Should I Start an ISO With Only $2,000?

January 12, 2015A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…

It is a period of civil war. Rebel sales reps, striking from a hidden ISO, have won their first victory against the evil Galactic Funder.

During the battle, Rebel spies managed to steal secret formulas to the Funder’s ultimate weapon, the UNDERWRITING ALGORITHM, an advanced code with enough power to destroy an entire industry.

Pursued by the Funder’s sinister sales agents, our hero races home with her flash drive, custodian of the stolen formulas that can save her merchants and restore freedom to the industry…

Breaking away to start your own ISO or brokerage in this industry used to be a rite of passage. You started somewhere, learned the ropes, then went off on your own like a Jedi Master.

The stories of reps and underwriters of years past who left their jobs to start their own ISOs are a bit nostalgic. Young twenty-somethings defying authority to plant their own flags in an industry they felt offered unlimited potential. For some, going solo was a rude awakening, a healthy taste of the real world, where you needed to be able to do more than just close the leads you’re given. But for others? Well, today they are the owners or managers of companies worth millions, tens of millions, or hundreds of millions of dollars.

Empires were built not that long ago and they certainly were not in a galaxy far, far away. But today the prospects are much bleaker. The industry has matured and certain channels are saturated. Merchant cash advance and non-bank business lending are no longer part of a young unexplored universe.

So to those that have asked me whether or not it makes sense to start an ISO in 2015, I’d have to say in many cases it does not. It’s a little late in the game. Below is one of the most popular questions posed to me over the last six months:

Q: I’m thinking about starting my own ISO. I have about $2,000 to $5,000 to spend on leads. Do you think I can do it and where should I buy the best leads from?

Q: I’m thinking about starting my own ISO. I have about $2,000 to $5,000 to spend on leads. Do you think I can do it and where should I buy the best leads from?

A: There’s a few things to address here. If you are working out of your house and your rent/mortgage is already taken care of without you having to pay yourself from your new ISO, you may be able to turn a profit starting with something this small. The first problem though is that if you’re not absolutely positive where to get excellent leads, you’re going to spend a lot of money on experimenting with multiple sources. $2,000 might be the cost of an experiment with one lead provider. In other cases, it might be $5,000. Your entire budget could get wiped out in an experiment with just one source.

There may be no barriers to entry in this business, but $2,000 to $5,000 is entirely too little to give yourself a real chance to get off the ground. Direct mail takes a lot of trial and error and thousands of dollars. Google/Bing advertising takes even more trial and error and tens of thousands of dollars before you can get really meaningful results.

And if you’re going to put all your eggs in the UCC marketing basket because of budget, it’s going to be a tough climb uphill.

The companies that do actually have the best leads don’t need a $2,000 startup ISO to sell them to. A big ISO or funder is probably already paying double the price they’re worth.

So how do you stand a chance? You should realize that the odds are you won’t.

And if you need to allocate part of that 2-5k to pay for an office and get set up like a business, you might not have anything left for marketing at all. That’s a horrible place to be!

Lastly, I have seen many ISOs try to become a broker’s broker in order to acquire deals. That means trying to close ISOs to send you deals for you to forward on to a funder as a middleman where you will get a cut if the deal closes. It’s a hustle, and if you can swing this, great, but it’s not exactly a sustainable model especially if the ISO realizes they can go direct to the funder themselves. If you can’t acquire merchants on your own (and deals you stole from the last place you worked at don’t count as acquiring on your own), then you probably shouldn’t be in the ISO business at all.

If you’re going to start an ISO in 2015, I suggest having a minimum $25,000 (50k to be safe) in marketing to start off. And if you don’t know what you’re doing, well then may the force be with you.

Heather Francis Launching New Funding Company

January 5, 2015 One of the Six Women of Alternative Finance is leaving their current position to launch their own funding company. Heather Francis, EVP of Merchant Cash Group appeared in the September/October issue of DailyFunder. A regular at the industry’s conferences and who was in many ways the face of Merchant Cash Group, Francis is moving on to start Elevate Funding.

One of the Six Women of Alternative Finance is leaving their current position to launch their own funding company. Heather Francis, EVP of Merchant Cash Group appeared in the September/October issue of DailyFunder. A regular at the industry’s conferences and who was in many ways the face of Merchant Cash Group, Francis is moving on to start Elevate Funding.

When the news broke, deBanked asked Francis about the change. This was her response:

“So the start of the new year begins with something exciting for me as I will be leaving Merchant Cash Group to pursue heading up my own funding company. Elevate funding is still in the set up stages and will not be operational and funding until Mid February but I can assure you that with each unveiling of what we will be funding and what we will offer to the Alternative Industry as well as the business owners will help shape a new future. I enjoyed my time at Merchant Cash Group and I wish them all the best but I am excited for this new adventure and to take a lot of the ideas that have been kicking in my head for a while and see them come to fruition. I know it will be difficult and I am greatly looking forward to the challenge. In the words of a Fort Minor song : This is 10% luck, 20% skill, 15% concentrated power of will, 5% pleasure , 50% pain, and a 100% reason to remember the name… Best of luck to all in 2015!”

Elevate will be based in Gainesville, FL.

Through OnDeck Capital, An Industry Wins

December 16, 2014 Call it merchant cash advance, non-bank business lending, or financial disintermediation. Whatever floats your boat. On December 17th an entire financial methodology will be validated, the daily repayment method. Daily payments don’t exist anywhere else in lending but ’round these parts it’s the standard. It’s what makes unbankable businesses bankable.

Call it merchant cash advance, non-bank business lending, or financial disintermediation. Whatever floats your boat. On December 17th an entire financial methodology will be validated, the daily repayment method. Daily payments don’t exist anywhere else in lending but ’round these parts it’s the standard. It’s what makes unbankable businesses bankable.

OnDeck is a lender. They target small businesses. The costs are high. Anyone could feasibly do those things and plenty are doing them, but only a certain segment of fintech companies utilize daily payments and most of those are merchant cash advance companies. OnDeck is a lender but like it or not their core repayment mechanism overlaps with an industry well known for being even more expensive.

Daily payments are so unique and so revolutionary that it hasn’t sunk in to the masses yet. Even the press glosses over this fine detail to instead dwell on things like APRs and social media’s role in approvals. Daily payment and daily repayment look like tech jargon, some kind of code for a backend computer process to hotwire an anomalous rate algorithm.

Daily payments mean borrowers have to make payments every single business day. It’s daily, get it? If the sun rises and it’s not Saturday or Sunday, it’s time to make a payment. I’m not saying there’s something wrong with this. I’m a proponent of this mechanism. It works for business owners that struggle to make a single lump sum payment each month and it works for lenders who need to mitigate and monitor their risk as much as possible.

I feel it’s better to know there was a problem that started yesterday than to learn there was a problem that started 29 days ago. That’s how OnDeck thinks too. And business owners can incorporate the daily deduction into their normal business operations instead of fretting to cover the balance for a big debit the day before a monthly payment is due.

I feel it’s better to know there was a problem that started yesterday than to learn there was a problem that started 29 days ago. That’s how OnDeck thinks too. And business owners can incorporate the daily deduction into their normal business operations instead of fretting to cover the balance for a big debit the day before a monthly payment is due.

This isn’t just a theoretical design that can’t function in practice. It’s been working for lenders and factors since AdvanceMe (Now CAN Capital) started doing it in 1998. The daily payment methodology has survived the Dot Com Bust and the Great Recession. It’s grown to a $3 – $5 billion a year industry. By some measures, it’s taken a hell of a long time to go this mainstream.

But it’s here. The press will call OnDeck a lender, a tech company, or a combination of both. They’re a sign of the times but they are unique in that they will show the world that daily payments have a place in the modern economy. With OnDeck leading the way, traditional lenders may consider leveraging their methodology to serve categories of risk they usually shy away from.

I’ve never heard of a business credit card that required payments to be made every day. Some might think that defeats the purpose of credit. OnDeck proves it doesn’t. And 100+ merchant cash advance companies serve as a secondary validation. Perhaps there are lenders that have considered a daily payment system previously and feared the political or legal environment was too risky. But OnDeck is making no apology about what they’re doing or how they’re doing it. They’re putting themselves on the open market, surrendering themselves to total scrutiny.

CAN Capital is gearing up to follow them, the pioneers who first experimented with daily payments 16 years ago. And while OnDeck bemoans their loan program being compared to merchant cash advance, CAN is made up of two departments, one of which is undoubtedly a merchant cash advance service provider.

CAN Capital is gearing up to follow them, the pioneers who first experimented with daily payments 16 years ago. And while OnDeck bemoans their loan program being compared to merchant cash advance, CAN is made up of two departments, one of which is undoubtedly a merchant cash advance service provider.

And there you have it. It’s not all about algorithms or tech or using facebook activity to judge a borrower. Those are old ideas now. OnDeck smashes down the door with something completely different, something that nobody is even talking about, daily payments.

December 17th is Wednesday and just about all of OnDeck’s borrowers will be making a payment. A good many of them won’t even notice. That’s the great part about layering it in as a daily cash flow expense. There’s no worrying about it at the end of the month. If they underwrite the borrower financials well enough, it should be completely painless. That’s not always the case, but it’s the goal.

You can’t possibly understand OnDeck until you understand daily payments. With this IPO, an entire industry wins.

Merchant Cash Advance Underwriting For Humans

December 11, 2014 There is no doubt that the merchant cash advance industry has undergone significant expansionary changes within the past decade. The first-mover advantage is past its prime in this industry and no longer proves to be as profitable as it once was for some of the earlier entrants to the market.

There is no doubt that the merchant cash advance industry has undergone significant expansionary changes within the past decade. The first-mover advantage is past its prime in this industry and no longer proves to be as profitable as it once was for some of the earlier entrants to the market.

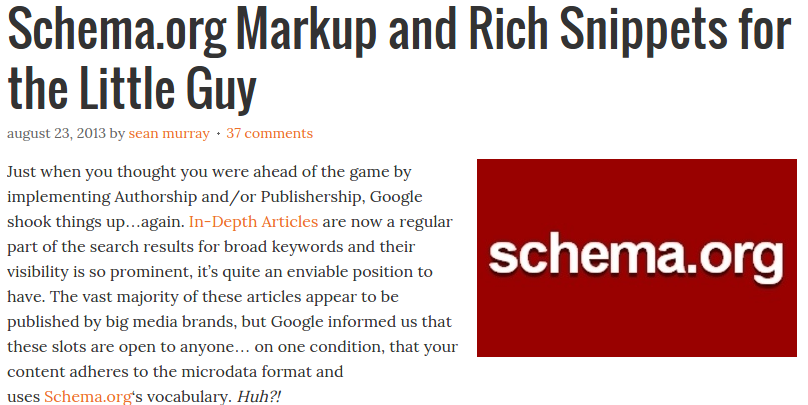

Although the alternative lending industry still has not garnered enough attention for change and reform from policymakers, it has attracted attention from Wall Street and wealthy Main Street investors alike. As today’s merchant cash advance providers continue to grow their capital bases, these larger players have the option and arguably an incentive to explore new products that will help them capture a larger market share of small businesses financing needs and ultimately will help them improve their bottom line.

Several of the more established companies have continued to grow either organically through strategic leadership and good timing, while others have been able to grow and cover new markets through mergers and acquisitions. Of all changes that have been affecting this space, one of the more interesting ones is the introduction of proprietary software used by some of these companies that will allow them to pre-qualify a merchant based on an online application, rate their credit risk, briefly scan submitted bank statements, merchant account statements and financial statements.

Several companies in this industry have invested extensively into making this process a reality, believing it will help them excel against their competitors by creating an economies of scope situation.

Not so fast though…

While automation can help make a company more efficient by converting applications into funded accounts, it can also create a gap in a company’s risk management policies if the company does not have steps in the process to reduce two important risks in any financial services business:

a) Information Asymmetry

b) fraud detection.

For those companies that still use human underwriters, I have compiled some pointers on my experiences relating to things I pay tremendous attention to when underwriting new accounts that help me spot fraudulent documents.

The starting point in the fraud detection process begins with the application and a thorough review of the information provided. Google everything. Make sure the business is not reported as being closed, that the merchant is not going through extensive litigation that could result in jail time or in the business being sold off to another individual. Information on the internet is bountiful, and most of it is completely free. Unlike traditional financial services companies, he who pays the piper calls the tune does not apply in the alternative finance industry. Merchants are almost completely unbound with how to spend their advance, and sometimes engage in reckless borrowing to achieve their means, oftentimes altering documents in the process.

The starting point in the fraud detection process begins with the application and a thorough review of the information provided. Google everything. Make sure the business is not reported as being closed, that the merchant is not going through extensive litigation that could result in jail time or in the business being sold off to another individual. Information on the internet is bountiful, and most of it is completely free. Unlike traditional financial services companies, he who pays the piper calls the tune does not apply in the alternative finance industry. Merchants are almost completely unbound with how to spend their advance, and sometimes engage in reckless borrowing to achieve their means, oftentimes altering documents in the process.

Credit Reports

In my experience with underwriting, many of the fraudulent accounts that I view have owners with either bad credit, limited credit history or no credit history. Furthermore, pay close attention to any fraud alerts on the 1st page of the report, and especially the date of the alert if it is fairly recent. Lastly, pay close attention to the number of recent inquiries on the credit inquiries. Today’s small businesses receive dozens of inquiries from cash advance companies and ISOs. While the inquiries themselves do not outright indicate any fraud and may even be encouraged by ISOs looking to get their merchant the best deal, the combination of a fraud alert and say 20 inquiries from competitive cash advance companies could signify that the other competitors found something that may not add up on the file and will warrant a close eye on the other submitted documents.

Bank Statements

Through community websites, fraudulent bank statements, merchant account statements, or any other type of statement are made easily accessible to purchase. The number of submitted fraudulent bank statements that I have seen within the past year has dramatically increased. Some statements can take as little as 5 seconds to determine if they are fraudulent and there are others that are so clever that they can take close to an hour of close scrutiny to find.

I personally use Adobe Acrobat to read and navigate through bank statements. Some of these statements are doctored so well that you may have to zoom in upwards of 300% to find a comma that should actually be a period to separate dollars from cents to put as a simple example. Be sure to quickly glance over all the statements, checking to see that you have a complete page sequence and the page count is correct.

One of the more common amateur mistakes is to use a prior year’s bank statement and simply change the year to read current year. Fortunately for underwriters, that process is not as simple as it seems on the surface. Not only do they have to make changes on the header of every page, but many times banks and credit unions make announcements throughout the statement for the current year. Other statements include full dates (month, day, year) on some line items usually in the withdrawals section but sometimes in deposits, subtotals and totals. This is more work for merchants to alter, and leaves them more prone to forgetting to change one of the dates.

Just one inconsistency that happens to somehow conveniently flow with the rest of the statement can be the only evidence that you need. Some of the other common amateur mistakes include poor spelling throughout the statement, whiting out of numerical figures, inconsistent margin changes, font changes, and repetitive use of the same check numbers paid month after month (excluding those with default 0’s or 1’s issued by bank tellers directly).

Just one inconsistency that happens to somehow conveniently flow with the rest of the statement can be the only evidence that you need. Some of the other common amateur mistakes include poor spelling throughout the statement, whiting out of numerical figures, inconsistent margin changes, font changes, and repetitive use of the same check numbers paid month after month (excluding those with default 0’s or 1’s issued by bank tellers directly).

Some of the more well hidden fraud can usually be found by comparing the summary page and last page of the bank statement to other statements. Typically, most banks and some credit unions offer you a snapshot of the starting balance, which should generally match up with the ending balance of the previous month. If it doesn’t, you should look for any transactions from the previous month that did not settle until the current month. If there is none, this is usually a red flag indicating that the merchant forgot that statements are continual time series financial data whose totals carry on to the following month.

Also, be sure to check that the summary data at the beginning of each statement matches the counts for deposits, withdrawals, and checks written each month. I’m also particularly skeptical when I see unusual consistency in the number and value of summary data with very little bank activity. Such an example would be a bank statement that consistently shows only 3-4 deposits each for over $100,000 and miniscule withdrawals such as a few small checks or a handful of fast food POS debits comprising all withdrawals for example. The business could be legitimate and the merchant simply submitted the wrong bank statement, which does not allow you to see the better cash flow picture from first glance, or the merchant could have simply taken the easy way out in creating a basic bank statement. Again, it is helpful to reference the type of business that you are underwriting in order to see if these transactions make sense. I am much more willing to acknowledge and accept this type of statement from a construction company per se than a brick-and-mortar retail shop.

Final Tips

Final Tips

Don’t let analysis paralysis stop you from sticking to your conviction on an account. Underwriting is not directly focused on generating revenue for a firm, but rather minimizing bad debt expenses at the end of the day. If you feel like something is off on the statements that you are looking at but you just cannot find what is wrong, step away from your computer for a few minutes and focus on something else. When you return to your computer, you’ll better be able to scrutinize the statements and more likely to catch something miniscule that you may have missed from closely going over the statements again and again.

You can also ask fellow colleagues to look at the statements. Try experimenting and let at least one know that you have suspicions on a particular account and if they could take a close look at the statements; it also helps if you have someone else simultaneously looking at the same account but do not tell them about your suspicions on the account. If they also have a strange feeling about the statements, chances are that there is something off that warrants even closer examination. Lastly, when in doubt try to confirm the statements with the source of the statement. It may be beneficial to request that your merchants provide you with a bank representative’s contact information so that you can verify the legitimacy with the bank yourself.

Another source of action would be to have a merchant provide your company with a view only access of the account. This would also allow you to directly confirm the legitimacy of the statements eliminating any left over suspicions. The only downsides to these last two approaches is that they make take some time to complete, oftentimes a merchant is not willing to wait a few more days and will willingly go to a competitor who can promise to have them funded within 24 hours. In these cases, your last line of defense comes down to the merchant interview part of the process.

2014 was an unbelievable year!

2014 was an unbelievable year!

Back in July 2010, I launched www.merchantprocessingresource.com as an independent resource for merchant processing and merchant cash advance. At that time I was celebrating my 4th anniversary of working in the merchant cash advance business and realized there was little to no information about the industry online.

Back in July 2010, I launched www.merchantprocessingresource.com as an independent resource for merchant processing and merchant cash advance. At that time I was celebrating my 4th anniversary of working in the merchant cash advance business and realized there was little to no information about the industry online.  The volume of emails have slowed but I’ve somehow ended up on robo calling lists. “Press 1 to talk to a funding specialist or press 9 to be added to the Do Not Call list”

The volume of emails have slowed but I’ve somehow ended up on robo calling lists. “Press 1 to talk to a funding specialist or press 9 to be added to the Do Not Call list”