Legal Briefs

Plot Twist: Obama Administration to Comment on Madden v Midland

March 22, 2016

The U.S. Supreme Court wants to know what the Obama administration thinks of the Madden v Midland case.

The potential impact of Madden v Midland on marketplace lending was finally starting to fade away until the U.S. Supreme Court made an unexpected move yesterday. “The Solicitor General is invited to file a brief in this case expressing the views of the United States,” the docket states. At issue is the scope of preemption under the National Bank Act (i.e. can you buy a loan issued by a nationally chartered bank that legally circumvented state usury laws at the time it was originated and still enforce the interest rate?)

The Solicitor General is responsible for arguing cases on behalf of the U.S. government in the U.S. Supreme Court. The position is appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. That seat is currently filled by Donald B. Verrilli, Jr., an Obama appointee and the man credited with saving Obamacare. He was the attorney that helped persuade the Supreme Court to treat the individual mandate of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act as a tax and not as an exercise of Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause.

Any brief filed is bound to become politically significant since the Obama Administration is on its way out. Therefore any views it expresses in the next few months may not be the same views of the next administration scheduled to be sworn in ten months from now.

Madden v Midland will have no bearing on merchant cash advances and little if any bearing on commercial marketplace lenders. That’s because most not only work with state chartered banks instead of nationally chartered banks, but also face more favorable state usury laws since they do not lend to consumers.

Ohio Considers Regulation of Confessions of Judgment

March 20, 2016 In a commercial lending context, courts and legislatures have generally assumed that the parties to the agreement have relatively equal bargaining power. Because of this understanding – that a business borrower is more sophisticated than a consumer borrower – regulation has been more “hands off” with regard to the terms commercial loans may contain. One such clause frequently found in commercial loan agreements is a confession of judgment clause, also called a cognovit judgment. A confession of judgment is written authorization by the borrower directing the entry of a judgment against him in the event he defaults on payment. A confession of judgment clause in a loan agreement permits the creditor on default to appear in court and confer judgment against the borrower.

In a commercial lending context, courts and legislatures have generally assumed that the parties to the agreement have relatively equal bargaining power. Because of this understanding – that a business borrower is more sophisticated than a consumer borrower – regulation has been more “hands off” with regard to the terms commercial loans may contain. One such clause frequently found in commercial loan agreements is a confession of judgment clause, also called a cognovit judgment. A confession of judgment is written authorization by the borrower directing the entry of a judgment against him in the event he defaults on payment. A confession of judgment clause in a loan agreement permits the creditor on default to appear in court and confer judgment against the borrower.

Interestingly, Ohio is now considering legislation to regulate the use of the confession of judgment in a commercial loan agreement. House Bill 291 would require attorneys for creditors to include in a petition for confession of judgment the borrower’s last known address so that the borrower can be advised of the creditor’s decision to execute on the confession of judgment. Such notice gives the borrower the opportunity to dispute the execution on the confession of judgment clause. It would further provide that a confession of judgment be made “only for nonpayment of principal and interest under the terms of an instrument evidencing indebtedness,” which would eliminate the ability to obtain other damages. It also bans the use of the clause for something other than a nonmonetary default, which some Ohio courts have allowed. For example, in Fifth Third Bank v. Pezzo Construction, an Ohio appellate court allowed execution on a confession of judgment where the borrower failed to pay all taxes when due as required by the loan agreement. Another court rejected such use of confessions of judgment in Henry County Bank v. Stimmels, Inc. House Bill 291, if adopted, would make clear that only payment defaults can result on a confession of judgment.

Interestingly, Ohio is now considering legislation to regulate the use of the confession of judgment in a commercial loan agreement. House Bill 291 would require attorneys for creditors to include in a petition for confession of judgment the borrower’s last known address so that the borrower can be advised of the creditor’s decision to execute on the confession of judgment. Such notice gives the borrower the opportunity to dispute the execution on the confession of judgment clause. It would further provide that a confession of judgment be made “only for nonpayment of principal and interest under the terms of an instrument evidencing indebtedness,” which would eliminate the ability to obtain other damages. It also bans the use of the clause for something other than a nonmonetary default, which some Ohio courts have allowed. For example, in Fifth Third Bank v. Pezzo Construction, an Ohio appellate court allowed execution on a confession of judgment where the borrower failed to pay all taxes when due as required by the loan agreement. Another court rejected such use of confessions of judgment in Henry County Bank v. Stimmels, Inc. House Bill 291, if adopted, would make clear that only payment defaults can result on a confession of judgment.

House Bill 291 is not yet scheduled for a hearing.

Lending Club Class Action Lawsuit Predicated on Madden v Midland Risk

March 2, 2016UPDATE: This case is unrelated to another class action filed against Lending Club on April 6th

Lending Club is the latest publicly traded online lender to get hit by a shareholder class action lawsuit (OnDeck was first). Filed in the Superior Court of the State of California, plaintiff alleges in the complaint that Lending Club misleadingly concealed the fact that:

- Lending Club had an unsustainable business model that was predicated on it being able to issue loans with extremely high and/or usurious rates across the country

- that their loan investors would not be able to enforce the extremely high and/or usurious rates imposed by Lending Club because they violated state usury laws

- that without the extremely high and/or usurious rates, the loans generated through Lending Club’s marketplace would not be attractive to investors because the loans had very high credit risk and were subject to issues concerning insufficient documentation

- that a substantial portion of its loans were issued with rates in excess of those allowed by applicable state usury laws

The action seeks “recovery, including rescission, for innocent purchasers who suffered many millions of dollars in losses when the truth about Lending Club emerged and the its stock price plummeted.”

Among the Defendants is former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers.

The complaint alleges that the truth about Lending Club began to emerge after “the Second Circuit affirmed [in Madden v Midland] that the business model used by Lending Club was not valid because loans sold by banks to non-banks, third parties (such as Lending Club and its investors) are not exempt from state usury laws that limit interest rates.”

–In actuality, no such affirmation was made. Lending Club does not specifically use Midland Funding’s business model and the case was not about Lending Club, nor was Lending Club mentioned in it.

“Specifically, the Second Circuit observed that assignees and third-party debt buyers could not rely on the National Bank Act to export interest rates that were legal in one state but usurious in another, to the states where those rates were impermissible,” the complaint states.

–Perhaps, but Lending Club’s bank makes loans under the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, not the National Bank Act.

As supporting evidence, the complaint cites statements from Moody’s analysts, Morgan Stanley, Cross River Bank CEO Gilles Gade, and Lending Club CEO Renaud Laplanche himself in a quarterly earnings call.

While the impact of Madden v Midland has been seriously overblown, Lending Club’s stock has no doubt taken a beating since its IPO. The complaint states a loss of 43% from the original offering price. Among the defendants are:

- LendingClub Corporation

- Renaud Laplanche

- Carrie Dolan

- Daniel Ciporin

- Jeffrey Crowe

- Rebecca Lynn

- John J. Mack

- Mary Meeker

- John C. (Hans) Morris

- Lawrence Summers

- Simon Williams

- Morgan Stanley & Co. LLC

- Goldman, Sachs & Co.

- Credit Suisse Securities (USA) LLC

- Citigroup Global Markets Inc.

- Allen & Company LLC

- Stifel, Nicolaus & Company, Incorporated

- BMO Capital markets Corp.

- William Blair & Company, L.L.C.

- Wells Fargo Securities, LLC

NOTE: This case is unrelated to another class action filed against Lending Club on April 6th

Federal Usury Caps Unlikely After CFPB Statements

February 15, 2016 Business lenders and merchant cash advance companies can breathe a little earlier since David Silberman, the CFPB’s acting deputy director, said at a House hearing that federal usury caps were off the table for the nation’s most controversial form of lending, payday loans. “We will not establish a usury cap and interest-rate limits on these or any other lending product,” Silberman said. “We have not contemplated doing so and we will not do so.”

Business lenders and merchant cash advance companies can breathe a little earlier since David Silberman, the CFPB’s acting deputy director, said at a House hearing that federal usury caps were off the table for the nation’s most controversial form of lending, payday loans. “We will not establish a usury cap and interest-rate limits on these or any other lending product,” Silberman said. “We have not contemplated doing so and we will not do so.”

This should quell speculation that CFPB involvement or regulatory activity in other areas of lending, will eventually include interest rate caps at the federal level. The Dodd-Frank act actually bars the CFPB from setting rate caps but that hasn’t stopped lenders from thinking it might still happen otherwise.

Two years ago, Barney Frank, a co-sponsor of the Dodd-Frank act, said on the record that he himself was against federal interest rate caps when asked if they should exist in business lending.

Meanwhile, presidential candidate Bernie Sanders has proposed a nationwide usury cap of 15% APR. How exactly he would make that a reality, especially since it is unlikely to gain congressional popularity, is uncertain.

Court Refuses to Apply Federal Preemption to Loan Servicer Despite Bank’s Continued Interest in Loan

January 20, 2016 In November 2014, the Pennsylvania Office of Attorney General (“OAG”) filed a complaint against a number of companies that did business with a group of payday lenders. The payday lenders were a Delaware bank and three tribal entities. The defendants provided marketing services and operational support to the lenders and in some instances purchased portions of the loans. In its complaint, the OAG alleged that the defendants, and not the bank or tribes, were the de facto lenders and that their partnership with the bank and tribes were constructed to circumvent Pennsylvania usury laws.

In November 2014, the Pennsylvania Office of Attorney General (“OAG”) filed a complaint against a number of companies that did business with a group of payday lenders. The payday lenders were a Delaware bank and three tribal entities. The defendants provided marketing services and operational support to the lenders and in some instances purchased portions of the loans. In its complaint, the OAG alleged that the defendants, and not the bank or tribes, were the de facto lenders and that their partnership with the bank and tribes were constructed to circumvent Pennsylvania usury laws.

In their motions to dismiss, the defendants argued that, in regards to the loans issued by the Delaware bank, federal law preempted the OAG’s state usury claims. They explained that the Depository Institution Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (“DIDA”) allows state-charted federally insured banks to charge the same interest rate in any state as they are legally permitted to charge in the state in which they are located. The DIDA mirrors the language of section 85 of the NBA.

The defendants argued that because the Delaware bank was a state-charted federally insured bank, the DIDA preempted the causes of action in the OAG’s complaint as they pertained to the defendants’ partnership with the bank. As additional support for their preemption argument, the defendants highlighted the fact that the bank not only originated the loans but also retained them wholly, or at least in part.

Despite the bank’s origination and retention of the loans, the District court rejected the defendants’ arguments. It held that federal preemption only applied to the bank. In support of its holding, the court cited to the Third Circuit’s decision in In re Community Bank of Northern Virginia, 418 F.3d 277, 295 (3d Cir. 2005). In that case, the Circuit court held that state law claims against a non-bank were not preempted by the DIDA or the NBA.

The District court refused to apply federal preemption to the defendants even though the bank retained ownership of all or part of the loans. The court noted that the complaint alleged that the defendants, and not the bank, were the real parties in interest and therefore reasoned that preemption should not apply.

Pennsylvania v. Think Fin., Inc., 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4649 (D. Pa. 2016)

When it Comes to Usury Law, Be Careful What You Ask For

January 8, 2016 In a previous post, Creditor Fails to Navigate Usury Law “Minefield”, Ordered to Refund $1.3 Million to Debtor, I discussed a recent bankruptcy case in California. In the case, a lender had filed a claim in the borrower-debtor’s bankruptcy case. The debtor objected to the claim and brought a usury claim against the lender for allegedly usurious interest that it claimed it had paid.

In a previous post, Creditor Fails to Navigate Usury Law “Minefield”, Ordered to Refund $1.3 Million to Debtor, I discussed a recent bankruptcy case in California. In the case, a lender had filed a claim in the borrower-debtor’s bankruptcy case. The debtor objected to the claim and brought a usury claim against the lender for allegedly usurious interest that it claimed it had paid.

After a two day trial on the debtor’s objection to the lender’s bankruptcy claim, the court found in favor of the debtor and ordered the lender to refund the usurious interest it had charged the debtor. The court also ordered post-trial briefing on a number of issues, including:

Are the debtors barred by the two year statue of limitations on usury actions from recovering usurious interest paid prior to the 2 years before the date of the bankruptcy petition?

In its post-trial brief, the lender argued that the California statute of limitations provides that a borrower that commences an usury action against a lender may only recover the amount of usurious interest paid to the lender in the preceding two years prior to filing the complaint. Therefore, the lender argued, the amount that the debtor could recover should be limited to those payments that the debtor had made within the two years preceding the filing of the bankruptcy petition. The court disagreed.

The court first noted that California usury claims generally must be filed within two years of the payment at issue. However, if the lender brings an action on the debt, the borrower may cross complain for recovery of all usurious interest paid, regardless of the two year statute of limitations. The court found that this was also true where a lender files a claim for usurious interest in a bankruptcy proceeding. As support the court cited a recent ninth circuit which explained:

The filing of a proof of claim is analogous to filing a complaint in the bankruptcy case… And a claim objection by the debtor is analogous to an answer… In re Cruisephone, Inc., 278 B.R. 325, 330 (Bankr. E.D.N.Y. 2002) (“In the bankruptcy context, a proof of claim filed by a creditor is conceptually analogous to a civil complaint, an objection to the claim is akin to an answer or defense and an adversary proceeding initiated against the creditor that filed the proof of claim is like a counterclaim.”).

Based on the Ninth’s Circuit holding, the court found that the lender had “‘brought an action’ by filing its proof of claim and actively and aggressively pursuing its remedies in the course of the bankruptcy case, and the usury defenses and claims of the Debtors are in the nature of counterclaims, thus rendering the two-year statute of limitations inapplicable here.” As a result, the debtor was permitted to recover all of the usurious interest that the court had awarded it at trial.

In re Arce Riverside, LLC, 2015 Bankr. LEXIS 4380 (Bankr. D. Cal. 2015)

Getting a California Lender’s License

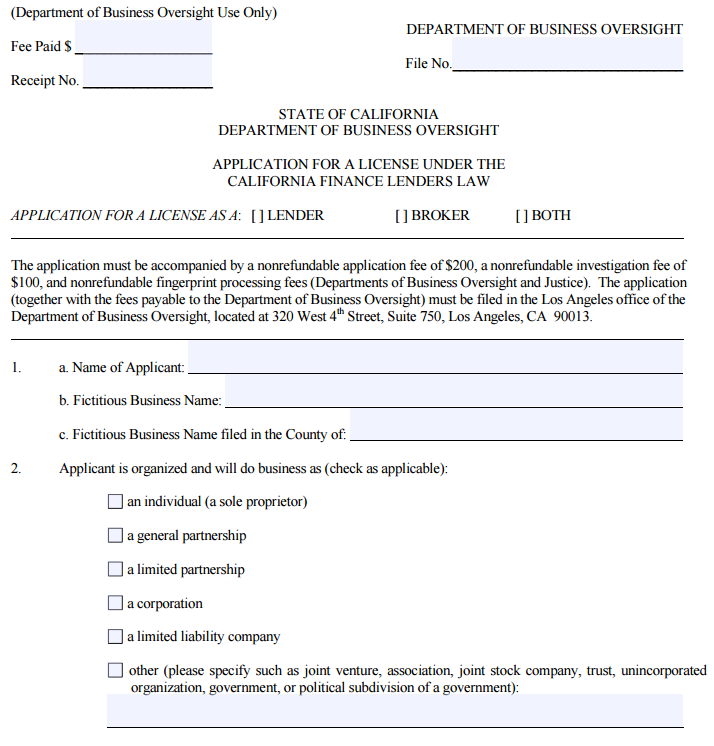

December 17, 2015Given the fact there have been a number of successful lawsuits against cash advance companies in California, many cash advance companies have decided to take a different route and get a lending license to provide loans to merchants in the state. If done correctly, this can allow companies to provide loans to merchants in California at roughly the same profit margins one could expect from a cash advance. Below I will discuss the process for obtaining a California lender’s license and some tips for making that process less painful.

To start, go to the California Department of Business Oversight and get the form titled “Application for a License Under the California Finance Lenders Law.” The application is long and detailed but don’t let that scare you. Most of the information you provide is really more related to letting the State know about your company and the main people that will be responsible for managing the lending operations. As you complete the form, one thing you do need to do is make sure you are very careful and meticulous as any small mistake will cause the application to be rejected making the process much longer.

To start, go to the California Department of Business Oversight and get the form titled “Application for a License Under the California Finance Lenders Law.” The application is long and detailed but don’t let that scare you. Most of the information you provide is really more related to letting the State know about your company and the main people that will be responsible for managing the lending operations. As you complete the form, one thing you do need to do is make sure you are very careful and meticulous as any small mistake will cause the application to be rejected making the process much longer.

The first part of the application requests basic information about your company and its officers. In filling out this and other parts of the application, it is essential to respond to all the questions. If you fail to miss just one response the application will be rejected. To that end, even if a question does not apply to you I find it better to respond “N/A” or “not applicable” rather than just leaving a blank. By doing that you force yourself to fill in every blank and therefore reduce the chances for missing a response resulting in a rejection of your application.

Also, you need to be very precise in your responses. I have experienced a situation where the examiner rejected an application because the name of the company was incorrectly spelled on the application. The name of the company was submitted on the application with “Inc” instead of the complete “Inc.” at the end of the company’s name. The examiners are very good at what they do and very thorough. You need to make sure the packet you submit is perfect and also that there are no inconsistencies in the document.

Another important point to remember is that the application requires you to name the person that will be responsible for running the location where the lending is occurring. The main requirement is that the person running the location must be physically present at the location. As a result, you could not manage a California office remotely from New York for instance. In another twist, if your principal location is out of state, you will need to get the license and fill out the main application for that out of state address. For the California location, you will need to fill out the short form application in addition to the main application and submit the short form application as part of the packet to allow the license to apply to the location in the state of California.

There are a number of exhibits you also have to provide as part of the process. Some of them are simple like a balance sheet for the company. It is acceptable that the company is new and has little in the way of assets. You just have to make sure you attach a balance sheet and that it is prepared in compliance with generally accepted accounting principles. I have seen times when the balance sheet was rejected because there was no line items for liabilities for instance, even though the company was new and therefore had none. It is probably wise to engage your accountant to make sure you submit a balance sheet that complies with those guidelines.

You also have to get a surety bond in the amount of $25,000. There are readily available bonding companies that specialize in providing these bonds. In addition, you need some other exhibits like a statement of good standing for your company, authorization for financial disclosure, social security number (on a separate exhibit), organizational chart and a few other documents. As with the rest of the application the key is to make sure you include everything they are asking for exactly as requested.

The most involved exhibit is the “Statement of Identity and Questionnaire.” That exhibit has to be filled out for each owner, officer and manager listed on the application. It requests detailed information going back 10 years for each person for items like residence address and work history.

In addition, there are a series of questions on topics such as whether the person has been involved in lawsuits, had any licenses revoked or declared bankruptcy. Fingerprints are also taken as part of the process. This part of the application is trying to vet the various people working for the company to make sure they are suitable to be in the lending business.

Once you have all the documents prepared, you need to put them together in a packet to send off to the Department of Business Oversight to be reviewed. Again, I cannot overemphasize how important it is to completely and accurately answer the questions and put the packet together. You need to make sure things are in the proper order and complete. Triple check the application for errors and to make sure that packet is presented in the best manner possible. You also need to determine the amount of fees to submit with the application. Then, send the package by overnight delivery to make sure you have proof of delivery.

So what happens next? Well there is usually a bit of a wait. Typically it takes 3 months or more to get a reply. If you have done your homework, you might get lucky and successfully get your license on the first try. If there are any deficiencies, you will get a response letter from the State detailing the items that need to be corrected in the application and a time frame in which you have to respond or the application is abandoned.

On the first go round, you are usually given at least 2 months so you should have plenty of time. Digest the things they want and provide the required information. The deficiency letters are very detailed so it should be easy to make the requested changes. Resubmit the requested items and wait for the next response. It could be in the form of another deficiency letter but it could be an approval of the license. Just keep on trying until you are finally successful.

That’s it, you are finally a licensed lender in California! But that is where the fun begins. You are subject to many laws in California and audits by the State. To get the right to operate as a licensed lender, you need to make sure you prepare your application correctly. Once you have done that, you need to get all your loan documents drafted in compliance with California law. Make sure you have adequate experience and professional help to take on those tasks.

Can California Lenders Pay Referral Fees to Unlicensed Brokers?

December 15, 2015 A new California law is drawing attention to a much-misunderstood issue – whether California Finance Lenders can pay referral fees to unlicensed ISOs. Effective January 1, 2016, the answer is yes, but only for commercial loans with an annual percentage rate of less than 36% where the lender reviews documents to verify the borrower’s ability to repay. These restrictions benefit non-profit lenders making business development loans, and shut out their higher-cost commercial lender competitors from paying referral fees to unlicensed ISOs.

A new California law is drawing attention to a much-misunderstood issue – whether California Finance Lenders can pay referral fees to unlicensed ISOs. Effective January 1, 2016, the answer is yes, but only for commercial loans with an annual percentage rate of less than 36% where the lender reviews documents to verify the borrower’s ability to repay. These restrictions benefit non-profit lenders making business development loans, and shut out their higher-cost commercial lender competitors from paying referral fees to unlicensed ISOs.

Existing regulations under California’s Finance Lender’s Law (“CFLL”) prohibit paying any compensation to unlicensed persons or companies for “soliciting or accepting applications for loans.” 10 CCR 1451(c). This prohibition does not apply to referrals for merchant cash advances or referrals to banks, which are not subject to the CFLL. A number of not-for-profit CFLL lenders offering business development loans complained that it was unfair that they could not pay referral fees to an unlicensed ISO while their higher-cost competitors, the merchant cash advance companies, could.

California SB 197, supported by Opportunity Fund, California’s largest not-for-profit commercial lender, and the California Association of Micro-Enterprise Organizations, a group of more than 170 organizations, agencies, and individuals dedicated to furthering micro-business development in California, aimed to remedy this perceived problem. According to an information sheet on SB 197 available on the Opportunity Fund’s web site:

Often, merchant advance companies offer less favorable terms to small businesses than commercial lenders; however, small businesses never learn about the commercial lenders that offer more favorable terms, because those lenders cannot compensate entities to refer business to them.

http://www.opportunityfund.org/media/blog/introducing-sb-197-(block)!/ (last accessed on December 9, 2015)

The legislature approved SB 197 and Gov. Jerry Brown signed it last October. Starting on January 1, 2016, a CFLL lender can pay a fee to an unlicensed person in connection with a referral of a prospective borrower if:

- The referral by the unlicensed person leads to the consummation of a commercial loan (defined as a loan with a principal amount of $5,000 or more the proceeds of which are intended by the borrower for use primarily for other than personal, family or household purposes);

- The loan contract provides for an annual percentage rate that does not exceed 36%; and

- Before approving the loan, the lender:

- Obtains documentation from the prospective borrower documenting the borrower’s commercial status. Examples of acceptable forms of documentation include, but are not limited to, a seller’s permit, business license, articles of incorporation, income tax returns showing business income, or bank account statements showing business income; and

- Performs underwriting and obtains documentation to ensure that the prospective borrower will have sufficient monthly gross revenue with which to repay the loan pursuant to the loan terms. The lender cannot make a loan if it determines through its underwriting that the prospective borrower’s total monthly expenses, including debt service payments on the loan for which the prospective borrower is being considered, will exceed the prospective borrower’s monthly gross revenue. Examples of acceptable forms of documentation for verifying current and projected gross monthly revenue and monthly expenses include, but are not limited to, tax returns, bank statements, merchant financial statements, business plans, business history, and industry-specific knowledge and experience. If the prospective borrower is a sole proprietor or a corporation and the loan will be secured by a personal guarantee provided by the owner, the lender must consider a credit report from at least one consumer credit reporting agency that compiles and maintains files on consumers on a nationwide basis.

The licensee must also maintain records of all compensation paid to unlicensed persons in connection with the referral of borrowers for a period of at least 4 years.

SB 197 also provides that a lender that pays compensation for a referral to an unlicensed person is liable for “any misrepresentation made to that borrower in connection with that loan.” It is not clear whether the lender is liable only for misrepresentations made by the unlicensed person who receives compensation for the referral, or if the regulator will interpret this provision more broadly. Further, lenders must provide such prospective borrowers this specific written statement in 10-point font or larger at the time the licensee receives an application for the loan:

You have been referred to us by [Name of Unlicensed Person]. If you are approved for the loan, we may pay a fee to [Name of Unlicensed Person] for the successful referral. [Licensee], and not [Name of Unlicensed Person] is the sole party authorized to offer a loan to you. You should ensure that you understand any loan offer we may extend to you before agreeing to the loan terms. If you wish to report a complaint about this loan transaction, you may contact the Department of Business Oversight at 1-866-ASK-CORP (1-866-275-2677), or file your complaint online at www.dbo.ca.gov.

Lenders must require prospective borrowers to acknowledge receipt of the statement in writing.

SB 197 defines “referral” to mean either the introduction of the borrower and the lender or the delivery to the lender of the borrower’s contact information. The following activities by an unlicensed person are not authorized:

- Participating in any loan negotiation;

- Counseling or advising the borrower about a loan;

- Participating in the preparation of any loan documents, including credit applications;

- Contacting the lender on behalf of the borrower other than to refer the borrower;

- Gathering loan documentation from the borrower or delivering the documentation to the lender;

- Communicating lending decisions or inquiries to the borrower;

- Participating in establishing any sales literature or marketing materials; and

- Obtaining the borrower’s signature on documents.

Many for-profit CFLL licensees may find the narrow exemption that permits CFLL licensees making commercial loans to accept referrals from non-licensed entities impractical. The industry may instead choose to focus on the existing prohibition against paying non-licensees for “soliciting or accepting applications for loans” to avoid the limitations on the loan terms.