Articles by Paul Sweeney

Gale Force Twins

April 24, 2018

As Hurricane Irma swept through the Caribbean and barreled toward the Florida Keys early last September, Wendy Vila, chief executive, at Unicus Capital evacuated her home in West Palm Beach and decamped to Panama City in the Florida panhandle where “it was just a little bit rainy.”

After safely waiting out Irma, she says, her return south was precarious. The roads were strewn with tree branches and other debris. Fuel was scarce. Many gas stations were either closed or posted signs reading “No Gas.” “Restaurants had run out of food,” Vila adds, “so there was nothing to eat” along the highway.

She returned to West Palm Beach but didn’t stay long. Instead, Vila again drove west, this time across the Florida peninsula to the South Florida city of Naples, not far from where Irma had made landfall. “I went there to volunteer with Samaritan’s Purse for two days,” she says, referring to the Boone, N.C.-based Christian organization that provides humanitarian aid to people in physical need. “Things were a lot worse there than in West Palm Beach,” she reports. “A lot of trees were down, houses were flooded and people had to throw all of their belongings out onto the street.”

Meanwhile, many of the Florida merchants whom Unicus funds were distressed. “If people had no power,” Vila says, “they couldn’t function. A lot of businesses had to close down. For some merchants in the affected areas,” she adds, Unicus extended “a 90-day grace period.”

Vila’s experience with Hurricane Irma – both professionally and personally — is not an isolated one. She is among several business lenders whom deBanked interviewed about the storm and its aftermath. This article grew out of deBanked’s Florida networking event at the Gale Hotel in South Beach in late January. We went back to many of the attendees as well as to other business-funders in The Sunshine State and sought out their experiences before, during and after the powerful tempest.

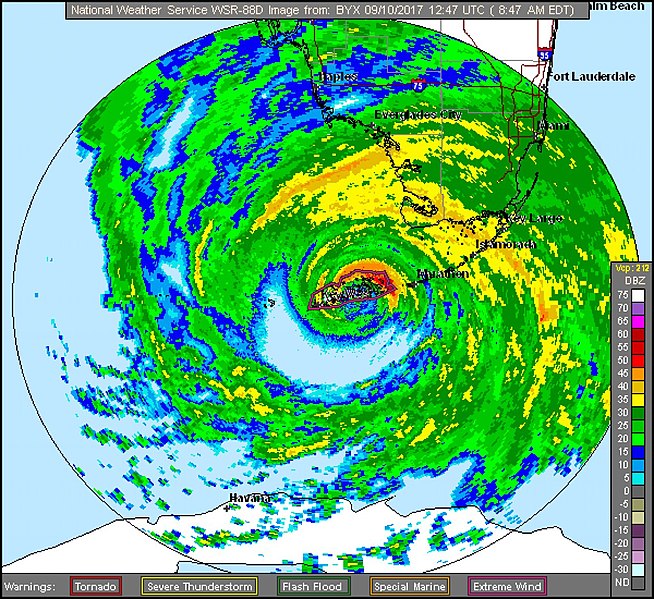

At one point, Hurricane Irma was the strongest hurricane ever recorded in the Atlantic by the National Hurricane Center. As Irma took dead aim at Florida, it packed sustained winds exceeding 157 miles per hour, earning it the designation of a Category 5 storm, the highest and most destructive. It slammed into the Florida Keys as a Category 4 hurricane, reached the Gulf of Mexico, and then came ashore a second time on Florida’s west coast at Marco Island, just south of Naples, and began traversing the state as a Category 3 hurricane, gradually losing strength. By the time Irma exited Florida, it had been downgraded to a tropical storm. According to the National Hurricane Center, Irma caused an estimated $50 billion in damage in the U.S., making it the fifth-costliest hurricane to hit the mainland.

Financiers and brokers told personal stories of working with and assisting merchants across Florida who sought to regain their lost footing and keep from going — literally — underwater. In many cases, members of the alternative business financing community said, they were simultaneously assisting troubled merchants while they themselves struggled with Irma-occasioned troubles that ranged from inconvenience to hardship.

“I was ten days without power,” says Manny Columbie, funding manager at Axiom Financial, based in South Miami. Columbie, who lives in the residential Westchester district of Miami, not far from the campus of Florida International University, says that he conducts much of his business from his home. That power loss not only constrained his ability to keep working but posed a life-or-death situation for his family: Columbie’s 90-year-old grandmother, who lives with him and his girlfriend, depends on electrical power to operate her oxygen pump.

Fortunately, he says, he had a backup generator, the use of which alternated between providing power for his grandmother’s oxygen and the family’s refrigerator. Meanwhile, his roof was leaking and there was six inches of rainwater swamping the house — the water gushing into the kitchen through the laundry room, dishwasher and even the oven.

Fortunately, he says, he had a backup generator, the use of which alternated between providing power for his grandmother’s oxygen and the family’s refrigerator. Meanwhile, his roof was leaking and there was six inches of rainwater swamping the house — the water gushing into the kitchen through the laundry room, dishwasher and even the oven.

While Columbie saw instances of tempers growing short in Miami’s September heat, he was nonetheless cheered by the way his community responded. “Neighbors were coming by to see if I needed gasoline for my generator,” Columbie says. “People were firing up food on their outside grills. There was no air-conditioning or cold showers but we cooled off by jumping in a neighbor’s pool. I saw a lot of people coming together.”

At the same time, he was doing what he could to assist merchants who did business with Axiom. Only one – a retail clothing store in Miami – was permanently shuttered. One of his clients, Oscar Pratt, owner of Odessy Party Supplies in Miami Gardens, was grateful for a moratorium on daily payments.

“We’re in the business of selling party accessories for events from births to funerals and everything in-between,” Pratt says. “Baby showers, christenings, birthdays, quinceaneras, ‘Sweet Sixteens,’ graduations, weddings, and all kinds of themed parties like Halloween,” he says. “We sell plates and cups, candy bags, cake-toppers, small favors, pinatas…”

Pratt said he’d called his funders ahead of the storm and “requested some leeway” from payments. Once the storm hit – and for two weeks afterward while there was no electricity – the party-supply business was pretty much on hold. “We had a few days without electricity or phone,” he says. “We couldn’t open the doors and do business because we use computer-generated receipts. Our customer base was down to just about nothing. Without electricity, people weren’t working and they weren’t having parties.”

Following the two-week grace period, Pratt says that his funders, which included QuarterSpot, granted a second two-week period of leniency in which Odessy was allowed to make reduced payments. “It was very difficult,” he says. “There was no help from FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) or from our insurance company since we’re on high ground and there were no physical damages, just the electricity.”

He reckoned that Odessy, which boasts annual revenues of $1.2 million, was deprived of roughly $50,000-$60,000 in sales because of Irma. Pratt reports that if his lenders had “played hardball” and demanded that he make his payments, he could have stayed in business thanks to “cash on hand” but it wouldn’t have been easy.

Meantime, his lenders’ forbearance was soon rewarded. By October, business was back to normal and he resumed making payments in full. “As soon as the lights went on,” Pratt says, “the parties started again.”

Similarly, says Paul Boxer, chief marketing officer at Quicksilver Capital in Brooklyn, the ultimate impact of Hurricane Irma on his firm’s funding business was to build trust and cement relationships with clients in South Florida. “We had a full team on board to answer the large number of calls coming in and to assist our merchants with any questions they had,” he says.

Many affected merchants, Boxer reports, were forced to evacuate ahead of the storm. When they returned, it was common for them to discover that their shops and stores sustained flooding damage from the heavy rains and a storm surge. Roofs were blown-off and structures were battered by 100-plus mile-an-hour winds, falling trees, and whipped-up debris. Even businesses that suffered little damage were paralyzed by the loss of electricity, impassable roads, and the absence of customers.

Many affected merchants, Boxer reports, were forced to evacuate ahead of the storm. When they returned, it was common for them to discover that their shops and stores sustained flooding damage from the heavy rains and a storm surge. Roofs were blown-off and structures were battered by 100-plus mile-an-hour winds, falling trees, and whipped-up debris. Even businesses that suffered little damage were paralyzed by the loss of electricity, impassable roads, and the absence of customers.

“Some were down for a few days,” Boxer reports. “Some were down a month to two months. We kept in touch. We were really on top of things with our merchants and asking them what they needed. We even fielded general safety questions and directed them on whom to call with insurance questions and other related business questions. It was good business,” he adds, “because it showed you cared. We were looking to do the right thing by our merchants and they appreciated it.”

Quicksilver typically offered merchants a two-to-three week “reprieve” on payments, Boxer says. For those businesses and entreprenuers whose operations were “completely out of commission” and needed more time, he says, the company suspended payments for as long as two months.

In the end, Quicksilver’s policy of forbearance reaped dividends. It not only built up good will with its customer base but also with the Independent Sales Organizations (ISOs) who’d brokered many of the firm’s Florida deals. “We helped grow that relationship,” Boxer says of the merchant-ISO connection. “They (ISOs) love getting renewals. It’s been a win-win for everybody.”

Doug Rovello, senior managing partner at Fund Simple, Inc., an alternative business lender and broker in Palm Harbor, a beach town just outside Tampa, says the Tampa-St. Petersburg area was spared from severe flooding but “we did experience power outages.” Among his clients, he reports, businesses in the food industry were among the most vulnerable. “I had one restaurant that lost $200,000 in business in the month of September,” he says.

When the electricity went down, grocery stores and bodegas, restaurants, bars, pizzerias, sub shops, delis and luncheonettes suffered outsized losses. Without power, businesses in the food industry were forced to dump spoiled meat, rotting fish, unusable dishes like appetizers and other foodstuffs requiring refrigeration.

When the electricity went down, grocery stores and bodegas, restaurants, bars, pizzerias, sub shops, delis and luncheonettes suffered outsized losses. Without power, businesses in the food industry were forced to dump spoiled meat, rotting fish, unusable dishes like appetizers and other foodstuffs requiring refrigeration.

Rovello reports that the hurricane managed to bollix up the business of one top client, a leading ticket broker in the area with a reputation for obtaining “exclusive” tickets to major events such as A-list rock concerts and featured sporting contests – including the Super Bowl. “He buys tickets in advance and when one big event was canceled he got stuck with $30,000 in tickets that he had to eat,” Rovello says.

Other kinds of businesses that depend on alternative lenders and got hit hard from the loss of power, Rovello observes, were medical clinics, doctors’ offices, pain-management centers, and assisted-living quarters – particularly those south of Sarasota. A number of golf courses also closed down for a couple of weeks, Rovello notes, further impairing the tourism and entertainment economy. “They were not allowed to move any of the damage that was done – poles, trees, et cetera until FEMA got there,” he says.

For some 30 days following Irma’s arrival, Rovello reports that he asked clients to make modest payments – perhaps $100 instead of a $750 monthly payment — “to keep their accounts active.” He also used his connections with FEMA adjusters and interceded with funders on behalf of clients– and even businesses that were not clients – who found themselves in arrears.

While many Floridians were seeking higher ground or hightailing it out of state, Jay Bhatt, who is a senior vice president of marketing at Breakout Capital in McLean, Va., was catching one of the last Jet Blue flights into Orlando to help out his aging parents. They are now in their late 60s and 70s, he reports, and living in a retirement community in Polk County, about ten miles south of Disney World.

Irma was still a Category 1 hurricane with 100 mph winds when it hit Orlando. The electrical grid went down, but Bhatt was able to purchase a generator – the kind designed specifically to provide electricity for oxygen respirators — from Home Depot. During his stay, Bhatt made several car trips in search of fuel, each of which took him probably 35-40 minutes. “We also leveraged some of the neighbors’ sockets,” he says, “but they were so small that the wattage only allowed for the operation of the fridge and a fan.”

Electricity was restored after four or five days. “The fact that it was a retirement community might have been why we got power back so soon while it took two or three weeks for many others,” he reckons.

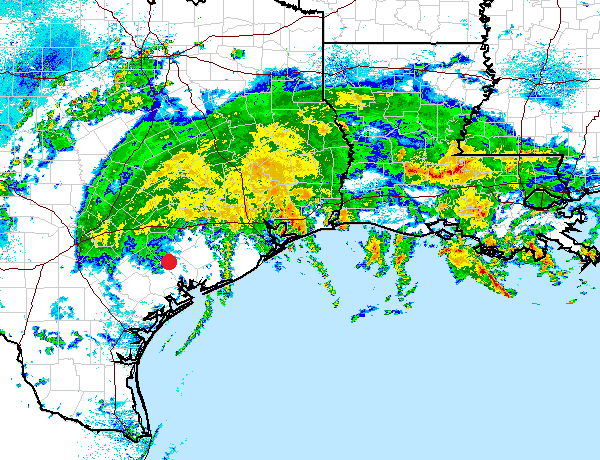

While Bhatt’s attention was focused on his parents, his employer – which had just offered a blanket hold on payments to its merchant accounts in 11 Texas counties that had been simultaneously inundated and walloped by Hurricane Harvey – now faced the challenge of responding to the second hurricane in two weeks. With Irma, Breakout chose to deal with its customers individually. “We didn’t do an immediate blanket response” as in Texas, Bhatt says, adding: “We were able to contact each one and we only wrote off one small business.”

While Bhatt’s attention was focused on his parents, his employer – which had just offered a blanket hold on payments to its merchant accounts in 11 Texas counties that had been simultaneously inundated and walloped by Hurricane Harvey – now faced the challenge of responding to the second hurricane in two weeks. With Irma, Breakout chose to deal with its customers individually. “We didn’t do an immediate blanket response” as in Texas, Bhatt says, adding: “We were able to contact each one and we only wrote off one small business.”

Rakem Lampkin, senior customer service representative at Pearl Capital, a New York-based alternative funder, says that his firm funds “roughly 175” businesses in South Florida. In addition to those establishments already mentioned as economically reeling because of Irma, such as restaurants, he cited “car dealerships, automotive repair shops and tech companies” as among the hardest hit, especially from the lack of electricity.

Lampkin also noted that many of Pearl’s merchants felt Irma’s wrath when colleges and state schools closed their doors. “Everything from transportation, lunches, sports equipment, even mom-and-pop florists” were slammed, he says, adding: “When the schools shut down, our payments slowed down.”

Pearl provided preferential treatment to merchants on the coast who were granted “a hold on debit payments,” Lampkin says. Even for coastal businesses that remained “structurally sound,” the business owners’ and employees’ “homes were affected, which kept them from getting to work,” he says.

As for businesses situated inland, “We were still sympathetic,” Lampkin says, but after an initial five-day grace-period their discounts were in the range of 66%-75% “so that we could focus our resources toward the people on the coast.”

To monitor the situation from New York, Lampkin says, the company was able to rely on accounts in the local news media, Google Maps, and other Internet sources. “We evaluated the situation case-by-case and week-by-week,” he says.

Jennifer Legg, a co-owner of Rochelle’s Jewelry & Watch Repair at the Indian River Mall in Vero Beach, is a Pearl-funded merchant who says she shut down the family-run business “for six or seven days” after Irma while the electricity went out. “Trees were down and a lot of people lost food and trailers, but we were not impacted as much as we were supposed to be,” she remarked.

Most of the shop’s business consists of customers stopping in for a new battery or a watch-band. Once they’re in the store, there’s a chance that they’ll purchase something else. But Irma put the kibosh on mall traffic. “A lot of people left the state, so that hurt business,” Legg says.

The store – which records annual sales of about $200,000 — lost probably $10,000 in revenue because of Irma. “It was very hard for that month of September,” Legg says. “Even after the doors opened, it was dead. No money came in for about two weeks.”

Fortunately, though, her capital source “did not take money out for a week,” she says. “If they’d kept taking it out,” she added, “we would have defaulted.”

The Madden Decision, Three Years Later

February 18, 2018

At first, reversing the 2015 Madden v. Midland Funding court decision, which continues to vex the country’s financial system and which is having a negative impact on the financial technology industry, seemed like a fairly reasonable expectation.

The controversial ruling by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York, which also covers the states of Connecticut and Vermont, had humble roots. Saliha Madden, a New Yorker, had contracted for a credit card offered by Bank of America that charged a 27% interest rate, which was both allowable under Delaware law and in force in her home state.

But when Madden defaulted on her payments and the debt was eventually transferred to Midland Funding, one of the country’s largest purchasers of unpaid debts, she sued on behalf of herself and others. Madden’s claim under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act was that the debt was illegal for two reasons: the 27% interest rate was in violation of New York State’s 16% civil usury rate and 25% criminal usury rate; and Midland, a debt-collection agency, did not have the same rights as a bank to override New York’s state usury laws.

In 2013, Madden lost at the district court level but, two years later, she won on appeal. Extension of the National Bank Act’s usury-rate preemption to third party debt-buyers like Midland, the Second Circuit Court ruled, would be an “overly broad” interpretation of the statute.

For the banking industry, the Madden decision – which after all involved the Bank of America — meant that they would be constrained from selling off their debt to non-bank second parties in just three states. But for the financial technology industry, says Todd Baker, a senior fellow Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and a principal at Broadmoor Consulting, it was especially troubling.

“The ability to ‘export’ interest rates is critical to the current securitization market and to the practice that some banks have embraced as lenders of record for fintechs that want to operate in all 50 states,” Baker told deBanked in an e-mail interview.

A 2016 study by a trio of law professors at Columbia, Stanford and Fordham found other consequences of Madden. They determined that “hundreds of loans (were) issued to borrowers with FICO scores below 640 in Connecticut and New York in the first half of 2015, but no such loans after July 2015.” In another finding, they reported: “Not only did lenders make smaller loans in these states post-Madden, but they also declined to issue loans to the higher-risk borrowers most likely to borrow above usury rates.”

With only three states observing the “Madden Rule,” the general assumption in business, financial and legal circles was that the Supreme Court would likely overturn Madden and harmonize the law. Brightening prospects for a Madden reversal by the Supremes: not only were all segments of the powerful financial industry behind that effort but the Obama Administration’s Solicitor General supported the anti-Madden petitioners (but complicating matters, the SG recommended against the High Court’s hearing the case until it was fully resolved in lower courts).

Despite all the heavyweight backing, however, the High Court announced in June, 2016, that it would decline to hear Madden.

That decision was especially disheartening for members of the financial technology community. “The Supreme Court has upheld the doctrine of ‘valid when made’ for a long time,” a glum Scott Stewart, chief executive of the Innovative Lending Platform Association – a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing small-business lenders including Kabbbage, OnDeck, and CAN Capital — told deBanked.

Even so, the setback was not regarded as fatal. Congress appeared poised to ride to the lending industry’s rescue. Indeed, there was rare bipartisan support on Capitol Hill for the Protecting Consumers’ Access to Credit Act of 2017 — better known as the “Madden fix.”

Introduced in the House by Patrick McHenry, a North Carolina Republican, and in the Senate by Mark Warner, Democrat of Virginia, the proposed legislation would add the following language to the National Bank Act. “A loan that is valid when made as to its maximum rate of interest…shall remain valid with respect to such rate regardless of whether the loan is subsequently sold, assigned, or otherwise transferred to a third party, and may be enforced by such third party notwithstanding any State law to the contrary.”

Just before Thanksgiving, the House Financial Services Committee approved the Madden fix by 42-17, with nine Democrats joining the Republican majority, including some members of the Congressional Black Caucus. Notes ILPA’s Stewart: “We were seeing broad-based support.”

But the optimism has been short-lived. The Madden fix was not included in a package of financial legislation recently approved by the Senate Banking Committee, headed by Sen. Mike Crapo, Republican of Idaho. Moreover, observes Stewart: “Senator Warner appears to have gotten cold feet.”

What happened? Last fall, a coast-to-coast alliance of 202 consumer groups and community organizations came out squarely against the McHenry-Warner bill. Denouncing the bill in a strongly worded public letter, the groups — ranging from grassroots councils like the West Virginia Citizen Action Group and the Indiana Institute for Working Families to Washington fixtures like Consumer Action and Consumer Federation of America – declared: “Reversing the Second Circuit’s decision, as this bill seeks to do, would make it easier for payday lenders, debt buyers, online lenders, fintech companies, and other companies to use ‘rent-a-bank’ arrangements to charge high rates on loans.”

The letter also charged that, if enacted, the McHenry-Warner bill “could open the floodgates to a wide range of predatory actors to make loans at 300% annual interest or higher.” And the group’s letter asserted that “the bill is a massive attack on state consumer protection laws.”

Lauren Saunders, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center in Washington, a signatory to the letter and spokesperson for the alliance, told deBanked that “our main concern is that interest-rate caps are the No. 1 protection against predatory lending and, for the most part, they only exist at the state level.”

But in their study on Madden, the Stanford-Columbia-Fordham legal scholars report that the strength of state usury laws has largely been sapped since the 1970s. “Despite their pervasiveness,” write law professors Colleen Honigsberg, Robert J. Jackson, Jr., and Richard Squire, “usury laws have very little effect on modern American lending markets. The reason is that federal law preempts state usury limits, rendering these caps inoperable for most loans.”

While the battle over the Madden fix has all the earmarks of a classic consumers-versus-industry kerfuffle, the fintechs and their allies are making the argument that they are being unfairly lumped in with payday lenders. “Online lending, generally at interest rates below 36%, is a far cry from predatory lending at rates in the hundreds of percent that use observable rent-a-charter techniques and that result in debt-traps for borrowers,” insists Cornelius Hurley, a Boston University law professor and executive director of the Online Lending Policy Institute. Because of fintechs, he adds: “A lot of people who wouldn’t otherwise qualify in the existing system are getting credit.”

A 2016 Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank study reports that traditional sources of funding for small businesses are gradually exiting that market. In 1997, small banks under $1 billion in assets –which are “the traditional go-to source of small business credit,” Fed researchers note — had 14 percent of their assets in small business loans. By 2016, that figure had dipped to about 11 percent.

The Joint Small Business Credit Survey Report conducted by the Federal Reserve in 2015 determined that the inability to gain access to credit “has been an important obstacle for smaller, younger, less profitable, and minority-owned businesses.” It looked at credit applications from very small businesses that depend on contractors — not employees – and discovered that only 29 percent of applicants received the full amount of their requested loan while 30 percent received only partial funding. The borrowers who “were not fully funded through the traditional channel have increasingly turned to online alternative lenders,” the Fed study reported.

The ILPA’s Stewart gives this example: A woman who owns a two-person hair-braiding shop in St. Louis and wants to borrow $20,000 to expand but has “a terrible credit score of 640 because she’s had cancer in the family,” will find the odds stacked against when seeking a loan from a traditional financial institution.

But a fintech lender like Kabbage or CAN Capital will not only make the loan, but often deliver the money in just a few days, compared with the weeks or even months of delivery time taken by a typical bank. “She’ll pay 40% APR or $2,100 (in interest) over six months,” Steward explains. “She’s saying, ‘I’ll make that bet on myself’ and add two additional chairs, which will give her $40,000-$50,000 or more in new revenues.”

In yet another analysis by the Philadelphia Fed published in 2017, researchers concluded that one prominent financial technology platform “played a role in filling the credit gap” for consumer loans. In examining data supplied by Lending Club, the researchers reported that, save for the first few years of its existence, the fintech’s “activities have been mainly in the areas in which there has been a decline in bank branches….More than 75 percent of newly originated loans in 2014 and 2015 were in the areas where bank branches declined in the local market.”

Meanwhile, there is palpable fear in the fintech world that, without a Madden fix, their business model is vulnerable. Those worries were exacerbated last year when the attorney general of Colorado cited Madden in alleging violations of Colorado’s Uniform Consumer Credit Code in separate complaints against Marlette Funding LLC and Avant of Colorado LLC. According to an analysis by Pepper Hamilton, a Philadelphia-headquartered law firm, “the respective complaints filed against Marlette and Avant allege facts that are clearly distinguishable from the facts considered by the Second Circuit in Madden.

“Yet those differences did not prevent the Colorado attorney general from citing Madden for the broad-based proposition that a non-bank that receives the assignment of a loan from a bank can never rely on federal preemption of state usury laws ‘because banks cannot validly assign such rights to non-banks.’”

Should the Federal court accept the reasoning of Madden, Pepper Hamilton’s analysis declares, such a ruling “could have severe adverse consequences for the marketplace and the online lending industry and for the banking industry generally….”

The Voice of Main Street – Small Businesses Share Their Experience With Non-bank Finance

October 18, 2017

If she hadn’t scored the $250,000 loan through Breakout Capital in 2015, Jackie Luo says, the commercial-software firm she heads in Baltimore could not have made the “strategic hires” and purchased the new server to support additional customers and maintain the company’s 30% growth rate.

“Without that infusion of capital” from the McLean (Va.)-based lender, says Luo, chief executive at E-ISG Asset Intelligence, the software solutions provider would have been hard-pressed to deploy the “bandwidth and capacity” necessary to meet burgeoning demand.

And demand there is. Luo says billing for her company’s services helping more than 100 businesses and government agencies improve operational efficiency by keeping tabs on multiple assets — human, financial and equipment — topped $1.5 million last year, up from $1 million in 2015. This year, moreover, E-ISG is on track to collect nearly $2 million.

Meantime, she says, the $250,000, 10-year note at 6% interest she obtained with the help of Breakout was both a good deal and convenient: she reports securing the financing in three weeks, compared with the six months that a commercial bank would likely have taken. In addition, she’s been able to forge a better relationship with Breakout than with a faceless financial institution.

“We are a small business,” she says, “and we’d be just one in a million at a big bank like Wells Fargo. They wouldn’t give us much attention.” With Breakout, Luo adds: “I have the freedom to make decisions about infrastructure investments without worrying about the short-term. And I don’t have to deal with people second-guessing me.”

Had she not gotten the financing, moreover, “I would not be able to pay myself,” she says. “I’d have to use my salary as working capital.”

Luo is not alone. Her company’s story of finding much-needed capital from a nonbank financial company is increasingly common. It has always been challenging for small businesses to obtain credit from a big bank — roughly a financial institution larger than $10 billion in assets. But the small and community banks that have been the lifeblood for small businesses have also been winding down their small-business lending as well, according to a March, 2016, working paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

“As recently as 1997, small banks, with less than $10 billion in assets, accounted for 77% of the small business lending market share issued by commercial banks,” co-authors Julapa Jagtiani and Catharine Lemieux write in “Small Business Lending: Challenges and Opportunities for Community Banks.” However, the market share dropped to 43% in 2015 for small business loans with origination amounts less than $1 million held by depository institutions.

“The decline is even more severe for small business loans of less than $100,000,” they add, “where the market share for small banks under $10 billion declined from 82% in 1997 to only 29% in 2015.”

The Philadelphia Fed study notes that alternative nonbank lenders are filling a widening gap. “By using technology and unconventional underwriting techniques, many alternative lenders are competing for borrowers with offers of faster processing times, automatic applications, minimal demands for financial documents, and funding as soon as the same day.” And the Fed study finds that it’s likely that nonbank lenders, which are growing rapidly, are having a positive effect by “increasing the availability of credit, particularly to newer businesses that do not have the credit history required by traditional lenders.”

The Philadelphia Fed study notes that alternative nonbank lenders are filling a widening gap. “By using technology and unconventional underwriting techniques, many alternative lenders are competing for borrowers with offers of faster processing times, automatic applications, minimal demands for financial documents, and funding as soon as the same day.” And the Fed study finds that it’s likely that nonbank lenders, which are growing rapidly, are having a positive effect by “increasing the availability of credit, particularly to newer businesses that do not have the credit history required by traditional lenders.”

Meantime, the Small Business Administration reports that small businesses remain essential to the health of the U.S. economy. Businesses with fewer than 500 employees account for 55% of overall employment in the U.S., according to the agency, and are responsible for creating two out of every three net new jobs. Which means that alternative funding sources — which do not, it is worth noting, depend on depositors’ money, as banks do — are playing an increasingly important and largely unrecognized role in the country’s economic fortunes, notes Cornelius Hurley, a law professor at Boston University and executive director of the Online Lending Policy Institute. “They’re still a small percentage of the overall lending picture,” he says of nonbank financial companies, “but they’re an emerging force and a lot of small businesspeople certainly depend on them. If they disappeared tomorrow,” he adds, “a lot of businesses would be wiped out too.”

To find out what is happening in the real world, deBanked interviewed small business owners around the country: among others, a Houston sports medicine provider, a Connecticut restaurateur, a Midwestern truck hauler, and a Maryland hardware-store owner. Some recounted being shunned by banks because of poor credit while others registered unhappiness with traditional financial institutions as inconvenient and impersonal. While some who turned to alternative lenders admitted they would have preferred not to be paying dearly for borrowing or for cash advances, most said the tradeoff was worth it.

The existence of alternative lenders has made it possible for these businesspeople to meet payrolls, pay contractors and suppliers even when business was slow or billings stalled. Customers with alternative funders – in addition to Breakout’s customers, deBanked spoke to clients of Pearl Capital Business Funding and Merchants Advance Network– also reported that they were able to purchase or replace equipment and maintain inventory, hire additional employees and accept new customers, pay for upkeep and upgrades of their business’s physical plant, and make other expenditures necessary to keep operations up-and-running.

Jason, for example, who heads a family business in Louisiana manufacturing and selling pesticides (and who asked to be identified only by his first name), reports that his suppliers began demanding that he pay in advance for chemical feedstock after he took a “financial hit following a nasty divorce.”

The roughly $1 million (annual sales) business — which was started by his parents back in 1960 — furnishes chemicals mainly to cotton farmers and homeowners in Louisiana and Texas, most of whom purchase the company’s products through feed and hardware stores. Jason says he spends a substantial amount of time on the road handling sales and distribution.

His suppliers not only require him to pay for the chemicals upfront but, following his divorce, they now insist upon larger purchases as well. Following the departure of a previous lender, he says, Breakout stepped in with an $80,000, 12-month loan in March, 2016, which he was able to repay within six months. This was followed by a $60,000 borrowing in March, 2017, which he again paid down early – in 90 days, Jason says – and the account manager at Breakout “went to bat for me and gave me an additional discount for early payment.”

His suppliers not only require him to pay for the chemicals upfront but, following his divorce, they now insist upon larger purchases as well. Following the departure of a previous lender, he says, Breakout stepped in with an $80,000, 12-month loan in March, 2016, which he was able to repay within six months. This was followed by a $60,000 borrowing in March, 2017, which he again paid down early – in 90 days, Jason says – and the account manager at Breakout “went to bat for me and gave me an additional discount for early payment.”

Had Breakout not provided external funding, Jason says, he would have been “wiped out.” He adds with feeling: “It would have meant the end of me.” And sinking the fortunes of the company would also have spelled job losses for five employees, including both his son, who works part-time, and his sister, the business’s co-manager. “Now I’m out of the hole,” he says.

In Houston, Anna, co-owner of a physical therapy and sports medicine concern, was interviewed in August just before Hurricane Harvey loomed on the horizon. “We’d been around for four years and growing rapidly,” she says, asking to be identified only by her first name, and “we couldn’t keep up with the growth.”

Anna recalls that a few years ago (she is vague about the exact dates) the company needed $50,000 to $60,000 to add equipment and staff to meet the growing demand. Because of some “ups and downs” in her business and credit history, however, a bank loan was out of the question. “My credit wasn’t the best,” Anna says, “and we had not been in business the five-to-seven years that most banks want.” She began casting about for financing and quickly saw that factoring would not be a suitable choice for a business like hers, which depends heavily on third-party payments from health insurance providers. “Companies using factoring are taking money based on credit card payments,” she says, “and we’re not a restaurant or a bar. So we can’t pay a percentage of every transaction.” Typically, she notes, getting paid by an insurance company involves a “90-day turnaround.”

Anna went online, did some research, and talked to three or four nonbank lenders searching for the “right kind of company.” That led her to Breakout. “What I really liked about them is that they did a lot of due diligence on our field,” she says. “They did their homework, asking us: ‘What are your collections and payroll? How much outstanding debt do you have?’ They also asked to see our actual bank statements.”

Anna went online, did some research, and talked to three or four nonbank lenders searching for the “right kind of company.” That led her to Breakout. “What I really liked about them is that they did a lot of due diligence on our field,” she says. “They did their homework, asking us: ‘What are your collections and payroll? How much outstanding debt do you have?’ They also asked to see our actual bank statements.”

Despite the high level of due diligence that Breakout performed, Anna says, it only took “maybe three or four days” for the loan to be approved and for the money to land in her bank account. Before long, she was off to the races. With the added capital, she hired three more employees – bringing the employee headcount to 18 — purchased more gym equipment, made payroll, and paid off miscellaneous expenses.

The added capacity and fortified staff, meanwhile, enabled the company to “almost triple its volume,” the entrepreneur says. And not only did the financing “put me in a good financial place,” Anna adds, but after repayment, Breakout made it possible for her to effect a merger with a competitor by approving a second loan for about $30,000. “The best thing about Breakout,” she says, “has been the communication. One time I did need to make a payment two or three days late. But I just called (the account manager). I was very surprised because these kinds of companies are seen as a last resort. But it was like they were investing in us.”

John Speelman, who owns Poolesville Hardware in Poolesville, Md., can boast a raft of five-star Yelp reviews online. “Extremely helpful and friendly service, surprisingly good selection (and) the complete opposite of a big box hardware chain,” raves one customer. “It is so rare to find a well-stocked store that has helpful personnel—makes this store a real gem!” says another fan.

For his part, Speelman attributes much of his hardware store’s popularity to the financing arrangement that he’s been able to work out over the past eight years with Merchants Advance Network, a Fort Lauderdale (Fla.)-based alternative funder. “It takes money to make money,” is one of his pet aphorisms.

Located roughly 35 miles west of the White House, the hardware store boasts a clientele who tend to arrive in BMW’s rather than the pickup trucks that predominated a decade or so ago in this exurban community of some 5,000 denizens. Whatever their class background, though, they’re looking for items that are not a good match for an online purchase. “People don’t buy a toilet plunger, a can of paint or picture-hanging stuff online,” Speelman says. “Because they want to do that today,” he says, “they won’t order with Amazon.”

“One industry that has not been impacted” by online merchandisers, he adds, “is the garden center. They’ll buy a garden hose, weed killer and seeding,” he explains of his regular customers. “And light bulbs” while they’re there, he adds. “We’re like the 7-Eleven — a convenience store.”

To guarantee that convenience, Speelman pays cash-in-advance for most of his inventory, and banks have not been helpful. He contrasts the relationship he has with Michael Scalise, the chief executive at Merchants Advance, with loan officers at commercial banks. “It’s hard to get a loan for anything in retail,” he says. Never mind that he maintains “a high credit rating and I never bounce a check,” he went on. “There are no more local banks. At M&T Bank, all the managers I knew are gone and there’s always a new teller. The banking industry is a revolving door.” So he opts for capital from Merchants Advance “when I need 30-40-50 grand in a day, I use Mike’s money” even though the cost can be as steep as 25%, he says. If he doesn’t have something in stock – specialty items like ammo boxes, a Sugarplum tent, as many as 32 packs of size D batteries, metric measuring tapes – he can put in a special order with suppliers. But he prides himself on the full panoply of wares on his shelves. “You can’t sell from an empty cart,” is another of his favorite sayings.

Lori Hitchcock, who also draws capital from Merchants Advance, is manifestly displeased with the banking industry. She’s an owner with her husband of Hitchcock Trucking, the couple’s 60-year-old family business, which is located on a ten-acre tract in Webberville, Mich., situated between Detroit and Lansing, the state capital.

Of her experience with banks, Hitchcock says: “At the time we went with (Merchants Advance), banks weren’t lending. And they’re still not lending. We’re considered high-maintenance and high-risk. Banks don’t want a bunch of trucks” should they foreclose on a loan, she observes. “If you’re a farmer, they can take all your land. Great! In this crazy world you live in, it’s hard to get the banks interested.”

The Hitchcock family’s fleet of ten Peterbilt semis hitch up to more than 20 trailers and truck bodies – flatbeds, dump trucks, vans, and refrigerated trucks or “reefers” – and haul grain, sweet corn, onions, celery, fertilizer, and soft drinks across the Midwest. Most recently, she says, the family business took out $80,000 from Merchants Advance to expand its fleet and buy another reefer trailer and a backhoe. “Out here in the country, you always need a backhoe,” she says.

The Hitchcock family’s fleet of ten Peterbilt semis hitch up to more than 20 trailers and truck bodies – flatbeds, dump trucks, vans, and refrigerated trucks or “reefers” – and haul grain, sweet corn, onions, celery, fertilizer, and soft drinks across the Midwest. Most recently, she says, the family business took out $80,000 from Merchants Advance to expand its fleet and buy another reefer trailer and a backhoe. “Out here in the country, you always need a backhoe,” she says.

To satisfy her lender, the company makes daily ACH payments. “I’m not going to lie and say that things aren’t tight,” she says. “It is a burden. You just have to have constant cash-flow – which we do have. And it’s important to have good relationships…I can usually tell three weeks in advance if (making payments) is going to be challenging. So it all comes down to being loyal to people.”

Whatever the struggle to keep up with debt payments, it beats using her own money. “My husband and I are raising a family,” Hitchcock says, “and it’s nice having the cash so you’re not putting your personal earnings into the company.”

In Manchester, Conn., a stone’s throw east of Hartford, Corey Wry says that he wouldn’t be able to operate his two, highly rated restaurants just off Interstate 84 – Corey’s Catsup & Mustard and Pastrami on Wry – if he didn’t have funding from Pearl Capital, a New York (N.Y.)-based alternative funding company. A graduate of Johnson & Wales University in Providence, a restaurant-and hotel school, Wry describes himself as “a culinary guy” whose first love is serving food that’s both innovatively prepared and delicious. He candidly admits that his credit hit “rock bottom” after a confluence of untoward events.

Last year, a third restaurant in town, Chops & Catch, that he and some partners had “bootstrapped” had to shut down after six years of operation. Despite generally favorable reviews for such creative fare as the “lobsterburger,” the surf-and-turf themed restaurant was a money-loser. He was also struggling to pay off credit cards. And he’d been late more than once on car payments.

At the same time, Wry was in the process of moving Pastrami & Wry — a deli whose moniker is wordplay on his last name – to a new location. Both the general contractor and electrician were “over-budget” on that project, he says. Meanwhile, Catsup and Mustard, a hamburger spot, needed to be spruced up. Says he: “It was getting busier and the original seats were worn. I had a hole in a booth big enough to swallow someone.”

He approached a few banks for a loan and “it did not seem like it was going to happen,” he says. “Then I got a cold call from one of these financiers. Some of them had super-high rates. When you have bad credit but need to make capital improvements you do what you have to do.”

He’s accessed more than $100,000 from several alternative funding sources, including Pearl – from which he reports getting merchant cash advances for $30,000. But hard as it is to meet the obligations, which typically require a daily ACH payment, the financing has made renovating the burger place possible. Moreover, he’d still be on the hook with plumbers and other contractors – all of whom are local tradesmen and would likely be paying him personal visits until they were repaid — for the relocation of Pastrami & Wry.

“Business is good,” says Wry, who at 40 is single, often works 15-hour days, and says that he doesn’t have time for a girlfriend, much less a wife and family. “I’ve still got $3,200 on the books with the electrician,” he adds, “which means that I won’t be able to purchase a deli slicer. I have to plan these things out…”

James McGehee, a partner at the boutique accounting and tax-preparation firm McGehee, Davis & Associates, which is located in the Denver suburb of White Ridge, reports that the firm took a merchant cash advance from Pearl Capital, among other financiers, to bridge the gap between tax season and the rest of the year when billings invariably diminish. “Our overhead is pretty high,” he explains. “We’ve added two employees. We’ve been expanding on what we were doing, adding tax and accounting clients.”

A very conservative, sober-sounding man, McGehee explained that his credit was nonetheless “trashed” after he suffered from health problems five years ago. “Major stuff,” he says, “it was open-heart surgery.” The medical ordeal meant that he could not work for a time and had trouble paying his bills. “Some family members helped me through the mortgage and utilities payments and I ended up in arrears and in credit card debt,” he says.

All of which made an alternative source of financing his firm’s only option. “I’m not sure how we heard about Pearl,” he says. “I think they just happened to call. We took out [$11,000]. It was not a huge amount. We also borrowed $9,000 from another entity. We paid it all back during tax season. The terms were pretty steep,” McGehee adds.

“But when you need the money for cash-flow,” he explains, “you just absorb it. You grin and bear it. When you need the money, you need the money.”

Tech Banks: Will Fintech Dethrone Traditional Banking?

August 20, 2017On Halloween, 2014, a largely unknown, Boston-based financial institution, First Trade Union Bank, embraced high-technology, went paperless, and officially adopted a new name: Radius Bank.

In reinventing itself, Radius did more than dump its dowdy moniker. It shuttered five of its six branches, re-staffed its operations with a tech-savvy team, instituted “anytime/anywhere” banking services, and offered customers free access to cash via a nationwide ATM network. And it teamed up with a fistful of financial technology companies to offer an impressive array of online lending and investment products.

In reinventing itself, Radius did more than dump its dowdy moniker. It shuttered five of its six branches, re-staffed its operations with a tech-savvy team, instituted “anytime/anywhere” banking services, and offered customers free access to cash via a nationwide ATM network. And it teamed up with a fistful of financial technology companies to offer an impressive array of online lending and investment products.

Today, the bank’s management boasts that, using their personal mobile phones, some 2,700 people per week are opening up checking accounts, funneling $3 million in consumer deposits into the bank’s virtual vault. That’s a stark contrast from a decade ago when the financial institution was being rocked by the financial crisis and “we couldn’t get anybody to walk into our branches,” says Radius’s chief executive, Mike Butler.

“We tried to leave that old bank behind,” he says. “We’re a virtual retail bank now, an efficiently run organization that offers high levels of customer service and Amazon-like solutions.”

Radius Bank is not alone. At a moment when there is much discussion — and hand-wringing — over the future of seemingly outmoded, highly regulated community banks, a coterie of small but nimble banks is exploiting technology and punching above its weight. Almost overnight, this cohort is combining the skill and hard-won experience of veteran bankers with the lightning-fast, extraordinary power afforded by the Internet and technological advances. As a result, these small and modest-sized institutions are redefining how banking is done.

In addition to Radius Bank, independent banks winning recognition for their bold, innovative – and profitable — exploitation of technology, include: Live Oak Bank in Wilmington, N.C., which adroitly parlays technology to become the No. 2 lender to business and agricultural borrowers backed by the U.S. Small Business Administration; Darien Rowayton Bank in Darien, Conn., which is making a name for itself with coast-to-coast, online refinancing of student loans; and Cross River Bank in Fort Lee, N.J., which does back-end work for a passel of fintech marketplace lenders.

Interestingly, there’s not much overlap. Each of the banks goes its own way. But what all the banks have in common is that each has struck out on its own, each hitting upon a technological formula for success, each experiencing superior growth.

“These are companies that understand the value of a bank charter,” says Charles Wendel, president of Financial Institutions Consulting in Miami. “They have to work under the watchful eyes of state and federal regulators. But their cost of funds is low and they can offer more attractive rates. Because they’re less likely (than nonbank fintechs) to disappear, run out of money, or get sold,” the bank expert adds, “they also have the image of stability with customers.”

These modest-sized banks are emerging as not only pacesetters for the banking industry. Along with making common cause with the fintechs — which had promised to disrupt the banking industry – they’re even beating the fintechs at their own game.

“Classically, community banks have looked to technology partners to provide technological innovation,” says Cary Whaley, first vice-president for payment and technology policy at the Independent Community Bankers of America, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing a broad swath of the country’s 5,800 Main Street banks. “They still do. You’re seeing more partnerships. But now you also see community banks building innovative products and services outside of that relationship. You see forward-thinking banks developing their own technology to support big ideas like marketplace lending, distributed ledger technology, and emerging payments technology.”

With its extraordinary skill at exploiting technology, Live Oak Bank – which trades on the Nasdaq and is the only public company encountered in the cohort — has become a Wall Street darling. “While several banks have adopted an online-only model, and nearly all banks are shifting more and more delivery through online channels, Live Oak was built from the ground up as a technology-based bank,” Aaron Deer, a San Francisco-based research analyst at Sandler O’Neill Partners, wrote in a recent investment note.

Driving the success of Live Oak, which operates out of a single branch in the North Carolina seacoast town and has only been in business for a decade, is the explosive growth in its SBA lending, the bank’s “core strategy,” Deer notes. Last year, Live Oak lent out $709.5 million in SBA loans in increments of up to $5 million, the federal agency reports, making it the country’s No. 2 SBA lender. It trailed only megabank Wells Fargo Bank, the third largest bank in the U.S. with $1.5 trillion in assets, which made $838.93 million in SBA-backed loans last year.

As its SBA lending has taken off, Live Oak, which qualifies as a “preferred lender” with the federal agency, boasts assets that have nearly tripled to $1.4 billion in 2016, up from $567 million two years earlier. Those are flabbergastingly fantastic growth numbers. But just as incongruously — by nipping at the heels of Wells Fargo — Live Oak has been challenging a bank more than a thousand times its asset size for dominance in SBA lending.

And, interestingly, the bank is able to book those outsized amounts of SBA loans while lending to only 15 industries out of 1,100 approved by the government agency, slightly more than 1% of the universe. That’s up from 13 industries in 2015, and Live Oak is adding two to four additional industries yearly for its SBA loan portfolio, Deer reports. Included among the industries to which the bank made an average SBA loan of $1.29 million last year: Agriculture and poultry, family entertainment, funeral services, medical and dental, self-storage, veterinary, and wine and craft-beverage.

The bank has a team of financing specialists dedicated to each of the designated industries. Among Live Oak’s current SBA borrowers are Martin Self Storage in Summerville, S.C.; Utah Turkey Farms in Circleville, Utah; Pinballz Arcade, Austin, Tex.; and Council Brewery Company in San Diego. Steve Smits, chief credit officer at the bank, told NerdWallet: “When you specialize in something, you become efficient. Because we do it every day and we have professionals and specialists, we tend to be more responsive and quicker.”

The heady combination of technological sophistication and banking expertise has allowed the lender to slash its loan-origination time to 45 days, about half the three-month industry average for SBA loans. To speed up loan sourcing and generation, the bank developed its own in-house technology, which led to the formation of the Wilmington-based technology company nCino, which was spun off to shareholders in 2014.

Live Oak did not return calls to discuss its lending strategies, but in SEC filings bank management declared: “The technology-based platform that is pivotal to our success is dependent on the use of the nCino bank operating system” which relies on Force.com’s cloud-computing infrastructure platform, a product of Salesforce.com.

Natalia Moose, a public relations manager at nCino told deBanked in an e-mail interview: “We work with Live Oak Bank, in addition to more than 150 other financial institutions in multiple countries with assets ranging from $200 million to $2 trillion, including nine of the top 30 U.S. banks. nCino was started by bankers at Live Oak Bank who found the logistics of shuffling paperwork among loan stakeholders to be unwieldy, inefficient and time-consuming.

“nCino’s bank operating system,” Moose adds, “leverages the power and security of the Salesforce platform to deliver an end-to-end banking solution. The bank operating system empowers bank employees and leaders with true insight into the bank, combining CRM (customer relationship management), deposit account opening, loan origination, workflow, enterprise content management, digital engagement portal, and instant, real-time reporting on a single secure, cloud-based platform.”

Live Oak, meanwhile, is not resting on its technological laurels. According to Deer’s report, the bank’s parent company, Live Oak Bancshares, has formed a subsidiary to inject venture capital into fintech companies. It’s already taken a small equity stake in Payrails and Finxact, “the latter of which is developing a completely new core processor to compete against the old legacy systems used by most banks,” the Sandler O’Neill analyst writes. “Quite simply,” he asserts elsewhere in his report, “the company is far beyond any other bank we cover in its technical capabilities and the growth outlook remains outstanding.”

Five hundred and thirty-three miles due north along the Atlantic coast in southeastern Connecticut, Darien Rowayton Bank is also experiencing tremendous success as a lender using a home-grown technology platform. State-chartered by the Connecticut Department of Banking and regulated as well by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the $600 million-asset bank is winning attention in banking circles for its online student-loan refinancing.

Five hundred and thirty-three miles due north along the Atlantic coast in southeastern Connecticut, Darien Rowayton Bank is also experiencing tremendous success as a lender using a home-grown technology platform. State-chartered by the Connecticut Department of Banking and regulated as well by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the $600 million-asset bank is winning attention in banking circles for its online student-loan refinancing.

A few years ago, DRB, as it is known, was looking to go beyond mortgage and commercial lending — “the bread and butter for most community banks,” bank president Robert Kettenmann explained to deBanked in a telephone interview – and was somewhat at a loss. The bank considered but then rejected the credit card business. Finally, DRB struck paydirt refinancing student loans. “Our chairman really seized on the opportunity,” Kettenmann says, adding: “It’s a $35 billion market.”

Thanks to the National Bank Act, it’s able to operate in all 50 states. As a regulated commercial bank with a strong deposit base, DRB can also offer low rates well below any state’s usury prohibitions.

What is most striking about DRB’s program is its nationwide targeting of upwardly mobile, affluent young professionals. According to a PowerPoint presentation obtained by deBanked, all of the bank’s super-prime borrowers, who are mainly in the 28-34 age bracket, have a college degree and a whopping 93% have graduate degrees. Average income is $194,000.

Forty-eight percent of those refinancing student loans with DRB are doctors or dentists and another 22 percent are pharmacists, nurses or medical employees; only about 20% are paying off their law degrees or MBAs. The heavy concentration of refinancing in the medical field reduces economic risk in an economic downturn. Forty-three percent of the borrowers are home-owners, the rest are renters – and prime candidates for an online, DRB-financed mortgage.

Forty-eight percent of those refinancing student loans with DRB are doctors or dentists and another 22 percent are pharmacists, nurses or medical employees; only about 20% are paying off their law degrees or MBAs. The heavy concentration of refinancing in the medical field reduces economic risk in an economic downturn. Forty-three percent of the borrowers are home-owners, the rest are renters – and prime candidates for an online, DRB-financed mortgage.

(Once known as “yuppies” today this cohort is “known by the acronym ‘HENRY,’” remarks Cornelius Hurley, a Boston University banking professor and executive director of the Online Lending Institute, explaining the initials stand for “High Earners Not Rich Yet.”)

The Connecticut bank partnered with a third-party on-line vendor, Campus Door, when it commenced making student loans in 2013. In the fall of 2016, however, DRB built out its own, proprietary loan-origination system, Kettenmann reports, emphasizing that CampusDoor had been an excellent partner but that the bank wanted to exercise end-to-end control over the process. DRB employs a seven-pronged, “omni-channel” marketing approach that includes interactive marketing, affinity partnerships, digital/online advertising, direct mail, mass-media advertising, and public relations/brand awareness campaigns.

DRB’s online enrollment provides “pre-approved rates” in less than two minutes with final approval on rates in 24-48 hours. Refinancers can complete the online application at their own speed. Through May, 2017, DRB had made $2.48 billion in refinancing to 20,000 student-loan borrowers, with only ten defaults, five of which were attributed to deaths or “terminal illness.”

On Yelp! the bank has received a batch of reviews ranging from very favorable, five-star (“I had a truly wonderful experience”) to one-star (“awful” and “truly a nightmare”). Many fault the application process as laborious, describing it as “time-consuming.” But for those who have succeeded, like the reviewer who counseled “patience,” the result can be “the lowest rate with DRB…my loan payments went down $100 a month.”

Just about an hour’s drive south and taking its name from its proximity to New York city just over the George Washington Bridge is New Jersey-based, state-chartered Cross River Bank, which has a reputation as a partner-in-arms to fintech companies. “We’re both users and producers of technology,” declares Gilles Gade, the bank’s chief executive.

Just about an hour’s drive south and taking its name from its proximity to New York city just over the George Washington Bridge is New Jersey-based, state-chartered Cross River Bank, which has a reputation as a partner-in-arms to fintech companies. “We’re both users and producers of technology,” declares Gilles Gade, the bank’s chief executive.

The bank provides “back-end” and infrastructure support to 17 marketplace lenders that offer a suite of lending products including personal loans, mortgages and home-equity loans. Following loan origination by a fintech company – Marlette Funding, Affirm, Upstart, loanDepot, SoFi, and Quicken Loan, among other partners — Cross River does the actual underwriting. Last year, Gade reports, the bank underwrote 1.9 million loans valued at $4-4.5 billion, about 10% of which Cross River kept on its books. The bulk of the loans are sold “back to the marketplace lenders” or to a third party. “We’ve created a high-velocity automated system,” he says.

Gade is manifestly unapologetic about the bank’s role in assisting fintechs in their competition with the banking establishment. “We’re a banking infrastructure services provider for those who want to disrupt the banking system,” he says. “Consumers expect a lot better than they’ve been getting from traditional banking services.”

Back in Boston, Radius Bank’s chief executive reports that forging partnerships with fintechs to provide the full panoply of online banking services was no easy proposition. In its mating ritual, Radius not only had to determine that a fintech company’s offerings were sound and that it had the right characteristics – most especially “a long-term, sustainable business model” – but that its corporate culture meshed comfortably with Radius’s.

Back in Boston, Radius Bank’s chief executive reports that forging partnerships with fintechs to provide the full panoply of online banking services was no easy proposition. In its mating ritual, Radius not only had to determine that a fintech company’s offerings were sound and that it had the right characteristics – most especially “a long-term, sustainable business model” – but that its corporate culture meshed comfortably with Radius’s.

After meeting with as many as 500 fintechs and after a fair amount of trial and error, Radius formed partnerships with LevelUp, which enables customers to make mobile payments; with online lender Prosper, for refinancing consumer debt and “credit rehabilitation”; with SmarterBucks, for refinancing student loans; and with online investment firm Aspiration Partners – which allows investors to name their own fees and markets itself to a predominately middle-class audience as the firm “with a conscience.”

Radius employs advertising on social media websites and employs “psychographics” to appeal to “anyone who is zealous about using technology, not necessarily millennials,” Butler says. The data show that 65% of adults in the U.S. would prefer to use a traditional bank and have face-to-face interactions with a teller, he notes, leaving the remaining 35% as Radius’s target audience.

Christopher Tremont, executive vice-president for virtual banking, told deBanked that a typical Radius customer is 42 years old, lives in Boston, New York, Chicago “or one of the bigger cities in the West,” is a “technophile,” earns $75,000 a year, and has $100,000 in personal assets.

Radius’s performance since it went paperless has been stellar. The bank has seen a rapid rise in deposits, spurting to $782 million through the first quarter of 2017, up from $565 million at year-end 2014. With little fee income but ample deposits and low-cost funds, Radius realizes the bulk of its revenues – and profits — on the interest-rate spread generated from its loan portfolio.

The bank booked $43.5 million in SBA loans last year, ranking it in the top 50 banks on the SBA’s league tables, while carrying another $105 million in its commercial leasing business at the end of the first quarter this year. Loan generation is driving asset growth, which are currently at $973 billion, up more a third from $726 million in 2014, and Butler expects the bank’s assets to top $1 billion sometime this year.

“Community banks love that part of the business—lending money,” Butler says.

The ‘Loan’ Star State – Texas is an alternative finance nexus

June 15, 2017

We’re at Able Lending in Austin, Texas, a financial technology company occupying three floors deep in the heart of the Seaholm power plant overlooking Lady Bird Lake. The fortress-like building anchors an inner-city complex of offices and residences, chic restaurants, boutique shops, and a Trader Joe’s.

Once the main source of electricity for Texas’s capital city, the natural gas-fired boilers have given way to a warren of glassed-in offices and meeting rooms connected by angular metallic stairways and a carpeted mezzanine.

It is here, in a tiny conference room, that Will Davis, a slim man of 35 and an alumnus of Harvard Business School, is drawing a bell curve on a whiteboard. Dressed for the balmy Texas weather in tan Bermuda shorts, a black tee-shirt and Nike running shoes, the company’s chief executive and co-founder is explaining how Able’s friends-and-family lending formula “widens” the risk curve.

“We all compete here in this box on price,” Davis says, drawing a square at the topmost point of the bell curve, indicating where the near-prime borrowers abide and where lenders are crowded in pursuit. But when loans from friends and family form 10%-15% of the total loan, he says, drawing squiggly lines just to the left of the box, a cohort with less-than-stellar credits now becomes credit-worthy.

Because of the “peer pressure” and “behavioral change” exerted by the involvement of family and friends, the formula produces a “positive-selection effect on the loan portfolio” Davis says, declaring: “We can serve more of the market.”

It all sounds very business-schoolish. But here’s the bottom line: Able’s lending model sharply reduces both risk and borrowing costs, allowing it to go head-to-head with national rivals like Funding Circle, Bond Street, OnDeck and StreetShares. Thanks in large part to its reduced risk, asserts Able’s director of development, 30-year-old Matt Irving, the Austin fintech can lend twice as much money as its competitors at half the interest rate.

Since opening its doors and firing up its computers in the fourth quarter of 2014, Able’s average loan size has climbed to $231,200 from $100,000. Of that, an average of 3.2 “backers” have accounted for $40,691, or 17.6% of the average total loan amount. The average “blended” annual percentage rate is 16.41%.

Meanwhile, Able, which has made some $48 million in loans to entrepreneurs through the end of April, 2017, reports CEO Davis, is itself on sound financial footing. According to the data-services firm Crunchbase, Able has raised $12.5 million in three rounds of venture capital financing from 21 investors. Principal equity financiers are Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, Peterson Ventures, RPM Ventures, and Blumberg Capital. On Sept. 27, 2016, moreover, Able added another $100 million to its arsenal in debt financing from Community Investment Management, a San Francisco investment firm. Borrowers include owners of food trucks and apparel shops; professionals including doctors, dentists, veterinarians, and accountants; “creatives” like public relations and advertising firms; and construction companies. Since its inception, Davis says, just one borrower has defaulted, resulting in an $85,000 charge-off.

So far in 2017, the company has lent out nearly $15 million in the first quarter, but it’s on track to make $80 million this year. “We’re ramping up,” Davis declares.

Welcome to fintech in the Lone Star State. While everything may be bigger in Texas, as the saying goes, that’s not quite true of financial technology. The geographic contours of fintech operations are roughly 60% in California (especially Silicon Valley/San Francisco), 30% New York, and 10% scattered about the rest of the country, says 40-year-old Mihir Korke, the San Francisco-based chief marketing officer at Able.

Nonetheless, Texas offers fertile ground for the burgeoning fintech industry. The vaunted Texas business climate promises a relaxed regulatory regime, the absence of either a personal or corporate income tax, and a lower cost of living. All of which were cited by Able Lending, as well as an additional pair of fintech companies that specialize in factoring and merchant cash advances: Jet Capital, located in North Richland Hills in the Dallas-Fort Worth “metroplex”; and Ironwood Finance in Corpus Christi, a port city on the Gulf of Mexico.

“What’s interesting about fintech companies is that they can choose to locate where they want to do business,” says Erin Fonte, an attorney at Dykema Cox Smith in Austin whose legal practice includes mobile payments, mobile wallets and financial technology. “They don’t necessarily get a regulatory advantage because much of what they do is based on their customers’ location,” says Fonte, who is currently serving as a member of the Federal Reserve’s Faster Payments Taskforce. “That said,” she adds, “some companies have chosen to locate in Texas because of the labor and talent pool, because it’s a good source of venture capital, and it’s more affordable.”

Jet Capital’s 42-year-old chief executive, Kenneth Wardle, confirms many of Fonte’s observations. “So far, Texas has been friendly to MCA companies,” he says, using the initials for “merchant cash advance.” Especially favorable to his industry is the fact that “Texas regulators do not define an MCA as a loan,” he adds.

Prior to co-founding Jet Capital with chief operating officer Allan Thompson, 49, Wardle served as a portfolio manager at Exeter Finance Corp, a $3 billion company in nearby Irving which specializes in subprime auto financing. Wardle has also held leadership positions at AmeriCredit Corp., now GM Financial, and Drive Financial, now Santander Consumer USA.

His 20-year background has included the gritty work of repossessing cars when owners fell into arrears on their auto loans. “Most of my career in auto finance was in risk management and I’ve driven a repo truck,” he says. “You take off with the car right away and then chain it down after you’ve gone a couple of blocks so you don’t lose it out on the highway.”

Backed by more than $5 million in equity financing from a family office in Puerto Rico, Jet Capital makes cash advances of $25,000-$30,000, on average, for working capital.

The sweet spot for Jet’s financings are retail establishments, trucking companies, hair-and-nail spas, and medical doctors. Doctors in particular are prime candidates for a Jet cash advance. “They have a pretty good gap between when they perform services and when they get paid by insurance companies” during which they have to cover payroll expenses and overhead, Wardle notes. Prospecting for customers is done largely through independent sales offices, direct mail, and pay-per-click services offered by Google, among additional online channels.

“Our defaults are relatively in line with expectations” and were largely confined to the first year of business, Wardle says. “We made some underwriting and verification changes last September and October,” he adds, “and we changed our minimum credit scores. Since then we’ve seen defaults migrate in the right direction.”

Since Wardle and Thompson took occupancy of an empty office outside Fort Worth in October, 2015, Jet has grown to 12 employees who today have “a variety of roles” says Thompson, citing sales, underwriting, customer service, collections, analytics, and information technology. “They wear a lot of hats and there’s a lot of cross pollination,” he says.

Since Wardle and Thompson took occupancy of an empty office outside Fort Worth in October, 2015, Jet has grown to 12 employees who today have “a variety of roles” says Thompson, citing sales, underwriting, customer service, collections, analytics, and information technology. “They wear a lot of hats and there’s a lot of cross pollination,” he says.

Looking ahead, Wardle foresees Jet expanding its product line beyond merchant cash advances to offer lines of credit and installment loans. “Our goal is to be a one-stop, nonbank financing solution,” Wardle says.

Kevin Donahue, 37, owner of Ironwood bootstrapped the South Texas company, which opened in 2013 using personal savings of $1.5 million remaining from the sale of mobile home parks in South Dakota and Texas. He also plowed earnings into Ironwood from a subsequent job as a commercial loan broker.

Donahue, who grew up in a family of fishermen on the Oregon and California coasts and is a 2006 graduate of California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo, says that he turn up in Corpus Christi somewhat by accident. While operating the mobile home park in nearby Kingsville, he got married, started a family, and put down roots.

With 20 employees, Ironwood focuses on providing merchants cash advances in the $5,000 – $50,000 range, Donahue says, “but we can go up to $1 million.” The average cash advance – usually $10,000-$15,000 – is put to use as working capital by what he dubs “Main Street” businesses: restaurants, boutiques, trucking and transportation companies, professionals, and contractors. Ironwood charges clients factoring fees that are collected via ACH.

“Many times (these businesses) don’t qualify for bank loans,” Donahue says. And even when they do qualify, he notes, “banks take forever – up to three months – while we’re using our own money and can do it in three days. We’re very low on requiring a lot of documents.”

For his part, Donahue wants to see a customer’s bank statements, a photo I.D., voided checks, and a financial report. But, he says: “Cash flow is much more important than financials.”

Clients typically find their way to Ironwood through the website, although they often arrive through referrals from brokers and real estate agents, attorneys, accountants and “anyone doing commercial lending,” he says. Donahue says he closed down a call center. “The way to get leads is more through relationships than marketing,” he says.

Trucking companies are important customers. “They work on thinner margins, the barriers to entry are lower, sometimes their customers don’t pay their bills,” Donahue says of the industry’s economics. “They have huge expenses for fuel, payroll, insurance – and they might not get paid (by their customers) for 30 days or more.”

Ironwood’s advance for a million dollars, cited earlier, was made to a trucking company in Midland, Texas, which hauled both general freight and oilfield equipment. The money was put to use both to smooth out cash flow and as growth capital. The trucking concern “used part of that for expansion, making down-payments with Volvo or Peterbilt,” Donahue recalls.

Backstopped by the titles for 18 trucks valued at roughly $1.5 million, the deal was structured as a three-year, sale-leaseback agreement with “no interest” but rather a fee, Donahue says. Payments were $32,000 monthly, he says, amounting to $152,000 above the advance.

Donahue has no trouble justifying the steep fee schedules. Not only does he release money quickly but in many instances Ironwood has stepped in to bail out businesses that could have gone belly-up. He cites a trucker in the Midwest who had a “very lucrative” business hauling Boeing jet engines worth $30 million to Seattle where they could be worked on and returned to the planes for installment. In order to fulfill the contracts – which earned the hauler $25,000 monthly — the trucking company’s owner needed to purchase pricey insurance.

The owner, however, “had horrible credit,” Donahue says, largely the result of cash flow problems after investing in a special trailer for the jet engines, compounded by a messy divorce. To secure the $10,000 for the special insurance, the trucker sold Ironwood $14,000 of their future receivables. “For his investment of $4,000 he’s making $25,000-a-month forever,” Donahue explains.

Back in Austin, Able is gearing up for another round of capital-raising to bulk up staff and, according to Korke, win licensing to do business in California. At the same time, its friends-and-family credit structure is winning kudos for reaching what researcher David O’Connell calls “the unloaned.”