. Most top recipients appeared to be well known nightclubs and entertainment venues downtown or close to the city’s inner core.

In late September, The city of Austin’s Economic Development Department released a slide show breaking down how the $981,842 in industry grants and loans – of which $484,776 was provided by the federal government under the CARES Act – were awarded. Most top recipients appeared to be well known nightclubs and entertainment venues downtown or close to the city’s inner core.

The Continental Club on South Congress – a key fixture in the hip “SoCo” strip just over the Colorado River from downtown – appeared to do best. It picked up $79,919 from two programs: $40,000 in the CARES-backed small business grants program, and $34,919 from the city’s Creative Space Disaster Relief Program. Other clubs receiving $40,000 in the small business grants program included Stubbs, The Belmont, Cheer Up Charlies and the White Horse. (For a full list go to: http://www.austintexas.gov/edims/document.cfm?id=347299)

Joe Ables, owner of the Saxon Pub, a major Austin venue for jazz – blues singer Ball hailed it as one of several important Austin clubs “that sustains creative endeavor, especially for songwriters” – was vexed that his grant application was denied by the city “with no explanation.” Ables also voiced dissatisfaction that the city paid the Better Business Bureau a 5% administration fee to handle $1.14 million in relief funds, including determining which applicants were approved. “What would they know about live music,” he says.

Even for clubs that received city largesse, it hasn’t been nearly enough to sustain them. The North Door, which got $15,240, closed for good on September 11 (an ominous day — the anniversary of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.)

Meanwhile, enough clubs and venues were left out in the cold that club owner Stephen Sternschein could tell deBanked just before the slide show was released: “I’ve heard talk of a $21 million grant program but most people I know haven’t seen a dollar of that.”

Sternschein is managing partner of Heard Presents, an independent promoter and operator of a triad of downtown clubs that includes the spacious Empire Garage, which features hip hop and urban jazz, and has space for 1000 music-goers. A member of NIVA, Sternschein describes efforts by both the state and local governments as “woefully inadequate.” Says he: “People are looking to the federal government for answers.”

The diminution of places for musicians to ply their trade is a double edged sword. If Austin loses its luster as a hot music town, it puts the city’s overall economy in jeopardy. Explains Jones, the Rice political scientist: “The difficulty for Austin is that it could lose its comparative advantage. Unlike restaurants, movie theaters or sports events, which people can find just as easily in other cities, the Austin music scene draws capital and revenue from across the country.

The diminution of places for musicians to ply their trade is a double edged sword. If Austin loses its luster as a hot music town, it puts the city’s overall economy in jeopardy. Explains Jones, the Rice political scientist: “The difficulty for Austin is that it could lose its comparative advantage. Unlike restaurants, movie theaters or sports events, which people can find just as easily in other cities, the Austin music scene draws capital and revenue from across the country.

“You can go out to dinner in Waco,” he observes, referring to the mid sized Texas city between Austin and Dallas best known as home to Baylor University and its “Bears” football team, fervent Baptist religiosity, and unremarkable night life. “Music brings in revenue to Austin and to Texas that wouldn’t otherwise come here.”

In addition, Jones says, the large presence of “artists, creative types, and freelancers” helps make Austin a strong selling point for “brain industries” to attract talent from the East and West Coasts. “It supports the technology industry by making it easier to recruit employees to live there,” he says. “Austin is an alternative to Silicon Valley. People who are progressive might be hesitant to come to conservative, red-state Texas from California but they’ll come to Austin because it’s culturally cool.”

Austin, which embraces the slogan “Keep Austin Weird,” is on the verge of becoming just like every place else in Texas. Should it relinquish its flavor and charm, it could discourage many of the assorted business groups and professionals from keeping Austin on their dance card as a popular destination for meetings, conferences and get-away trips.

Howard Freidman, managing director at Bluechip Jets, a broker of private luxury aircraft, had an earlier career as a technology industry executive. Partly drawn by his previous experiences with the city, Freidman moved to Austin earlier this year. “It had the same coolness and weirdness of New Orleans — but also with the professionalism of a tech city,” he says.

“Whenever we’d come here,” Freidman adds, “the music was always integral to the Austin scene. Even when you’d go to private parties you’d end up downtown at the club scene on Sixth Street. Austin was always a place everybody liked going to.”But as Austin has steadily been morphing into more of a high-technology center than a live-music town, it’s experiencing a silent exodus of musicians and artists who are being gentrified out of their apartments and Craftsman duplexes. Displacing them are software engineers, website designers and the like, their sleek BMWs and black, tinted-glass SUVs glistening in the parking lots of steel-and-glass corporate centers.

“Whenever we’d come here,” Freidman adds, “the music was always integral to the Austin scene. Even when you’d go to private parties you’d end up downtown at the club scene on Sixth Street. Austin was always a place everybody liked going to.”But as Austin has steadily been morphing into more of a high-technology center than a live-music town, it’s experiencing a silent exodus of musicians and artists who are being gentrified out of their apartments and Craftsman duplexes. Displacing them are software engineers, website designers and the like, their sleek BMWs and black, tinted-glass SUVs glistening in the parking lots of steel-and-glass corporate centers.

Many of the technology firms – including such needy companies as Samsung, Intel, Rackspace, Facebook, and Apple – have each received tax breaks, grants and subsidies worth tens of millions of dollars from a variety of local jurisdictions. Not only have the city of Austin and Travis Country been beneficent, but adjacent county governments and the state of Texas have provided abundant support. A 2014 study by the Workers Defense Project, in collaboration with UT’s Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, reported that the state of Texas showers big business with $1.9 billion annually in state benefits. Most recently, officials with Travis County and a local school district granted Tesla more than $60 million in tax rebates to build a massive “gigafactory” southeast of town near Austin-Bergstrom International Airport.

To house the burgeoning cohort of “knowledge workers,” there are condominium conversions, tear-downs, high-rises and other forms of frenetic real estate development which, in their train, bring higher property taxes, steeper rents, and unaffordable housing.

Add in some of the country’s most snarled traffic, dirtier air, and a growing homeless population, and members of the artistic community are increasingly decamping for smaller satellite towns like Lockhart and San Marcos. Others in the diaspora are abandoning Texas altogether for more hospitable locales like Fayetteville Ark., Asheville, N.C., or Olympia, Wash. “Whatever made anybody think this would be a better town with a million people,” laments blues singer Ball. “This was a perfect town with 350,000. Now we’ve got Silicon Hills, Barton Springs are cloudy, and drinking water’s going to be scarce. Why is this supposed to be better?”

Add in some of the country’s most snarled traffic, dirtier air, and a growing homeless population, and members of the artistic community are increasingly decamping for smaller satellite towns like Lockhart and San Marcos. Others in the diaspora are abandoning Texas altogether for more hospitable locales like Fayetteville Ark., Asheville, N.C., or Olympia, Wash. “Whatever made anybody think this would be a better town with a million people,” laments blues singer Ball. “This was a perfect town with 350,000. Now we’ve got Silicon Hills, Barton Springs are cloudy, and drinking water’s going to be scarce. Why is this supposed to be better?”

The drop-off in live music and the belt-tightening by musicians is causing third-party pain for people like veteran Austin journalist and publicist Lynne Margolis, whose national credits include stories for Rolling Stone online, and radio spots for NPR. “The public relations aspect of my work has dropped away because artists can’t afford to pay,” she says, “and music journalism is falling by the wayside. It’s hard not to feel to like a double dinosaur.”

Led by bars, restaurants and music venues, on many days the solemn departure of small establishments has the business news sections of Austin newspapers reading more like the obituary page. One hardy survivor is Giddy Ups – a throwback honky-tonk on the town’s outskirts that advertises itself as “the biggest little stage in Austin” – promising “just about everything,” says owner Nancy Morgan, including “country, blues, rock, bluegrass, and soul.” For the past 20 years Giddy Ups has developed a devoted following of musicians and patrons while fending off hyper modernity.

“It has an untouched, back-to-the-seventies, cosmic cowboy vibe,” says local musician Ethan Ford, a guitarist and bass player whose trio, The Slyfoot Family, has graced its stage. “It’s a time capsule,” Ford adds.

Morgan declined to disclose her annual receipts but in 2019, she reports paying out $188,000 in wages to employees, $72,000 to musicians, and $185,000 in combined sales taxes to the city of Austin and to the state. Despite her status as a taxpayer, employer and entrepreneur, she has received no state aid and is disqualified from receiving city pandemic assistance programs, meager as they may be, because she’s located in an extra-territorial jurisdiction.“

Nancy still bartends most nights and does all of the booking,” says Ford. “Her knowledge of the Austin music scene could fill a couple of books. I know a decent fistful of Austin venue owners and she’s about the only one that hasn’t given up, been forced out, or just retired. She’s a dynamo.”

Unless the cavalry arrives for Morgan and other holdouts, though, their musical days may be numbered.

Editors Note: Threadgill’s didn’t make it. The venue “has closed for good, the property has sold, and the building will eventually be torn down,” according to information disseminated for its Last Call Music Series. Its November 1st grand finale show featured Gary P. Nunn, Dale Watson, Whitney Rose, William Beckman, and Jamie Lin Wilson.

The building will be replaced with apartments.

SBA Simple $50k Forgiveness- Due Next Year

October 15, 2020 On Oct 2nd, the SBA finally released a simple forgiveness process for PPP loans under $50,000. Though many borrowers wanted forgiveness for all loans below $150,000, the under $50k bracket can fill out a one-page, front and back form.

On Oct 2nd, the SBA finally released a simple forgiveness process for PPP loans under $50,000. Though many borrowers wanted forgiveness for all loans below $150,000, the under $50k bracket can fill out a one-page, front and back form.

The SBA recently clarified in a FAQ section that borrowers do not need to submit the forms before the “expiration date” of 10/31/2020 that appears at the upper right corner.

According to the SBA, that expiration date was merely put there to comply with the 1980 Paperwork Reduction Act, which was intended to limit the amount of paperwork that government agencies can send to the public, and that as such it has no actual bearing on anything related to loan forgiveness.

To clarify, the SBA stated that borrowers can submit a forgiveness form at any time before the maturation of the loan, which is anywhere from two to five years from origination. But, loan payments will begin ten months after the borrowers “loan forgiveness covered period.”

Mnuchin and Powell Defend Pandemic Aid Programs, Say Congress Needs to Agree Before They Can Give out More Money

September 23, 2020 Yesterday, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell testified on the COVID response before the House Financial Services Committee.

Yesterday, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell testified on the COVID response before the House Financial Services Committee.

They championed the largest stimulus package in the Nations’s history and said the economy was recovering well.

Mnuchin advocated for bipartisan support of targeted forgivable loans- a second PPP loan for businesses still losing revenue, funded by either a new stimulus, reusing the $130 billion still leftover, or reallocating $200 billion from the Main Street Lending program. Of course, all of that is up to Congress, he said.

“I think there’s broad bipartisan support for extending the PPP in businesses that have had revenue drops for a second check,” Mnuchin said.

Chair of the committee, Maxine Waters D-CA, led the questioning. She asked for removing the loan minimum, and noting the slow economic activity; she said 32% of renters could not pay their bills at the beginning of Sept. Other charges, like the possibility of a second wave, were leveled toward the executives.

In response to questions to the Main Street Lending Program (MSLP,) they argued the program was not designed as a stimulus but as a “backstop” and liquidity to already present loan markets.

This might explain why last month, the Congressional Oversite Committee investigated the MSLP because of its low adoption rate and found many problems.

To date, less than $2 billion of loans are “in the pipeline” out of the $600 billion allocated in April. The program is designed with non-forgivable loans supplied by 509 traditional FDIC insured lenders, at a minimum of $250,000. The majority of these lenders are not accepting new customers, unlike PPP loans facilitated by more than 5,000 lenders to mostly new clients- including fintech firms.

The Fed already lowered the minimum down from $1 million, but after questioning whether it could be lowered to under $100,000, Powell said there was very little demand for loans under $100,000. In response to Representative Andy Barr R-KY, about how the program could be improved to service smaller businesses, Powell responded that the program wasn’t created for that.

“The limit now is $250,000, and we have very little demand below a million, as I told the chair a while back,” Powell said. “We’re not seeing demand for very small loans. And that’s really because the nature of the facility and the things you’ve got to do to qualify, it tends to be larger sized businesses.”

The SBA reported findings from the third round of PPP on Aug 10th. The organization found that loans under $50k were the largest category issued. 68% of the 5,212,128 PPP loans were under $50k, and 87% were under $250k.

GOP Proposes PPP Skinny Bill, Vote Thursday

September 9, 2020 On Tuesday, Senate Republicans introduced a slimmed-down “Skinny Bill” stimulus proposal, offering $500 billion proposed aid that they believe both sides of the aisle can agree on.

On Tuesday, Senate Republicans introduced a slimmed-down “Skinny Bill” stimulus proposal, offering $500 billion proposed aid that they believe both sides of the aisle can agree on.

The Bill will extend PPP loans into the fall with $258 billion and certain small businesses will also be able to receive a second forgivable loan. If passed, the Skinny will also reintroduce weekly unemployment benefits of $300- half the $600 CARES act benefits that ended in July.

The Senate will vote on the proposed bill Thursday afternoon. The vote will test the GOP’s cohesion, which could not garner enough support for the $1 trillion HEALS act introduced in July. To pass, the Bill will need seven Democrat votes and 60 votes overall.

If it passes, it will have to survive the Democrat-controlled house. House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi has already spoken against the Bill, saying it is filled with Republican “poison pills” that cannot pass in the House. House Dems are calling the Bill wholly political. Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell said that if the Bill can not pass, the GOP can demonstrate that Dems are “stonewalling” aid.

Fountainhead CEO Chris Hurn Speaks With deBanked About His Experience With 2020

September 9, 2020Chris Hurn, the CEO of Fountainhead, a national non-bank direct commercial lender based in Lake Mary-FL, recently told deBanked in an interview what his company has experienced in 2020. The company was recently ranked 1,502 on the Inc. 5000 list.

Watch the interview below:

Banks, Non-Banks, Fintech and More Came Through for Lendio on PPP, But it Wasn’t Easy

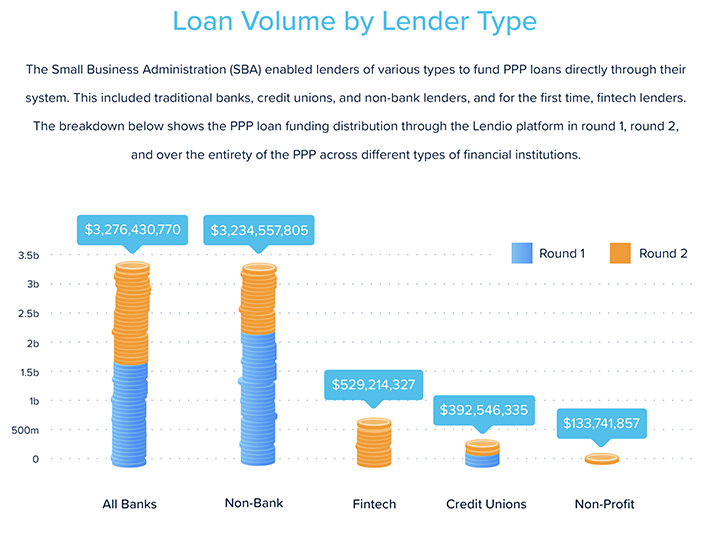

August 27, 2020 Last week, Lendio, a facilitator of small business loans, released a report analyzing the $8 billion of PPP loans that were approved through its lending platform. A coalition of more than 300 lenders was able to give aid, saving an estimated 1.1 million jobs, Lendio indicates.

Last week, Lendio, a facilitator of small business loans, released a report analyzing the $8 billion of PPP loans that were approved through its lending platform. A coalition of more than 300 lenders was able to give aid, saving an estimated 1.1 million jobs, Lendio indicates.

Through Lendio’s service, traditional banks approved the most funding at $3.3 billion- or about 44% of the PPP dollars on the platform. Though non-bank lenders secured the highest number of approvals at 50,264 transactions in lesser dollar amounts.

Fintech lenders funded 6% of the total loan volume through the platform.

Lendio was well situated to facilitate lending from institutions to those that needed help through funds provided by the SBA. Brock Blake, CEO, and co-founder of Lendio, said the company’s success in delivering on PPP was no accident— they had to remove all stops and almost bet on the success of the PPP program.

“Our mission at Lendio is normally ‘Fueling the American Dream’: helping the American business owner accomplish their dream,” Blake said. “We tweaked our mission during this timeframe to ‘Saving the American Dream.'”

Blake said while other companies were closing their doors and sending off employees on furlough, Lendio took on 250 new hires- and buckled down for thousands of hours of engineering work to overhaul their system. Not just loan sales, but legal processes, onboarding, training, and backend tech work had to be updated in just days.

This all came on fast, but so did the quarantine. Beginning in April, more than 100,000 business owners applied for economic relief under the PPP using Lendio’s online marketplace.

The demand for capital was outrageous.

“It was more demand in one weekend than the SBA had seen in the last 14 years combined,” Blake said. “We were helping these business owners that were watching their entire lifes’ work flushed down the drain in a matter of weeks, and they were desperate for capital.”

Lendio was finding that many institutions could simply not handle the volume, Blake said, and he knew if banks were only able to process loan requests for their current customers, there would be an exploding demand for loan processing. The company took on 100 new partners who needed help during this time.

“Our systems were tested to their limits, like 1000 times more pressure than we ever saw before,” Blake said. “Some partners of ours got so much demand they couldn’t handle it and turned off their spigot. So we scrambled to find lenders that would take on new customers.”

Though it was ten times more challenging than anything Blake has done in his career, it was ten times more satisfying. Lendio doubled the number of loans it has issued since 2011, and quintupled the dollar amount the platform facilitated in just four short months. Where are they going to go from here?

For one, Lendio is one company out of many that are hoping for another round of PPP funding. Blake said he is getting customer feedback all the time asking for help, dealing with quarantine regulation that is harming business, like restaurants that have nowhere to seat patrons.

Outside of PPP, Blake said that many of the 110,000 businesses they served are now applying for other loans, or using Lendio’s bookkeeping and loan forgiveness applications. Lendio is happy to help business owners and banks through this tough time by launching digital applications.

“Before, lenders across the country were requiring business owners to come into branches [with] paper applications,” Blake said. “Now, there’s not one business owner in America that wants to walk into a bank branch. The demand for lenders to go digital is as high as it’s ever been.”

CEO Of Online Lender Arrested For PPP Fraud

August 19, 2020 Sheng-wen Cheng, aka Justin Cheng, the CEO of Celeri Network, was arrested on Tuesday by the FBI. Celeri offers business loans, merchant cash advances, SBA loans, and student loans.

Sheng-wen Cheng, aka Justin Cheng, the CEO of Celeri Network, was arrested on Tuesday by the FBI. Celeri offers business loans, merchant cash advances, SBA loans, and student loans.

Cheng applied for over $7 million in PPP funds, federal agents allege, on the basis that Celeri Network and other companies he owns had 200 employees. In reality he only had 14 employees, they say.

Cheng succeeded in obtaining $2.8M in PPP funds but rather than use them for their intended lawful purpose, he bought a $40,000 Rolex watch, paid $80,000 towards a S560X4 Mercedes-Maybach, rented a $17,000/month condo apartment, bought $50,000 worth of furniture, and spent $37,000 while shopping at Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Burberry, Gucci, Christian Louboutin, and Yves Saint Laurent.

He also withdrew $360,000 in cash and/or cashiers checks and transferred $881,000 to accounts in Taiwan, UK, South Korea, and Singapore.

This, of course, is all according to the FBI. Statements made to Law360 indicate that Cheng maintains his innocence.

A press release published by Celeri late last year said that the company had raised $2.5M in seed funding that valued the company at $11M.

IN DEFAULT OR ABOVE WATER: How PPP Saved or Didn’t Save America

July 31, 2020 Kristy Kowal, a silver medalist in the 200-meter breast stroke at the 2000 Olympic games in Australia, had recently relocated to Southern California and embarked on a new career when the pandemic shutdown hit in March.

Kristy Kowal, a silver medalist in the 200-meter breast stroke at the 2000 Olympic games in Australia, had recently relocated to Southern California and embarked on a new career when the pandemic shutdown hit in March.

After nearly two decades as a third-grade teacher in Pennsylvania, Kowal was able to take early retirement in 2019 and pursue her dream job. At last, she was self-employed and living in Long Beach where she could now devote herself to putting on swim clinics, training top athletes, and accepting speaking engagements. “I’ve been building up to this for twenty years,” she says.

But fate had a different idea. The coronavirus not only grounded her from travel but closed down most swimming pools. At first, she tried to collect unemployment compensation. But after two months of calling the unemployment office every day, her claim was denied. “‘Have a great day,’ the lady said, and then she hung up,” Kowal reports. “She wasn’t rude; she just hung up.”

Then, in June, the former Olympian heard from friends about Kabbage and the Paycheck Protection Program. Using an app on her smart phone, Kowal says, she was able to upload documents and complete the initial application in fewer than 20 minutes. A subsequent application with a bank followed and within a week she had her money.

“I was down to ten cents in my checking account,” says Kowal, who declined to disclose the amount of PPP money for which she qualified, “and I’d begun dipping into my savings. This gives me the confidence that I need to go back to my fulltime work.”

Kowal is one of 4.9 million small business owners and sole proprietors who, according to the U.S. Small Business Administration, has received potentially forgivable loans under the Paycheck Protection Program. The PPP, a safety-net program designed to pay the wages of employees for small businesses affected by the coronavirus pandemic, is a key component of the $1.76 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act). Since the U.S. Congress enacted the law on March 27, the PPP has been renewed and amended twice. It’s now in its third round of funding and Congress is weighing what to do next.

Kowal is one of 4.9 million small business owners and sole proprietors who, according to the U.S. Small Business Administration, has received potentially forgivable loans under the Paycheck Protection Program. The PPP, a safety-net program designed to pay the wages of employees for small businesses affected by the coronavirus pandemic, is a key component of the $1.76 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act). Since the U.S. Congress enacted the law on March 27, the PPP has been renewed and amended twice. It’s now in its third round of funding and Congress is weighing what to do next.

Kowal’s experience, meanwhile, is also a wake-up call for the country on the prominent role that both fintechs like Kabbage as well as community and independent banks, credit unions, non-banks and other alternatives to the country’s biggest banks play in supporting small business. Before many in this cohort were deputized by the SBA as full-fledged PPA lenders, a significant chunk of U.S. microbusinesses – especially sole proprietorships — were largely disdained by the brand-name banks.

“After the first round,” notes Karen Mills, former administrator of the U.S. Small Business Administration and a senior fellow at the Harvard Business School, “more institutions were approved that focused on smaller borrowers. These included fintechs and I have to say I’ve been very impressed.”

Among the cadre of fintechs making PPP loans – including Funding Circle, Intuit Quickbooks, OnDeck, PayPal, and Sabre — Kabbage stands out. The Atlanta-based fintech ranked third among all U.S. financial institutions in the number of PPP credits issued, its 209,000 loans trailing only Bank of America’s 335,000 credits and J.P. Morgan Chase’s 260,000, according to the SBA and company data. Kabbage also reports processing more than $5.8 billion in PPP loans to small businesses ranging from restaurants, gyms, and retail stores to zoos, shrimp boats, beekeepers, and toy factories.

To reach businesses in rural communities and small towns, Kabbage collaborated with MountainSeed, an Atlanta-based data-services provider, to process claims for 135 independent banks and credit unions around the U.S. The proof of the pudding: Eighty-nine percent of Kabbage’s PPP loans, says Paul Bernardini, director of communications at Atlanta-based Kabbage, were under $50,000, and half were for less than $13,500.

The figures illustrate not only that Kabbage’s PPP customers were mainly composed of the country’s smaller, “most vulnerable” businesses, Bernardini asserts, but the numbers serve as a reminder that “fintechs play a very important, vital role in small business lending,” he says.

The helpfulness of such financial institutions contrasts sharply with what many small businesses have reported as imperious indifference by the megabanks. Gerri Detweiler, education director at Nav, Inc., a Utah-based online company that aggregates data and acts as a financial matchmaker for small businesses, steered deBanked toward critical comments about the big banks made on Nav’s Facebook page. Bank of America, especially, comes in for withering criticism.

“Bank of America wouldn’t even take my application,” one man wrote in a comment edited for brevity. “I have three accounts there. They are always sending me stuff about what an important client I am. But when the going got tough, they wouldn’t even take my application. I’m moving all my business from Bank of America.”

Lamented another Bank of America customer: “I was denied (PPP funding) from Bank of America (where) I have an individual retirement account, personal checking and savings account, two credit cards, a line of credit for $20.000, and a home mortgage. Add in business checking and a business credit card. Yesterday I pulled out my IRA. In the next few days I’m going to change to a credit union.”

Many PPP borrowers who initially got the cold shoulder from multi-billion-dollar conglomerate banks have found refuge with local — often small-town — bankers and financial institutions. Natasha Crosby, a realtor in Richmond, Va., reports that her bank, Capital One, “didn’t have the applications available when the Paycheck Protection Program started” on April 6. And when she finally was able to apply, she notes, “the money ran out.”

Crosby, who is president of Richmond’s LGBTQ Chamber of Commerce, is media savvy and was able to publicize her predicament through television appearances on CNN and CBS, as well as in interviews with such publications as Mother Jones and Huffington Post. A “friendly acquaintance,” she says, referred her to Atlantic Union Bank, a Richmond-based regional bank, where she eventually received a PPP loan “in the high five figures” for her sole proprietorship.

“It took almost two months,” Crosby says. “I was totally frozen out of the program at first.”

Talibah Bayles heads her own firm, TMB Tax and Financial Services, in Birmingham, Ala. where she serves on that city’s Small Business Council and the state’s Black Chamber of Commerce. She told deBanked that she’s seen clients who have similarly been decamping to smaller, less impersonal financial institutions. “I have one client who just left Bank of America and another who’s absolutely done with Wells Fargo,” she says. “They’re going to places like America First Credit Union (based in Ogden, Utah) and Hope Credit Union (headquartered in Jackson, Miss.). I myself,” she adds, “shifted my business from Iberia Bank.”

Main Street bankers acknowledge that they are benefiting from the phenomenon. “In speaking to our industry colleagues,” says Tony DiVita, chief operating officer at Bank of Southern California, an $830 million-asset community bank based in San Diego, “we’ve seen that many of the big banks have slowed down or stopped lending small-dollar amounts that were too low for them to expend resources to process.”

Main Street bankers acknowledge that they are benefiting from the phenomenon. “In speaking to our industry colleagues,” says Tony DiVita, chief operating officer at Bank of Southern California, an $830 million-asset community bank based in San Diego, “we’ve seen that many of the big banks have slowed down or stopped lending small-dollar amounts that were too low for them to expend resources to process.”

At the same time, DiVita says, his bank had made 2,634 PPP loans through July 17, roughly 80% of which went to non-clients. Of that number, some 30% have either switched accounts or are in the process of doing so. And, he notes, the bank will get a second crack at conversion when the PPP loan-forgiveness process commences in earnest. “Our guiding spirit is to help these businesses for the continuation of their livelihoods,” he says.

Noah Wilcox, chief executive and chairman of two Minnesota banks, reports that both of his financial institutions have been working with non-customers neglected by bigger banks where many had been longtime customers. At Grand Rapids State Bank, he says, 26% of the 198 PPP applicants who were successfully funded were non-customers. Minnesota Lakes Bank in Delano, handled PPP credits for 274 applicants, of whom 66% were non-customers.

“People who had been customers forever at big banks told us that they had been applying for weeks and were flabbergasted that we were turning those applications around in an hour,” says Wilcox, who is also the current chairman of the Independent Community Bankers of America, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing community banks.

Noting that one of his Gopher State banks had successfully secured funding for an elderly PPP borrower “who said he had been at another bank for 69 years and could not get a telephone call returned,” Wilcox added: “We’ve had quite a number of those individuals moving their relationships to us.”

For Chris Hurn, executive director at Fountainhead Commercial Capital, a non-bank SBA lender in Lake Mary, Fla., the psychic rewards have helped compensate for the sometimes 16-hour days he and his staff endured processing and funding PPP applications. “It’s been relentless,” he says of the regimen required to funnel loans to more than 1,300 PPP applicants, “but we’ve gotten glowing e-mails and cards telling us that we’ve saved people’s livelihoods.”

Yet even as the Paycheck Protection Program – which only provides funding for two-and-a-half months – is proving to be immensely helpful, albeit temporarily, there is much trepidation among small businesses over what happens when the government’s spigots run dry. The hastily contrived design of the program, which has relied heavily on the country’s largest financial institutions, has contributed mightily to the program’s flaws.

“The underbanked and those who don’t have banking relationships were frozen out in the first round,” says Sarah Crozier, director of communications at Main Street Alliance, a Washington D.C.-based advocacy organization comprising some 100,000 small businesses. “The new updates were incredibly necessary and long overdue,” she adds, “but the changes didn’t solve the problem of equity in access to the program and whom money is flowing to in the community.”

Professor David Audretsch, an economist at Indiana University’s O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs and an expert on small business, says of PPP: “It’s a short-term fix to keep businesses afloat, but it missed in a lot of ways. It was not well-thought-out and a lot of money went to the wrong people.”

The U.S. unemployment rate stood at 11.1% in June, according to the most recent figures released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, about three times the rate of February, just before the pandemic hit. The BLS also reported that 47.2% of the U.S. population – nearly half –was jobless in June. Against this backdrop, SBA data on PPP lending released in early July showed that a stunning array of cosseted elite enterprises and organizations, many with close connections to rich and powerful Washington power brokers, have been feasting on the PPP program.

In a stunning number of cases, the program’s recipients have been tony Washington, D.C. law firms, influential lobbyists and think tanks, and even members of Congress. Many businesses with ties to President Trump and Trump donors have also figured prominently on the SBA list of those receiving largesse from the SBA.

Businesses owned by private equity firms, for which the definition of “small business” strains credulity, were also showered with PPP dollars. Bloomberg News reported that upscale health-care businesses in which leveraged-buyout firms held a controlling interest, were impressively adept at accessing PPP money. Among this group were Abry Partners, Silver Oak Service Partners, Gauge Capital, and Heron Capital. (Small businesses are generally defined as enterprises with fewer than 500 employees. The SBA reports that there are 30.7 million small businesses in the U.S. and that they account for roughly 47% of U.S. employment.)

Businesses owned by private equity firms, for which the definition of “small business” strains credulity, were also showered with PPP dollars. Bloomberg News reported that upscale health-care businesses in which leveraged-buyout firms held a controlling interest, were impressively adept at accessing PPP money. Among this group were Abry Partners, Silver Oak Service Partners, Gauge Capital, and Heron Capital. (Small businesses are generally defined as enterprises with fewer than 500 employees. The SBA reports that there are 30.7 million small businesses in the U.S. and that they account for roughly 47% of U.S. employment.)

Boston-based Abry Partners, which currently manages more than $5 billion in capital across its active funds, merits special mention. Among other properties, Abry holds the largest stake in Oliver Street Dermatology Management, recipient of between $5 million and $10 million in potentially forgivable PPP loans. Based in Dallas, Oliver Street ranks among the largest dermatology management practices in the U.S. and, according to a company statement, boasts the most extensive such network in Texas, Kansas and Missouri.

Meanwhile, the design of the program and the formula for the looming forgiveness process is proving impractical. As it currently stands, loan forgiveness depends on businesses spending 60% of PPP money on employees’ wages and health insurance with the remaining 40% earmarked for rent, mortgage or utilities.

Many businesses such as restaurants and bars, storefront retailers and boutiques – particularly those that have shut down — are preferring to let their employees collect unemployment compensation. “Business owners had a hard time wrapping their heads around the requirement of keeping employees on the payroll while they’re closed,” notes Detweiler, the education director at Nav. “They have other bills that have to be paid.”

Many businesses such as restaurants and bars, storefront retailers and boutiques – particularly those that have shut down — are preferring to let their employees collect unemployment compensation. “Business owners had a hard time wrapping their heads around the requirement of keeping employees on the payroll while they’re closed,” notes Detweiler, the education director at Nav. “They have other bills that have to be paid.”

The forgiveness formula remains vexing for businesses where real estate costs are exorbitant, particularly in high-rent cities such as New York, Boston, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Chicago. Tyler Balliet, the founder and owner of Rose Mansion, a midtown Manhattan wine-bar promising an extravagant, theme-park experience for wine enthusiasts, says that it took him a month and a half to receive almost $500,000 from Chase Bank. Unfortunately, though, the money isn’t doing him much good.

“I have 100 employees on staff, most of whom are actors,” he says. “We shut down on March 13. I laid off 95 employees and kept just a few people to keep the lights on.”

At the same time, his annual rent tops $1 million and the forgivable amount in the PPP loans won’t even cover a month’s rent. “I haven’t paid rent since March and I’m in default,” Balliet says. “Now I’m just waiting to see what the landlord wants to do.”

Like many business owners, Balliet financed much of his venture with credit card debt, which creates an additional liability concern, notes Crozier of the Main Street Alliance. “It’s very common for borrowers to have signed personal guarantees in their loans using their credit cards,” she says. “As we get closer to the funding cliff and as rent moratoriums end,” she adds, “creditors are coming after borrowers and putting their personal homes at risk.”

Mark Frier is the owner of three restaurants in Vermont ski towns, including The Reservoir — his flagship — in Waterbury. In toto, his eateries chalked up $6.5 million in combined sales in 2019. But 2020 is far different: the restaurants have not been open since mid-March and he’s missed out on the lucrative, end-of-season ski rush.

Consequently, Frier has been reluctant to draw down much of the $750,000 in PPP money he’d secured through local financial institutions. “We could end up with $600,000 in debt even with the new rules,” Frier says, adding: “We live off very thin margins. We need grants not loans.”

As the country recorded 3.7 million confirmed cases of coronavirus and more than 141,000 deaths as of mid-July, PPP money earmarked by businesses for health-related spending was not deemed forgivable. Yet in order to comply with regulations promulgated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and mandates and ordinances imposed by state and local governments, many establishments will be unable to avoid such expenditures.

“What we really needed was a grant program for companies to pivot to a business environment in a pandemic,” says Crozier. She cites the necessity businesspeople face of “retrofitting their businesses, buying masks, gloves and sanitizers and cleaning supplies, restaurants’ taking out tables and knocking down walls, installing Plexiglass shields, and improving air filtration systems.”

Meanwhile, as Covid-19 was taking its toll in sickness and death, the economic outlook for small business has been looking dire as well. The recent U.S. Census’s “Pulse Survey” of some 885,000 businesses updated on July 2 found that roughly 83% reported that Covid-19 pandemic had a “negative effect on their business. Fully 38% of all small business respondents, moreover, reported a “large negative effect.”

Meanwhile, as Covid-19 was taking its toll in sickness and death, the economic outlook for small business has been looking dire as well. The recent U.S. Census’s “Pulse Survey” of some 885,000 businesses updated on July 2 found that roughly 83% reported that Covid-19 pandemic had a “negative effect on their business. Fully 38% of all small business respondents, moreover, reported a “large negative effect.”

Amid the unabated spikes in the number of coronavirus cases and the country’s grave economic distress, PPP recipients are faced with the unsettling approach of the PPP forgiveness process. As Congress, the SBA, and the U.S. Treasury Department continue to remake and revise the rules and regulations governing the program, businesses are operating in a climate of uncertainty as well. Currently, the law states that the amount of the PPP loan that fails to be forgiven will convert to a five-year, one-percent loan — a relaxation in terms from the original two-year loan which is not necessarily cheering recipients.

“One of the biggest problems with PPP is that the rule book has been unclear,” frets Vermont restaurateur Frier, glumly adding: “This is not even a good loan program.”

Ashley Harrington, senior counsel at the Center for Responsible Lending, a research and policy group based in Durham, N.C., argued in House committee testimony on June 17, that there ought to be automatic forgiveness for PPP loans under $100,000. Such a policy, she declared, “would likely exempt firms with, on average, 13 or fewer employees and save 71 million hours of small business staff time.”

She also said, “The smallest PPP loans are being provided to microbusinesses and sole proprietors that have the least capacity and resources to engage in a complex (forgiveness) process with their financial institution and the SBA.”

William Phelan, president of Skokie (Ill.)-based PayNet, a credit-data services company for small businesses which recently merged with Equifax, sounded a similar note. Observing that there are some 23 million “non-employer” small businesses in the U.S. with fewer than three employees for whom the forgiveness process will likely be burdensome, he says: “Estimates are that it will cost businesses a few thousand dollars just to get a $100,000 loan forgiven. It’s going to involve mounds of paper work.”

The country’s major challenge now will be to re-boot the economy, Phelan adds, which will require massive financing for small businesses. “The fact is that access to capital for small businesses is still behind the times,” Phelan says. “At the end of the day, it took a massive government program to insure that there’s enough capital available for half of the U.S. economy” during the pandemic.

For his part, Professor Audretsch fervently hopes that the country has learned some profound lessons about the need to prepare for not just a rainy day, but a rainy season. The pandemic, he says, has exposed how decades of political attacks on government spending for disaster-preparedness and safety-net programs have left the U.S. exposed to unforeseen emergencies.

“We’re seeing the consequence of not investing in our infrastructure,” he says. “That’s a vague word but we need a policy apparatus in place so that the calvary can come riding in. This pandemic reminds me a lot of when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans,’ he adds. “The city paid a heavy price because we didn’t have the infrastructure to deal with it.”