Articles by Paul Sweeney

Gold Rush: Merchant Cash Advances Are Still Hot

August 18, 2019

Last year, when Kevin Frederick struck out on his own to form his own catering company in Annapolis, the veteran caterer knew that he’d need a food trailer for his business to succeed.

He reckoned that he had a good case for a $50,000 small-business loan. The Annapolis-based entrepreneur boasted stellar personal credit, $30,000 in the bank, and a track record that included 35 years of experience in his chosen profession. More impressively, his newly minted company—Chesapeake Celebrations Catering—was on a trajectory to haul in $350,000 in revenues over just eight months of operations in 2018. And, after paying himself a salary, he cleared $60,000 in pre-tax profit.

But Frederick’s business-credit profile was so thin that no bank or business funder would talk to him. So woeful was his lack of business credit, Frederick reports, that his only financing option was paying a broker a $2,000 finder’s fee for a high-interest loan.

Luckily, he says, everything changed when he discovered Nav, an online, credit-data aggregator and financial matchmaker.

Based in Utah, Nav had him spiff up his business credit with Dun & Bradstreet, a top rating agency and a Nav business partner. This was accomplished with a bankcard issued to Frederick’s business by megabank J.P. Morgan Chase. Soon afterward, he says, Nav steered him to Kapitus (formerly Strategic Funding Source), a New York-based lender and merchant cash advance firm that provided some $23,000 in funding.

“They led me in the right direction,” Frederick says of Nav. “A lady there (at Nav) helped me with my credit, warning me that the credit card I’d been using had an effect on my personal credit. Then she led me to Kapitus, all probably within a week.”

Now, Frederick has his food trailer. He reports that its total cost—$14,000 for the trailer, which came “with a concession window, mill-finished walls, and flooring” plus $43,000 in renovations—amounted to $57,000. Equipped with a full kitchen—including refrigeration, sinks, ovens, and a stove—the food trailer can be towed to weddings, reunions, and the myriad parties he caters in the Delmarva Peninsula. In addition, Frederick can also park the trailer at fairgrounds and serve seafood, barbeque, and other viands to the lucrative festival market.

Now, Frederick has his food trailer. He reports that its total cost—$14,000 for the trailer, which came “with a concession window, mill-finished walls, and flooring” plus $43,000 in renovations—amounted to $57,000. Equipped with a full kitchen—including refrigeration, sinks, ovens, and a stove—the food trailer can be towed to weddings, reunions, and the myriad parties he caters in the Delmarva Peninsula. In addition, Frederick can also park the trailer at fairgrounds and serve seafood, barbeque, and other viands to the lucrative festival market.

Meanwhile, the caterer’s funders are happy to have him as their new customer. The people at Kapitus, to whom he is making daily payments (not counting weekends and holidays), are especially grateful. “Nav provides a valuable service,” says Seth Broman, vice-president of business development at Kapitus. “They know how to turn coal into diamonds,”

Nav does not charge small businesses for its services. As it gathers data from credit reporting services with which it has partnerships—Experian, TransUnion, Dun and Bradstreet, Equifax—and employs additional metrics, such as cashflow gleaned from an entrepreneur’s bank accounts, Nav earns fees from credit card issuers, lenders and MCA firms.

The company has close ties to financial technology companies that include Kabbage and OnDeck, and also collaborates with MCA funders such as National Funding, Rapid Finance, FundBox, and Kapitus. “We give lenders and funders better-qualified merchants at a lower cost of client acquisition,” says Caton Hanson, Nav’s general counsel and co-founder, adding: “They don’t have to spend as much money on leads.”

As banks have increasingly shunned small-business lending in the decade since the financial crisis, and as the economy has snapped back with a prolonged recovery, alternative funders—particularly unlicensed companies offering lightly regulated, high-cost merchant cash advances (MCAs)—have been piling into the business.

And service companies like Nav—which is funded by nearly $100 million in venture capital and which reports aiding more than 500,000 small businesses since it was founded in 2012—are thriving alongside the booming alternative-funding industry.

Over the past five years, the MCA industry’s financings have been growing by 20% annually, according to 2016 projections by Bryant Park Capital, a Manhattan-based, boutique investment bank. BPC’s specialty finance division handles mergers and acquisitions as well as debt-and-equity capital raising across multiple industries and is one of the few Wall Street firms with an MCA-industry practice. By BPC’s estimates, the MCA industry will have more than doubled its small business funding to $19.2 billion by year- end 2019, up from $8.6 billion in 2014.

Bankrolled by a broad assortment of hedge funds, private equity firms, family offices, and assorted multimillionaire and billionaire investors on the qui vive for outsized returns on their liquid assets, the MCA industry promises a 20%-80% profit rate, reports David Roitblat, president of Better Accounting Solutions, a New York accountancy specializing in the MCA industry. Based on doing the books for some 30 MCA firms, Roitblat reports that the range in profit margins depends on the terms of contracts and a funder’s underwriting skills.

The numerical size and growth of the MCA industry is hard to ascertain, reports Sean Murray, editor of deBanked (this publication), which tracks trends in the industry and sponsors several major conferences. “So much is anecdotal,” Murray says.

Even so, the evidence that MCA companies are proliferating—and prospering—is undeniable. Over the past two years, deBanked’s events, which experience substantial attendance from the MCA industry, have consistently sold out, requiring the events to be moved to larger venues. In Miami, attendance in January this year topped 400-plus attendees, Murray reports, roughly double the crowd that packed the Gale Hotel in 2018.

Similarly, the May, 2019, Broker Fair in New York at the Roosevelt Hotel drew more than 700 participants compared with the sellout crowd of roughly 400 last year in Brooklyn. (Despite ample notice that this year’s Broker Fair at the Roosevelt was sold out and advance tickets were required, as many as 40-50 latecomers sought entry and, unfortunately, had to be turned away.)

The upsurge of capital and the swelling number of entrants into the MCA business has all the earmarks of a gold rush. “Everybody and his brother is trying to get a piece of the action,” asserts Roitblat, the New York accountant.

And there are two ways to hit paydirt in a gold rush. One way is to prospect for gold. But another way is to sell picks and shovels, tents, food, and supplies to the prospectors. “If you can find a way to service the gold rush, you can make a lot of money,” says Kathryn Rudie Harrigan, a management professor and business-strategy expert at the Columbia University Graduate School of Business. “It’s like profiteering in wartime.”

And there are two ways to hit paydirt in a gold rush. One way is to prospect for gold. But another way is to sell picks and shovels, tents, food, and supplies to the prospectors. “If you can find a way to service the gold rush, you can make a lot of money,” says Kathryn Rudie Harrigan, a management professor and business-strategy expert at the Columbia University Graduate School of Business. “It’s like profiteering in wartime.”

As Professor Harrigan suggests, cashing in on the gold rush by servicing it has parallels across multiple industries. Consider the case of Charles River Laboratories, which has capitalized on the rapid development of the biotechnology industry over the past few decades.

As scientists searched for biologics to battle diseases like cancer and AIDS, the Boston-area company began producing experimental animals known as “transgenic mice.” Informally known as “smart mice,” Charles River’s test animals are specially designed to carry human genes, aiding investigators in their understanding of gene function and genetic responses to diseases and therapeutic interventions. (The smart mouse’s antibodies can also be harvested. “Seven out of the eleven monoclonal antibody drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration between 2006 and 2011,” according to biotechnology.com, “were derived from transgenic mice.”)

In the MCA version of the gold rush, a bevy of law and accounting firms, debt-collection agencies and credit-approval firms, among other service providers, have either sprung to life to undergird the new breed of alternative funder or added expertise to suit the industry’s wants and needs. (This cohort has been joined, moreover, by a superstructure of Washington, D.C.-based trade associations and lobbyists that have been growing like expansion teams in a professional sports league. But their story will have to wait for another day.)

Rather than being exploitative, supporting companies serve as a vital mainstay in an industry’s ecosystem, notes Alfred Watkins, a former World Bank economist and Washington, D.C.-based consultant: “A gold miner can’t mine,” he says, “unless he has a tent and a pickaxe.”

And in the high-risk, high-reward MCA industry, which can have significant default rates depending on the risk model, many funders can’t fund if they don’t have reliable debt collection. Many of the bigger companies, says Paul Boxer, who works on the funding side of the industry, have the capability of collecting on their own. But for many others—particularly the smaller players in the industry—it’s necessary to hire an outside firm.

One of the more widely known collectors for the MCA industry is Kearns, Brinen & Monaghan where Mark LeFevre is president and chief executive. The Dover (Del.)- based firm, LeFevre says, first added MCA funders to its client roster in 2012; but it has only been since 2014 that “business really took off.”

LeFevre won’t say just how many MCA firms have contracted with him, but he estimates that his firm has scaled up its staff 35%-40% over the past five years to meet the additional MCA workload. The industry, LeFevre adds, “is one of the top-growth industries I’ve seen in the 36 years that I’ve been in business.”

He also says, “People in the MCA industry know a lot about where to put money, but collections are not one of their strong points. They need to get a professional. It gives them the free time to make more money while we go in behind them and collect.”

If repeated dunning fails to elicit a satisfactory response, KBM has several collection strategies that strengthen its hand. The big three, LeFevre says, are “negotiation, identifying assets, and litigation.” He adds: “We have a huge database of attorneys who do nothing but file suit on commercial debt internationally. Then we can enforce a judgment. You don’t want someone who just makes a few phone calls.”

Because business has become so competitive, LeFevre says, he won’t discuss his fee schedule. As to KBM’s success rate, he says no tidy figure is available either, but asserts: “Our checks sent to our clients are more than most agencies because of our proprietary collection process.”

Jordan Fein, chief executive at Greenbox Capital in Miami and a KBM client told deBanked: “We work with them. They’re organized and communicate well and they know to collect. They’re on the expensive side, though. I’ve got other agencies that I use that are cheaper.”

Debt-collection firm Merel Corp, a spinoff from the Tamir Law Group in New York, might be a lower-cost alternative. Formed in just the past 18 months to service the growing MCA industry, Merel typically takes 15%-25% of whatever “obligation” it can collect, says Levi Ainsworth, co-chief operating officer.

A successful collection, Ainsworth asserts, really begins with the underwriting process and attention to detail by the funders. “Instead of coming in at the end,” he says, “we try to prevent problems at the start of the process.”

For an MCA firm dealing with an excessive number of defaults, Merel sometimes places one of its employees with the funder to handle “pre-defaults,” for which it charges a lower fee. The collections firm has also built a reputation for not relying on a “confession of judgment.” Now that COJs have been outlawed for out-of-state collections in New York State, Merel’s skills could be more in demand.

Better Accounting Solutions, which has its offices on Wall Street, is another service-provider promising to lighten the workload of MCA firms by providing back-office support. The company is headed by Roitblat, a 36-year- old former rabbinical student turned tax-and-accounting entrepreneur. Since he founded the company with two part-time employees in 2011, it’s ballooned to some 70 employees.

Roitblat does not have all of his firm’s eggs in one MCA basket. His firm handles tax, accounting and bookkeeping work for law firms, the fashion industry, restaurants and architectural firms. Even so, he says, thirty MCA clients— or more than half his clientele—rely on the firm’s expertise, three of whom were just added in June. His best month was January, 2018, when six funders contracted for his services. “Growth in the MCA industry has been explosive,” he says.

MCA accounting work has its own vagaries and oddities. For example, because of the industry’s high default rate, Roitblat notes, a 10%-slice of every merchant’s payment is funneled into a “default reserve account.” And when an actual default occurs, credits are moved from the receivables account to the default reserve account.

Roitblat takes pride that his firm’s MCA work has passed audits from respected accounting firms like Friedman, Cohen, Taubman and Marcum LLP. Moreover, he has helped clients uncover internal fraud and, in one instance, spotted costly flaws in a business model. An early MCA client, Roitblat says, had no idea that “he was losing close to $100,000 a month by spending on Google ads.”

Better Accounting also keeps its rates low. The firm typically assigns a junior accountant to handle clients’ accounts while a senior manager oversees his or her work. “He (Roitblat) does a fantastic job,” says David Lax, managing partner of Orange Advance, a Lakewood (N.J.)-based MCA firm. “They understand the MCA business. And even if your business is small, they can set up the infrastructure and do the work more economically and efficiently than you can. You’d have to create the position of comptroller or senior-level accountant,” Lax adds, “to equal their work.”

Top-notch competence and low rates, Lax says, are not the only reasons he often refers Roitblat’s firm to fellow MCA companies. “The only thing better than their work,” he says, “is the people themselves.”

Whether it’s oil and gas, banking and real estate, construction, health care or high-technology—you name it—lawyers have an important role across nearly every industry. So too with the MCA industry where, as has been shown, there is an especially high demand for attorneys skilled at winning debt-collection cases.

To hear Greenbox’s Fein tell it, a skilled lawyer handling debt collection can write his or her own ticket. A talented attorney, he says, not only retrieves lost money and prevents losses, but enables the funder to “offer the product cheaper than the competition.

“We use a ton of attorneys in 35 states in the U.S. and in Canada,” Fein adds, “and you have no idea how many attorneys we go through until we find a good one.”

Until recently, much of the MCA industry’s success has resulted from a hands-off, laissez faire legal and regulatory environment—particularly the legal interpretation that a merchant cash advance is not a loan. The industry has also benefited from the fact that most credit regulation focused on consumer credit and not on business and commercial financings.

But now, as the MCA industry is maturing and showing up on the radar screens of state legislatures, Congress, regulatory agencies, and the courts, there is heightening demand for legal counsel. In just the past 12 months, California passed a truth-in-lending statute requiring MCA firms not only to clearly state their terms, but to translate the short-term funding costs of MCAs into an annual percentage rate. The state of New York, as has been noted, passed legislation restricting the use of COJs.

Moreover, notes Mark Dabertin, special counsel at Pepper Hamilton, a top national law firm based in Philadelphia, the state of New Jersey is contemplating licensing MCA practitioners. The Minnesota Court of Appeals recently determined in Anderson v. Koch that, because of a “call provision” in a funding contract, a merchant cash advance was actually a loan.

And, Dabertin warns, the Federal Trade Commission, which has the authority to treat a merchant cash advance as a consumer transaction—replete with the full panoply of consumer disclosures and protections—is training its gunsights on the industry. “On May 23,” Dabertin reports in a memo to clients, “the FTC launched an investigation into potentially unfair or deceptive practices in the small business financing industry, including by merchant cash advance providers.”

These pressures from government and the courts will only make doing business more costly and drive up the industry’s barriers to entry. Failing to stay legal, moreover, could not only result in punitive court judgments, but render an MCA firm vulnerable to legal action by their investors.

“It’s inevitable that the industry will evolve,” Dabertin says, and firms in the industry will have to self-police. “They will need to hire counsel and a compliance staff,” he adds. “You can’t just do it by the seat of your pants.”

Are The Bankers Taking Over Fintech?

June 27, 2019

For Rochelle Gorey, the chief executive and co-founder of SpringFour, a “social impact” fintech company, mingling with industry movers and shakers at this year’s LendIt Fintech Conference was just what the doctor ordered. “I went mainly for the networking opportunities,” Gorey told deBanked.

SpringFour, which is headquartered in Chicago, works with banks and financial institutions in the 50 states to get distressed borrowers back on track with their debt payments. It does this by digitally linking debtors with governmental and nonprofit agencies that promote “financial wellness.

The indebted parties—more than a million of whom had referrals that were arranged by Gorey’s tech-savvy company last year—constitute not only household consumers but also commercial borrowers. “Small businesses face the same issues of cash flow as consumers, and their business and personal income are often combined,” she says. “If their financial situation is precarious, it’s super-hard to get credit, a line of credit, or a business loan.”

Although Gorey felt “overwhelmed” at first by the throng of 4,000 conference-goers at Moscone Center West in San Francisco—roughly the same number as attended last year, conference organizers assert— her trepidation was short-lived. It wasn’t too long before she was in circulation and having chance encounters and serendipitous interactions, she says, with “all the right people at the workshops and at the tables in the Expo Hall.”

Although Gorey felt “overwhelmed” at first by the throng of 4,000 conference-goers at Moscone Center West in San Francisco—roughly the same number as attended last year, conference organizers assert— her trepidation was short-lived. It wasn’t too long before she was in circulation and having chance encounters and serendipitous interactions, she says, with “all the right people at the workshops and at the tables in the Expo Hall.”

Armed, moreover, with a “networking app” on her mobile phone, Gorey was able to arrange targeted meetings, scoring roughly a dozen, 15-minute tete-a-tetes during the two-day breakout sessions. These included audiences with community bankers, financial technology companies, and “small-dollar” lenders. “And it went both ways,” she says. “I had people reaching out to me”—just about everyone, it seemed, appeared receptive to “finding ways to boost their customers’ financial health.”

Gorey’s success at networking was precisely the experience that the event’s planners had envisioned, says Peter Renton, chairman and co-founder of the LendIt Fintech Conference. Organizers took pains to make schmoozing one of the key features of this year’s gathering. Not only did LendIt provide attendees with a bespoke networking app, but planners scheduled extra time for meet-ups. “We had around 10,000 meetings set up by the app,” Renton says, “about double the number of last year.”

deBanked did not attend the LendIt USA conference on the West Coast this year. But the publication sought out more than a half-dozen attendees—including several financial technology executives, a leading venture capitalist, a regulatory law expert, and the conference’s top administrators—to gather their impressions. While informal and manifestly unscientific, their responses nonetheless yielded up several salient themes.

The popularity—and effectiveness—of networking was a key takeaway. Most seized the opportunity to rub elbows with influential industry players, learn about the hottest startups, compare notes, and catch up on the state of the industry. Most importantly, the event presented a golden opportunity to make the introductions and connections that could generate dealmaking.

“My goal this year was to strike more partnerships with lenders and fintech companies,” says Levi King, chief executive and co-founder at Utah-based Nav, an online, credit-data aggregator and financial matchmaker for small businesses. “We had great meetings with Fiserv, Amazon, Clover Network (a division of First Data), and MasterCard,” he reports, rattling off the names of prominent financial services companies and fintech platforms.

James Garvey, co-founder and chief executive at Self Lender, an Austin-based fintech that builds creditworthiness for “thin file” consumers who have little or no credit history, said his goal at the conference was both to serve on a panel and “meet as many people as I could.”

Self Lender is in its growth stage following a $10 million, series B round of financing in late 2018 from Altos Ventures and Silverton Partners. Garvey reports having meetings with Bank of America and venture capitalist FTV Capital “over coffee” as well as F-Prime Capital, another venture capitalist. “It’s just about building a relationship,” he said of making connections, “so that at some point, if I’m raising money or want to partner, I can make a deal.”

There was a concerted effort to recognize women, as evidenced by a packed “Women in Fintech” (WIF) luncheon that drew roughly 250 persons, 95% of whom were women. (“Many men are big supporters of women in fintech and we didn’t want to exclude them,” Renton says). The luncheon was preceded by a novel event—a 30-minute, ladies-only “speed-networking” session—which attracted 160 participants, reports Joy Schwartz, president of LendIt Fintech and manager of the women’s programs.

At the luncheon, SpringFour’s Gorey says, “it was empowering just to see lot of women who are senior leaders working in financial services, banks and fintechs.” The keynote speech by Valerie Kay, chief capital officer at Lending Club, was another highlight. “She (Kay) talked about taking risks and going to a fintech startup after 23 years at Morgan Stanley,” Gorey reports, adding: “It was inspiring.”

The women’s luncheon also marked the launch of LendIt’s Women In Fintech mentor program, and presentation of a “Fintech Woman of the Year” award. The recipient was Luvleen Sidhu, president, co-founder and chief strategy officer at BankMobile, a digital division of Customers Bank, based near Philadelphia, which employs 250 persons and boasts two million checking account customers.

I am honored to be the 2019 Fintech Women of the Year and thrilled that @BankMobile won Most Innovative Bank. It’s very exciting to be recognized by @LendIt Fintech with this prestigious award and I congratulate the finalists in all the categories. https://t.co/qjADuKEMrB pic.twitter.com/hFJVFw1fLS

— Luvleen Sidhu (@LuvleenSidhu) April 11, 2019

BankMobile, which also won LendIt’s “Most Innovative Bank” award, has an alliance with Upstart to do consumer lending and a partnership with telecommunications company T-Mobile. Known as T-Mobile Money, the latter service provides T-Mobile customers with access to checking accounts with no minimum balance, no monthly or overdraft fees, and access to 55,000 automated teller machines, also with no fees. (At its website, T-Mobile Money describes itself as a bank and uses the slogan: “Not another bank, a better one.”)

The impressive salute to women notwithstanding, their ranks remained fairly thin: just 733 attendees identified themselves as “female” on their registration forms, LendIt’s Schwartz says, a little more than 18% of total participants. Seventy-five of the 350 total speakers and panelists—or 21%—were female. (Schwartz also reports that another 157 registrants selected “prefer not to say” as their sexual orientation, while 22 checked the box describing themselves as “non-conforming.”)

In LendIt’s defense, deBanked, who caters to a similar audience, regularly reviews its readership demographics using several tools. They have consistently indicated that women make up 18% – 23% of the total, in line with what LendIt experienced at its most recent event.

By all accounts, many panels were informative, jampacked and attendees were engaged. King, who moderated a panel on regulatory changes in small business lending, which dealt with such topics as California’s commercial “truth-in-lending” law and controversial “confessions of judgment” laws, says: “They didn’t have to lock the door but the room was pretty full and people seemed to be paying attention. I didn’t see people studying their cellphones.”

The Expo Hall was teeming with budding fintech entrepreneurs, financial services companies and multiple vendors hawking their wares. But as numerous fintechs were angling to forge lucrative symbiotic relationships with banks, some participants—even those who were hailing the conference for its networking and deal-making opportunities—lamented the heavy presence of the establishment.

The banks’ ubiquitousness especially vexed Matthew Burton, a partner at QED Investors, an Arlington, (Va.)-based, venture capital firm and a veteran fintech entrepreneur. Before signing on with QED last year, Burton had been the co-founder of Orchard Platform, an online technology and analytics vendor for fintech and financial services companies which was purchased by fintech lender Kabbage.

Not only did bankers seem to playing a more prominent role at the LendIt conference, Burton notes, but “big four” accounting firm Deloitte had signed on as a major sponsor. “The energy level seemed a bit lower than in past years,” Burton told deBanked. “It’s not like people were depressed but it wasn’t bubbling with excitement. A couple of years ago we thought all these new fintechs would replace the banks,” he explains. “Now the discussion is over how to partner and collaborate with banks. It’s not as exciting as when everyone thought banks were dinosaurs.

“I couldn’t really tell if there were more bankers attending this year,” Burton adds, “but it sure felt like it.”

King, the Nav executive, told deBanked: “It was a little bit subdued. I don’t know if it was nervousness about the economy or politics, but the subject of risk came up more often in side conversations with venture-backed businesses and banks and alternative fintech lenders. One large bank we deal with,” he adds, “told me it’s spending most of its time working on risk.”

Cornelius Hurley, a Boston University law professor and executive director of the Online Lending Policy Institute who participated in a standing-room-only session on state and federal fintech regulation, declares: “I’ve been to three of their conferences, including one in New York, and I would say that this one did not have as much pizzazz. It may be that the industry is maturing.”

For his part—when asked whether there was a palpable absence of passion this year—LendIt’s Renton told deBanked: “I would say that it felt more businesslike. Fintech has had a lot of hype and we have had conferences that were ridiculously over-hyped in 2015 and 2016. And in 2017 (the mood) was much more somber. This one felt optimistic and businesslike.”

There were 750 bankers in attendance, almost one in five participants. “The number of bankers was not up significantly” over last year, Renton says, “but the seniority of the bankers was higher. We worked very hard to get senior bankers to attend this year.”

Renton was bullish on the closer ties developing between nonbank online lenders and banks. That was reflected as well in the several panels exploring ways to develop partnerships between the two sides. He noted that a session called “How Banks are Matching Fintechs on Speed of Funding and User Experience” drew a heavy crowd. “It brought more bankers than we’ve ever had before,” Renton says.

Moderated by Brock Blake, founder and chief executive at the fintech Lendio, the panel was composed of three bankers: Ben Oltman, the Philadelphia-area head of digital lending and partnerships at Citizens Bank; Gina Taylor Cotter, a senior vice-president at American Express (the highest-ranking woman at the company); and Thomas Ferro, a senior marketing manager at Bank of America. “The banks came to LendIt not just to learn but to decide whom they’re going to partner with,” Renton says. “Fintechs need banks and banks need fintechs. That is the narrative you hear on both sides.”

(Asked whether any banks sponsored this year’s conference, Renton replied: “They are not sponsoring yet in any number but we are working on that.”)

OnDeck, a top-tier fintech lender to small-businesses in the U.S., which has been making forays abroad to Australian and Canadian markets, is an enthusiastic champion of the fintech-bank union. So much so that it claimed LendIt’s “Most Promising Partnership” award for the cooperative relationship it struck with Pittsburgh-based PNC Bank, which uses OnDeck’s platform to make small business loans. (Among the partnerships that OnDeck-PNC beat out: Gorey’s SpringFour, which was named a finalist in the competition for its association with BMO Harris Bank.)

“We were the first fintech lender to strike a true platform relationship with a bank,” Jim Larkin, head of corporate communications at OnDeck says, noting that the PNC deal follows on the New York-based fintech’s similar, innovative arrangement with J.P. Morgan Chase. “Others may do referrals,” he explains. “What we do is actually provide the underlying platform to accelerate a bank’s online lending capabilities. We deliver the software and expertise to construct the right type of online lending engine.”

Meanwhile, there was avid interest about the stock performance of publicly traded fintechs—for example, Square and GreenSky—both of which had seen their share prices tumble and then recover.

Burton noted that, among venture-backed firms, the most excitement seemed to be coming from Latin America. “Everyone was very bullish on a Mexican company, Credijusto, an alternative small business lender that was written up the in the Wall Street Journal,” he says. “It’s not going public yet but it had a large debt-and-equity raise of $100 million from Goldman Sachs. And SoftBank Group announced a $5 billion Latin American tech fund.

“There was a lot of talk,” he adds, “about how money was flowing into Mexico and Brazil.”

Online Loans You Can Take To The Bank

April 16, 2019

OnDeck, the reigning king of small business lending among U.S. financial technology companies, is sharpening its business strategies. Among its new initiatives: the company is launching an equipment-finance product this year, targeting loans of $5,000 to $100,000 with two-to-five year maturities secured by “essential-use equipment.”

In touting the program to Wall Street analysts in February, OnDeck’s chief executive, Noah Breslow, declared that the $35 billion, equipment-finance market is “cumbersome” and he pronounced the sector “ripe for disruption.”

While those performance expectations may prove true – the first results of OnDeck’s product launch won’t be seen until 2020 – Breslow’s message seemed to conflict with OnDeck’s image as a public company. Rather than casting itself as a disruptor these days, OnDeck emphasizes the ways that its business is melding with mainstream commerce and finance.

Consider that the New York-based company, which saw its year-over-year revenues rise 14% to $398.4 million in 2018, is collaborating with Visa and Ingo Money to launch an “Instant Funding” line-of-credit that funnels cash “in seconds” to business customers via their debit cards. With the acquisition of Evolocity Financial Group, it is also expanding its commercial lending business in Canada, a move that follows its foray into Australia where, the company reports, loan-origination grew by 80% in 2018.

Consider that the New York-based company, which saw its year-over-year revenues rise 14% to $398.4 million in 2018, is collaborating with Visa and Ingo Money to launch an “Instant Funding” line-of-credit that funnels cash “in seconds” to business customers via their debit cards. With the acquisition of Evolocity Financial Group, it is also expanding its commercial lending business in Canada, a move that follows its foray into Australia where, the company reports, loan-origination grew by 80% in 2018.

Perhaps most significant was the 2018 deal that OnDeck inked with PNC Bank, the sixth-largest financial institution in the U.S. with $370.5 billion in assets. Under the agreement, the Pittsburgh-based bank will utilize OnDeck’s digital platform for its small business lending programs. Coming on top of a similar arrangement with megabank J.P. Morgan Chase, the country’s largest with $2.2 trillion in assets, the PNC deal “suggests a further validation of OnDeck’s underlying technology and innovation,” asserts Wall Street analyst Eric Wasserstrom, who follows specialty finance for investment bank UBS.

“It also reflects the fact that doing a partnership is a better business model for the big banks than building out their own platforms,” he says. “Both banks (PNC and J.P. Morgan) have chosen the middle ground: instead of building out their own technology or buying a fintech company, they’ll rent.

“J.P. Morgan has a loan portfolio of $1 trillion,” Wasserstrom explains. “It can’t earn any money making loans of $15,000 or $20,000. Even if it charged 1,000 percent interest for those loans,” he went on, “do you know how much that will influence their balance sheet? How many dollars do think they are going to earn? A giant zero!”

“J.P. Morgan has a loan portfolio of $1 trillion,” Wasserstrom explains. “It can’t earn any money making loans of $15,000 or $20,000. Even if it charged 1,000 percent interest for those loans,” he went on, “do you know how much that will influence their balance sheet? How many dollars do think they are going to earn? A giant zero!”

Similarly, Wasserstrom says, spending the tens of millions of dollars required to develop the state-of-the art technology and expertise that would enable a behemoth like J.P. Morgan or a super-regional like PNC to match a fintech’s capability “would still not be a big needle-mover. You’d never earn that money back. But by partnering with a fintech like OnDeck,” he adds, “banks like J.P Morgan and PNC get incremental dollars they wouldn’t otherwise have.”

The alliance between OnDeck and old-line financial institutions is one more sign, if one more sign were needed, that commercial fintech lenders are increasingly blending into the established financial ecosystem.

Not so long ago companies like OnDeck, Kabbage, PayPal, Square, Fundation, Lending Club, and Credibly were viewed by traditional commercial banks and Wall Street as upstart arrivistes. Some may still bear the reputation as disruptors as they continue using their technological prowess to carve out niche funding areas that banks often neglect or disdain.

Yet many fintechs are forming alliances with the same financial institutions they once challenged, helping revitalize them with new product offerings. Other financial technology companies have bulked up in size and are becoming indistinguishable from any major corporation.

Big Fintechs are securitizing their loans with global investment banks, accessing capital from mainline financial institutions like J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo, and finding additional ways — including becoming publicly listed on the stock exchanges – to tap into the equity and debt markets.

One example of the maturation process: through mid-2018, Atlanta-based Kabbage has securitized $1.5 billion in two bond issuances, 30% of its $5 billion in small business loan originations since 2008.

One example of the maturation process: through mid-2018, Atlanta-based Kabbage has securitized $1.5 billion in two bond issuances, 30% of its $5 billion in small business loan originations since 2008.

In addition, fintechs have been raising their industry’s profile with legislators and regulators in both state and federal government, as well as with customers and the public through such trade associations as the Internet Lending Platform Association and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Both individually and through the trade groups, these companies are building goodwill by supporting truth-in-lending laws in California and elsewhere, promoting best practices and codes of conduct, and engaging in corporate philanthropy.

Rather than challenging the established order, S&P Global Market Intelligence recently noted in a 2018 report, this cohort of Big Fintech is increasingly burrowing into it. This can especially be seen in the alliances between fintech commercial lenders and banks.

“Bank channel lenders arguably have the best of both worlds,” Nimayi Dixit, a research analyst at S&P Global Market Intelligence wrote approvingly in a 2018 report. “They can export credit risk to bank partners while avoiding the liquidity risks of most marketplace lending platforms. Instead of disrupting banks, bank channel lenders help (existing banks) compete with other digital lenders by providing a similar customer experience.”

It’s a trend that will only accelerate. “We expect more digital lenders to incorporate this funding model into their businesses via white-label or branded services to banking institutions,” the S&P report adds.

Forming partnerships with banks and diversifying into new product areas is not a luxury but a necessity for Fundation, says Sam Graziano, chief executive at the Reston (Va.)-based platform. “You can’t be a one-trick pony,” he says, promising more product launches this year.

Fundation has been steadily making a name for itself by collaborating with independent and regional banks that utilize its platform to make small business loans under $150,000. In January, the company announced formation of a partnership with Bank of California in which the West Coast bank will use Fundation’s platform to offer a digital line of credit for small businesses on its website.

Fundation lists as many as 20 banks as partners, including most prominently a pair of tech-savvy financial institutions — Citizens Bank in Providence, R.I. and Provident Bank in Iselin, N.J. — which have been featured in the trade press for their enthusiastic embrace of Fundation.

Fundation lists as many as 20 banks as partners, including most prominently a pair of tech-savvy financial institutions — Citizens Bank in Providence, R.I. and Provident Bank in Iselin, N.J. — which have been featured in the trade press for their enthusiastic embrace of Fundation.

John Kamin, executive vice president at $9.8 billion Provident reports that the bank’s “competency” is making commercial loans in the “millions of dollars” and that it had generally shunned making loans as meager as $150,000, never mind smaller ones. But using Fundation’s platform, which automates and streamlines the loan-approval process, the bank can lend cheaply and quickly to entrepreneurs. “We’re able to do it in a matter of days, not weeks,” he marvels.

Not only can a prospective commercial borrower upload tax returns, bank statements and other paperwork, Kamin says, “but with the advanced technology that’s built in, customers can provide a link to their bank account and we can look at cash flows and do other innovative things so you don’t have to wait around for the mail.”

Provident reserves the right to be selective about which loans it wants to maintain on its books. “We can take the cream of the crop” and leave the remainder with Fundation, the banker explains. “We have the ability to turn that dial.”

The partnership offers additional side benefits. “A lot of folks who have signed up (for loans) are non-customers and now we have the ability to market to them,” he says. “After we get a small business to take out a loan, we hope that we can get deposits and even personal accounts. It gives us someone else to market to.”

As a digital lender, Provident can now contend mano a mano with another well-known competitor: J.P. Morgan Chase. “This is the perfect model for us,” says Kamin, “it gives us scale. You can’t build a program like this from scratch. Now we can compete with the big guys. We can compete with J.P. Morgan.”

For Fundation, which booked a half-billion dollars in small business loans last year, doing business with heavily regulated banks puts its stamp on the company. It means, for example, that Fundation must take pains to conform to the industry’s rigid norms governing compliance and information security. But that also builds trust and can result in client referrals for loans that don’t fit a bank’s profile. “For a bank to outsource operations to us,” Graziano says, “we have to operate like a bank.”

Bankrolled with a $100 million line of credit from Goldman Sachs, Fundation’s interest rate charges are not as steep as many competitors’. “The average cost of our loans is in the mid-to-high teens and that’s one reason why banks are willing to work with us,” Graziano says. “Our loans,” he adds, “are attractively structured with low fees and coupon rates that are not too dramatically different from where banks are. We also don’t take as much risk as many in the (alternative funding) industry.”

Despite its establishment ties, Graziano says, Fundation will not become a public company anytime soon. “Going public is not in our near-term plans,” he told deBanked. Doing business as a public company “provides liquidity to shareholders and the ability to use stock as an acquisition tool and for employees’ compensation,” he concedes. “But you’re subject to the relentlessly short-term focus of the market and you’re in the public eye, which can hurt long-term value creation.”

Graziano reports, however, that Fundation will be securitizing portions of its loan portfolio by yearend 2020.

PayPal Working Capital, a division of PayPal Holdings based in San Jose, and Square Inc. of San Francisco, are two Big Fintechs that branched into commercial lending from the payments side of fintech. PayPal began making small business loans in 2013 while Square got into the game in 2014. In just the last half-decade, both companies have leveraged their technological expertise, massive data collections, data-mining skills, and catbird-seat positions in the marketplace to burst on the scene as powerhouse small business lenders.

PayPal Working Capital, a division of PayPal Holdings based in San Jose, and Square Inc. of San Francisco, are two Big Fintechs that branched into commercial lending from the payments side of fintech. PayPal began making small business loans in 2013 while Square got into the game in 2014. In just the last half-decade, both companies have leveraged their technological expertise, massive data collections, data-mining skills, and catbird-seat positions in the marketplace to burst on the scene as powerhouse small business lenders.

With somewhat similar business models, the pair have also surfaced as head-to-head competitors, their stock prices and rivalry drawing regular commentary from investors, analysts and journalists. Both have direct access to millions of potential customers. Both have the ability to use “machine learning” to reckon the creditworthiness of business borrowers. Both use algorithms to decide the size and terms of a loan.

Loan approval — or denials — are largely based on a customer’s sales and payments history. Money can appear, sometimes almost magically in minutes, in a borrower’s bank account, debit card or e-wallet. PayPal and Square Capital also deduct repayments directly from a borrower’s credit or debit card sales in “financing structures similar to merchant cash advances,” notes S&P.

At its website, here is how PayPal explains its loan-making process. “The lender reviews your PayPal account history to determine your loan amount. If approved, your maximum loan amount can be up to 35% of the sales your business processed through PayPal in the past 12 months, and no more than $125,000 for your first two loans. After you’ve completed your first two loans, the maximum loan amount increases to $200,000.”

PayPal, which reports having 267 million global accounts, was adroitly positioned when it commenced making small business loans in 2013. But what has really given the Big Fintech a boost, notes Levi King, chief executive and co-founder at Utah-based Nav — an online, credit-data aggregator and financial matchmaker for small businesses – was PayPal’s 2017 acquisition of Swift Financial. The deal not only added 20,000 new business borrowers to its 120,000, reported TechCrunch, but provided PayPal with more sophisticated tools to evaluate borrowers and refine the size and terms of its loans.

“PayPal had already been incredibly successful using transactional data obtained through PayPal accounts,” King told deBanked, “but they were limited by not having a broad view of risk.” It was upon the acquisition of Swift, however, that PayPal gained access to a “bigger financial envelope including personal credit, business credit, and checking account information,” King says, adding: “The additional data makes it way easier for PayPal to assess risk and offer not just bigger loans, but multiple types of loans with various payback terms.”

While PayPal used the Swift acquisition to spur growth and build market share, its rival Square — which is best known for its point-of-sale terminals, its smartphone “Cash App,” and its Square Card — has employed a different strategy.

OF A FREIGHT TRAIN

By selling off loans to third-party institutional investors, who snap them up on what Square calls a “forward-flow basis,” the Big Fintech barged into small business lending with the subtlety of a freight train. In just four years, Square originated 650,000 loans worth $4.0 billion, a stunning rise from the modest base of $13.6 million in 2014.

Square’s third-party funding model, moreover, demonstrates the benefits afforded from being deeply immersed in the financial ecosystem. Off-loading the loans “significantly increases the speed with which we can scale services and allows us to mitigate our balance sheet and liquidity risk,” the company reported in its most recent 10K filing.

Square’s third-party funding model, moreover, demonstrates the benefits afforded from being deeply immersed in the financial ecosystem. Off-loading the loans “significantly increases the speed with which we can scale services and allows us to mitigate our balance sheet and liquidity risk,” the company reported in its most recent 10K filing.

Square does not publicly disclose the entire roster of its third-party investors. But Kim Sampson, a media relations manager at Square, told deBanked that the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board — “a global investment manager with more than CA$300 billion in assets under management and a focus on sustained, long term returns” – is one important loan-purchaser.

Square also offers loans on its “partnership platform” to businesses for whom it does not process payments. And late last year the company introduced an updated version of an old-fashioned department store loan. Known as “Square Installments,” the program allows a merchant to offer customers a monthly payment plan for big-ticket purchases costing between $250 and $10,000.

Which model is superior? PayPal’s — which retains small business loans on its balance sheet — or Square’s third-party investor program? “The short answer,” says UBS analyst Wasserstrom, “is that PayPal retains small business loans on its balance sheet, and therefore benefits from the interest income, but takes the associated credit and funding risk.”

Meanwhile, as PayPal and Square stake out territory in the marketplace, their rivalry poses a formidable challenge to other competitors.

Both are well capitalized and risk-averse. PayPal, which reported $4.23 billion in revenues in 2018, a 13% increase over the previous year, reports sitting on $3.8 billion in retained earnings. Square, whose 2018 revenues were up 51 percent to $3.3 billion, reported that — despite losses — it held cash and liquid investments of $1.638 billion at the end of December.

King, the Nav executive, observes that Able, Dealstruck, and Bond Street – three once-promising and innovative fintechs that focused on small business lending – were derailed when they could not overcome the double-whammy of high acquisition costs and pricey capital.

“None of them were able to scale up fast enough in the marketplace,” notes King. “The process of institutionalization is pushing out smaller players.”

Get The Affidavit or Waive It? Examining Confessions of Judgment

February 1, 2019 Caton Hanson, the chief legal officer and co-founder of the online credit-reporting and business-to-business matchmaker Nav, says that his Salt Lake City-based company would not associate with a small-business financier that included “confessions of judgment” in its credit contracts.

Caton Hanson, the chief legal officer and co-founder of the online credit-reporting and business-to-business matchmaker Nav, says that his Salt Lake City-based company would not associate with a small-business financier that included “confessions of judgment” in its credit contracts.

“If we understood that any of our merchant cash advance partners were using confessions of judgment as a means to enforce contracts,” Hanson told deBanked, “we would view that as abusive and distance ourselves from those partners. As a venture-backed company,” Hanson adds, “we have some significant investors, including Goldman Sachs, and I’m sure they would support us.”

Steve Denis, executive director of the Small Business Finance Association, which represents companies in the merchant cash advance (MCA) industry, says that, as an organization, “We’ve taken a strong stance against confessions of judgment.”

He reports that his Washington, D.C.-based trade group is prepared to work with legislators and policy-makers of any political party, regulators, business groups and the news media “to ban that type of practice.

“We’re fighting against the image that we’re payday lenders for business,” Denis says of the merchant cash advance industry. “We’re trying to figure out internally what we can do to stop that from happening and we have been speaking to members of Congress and their staff.”

“Confessions of judgment,” says Cornelius Hurley, a law professor at Boston University and executive director of the Online Lending Policy Institute, “are to the merchant cash advance industry what mandatory arbitration is to banks. Neither enforcement device reflects well on the firms that use them.”

These are just some of the reactions from members of the alternative lending and financial technology community to a blistering series of articles published by Bloomberg News on the use—and alleged misuse—of confessions of judgment (COJs) by merchant cash advance companies. The series charges the MCA industry with gulling unwary small businesses by not only charging high interest rates for quick cash but of using confession-laden contracts to seize their assets without due process.

The Bloomberg articles also reported that it doesn’t matter in which state the small business debtors reside. By bringing legal action in New York State courts, MCA companies have been able to use enforcement powers granted by the confessions to collect an estimated $1.5 billion from some 25,000 businesses since 2012.

“I don’t think anyone can read that series of articles and honestly say what went on were good practices and in the best interest of small business,” says SBFA’s Denis, noting that none of the companies cited in the Bloomberg series belonged to his trade group. “It’s shocking to see some companies in our space doing things we’d classify as predatory,” he adds. “As an industry we’re becoming more sophisticated, but there are still some bad actors out there.”

A confession of judgment is a hand-me-down to U.S. jurisprudence from old English law. The term’s quaint, almost religious phrasing evokes images of drafty buildings, bleak London fog, and dowdy barristers in powdered wigs and solemn black gowns. (And perhaps debtor prisons as well.)

A confession of judgment is a hand-me-down to U.S. jurisprudence from old English law. The term’s quaint, almost religious phrasing evokes images of drafty buildings, bleak London fog, and dowdy barristers in powdered wigs and solemn black gowns. (And perhaps debtor prisons as well.)

Yet while the legal provision’s wings have been clipped—the Federal Trade Commission banned the use of confessions of judgment in consumer credit transactions in 1985 and many states prohibit their use outright or in such cases as residential real estate contracts—COJs remain alive and well in many U.S. jurisdictions for commercial credit transactions.

Even so, most states where COJs are in use, such as California and Pennsylvania, have adopted safeguards. Here’s how the San Francisco law firm Stimmel, Stimmel and Smith describes a COJ.

“A confession of judgment is a private admission by the defendant to liability for a debt without having a trial. It is essentially a contract—or a clause with such a provision—in which the defendant agrees to let the plaintiff enter a judgment against him or her. The courts have held that such a process constitutes the defendant’s waiving vital constitutional rights, such as the right to due process, thus (the courts) have imposed strict requirements in order to have the confession of judgment enforceable.”

In California, those “strict requirements” include not only that a written statement be “signed and verified by the defendant under oath,” but that it must be accompanied by an independent attorney’s “declaration.” If no independent attorney signs the declaration or—worse still—the plaintiff’s attorney signs the document, the confession is invalid.

But if the confession is “properly executed,” the plaintiff is entitled to use the full panoply of tools for collection of the judgment, including “writs of execution” and “attachment of wages and assets.”

In Pennsylvania, confessions of judgment are nearly as commonplace as Philadelphia Eagles’ and Pittsburgh Steelers’ fans, particularly in commercial real estate transactions. Says attorney Michael G. Louis, a partner at Philadelphia-area law firm Macelree Harvey, “They may go back to old English law, but if you get a business loan or commercial lease in Pennsylvania, a confession of judgment will be in there. It’s illegal in Pennsylvania for a consumer loan or residential real estate. But unless it’s a national tenant with a ton of bargaining power—a big anchor store and the owner of the shopping center really wants them—95% of commercial leasing contracts have them.

In Pennsylvania, confessions of judgment are nearly as commonplace as Philadelphia Eagles’ and Pittsburgh Steelers’ fans, particularly in commercial real estate transactions. Says attorney Michael G. Louis, a partner at Philadelphia-area law firm Macelree Harvey, “They may go back to old English law, but if you get a business loan or commercial lease in Pennsylvania, a confession of judgment will be in there. It’s illegal in Pennsylvania for a consumer loan or residential real estate. But unless it’s a national tenant with a ton of bargaining power—a big anchor store and the owner of the shopping center really wants them—95% of commercial leasing contracts have them.

“And any commercial bank in Pennsylvania worth its salt includes them in their commercial loan documents,” Louis adds.

Pennsylvania’s laws governing COJs contain a number of additional safeguards. For example, the confession of judgment is part of the note, guaranty or lease agreement—not a separate document—but must be written in capital letters and highlighted. One of the defenses that used to be raised against COJs, Louis says, was that a contractual document was written in fine print “but we haven’t seen fine print for years.”

Other reforms in Pennsylvania have come about, moreover, as a result of a 1994 case known as “Jordan v. Fox Rothschild.” Says Louis: “It used to be lot worse. You used to be able to file a confession of judgment and levy on a defendant’s bank account before he knew what happened. It was brutal. But after the Fox Rothschild case, they changed the law to prevent taking away a defendant’s right of notice and the opportunity to be heard.”

Because of that case, which takes its name from the Fox Rothschild law firm and involved a dispute between a Philadelphia landlord renting commercial space to Jordan, a tenant, the law governing COJs in Pennsylvania requires, among other things, a 30-day notice before a creditor or landlord can execute on the confession. During that period the defendant has the opportunity to stay the execution or re-open the case for trial.

Defenses against the execution of a COJ can entail arguments that creditors failed to comply with the proper language or procedures in drafting the document. But the most successful argument, Louis says, is a “factual defense.” Louis cites the case of a retail clothing store renting space in a shopping center that has a leaky roof. In the 30-day notice period after the landlord invoked the confession of judgment, the tenant was able to demonstrate to the court that he had asked the landlord “ten times” to fix the roof before spending the rent money on roof repairs. In such a case, the courts will grant the defendant a new trial but, Louis says, the parties typically reach a settlement. “Banks generally will waive a jury trial,” he notes, “because they don’t want to take a chance of getting hammered by a jury.”

Defenses against the execution of a COJ can entail arguments that creditors failed to comply with the proper language or procedures in drafting the document. But the most successful argument, Louis says, is a “factual defense.” Louis cites the case of a retail clothing store renting space in a shopping center that has a leaky roof. In the 30-day notice period after the landlord invoked the confession of judgment, the tenant was able to demonstrate to the court that he had asked the landlord “ten times” to fix the roof before spending the rent money on roof repairs. In such a case, the courts will grant the defendant a new trial but, Louis says, the parties typically reach a settlement. “Banks generally will waive a jury trial,” he notes, “because they don’t want to take a chance of getting hammered by a jury.”

A number of states, including Florida and Massachusetts ban the use of confessions of judgment. That’s one big reason that Miami attorney Roger Slade, a partner at Haber Law, advises clients that “there’s no place like home.” In other words: commercial contracts should specify that any legal disputes will be adjudicated in Florida. “It’s like having home field advantage in the NFL playoffs,” Slade remarked to deBanked. “You don’t want to play on someone else’s turf.”

He has also been warning Floridians for several years against the way that COJs were treated by New York courts. Writing in the blog, “The Florida Litigator,” Slade—a native New Yorker who is certified to practice law there as well as in Florida counseled in 2012: “If you live in New York, a creditor can have your client sign a confession of judgment and, in the event of a default on a loan, can march directly to the courthouse and have a final judgment entered by the clerk. That’s right—no complaint, no summons, no time to answer, no two-page motion to dismiss. The creditor gets to go right for the jugular.”

In addition, because of the “full faith and credit clause of the U.S. Constitution,” Slade notes in an interview, a contract that’s enforced by the New York courts must be honored in Florida. “Courts in Florida have no choice,” Slade says. “It’s a brutal system and it’s unfortunate.”

In December, two U.S. senators from opposing parties—Ohio Democrat Sherrod Brown and Florida Republican Marco Rubio—introduced bipartisan legislation to amend both the Federal Trade Commission Act and Truth in Lending Act to do away with COJs. Their legislative proposal reads:

“(N)o creditor may directly or indirectly take or receive from a borrower an obligation that constitutes or contains a congnovit or confession of judgment (for purposes other than executory process in the State of Louisiana), warrant of attorney, or other waiver of the right to notice and the opportunity to be heard in the event of suit or process theron.”

But with a dysfunctional and divided federal government, warring power factions in Washington, and an influential financial industry, there’s no telling how the legislation will fare. Meantime, the New York State attorney general’s office announced in December that it will investigate the use of COJs following the Bloomberg series. And New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has declared support for legislation that will, among other things, prohibit the use of confessions in judgment for small business credit contracts under $250,000 and restrict judgments by New York courts to in-state parties.

But if New York State or Congressional legislation are adopted it can have “unintended consequences” to merchant cash advance firms in the Empire State—and to their small business customers as well—asserts the general counsel for one MCA firm. “Losing the confession of judgment will be removing what little safety net there is in a risky industry,” the attorney says, noting that the industry has roughly a 15% default rate.

“It is not as powerful a tool as the Bloomberg news stories would have you believe,” this attorney, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told deBanked. “The suggestion seems to be that the MCAs can use the confession of judgment to get back the total amount of money due—and then some—while leaving a trail of dead bodies behind. But that’s not the case.

“What is much more likely to be the case,” he adds, “is that MCA companies try to get the defaulting merchant back on track. And—probably more than we should and only after we’ve tried to reach out to them and failed—do we then reluctantly use the COJ as a last resort. At which point we hope we can recover some part of our exposure. The numbers vary, but the losses are always in the thousands of dollars. These are not micro-transactions.

“What’s going to happen,” he concludes, “is that It will not make sense for us to work with those merchants most in need of working capital. The unfortunate reality is that businesses who don’t have collateral and can’t get a Small Business Administration product will be left out in the cold.”

All of which prompts BU professor Hurley to argue that the “Swiss cheese” system of financial regulation among the 50 states continues to be a root cause of regulatory confusion. Echoing Miami attorney Slade’s concern about New York courts’ dictating to Florida citizens, Hurley likens the situation governing COJs with the disorderly array of state laws governing usury regulations.

In the 1978 “Marquette” decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a Nebraska bank, First of Omaha, could issue credit cards in Minnesota and charge interest rates that exceeded the usury rate ceiling in the Gopher State. Since then, usury rates enacted by state legislatures have become virtually unenforceable.

“The problem we’re seeing with confessions of judgment is a subset of the usury situation,” Hurley says. “One state’s disharmony becomes a cancer on the whole system. It’s a throwback to Colonial times with 50 states each having their own jurisdictions—and it doesn’t work.”

Hurley’s Online Lending Policy Institute has joined with the Electronic Transactions Association and recruited a phalanx of “academics, non-banks, law firms and other trade associations as members or affiliates” to form the Fintech Harmonization Task Force. It is monitoring the efforts by the 50 states to align their regulatory oversight of the booming financial technology industry which was recently recommended by a U.S. Treasury report.

Hurley’s Online Lending Policy Institute has joined with the Electronic Transactions Association and recruited a phalanx of “academics, non-banks, law firms and other trade associations as members or affiliates” to form the Fintech Harmonization Task Force. It is monitoring the efforts by the 50 states to align their regulatory oversight of the booming financial technology industry which was recently recommended by a U.S. Treasury report.

Tom Ajamie, who practices law in New York and Houston and has won multimillion-dollar, blockbuster judgments against “dozens of financial institutions” including Wall Street investment firms, also argues for greater regulatory oversight. He urges greater funding and expansion of the powers of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to rein in “the anticipatory use” of confessions of judgment in commercial transactions.

However, notes Catherine Brennan, a partner at Hudson Cook in Baltimore, the job of protecting small businesses is outside the agency’s mandate. “The CFPB doesn’t have authority over commercial products as a general rule,” she explained in an interview. “Consumers are viewed as a vulnerable population in need of protections since the 1960’s.” As a society “we want protection for households because the consequences are high. A family could become homeless if they lose a house. Or (they) could lose employment if they lose a car and can’t drive. And there is also unequal bargaining power between lenders and consumers.

“Large institutions have lawyers to draft contracts and consumers have to agree on a take it or leave it basis. So there’s not a lot of negotiation and government has decided that consumers need protections, including a (Federal Trade Commission) ban on confessions of judgment.”

But Christopher Odinet, a law professor at the University of Oklahoma and a member of Hurley’s harmonization task force, sees the efforts of the federal government and the states to grapple with confessions of judgment as further recognition that small businesses have more in common with consumers than with big business. The COJ controversy follows on the recent passage of a commercial truth-in-lending bill by the State of California which, for the first time, stipulated that consumer-style disclosures should be included in business loans and financings under $500,000 made by non-bank financial organizations.

He cites the close-to-home example of an accomplished professional who got in over his head in financial dealings. “I recently observed a situation where a family member who is a very successful and affluent medical professional was relying on his own untrained business skills,” Odinet says. “He was about to enter into a sophisticated and complex business partnership relying on his intuition and general sense of confidence in the other party.”

Odinet says that he recommended that his relative hire a lawyer. Which, Odinet says, he did.

Less Than Perfect — New State Regulations

December 21, 2018

You could call California’s new disclosure law the “Son-in-Law Act.” It’s not what you’d hoped for—but it’ll have to do.

That’s pretty much the reaction of many in the alternative lending community to the recently enacted legislation, known as SB-1235, which Governor Jerry Brown signed into law in October. Aimed squarely at nonbank, commercial-finance companies, the law—which passed the California Legislature, 28-6 in the Senate and 72-3 in the Assembly, with bipartisan support—made the Golden State the first in the nation to adopt a consumer style, truth-in-lending act for commercial loans.

The law, which takes effect on Jan. 1, 2019, requires the providers of financial products to disclose fully the terms of small-business loans as well as other types of funding products, including equipment leasing, factoring, and merchant cash advances, or MCAs.

The financial disclosure law exempts depository institutions—such as banks and credit unions—as well as loans above $500,000. It also names the Department of Business Oversight (DBO) as the rulemaking and enforcement authority. Before a commercial financing can be concluded, the new law requires the following disclosures:

The financial disclosure law exempts depository institutions—such as banks and credit unions—as well as loans above $500,000. It also names the Department of Business Oversight (DBO) as the rulemaking and enforcement authority. Before a commercial financing can be concluded, the new law requires the following disclosures:

(1) An amount financed.

(2) The total dollar cost.

(3) The term or estimated term.

(4) The method, frequency, and amount of payments.

(5) A description of prepayment policies.

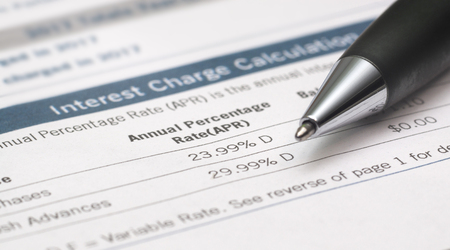

(6) The total cost of the financing expressed as an annualized rate.

The law is being hailed as a breakthrough by a broad range of interested parties in California—including nonprofits, consumer groups, and small-business organizations such as the National Federation of Independent Business. “SB-1235 takes our membership in the direction towards fairness, transparency, and predictability when making financial decisions,” says John Kabateck, state director for NFIB, which represents some 20,000 privately held California businesses.

“What our members want,” Kabateck adds, “is to create jobs, support their communities, and pursue entrepreneurial dreams without getting mired in a loan or financial structure they know nothing about.”

Backers of the law, reports Bloomberg Law, also included such financial technology companies as consumer lenders Funding Circle, LendingClub, Prosper, and SoFi.

But a significant segment of the nonbank commercial lending community has reservations about the California law, particularly the requirement that financings be expressed by an annualized interest rate (which is different from an annual percentage rate, or APR). “Taking consumer disclosure and annualized metrics and plopping them on top of commercial lending products is bad public policy,” argues P.J. Hoffman, director of regulatory affairs at the Electronic Transactions Association.

The ETA is a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing nearly 500 payments technology companies worldwide, including such recognizable names as American Express, Visa and MasterCard, PayPal and Capital One. “If you took out the annualized rate,” says ETA’s Hoffman, “we think the bill could have been a real victory for transparency.”

The ETA is a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing nearly 500 payments technology companies worldwide, including such recognizable names as American Express, Visa and MasterCard, PayPal and Capital One. “If you took out the annualized rate,” says ETA’s Hoffman, “we think the bill could have been a real victory for transparency.”

California’s legislation is taking place against a backdrop of a balkanized and fragmented regulatory system governing alternative commercial lenders and the fintech industry. This was recognized recently by the U.S. Treasury Department in a recently issued report entitled, “A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities: Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation.” In a key recommendation, the Treasury report called on the states to harmonize their regulatory systems.

As laudable as California’s effort to ensure greater transparency in commercial lending might be, it’s adding to the patchwork quilt of regulation at the state level, says Cornelius Hurley, a Boston University law professor and executive director of the Online Lending Policy Institute. “Now it’s every regulator for himself or herself,” he says.

Hurley is collaborating with Jason Oxman, executive director of ETA, Oklahoma University law professor Christopher Odinet, and others from the online-lending industry, the legal profession, and academia to form a task force to monitor the progress of regulatory harmonization.

For now, though, all eyes are on California to see what finally emerges as that state’s new disclosure law undergoes a rulemaking process at the DBO. Hoffman and others from industry contend that short-term, commercial financings are a completely different animal from consumer loans and are hoping the DBO won’t squeeze both into the same box.

Steve Denis, executive director of the Small Business Finance Association, which represents such alternative financial firms as Rapid Advance, Strategic Funding and Fora Financial, is not a big fan of SB-1235 but gives kudos to California solons—especially state Sen. Steve Glazer, a Democrat representing the Bay Area who sponsored the disclosure bill—for listening to all sides in the controversy. “Now, the DBO will have a comment period and our industry will be able to weigh in,” he notes.

While an annualized rate is a good measuring tool for longer-term, fixed-rate borrowings such as mortgages, credit cards and auto loans, many in the small-business financing community say, it’s not a great fit for commercial products. Rather than being used for purchasing consumer goods, travel and entertainment, the major function of business loans are to generate revenue.

A September, 2017, study of 750 small-business owners by Edelman Intelligence, which was commissioned by several trade groups including ETA and SBFA, found that the top three reasons businesses sought out loans were “location expansion” (50%), “managing cash flow” (45%) and “equipment purchases” (43%).

The proper metric to be employed for such expenditures, Hoffman says, should be the “total cost of capital.” In a broadsheet, Hoffman’s trade group makes this comparison between the total cost of capital of two loans, both for $10,000.

Loan A for $10,000 is modeled on a typical consumer borrowing. It’s a five-year note carrying an annual percentage rate of 19%—about the same interest rate as many credit cards—with a fixed monthly payment of $259.41. At the end of five years, the debtor will have repaid the $10,000 loan plus $5,564 in borrowing costs. The latter figure is the total cost of capital.

Compare that with Loan B. Also for $10,000, it’s a six month loan paid down in monthly payments of $1,915.67. The APR is 59%, slightly more than three times the APR of Loan A. Yet the total cost of capital is $1,500, a total cost of capital which is $4,064.33 less than that of Loan A.

Meanwhile, Hoffman notes, the business opting for Loan B is putting the money to work. He proposes the example of an Irish pub in San Francisco where the owner is expecting outsized demand over the upcoming St. Patrick’s Day. In the run-up to the bibulous, March 17 holiday, the pub’s owner contracts for a $10,000 merchant cash advance, agreeing to a $1,000 fee.

Once secured, the money is spent stocking up on Guinness, Harp and Jameson’s Irish whiskey, among other potent potables. To handle the anticipated crush, the proprietor might also hire temporary bartenders.

When St. Patrick’s Day finally rolls around—thanks to the bulked-up inventory and extra help—the barkeep rakes in $100,000 and, soon afterwards, forwards the funding provider a grand total of $11,000 in receivables. The example of the pub-owner’s ability to parlay a short-term financing into a big payday illustrates that “commercial products—where the borrower is looking for a return on investment—are significantly different from consumer loans,” Hoffman says.

SBFA’s Denis observes that financial products like merchant cash advances are structured so that the provider of capital receives a percentage of the business’s daily or weekly receivables. Not only does that not lend itself easily to an annualized rate but, if the food truck, beautician, or apothecary has a bad day at the office, so does the funding provider. “It’s almost like the funding provider is taking a ride” with the customer, says Denis.

SBFA’s Denis observes that financial products like merchant cash advances are structured so that the provider of capital receives a percentage of the business’s daily or weekly receivables. Not only does that not lend itself easily to an annualized rate but, if the food truck, beautician, or apothecary has a bad day at the office, so does the funding provider. “It’s almost like the funding provider is taking a ride” with the customer, says Denis.

Consider a cash advance made to a restaurant, for instance, that needs to remodel in order to retain customers. “An MCA is the purchase of future receivables,” Denis remarks, “and if the restaurant goes out of business— and there are no receivables—you’re out of luck.”

Still, the alternative commercial-lending industry is not speaking with one voice. The Innovative Lending Platform Association—which counts commercial lenders OnDeck, Kabbage and Lendio, among other leading fintech lenders, as members—initially opposed the bill, but then turned “neutral,” reports Scott Stewart, chief executive of ILPA. “We felt there were some problems with the language but are in favor of disclosure,” Stewart says.