Articles by Ed McKinley

The Dual Aura of Fora – How Two College Friends Built Fora Financial and Became the “Marketplace” of Marketplace Lending

February 16, 2016A recent Bloomberg article documented the hard-partying lifestyle of two young entrepreneurs who struck it rich when they sold their alternative funding business. The story of their beer-soaked early retirement in a Puerto Rico tax haven came complete with photos of the duo astride horses on the beach and perched atop a circular bed.

But two other members of the alternative-finance community have chosen a different path despite somewhat similar circumstances. Jared Feldman and Dan B. Smith, the founders of New York-based Fora Financial, are about the same age as the pair in that Bloomberg article and they, too, recently sold an equity stake in their company. Yet Smith and Feldman have no intention of cutting back on the hours they dedicate to their business or the time they devote to their families.

They retained a share of Fora Financial that they characterized as “significant” and will remain at the head of the company after selling part of it to Palladium Equity Partners LLC in October for an undisclosed sum. Palladium bought into a company that has placed more than $400 million in funding through 14,000 deals with 8,500 small businesses. It expects revenue and staff size to grow by 25 percent to 35 percent this year.

The deal marks Palladium’s first foray into alternative finance, although it has invested in the specialty-finance industry since 2007, said Justin R. Green, a principal at the firm. His company is appointing two members to the Fora Financial board.

Palladium, which describes itself as a middle-market investment firm, decided to make the deal partly because it was impressed by Smith and Feldman, according to Green. “Jared and Dan have a passion for supporting small businesses and built the company from the ground up with that mission,” he said. “We place great importance on the company’s management team.”

Negotiations got underway after Raymond James & Associates, a St. Petersburg, Fla.-based investment banking advisor, approached Palladium on behalf of Fora Financial, Green said. RJ&A made the overture based on other Palladium investments, he said.

The potential partnership looked good from the other point of view, too. “We wanted to make sure it was the right partner,” Feldman said of the process. “We wanted someone who shared the same vision and knew how to maximize growth and shareholder value over time and help us execute on our plans.”

It took about a year to work out the details of the deal Feldman said. “It was a grueling process, to say the least,” he admitted, “but we wanted to make sure we were capitalized for the future.”

It took about a year to work out the details of the deal Feldman said. “It was a grueling process, to say the least,” he admitted, “but we wanted to make sure we were capitalized for the future.”

The Palladium deal marked a milestone in the development of Fora Financial, a company with roots that date back to when Smith and Feldman met while studying business management at Indiana University.

After graduation, Feldman landed a job in alternative funding in New York at Merchant Cash & Capital (today named Bizfi), and he recruited Smith to join him there. “That was basically our first job out of college,” Feldman said.

It struck Smith as a great place to start. “It was the easiest way for me to get to New York out of college,” he said. “I saw a lot of opportunity there.”

The pair stayed with the company a year and a half before striking out on their own to start a funding company in April 2008. “We were young and ambitious,” Feldman said. “We thought it was the right time in our lives to take that chance.”

They had enough confidence in the future of alternative funding that they didn’t worry unduly about the rocky state of the economy at the time. Still, the timing proved scary.

Lehman Brothers crashed just as Smith and Feldman were opening the doors to their business, and all around them they saw competitors losing their credit facilities, Smith said. It taught them frugality and the importance of being well-capitalized instead of boot-strapped.

Their first office, a 150-square-foot space in Midtown Manhattan, could have used a few more windows, but there was no shortage of heavy metal doors crisscrossed with ominous-looking interlocking steel bars. The space seemed cramped and sparse at the same time, with hand-me-down furniture, outdated landline phones and a dearth of computers. Job seekers wondered if they were applying to a real company.

“It was Dan and I sitting in a small room, pounding the phones,” Feldman recalled. “That’s how we started the business.”

At first, Smith and Feldman paid the rent and kept the lights on with their own money. Nearly every penny they earned went right back into the business, Feldman said. The company functioned as a brokerage, placing deals with other funders. From the beginning, they concentrated on building relationships in the industry, Smith said. “Those were the hands that fed us,” he noted.

By early 2009, Smith and Feldman started raising capital from friends and family members so that they could fund deals themselves. About that time, they developed a computer platform to track the payments they received from funding companies where they placed deals.

Smith and Feldman’s first credit facility came from Entrepreneur Growth Capital. The stake enabled them to begin handling deals on their own instead of passing them along to funders. At the same time, they expanded their computing platform to handle entire deals.

From there, Smith and Feldman expanded their computing capability to help with accounting, underwriting and other functions. A combination of staff and outside developers guided the platform’s evolution. Today, three full-time in-house tech people handle programming.

Smith and Feldman emphasize that they don’t consider Fora Financial a tech company, but Green said the company’s platform helped cinch the deal. “We view Fora Financial as a technology-enabled financial services company,” he maintained.

While building the platform and expanding the business, Fora Financial secured mezzanine financing from Hamilton Investment Partners LLC, a company that bases its investments on the strength of management teams. “I am industry-agnostic,” said Douglas Hamilton, managing partner and and cofounder. “Dan and Jared are one of the best young teams I have encountered in my 35 years of doing private investing.”

Meanwhile, Fora Financial moved six times to larger accommodations. The company’s 116 employees now occupy 26,000 square feet in Midtown, with half of the staff working in direct sales and the other half devoted to back office, underwriting, finance, IT, customer service, collections and legal duties.

Meanwhile, Fora Financial moved six times to larger accommodations. The company’s 116 employees now occupy 26,000 square feet in Midtown, with half of the staff working in direct sales and the other half devoted to back office, underwriting, finance, IT, customer service, collections and legal duties.

Seventy percent of the company’s business flows from its inside sales staff and the rest comes from ISOs, brokers and strategic partners, Feldman said. “Most of the industry is the opposite,” he noted.

Finding salespeople presents a challenge in New York, where they’re in great demand. “We’ve invested a lot of money in finding the right salespeople,” Feldman said. “We also have to make sure that we’re right for them.” The sales staff includes recent graduates and experienced people from other sectors of financial-services or other businesses, Feldman noted.

“We don’t hire from within the industry,” Smith added. “From Day One, we’ve been training our staff our way and not bringing in tainted brokers.” That way, the company can make sure salespeople hew to the company’s ethical approach to business, he maintained. It’s part of creating a company culture, he said.

The Fora Financial culture also includes strict compliance with state and federal regulation because until recently Smith and Feldman owned the entire company, Feldman said. “Regulatory compliance is a core value with us and has been for some time,” he noted, adding that it’s also resulted in conservatism and due diligence.

Those traits have not gone unnoticed, according to Robert Cook, a partner at Hudson Cook, LLC, a Hanover, Md.-based financial-services law firm that has worked extensively with the company. “Fora was one of the first clients in this small-business funding area that took compliance to heart,” Cook said. “As time has gone on, we’re seeing more and more companies make compliance part of their culture, but Fora was one of the early adapters in this area.”

Those traits have not gone unnoticed, according to Robert Cook, a partner at Hudson Cook, LLC, a Hanover, Md.-based financial-services law firm that has worked extensively with the company. “Fora was one of the first clients in this small-business funding area that took compliance to heart,” Cook said. “As time has gone on, we’re seeing more and more companies make compliance part of their culture, but Fora was one of the early adapters in this area.”

Top management at alternative finance companies often talk about compliance, and the discussion too often ends there and doesn’t filter down through the ranks, Cook said. But that’s not the case at Fora Financial, he maintained. “It’s throughout the organization,” he said of the company Smith and Feldman founded. “From a compliance attorney’s standpoint, that’s always a great sign.”

Nurturing a penchant for compliance and dedicating a company legal and compliance department to pursuing it became a factor in Palladium’s decision to become involved with the company, Feldman said.

The focus on compliance also spread to the way Fora Financial brings brokers on board, Smith said. The company scrutinizes potential partners carefully before taking them on, he maintained.

“We probably missed out on some business as the industry grew because we were more cognizant of doing things the right way, but that paid off in the long run and some of our competitors have followed suit,” Smith said.

Compliance first became particularly important when Fora Financial added small-business loans to their initial business of providing merchant cash advances. They began making loans because lots of businesses don’t accept cards, which serve as the basis for cash advances.

On a cash basis, the current portfolio is 75 percent to 80 percent small-business loans. Loans started to surpass advances during the fourth quarter of 2014. The shift gained momentum after the company began funding through its bank sponsor, Bank of Lake Mills, in the third quarter of 2014.

Growth of loans will continue to outstrip growth of cash advances because manufacturers, construction companies and other businesses usually don’t accept cards, Smith said. If a customer qualifies for both, Fora Financial helps decide which makes the most sense in a specific case, Feldman added.

“We don’t sell our loans – we carry everything on the balance sheet and assume the risk,” Feldman said. “If it’s not good for the customer, it’s going to come back and hurt the performance of our portfolio over time,” he noted.

That thinking helped the company recognize the importance of adding loans to the mix. “We were one of the first companies (in the alternative-finance industry) to get our California lending license,” Feldman said. The company obtained the license in 2011 and got to work on lending. Offering loans required some retooling because the underwriting criteria differ so much from those in the cash advance business, Feldman said.

With the help of several law firms, they made sense of regulation from state to state and began offering the loans one state at a time, Smith said. “We wanted to make sure we rolled it out the right way,” Feldman noted.

As the company was changing, Smith and Feldman saw a need to rebrand. Initially, they called their company Paramount Merchant Funding to reflect their merchant cash advance offerings. When they added small-business loans to the mix, they used several additional names. Now, they’ve brought both functions and all of the names together under the Fora Financial brand. Fora means marketplace in Latin and seems broad enough to cover products the company might add in the future, Feldman said.

Smith and Feldman are contemplating what form those future products might take, but they declined to mention specifics. “We’re constantly getting feedback from customers on what they need that we’re not currently delivering,” Feldman said. “We have ideas in the pipeline.”

Despite changes in the business, Smith and Feldman have managed to remain true to timeless values in their personal lives. Smith grew up near Philadelphia in Fort Washington, Pa., and Feldman is a native of Roslyn, N.Y. Both now reside in Livingston, N.J. and occasionally ride the train together to work in New York. Smith is married and has two children, while Feldman and his wife recently had their first child.

“We’re at it everyday,” Feldman said of their work-oriented lifestyle. “When we’re out of the office, we’re traveling for work. So is the rest of the team. We’re only going to go as far as our people.”

And what about that other pair luxuriating in the Caribbean? As Feldman put it: “New Jersey is a long way from Puerto Rico.”

—

Learn more about Fora Financial at www.forafinancial.com

Meet Fora Financial’s Co-founders Jared Feldman and Dan Smith

February 5, 2016Entrepreneurs Jared Feldman and Dan Smith launched their company Fora Financial in 2008. Today it has placed more than $400 million in funding through 14,000 deals. Late last year, they sold part of their company to Palladium Equity Partners LLC for an undisclosed sum, but it is rumored to be quite sizable. It’s almost by coincidence that they named their company “Fora,” which means marketplace in latin, years before “marketplace lending” would become an industry buzzword.

Palladium, which describes itself as a middlemarket investment firm, decided to make the deal partly because it was impressed by Smith and Feldman, according to Green. “Jared and Dan have a passion for supporting small businesses and built the company from the ground up with that mission,” he said. “We place great importance on the company’s management team.”

The Palladium deal marked a milestone in the development of Fora Financial, a company with roots that date back to when Smith and Feldman met while studying business management at Indiana University. After graduation, Feldman landed a job in alternative funding in New York at Merchant Cash & Capital (today named BizFi), and he recruited Smith to join him there. “That was basically our first job out of college,” Feldman said.

It struck Smith as a great place to start. “It was the easiest way for me to get to New York out of college,” he said. “I saw a lot of opportunity there.”

The pair stayed with the company a year and a half before striking out on their own to start a funding company in April 2008. “We were young and ambitious,” Feldman said. “We thought it was the right time in our lives to take that chance.”

The full 4-page featured story appears in deBanked’s January/February 2016 issue.

Subscribe FREE

to make sure you get it!

Industry Trade Group Coming of Age: The SBFA is Becoming More Political

February 1, 2016By hiring an executive director, the Small Business Finance Association hopes to achieve at least two goals – taking a step toward becoming a full-service trade group and providing a public voice for the alternative finance industry.

Stephen Denis, formerly deputy staff director of the U.S. House Committee on Small Business, went to work in the new role in mid-December, setting up shop with his cell phone and laptop in a Washington, DC, area coffee emporium. He’s the SBFA’s first full-time employee.

Hiring Denis, who also has association experience, represents “the next evolution” of the trade group, according to David Goldin, SBFA president and Capify’s founder, president and CEO.

The SBFA, which got its start in 2008 as the North American Merchant Advance Association, changed its name last year because members have added small-business loans to the their merchant cash advance offerings. Although the trade group’s not exactly new, it has plenty of room to grow and its leadership and members seem open to change.

The SBFA, which got its start in 2008 as the North American Merchant Advance Association, changed its name last year because members have added small-business loans to the their merchant cash advance offerings. Although the trade group’s not exactly new, it has plenty of room to grow and its leadership and members seem open to change.

“The goal is to start from scratch and take a look at everything the association is doing,” Denis told deBanked, “and to really build this out to a robust group that represents the interests of small businesses.”

Denis appears optimistic about pursuing that goal. He’s a native of the Boston area and a Harvard University graduate whose first job out of school was as an aide to Republican Sen. John E. Sununu of New Hampshire. After three years in that position, he took a job for two years with a UK-based trade association, traveling frequently to London to inform the group of Congressional action in the United States.

From there, Denis went on to become director of government affairs and economic development for the Cincinnati Business Committee, a regional association that included Fortune 500 companies among its members. After two years in that role, Denis joined the staff of Rep. Steve Chabot, R-Ohio, moving back to Washington and serving as the congressman’s deputy chief of staff during a five-year stint that ended when he joined the SBFA.

While working for Chabot, Denis also became deputy staff director of the House Committee for Small Business, the No. 2 position there, and he has held that job for the last three years. The committee’s tasks include learning as much as they can about small business, including financing, and using the information to advise members of the House on policy initiatives.

The experience Denis has amassed in government should serve the association well because his duties include briefing federal legislators and regulators on how the alternative-finance business works. With Denis as spokesperson, the industry can speak to government with a single voice, Goldin asserted.

“We are going to be aggressive in our outreach to legislators and regulators as well as be active reaching out to local, state governments,” Denis said. The SBFA will “work with other trade groups and small business groups to promote our mission to ensure small businesses have alternative finance options available to them.”

Until now, too many players from the alternative finance industry have been vying for lawmakers’ attention, Goldin said. To make matters worse, some of those seeking to influence government in hearings on Capitol Hill are brokers instead of lenders and thus may not have a perfect understanding of risk and other aspects of the business, he maintained.

“We’re hearing that there are people trying to be the voice of small-business finance that either don’t have a lot of years of experience or they’re not telling the whole story,” Goldin said. “We want to make sure the industry’s represented properly.”

Denis can draw attention away from the “noise” created by unqualified voices and focus on information that Congress needs to make reasonable decisions about the alternative finance business, Goldin maintained.

Besides getting the word out in Washington, the SBFA hopes to convey its message to the general public on “the benefits of alternative financing,” Goldin said. At the same time the group can help make small business owners aware of the finance options, Denis added.

Asked whether hiring Denis marks the beginning of an effort to lobby members of Congress for legislation the association deems favorable to the industry, Goldin said only that additional announcements will be forthcoming.

Asked whether hiring Denis marks the beginning of an effort to lobby members of Congress for legislation the association deems favorable to the industry, Goldin said only that additional announcements will be forthcoming.

Meanwhile, updated “best practices” guidelines might be in the offing to help industry players navigate the business ethically and efficiently, Goldin said. A set of six best practices the association released in 2011 included clear disclosure of fees, clear disclosure of recourse, sensitivity to a merchants’ cash flow, making sure advances aren’t presented as loans and paying off outstanding balances on previous advances.

Addressing other possible steps in the association’s growth, Goldin said the group doesn’t plan to publish an industry trade magazine or newsletter. However, a trade show or conference might make sense, he noted.

Denis said he and the board had not discussed the possibility of a test, credential or accreditation to certify the expertise of qualified members of the industry. However, associations often establish and monitor such standards, so it would be reasonable for the SBFA to do so, he added.

The association might establish a Washington office, Goldin said. “We’ll look to Steve for his thoughts and guidance on that,” he observed. Denis seems amenable to the idea. “Down the road, we would love to open an office and hire more people,” he said.

In Goldin’s view, all of those moves might help the rest of the world comprehend the industry. Understanding the industry requires taking into account the cost of dealing with risk and business operations, he said.

Placing a $20,000 merchant cash advance, for example, requires a customer-acquisition effort that costs about $3,000 and a write-off of losses and overhead of about $4,000, Goldin said. That’s a total of $27,000 even without the cost of capital, he maintained.

“Most people don’t understand the economics of our business,” Goldin continued. The majority of placements are for less than $25,000, he said, characterizing them as “almost a loss leader when you factor in the acquisition costs.”

While spreading that type of information on the industry’s inner workings, Denis will also conduct the day-to-day for the not-for-profit’s affairs. The association’s board of directors will continue to set policy and objectives.

Members elect the board members to two-year terms. Current board members are Goldin; Jeremy Brown of Rapid Advance, who’s also serving as the group’s vice president; John D’Amico, GRP Funding; Stephen Sheinbaum, Bizfi; and John Snead, Merchants Capital Access.

Member companies include Bizfi, BFS Capital, Capify, Credibly, Elevate Funding, Fora Financial, GRP Funding, Merchant Capital Source, Merchants Capital Access (MCA), Nextwave Funding, NLYH Group LLC, North American Bancard, Principis Capital, Rapid Advance, Strategic Funding Source and Swift Capital.

Companies pay $3,000 in monthly dues, which Denis characterizes as inexpensive for a DC-based trade association.

Membership could spread to other types of businesses, Denis said. “I’d like to expand the tent to other industries,” he noted. “The association is trying to represent the interests of small business and make sure they have every finance option available to them.”

But a key purpose of the trade association is to provide a forum for members to come together as an industry, Denis said. “We’re thinking big,” he admitted. “We hope that all members of the marketplace will want to become a part of it.”

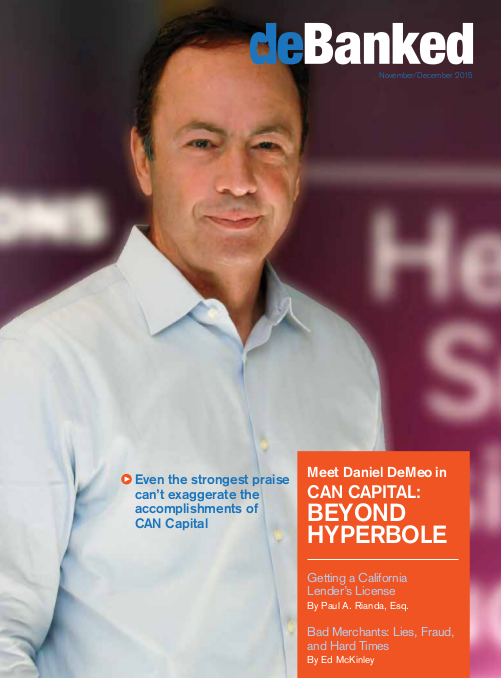

CAN Capital: Beyond Hyperbole

December 11, 2015 It’s usually risky to say “first,” “largest” or “best,” but CAN Capital invites those superlatives and more.

It’s usually risky to say “first,” “largest” or “best,” but CAN Capital invites those superlatives and more.

Asked whether the company’s the biggest in the alternative funding business, CEO Dan DeMeo hedges only a little with qualifiers like “might” or “probably” before proudly announcing that the company has provided access to more than $5.5 billion in working capital through 163,000 fundings to merchants operating in over 540 different kinds of businesses.

Glenn Goldman, the company’s CEO from 2001 to 2013 and now Credibly’s chief executive, doesn’t mince words about his former employer when he calls CAN Capital the biggest and most profitable small business alternative finance company in the U.S.

Cofounder and Chairman Gary Johnson proclaims without hesitation that CAN Capital was the first alternative small business finance company. His wife and cofounder, Barbara Johnson, came up with the idea of the Merchant Cash Advance in 1998 when she had trouble raising funds to promote her business, he said.

CAN Capital developed the first platform to split card receipts between the merchant and funder, and it gave birth to the idea of daily remittances, Johnson continued. Within a few years of its founding the company was turning a profit, another first in alternative finance, he claimed.

The innovation continued from there, according to Andrea L. Petro, executive vice president and division manager of Lender Finance, a division of Wells Fargo Capital Finance. She cited a couple of possible firsts she’s witnessed in her dealings with CAN Capital.

When CAN Capital received a loan from Wells Fargo in 2003, it may have been the first sizeable placement in the alternative finance industry by a major traditional financial institution, Petro said. In 2010, CAN Capital was among the first alternative funders to offer direct loans, she noted.

Petro stopped short of characterizing CAN Capital as the best in the alternative finance business, but she praised the company’s management and lauded its systems for underwriting and monitoring funding. “They continually upgrade their systems, upgrade their software, upgrade their people,” she said.

Calling CAN Capital one of the best comes naturally to Kevin Efrusy, a partner at Accel Partners and a CAN Capital board member. Accel saw opportunity in alternative finance because banks were reluctant to lend at the same time that an explosion of data on small businesses was informing the underwriting process. When Accel sought a position in the industry, it contacted CAN Capital, he said.

“Frankly, CAN Capital didn’t need or want our money,” Efrusy said. “We approached them.” Five years ago, Accel convinced CAN Capital that additional resources could help the company grow, and it bought a stake in the company.

With so many extolling the virtues of CAN Capital, deBanked asked DeMeo for a look at the thinking that underlies the success.

PLOTTING STRATEGY

CAN Capital pursues a strategy that DeMeo visualizes as a honeycomb. In the center cell, he places the objective of “helping small businesses succeed.” The compartmental element above that provides a place for the goal of serving as “the preferred provider of financial solutions to small business,” he said. The company’s cultural values, summarized as “Care, Dare and Deliver,” reside in the compartment below the center cell as table stake underpinnings, he added.

DeMeo also describes the company as driven by four strategic planks: “1) Expand the market, 2) broaden the product set, 3) deepen relationships with customers, and 4) achieve operating excellence,” he said.

What does success look like to the company? To DeMeo, it’s dramatic growth in the number of customers, resulting in increased revenue, a more valuable company and better career opportunities. “Digital automation and customer experience are at the center of those efforts,” he said.

CAN Capital operates with a “huge appetite for ‘test and learn,’” according to DeMeo. “That’s how we keep innovation alive,” he said.

And the result of all that? The company has increased fundings by 29 percent (CAGR) and revenue by 24 percent (CAGR), with corresponding growth in earnings, DeMeo said. It has also grown its digital business by 600 percent since 2014, he noted.

AT THE WHEEL

AT THE WHEEL

DeMeo, the man at the top of CAN Capital, joined the company in 2010 as chief financial officer and became CEO early in 2013. He was previously CFO at 1st Financial Bank, and also served as CFO for JP Morgan Chase’s consumer and small business unit. DeMeo also was chief marketing officer and ran business development head for GE Capital’s consumer card unit. His career began at Citibank, where he held senior roles in marketing and customer analytics.

“I was very fortunate to work for some pedigree companies earlier in my career,” DeMeo said. “Those companies emphasized market based training and development, and I worked with very smart and hardworking people. I also had great experience in unsecured lending.” His formative years left him with great appreciation for “behavioral analytics and the quantitative, information-based approach to business finance.”

Experience convinced him, as a CEO, the importance of attention to the balance sheet and income statement. It’s vital to combine that with innovation and growth orientation, DeMeo said. He seeks to lead, inspire and motivate employees, he emphasized.

DeMeo grew up in Atlantic City, NJ, with parents who valued hard work, education and maximizing opportunity. His wife and three children have supported him in his career despite the long hours and dedication necessary for success.

At CAN Capital DeMeo has faced the challenge of managing the business through internal and external cycles. Running the company often comes down to balancing what customers want with what makes economic sense, he said. “Pigs eat, and hogs get slaughtered,” he maintained. “You can’t get too greedy.”

DeMeo runs the company without the help of a President or Chief Operating Officer. While DeMeo serves as the public face of the company, he also devotes himself to every aspect of operations, he said.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Although CAN Capital’s drive for technological innovation and its measured approach to fundings have remained constant, the company has renamed itself several times to fit changing times.

In November 2013, it rebranded itself publicly as CAN Capital, and the company now provides access to business loans through CAN Capital Asset Servicing Inc, and Merchant Cash Advances through CAN Capital Merchant Services.

With the CAN Capital rebranding, it dropped the umbrella name of Capital Access Network. At the same time, it retired the AdvanceMe, New Logic Business Loans and CapTap names.

Most of the company’s old names applied to products or distribution channels, DeMeo said. The company had added them when it presented a new product, such as loans, or introduced a way of going to market, like end-to-end digital technology.

Consolidating the names reflected the company’s decision to put its direct marketing efforts on equal footing with business generated by partner companies, DeMeo said. Having just one name would result in a more efficient approach to building a stronger brand, he noted.

“The opportunity is to create one brand, multiple products and omni channel distribution under one company,” he said. “For a company our size, it would be hard to create brand awareness if you had to put significant promotional support behind every one of those sub brands.”

CAN Connect is a sub-brand that has survived. “That’s not a product name or distribution channel name,” DeMeo said. “It’s the technology suite we use to connect with partners so that we can exchange information in real time.”

CAN Connect is a way to speed up the process and eliminate friction for customers and partners. For example, a partner is able to link their CRM directly into CAN Capital’s decision engine, eliminating manual steps in submitting and generating offers. For partners with a customer-facing portal, CAN Connect enables an offer to be made available in real time to a small business owner, taking advantage of data sharing APIs to tailor the marketing message to fit the prospective customer’s needs.

Attention to detail pays off in repeat business for CAN Capital, in DeMeo’s view. “Almost 70% of our merchants return for another contract,” he said

THE GENESIS

By all accounts, CAN Capital is a company born of necessity. Barbara Johnson, who had the brainstorm that became CAN Capital, was running four Gymboree playgroup franchises in Connecticut and needed funds to finance summertime direct marketing efforts for fall enrollment.

But her company didn’t have much in the way of assets to pledge, so banks weren’t interested in providing funds. Why, she reasoned, couldn’t she just borrow or receive an advance against the credit card receipts she knew would flow in when the kids came back in the autumn? Thus, she gave birth to an industry.

Barbara Johnson and her husband, direct marketing executive Gary Johnson, cofounded the company as Countrywide Business Alliance and put up their own money to build a computerized platform to split card revenue, Gary Johnson said.

Then they persuaded a card processor to partner with them. Once they were operating and had signed their first customer, venture capital began flowing their way to grow the business. These days, the Johnsons remain major shareholders.

“What made it an interesting concept was how huge the market potential was,” Gary Johnson said. “That’s what the attraction still is today.” Although Merchant Cash Advances may now seem commonplace, they were startling at first, he said. “When we first went out in the marketplace, everybody thought it was a crazy idea,” he noted.

The company earned patents on processing related to Merchant Cash Advances and daily remittances, Gary Johnson said. At first, the patents deterred potential competitors from entering the business, but the company was unable to defend the patents successfully in court. Rivals then entered the fray.

Just the same, the company became profitable early on through “deliberate decision-making, having the right people in place and being bigger than everybody else,” he said.

Much of the company’s early business came through firms that provide merchants with transaction services, and that remains the case today, DeMeo said. Many were placing point of sale terminals in stores and restaurants to accept credit cards, and working capital became an upsell or cross-sell, he noted.

The large base of business CAN Capital built with merchant services companies means it will always be an important channel for the company. Recently, new merchant sign-ups have come from more diverse channels, including cobranded and referral partners, and the fast-growing direct marketing channels.

From the beginning, the merchants receiving capital used it to grow their businesses, DeMeo said. “That feeds the whole economic system and creates jobs,” he said.

TODAY’S NUTS AND BOLTS

TODAY’S NUTS AND BOLTS

Daily remittances give CAN Capital nearly constant insight into how well customers are performing, which enables the company to discover potential issues quickly and take action. Such close monitoring also provides the company with enough information to enable funding opportunities that competitors might pass up, DeMeo said.

“The basis for our decisions is how the business performs and business-specific indicators, such as capacity and consistency, versus looking at the personal credit history of the business owner,” DeMeo noted.

Having that data also helps the company create models it can use to serve other businesses in the same classification, DeMeo said. “It’s poured into machine learning for future decisioning,” he maintained. “It’s a cool concept, right?”

The company’s 450 or so employees work in several locations. Three hundred of the total are attached to the office in Kennesaw, GA, the region where the company first set up operations. To this day, that’s where the company conducts most of its business, DeMeo said.

About 25 employees work in technology and operating support in offices in Salt Lake City because the area offers a strong talent pool and provides the company with additional time zone coverage, DeMeo said.

Some of the company’s former executives came from Western Union, which had a presence in Costa Rica. About a hundred employees are now stationed there, working on technology, maintenance and development. That location also houses back-office redundancy for the company, too.

On Manhattan’s 14th Street, the company has 30 or so employees, who include digital engineers, marketing and business development teams, the human resources lead, the chief financial officer, the chief legal officer, and the chief executive officer. The company moved its executive office there from Scarsdale, NY to take advantage of the digital boom, he said, adding that, “Google’s right around the corner.”

On Manhattan’s 14th Street, the company has 30 or so employees, who include digital engineers, marketing and business development teams, the human resources lead, the chief financial officer, the chief legal officer, and the chief executive officer. The company moved its executive office there from Scarsdale, NY to take advantage of the digital boom, he said, adding that, “Google’s right around the corner.”

Compared with most companies in alternative finance, CAN Capital has little venture capital as part of its ownership structure, DeMeo said. “It’s a self-sustaining business. We’re not forced to approach the capital market to cover our burn rate. We’re cash-flow positive.” Competitors have to borrow to fund their growth, he noted.

The company has taken on infusions of debt financing, not equity financing. In the latter, a company is selling part of itself, DeMeo said. “We raised $650 million from a syndicate with five new banks and 10 banks in total.” The company completed a securitization of $200 million the year before, he said.

CAN Capital recently introduced the new TrakLoan product that has no fixed maturity date, with daily payments that are based on a fixed percentage of card receipts. This way, payments ebb and flow with the merchant’s card sales. CAN Capital is also testing “bank-like” installment loans of as much as $500,000 with a payback period of up to four years.

And there’s nowhere to go but up, in the view of CAN Capital executives. With a market of 28 million small American merchants and penetration of between 5 and 10 percent, they see plenty of potential to keep earning superlatives.

Bad Merchants: Lies, Fraud, and Hard Times

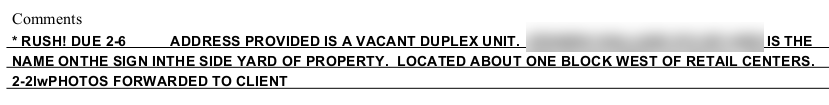

December 4, 2015 Critics seldom tire of bashing alternative finance companies, but bad behavior by merchants on the other side of the funding equation goes largely unreported. Behind a veil of silence, devious funding applicants lie about their circumstances or falsify bank records to “qualify” for advances or loans they can’t or won’t repay. Meanwhile, imposters who don’t even own stores or restaurants apply for working capital and then disappear with the money.

Critics seldom tire of bashing alternative finance companies, but bad behavior by merchants on the other side of the funding equation goes largely unreported. Behind a veil of silence, devious funding applicants lie about their circumstances or falsify bank records to “qualify” for advances or loans they can’t or won’t repay. Meanwhile, imposters who don’t even own stores or restaurants apply for working capital and then disappear with the money.

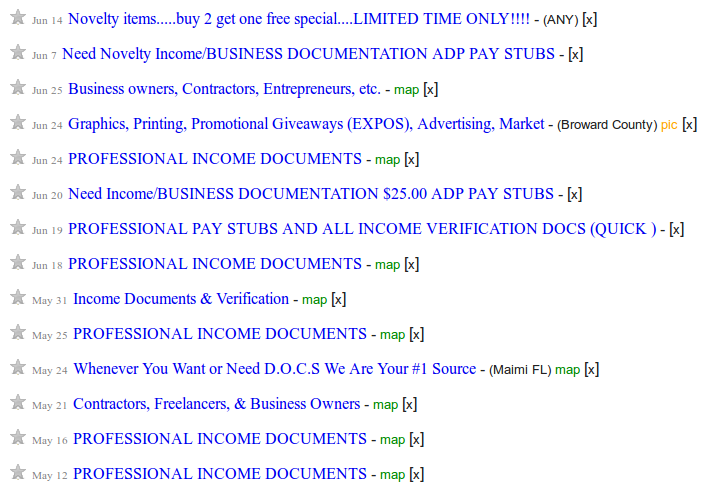

“People advertise on craigslist to help you commit fraud,” declared Scott Williams, managing member at Florida-based Financial Advantage Group LLC, who helped start DataMerch LLC to track wayward funding applicants. “Fraud’s a booming business, and every year the numbers seem to increase.”

Deception’s naturally on the rise as the industry continues to grow, according to funders, industry attorneys and collections experts. But it’s also increasing because technology has made it easy for unscrupulous funding applicants to make themselves appear worthy of funding by doctoring or forging bank statements, observers agreed.

Some fraud-minded merchants buy “novelty” bank statements online for as little as $5 and fill them out electronically, said David Goldin, president and CEO of Capify, a New York-based funder formerly called AmeriMerchant, and president of the SBFA, which in the past was called the North American Merchant Advance Association.

To make matters worse, dishonest brokers sometimes coach merchants on how to create the forgeries or modify legitimate records, Goldin maintained. Funders have gone so far as to hire private investigators to scrutinize brokers, he said.

But savvy funders can avoid bogus bank statements, according to Nicholas Giuliano, a partner at Giuliano, McDonnell & Perrone, a New York law firm that handles collections. Funders can protect themselves by remaining skeptical of bank records supplied by applicants. “If the merchant cash advance company is not getting them directly from the source, they can be fooled,” Giuliano said of obtaining the documents from banks.

Another attorney at the firm, Christopher Murray, noted that many funders insist upon getting the merchant’s user name and password to log on to bank accounts to check for risk. That way, they can see for themselves what’s happening with the merchant.

Besides banking records, funders should beware of other types of false information the can prove difficult to ferret out and even more difficult to prove, Murray said. For example, a merchant who’s nine or ten months behind in the rent could convince a landlord to lie about the situation, he noted. The landlord might be willing to go along with the scam in the hope of recouping some of the back rent from a merchant newly flush with cash.

Merchants can also reduce their payments on cash advances by providing customers with incentives to pay with cash instead of cards or by routing transactions through point of sale terminals that aren’t integrated onto the platform that splits the revenue, said Jamie Polon, a partner at the Great Neck, N.Y.-based law firm of Mavrides, Moyal, Packman & Sadkin, LLP and manager of its Creditors’ Rights Group. A site inspection can sometimes detect the extra terminals used to reduce the funder’s share of revenue, he suggested.

In a ruse they call “the evil twin” around the law offices of Giuliano, McDonnell & Perrone, merchants simply deny applying for the funding or receiving it, Giuliano said. “Suddenly, the transaction goes bad, and they deny they had anything to do with it,” he said. “It was someone who stole the merchant’s identity somehow and then falsified records.”

In other cases, merchants direct their banks not to continue paying an obligation to a funder, or they change to a different bank that’s not aware of the loan or advance, according to Murray. They can also switch to a transaction processor that’s not aware of the revenue split with the funder. Such behavior earns the sobriquet “predatory merchant,” and they’re a real problem for the industry, he said.

Occasionally, merchants decide to stop paying off their loans or advances on the advice of a credit consulting company that markets itself as capable of consolidating debt and lowering payments, Giuliano said. “That’s a growing issue,” agreed Murray. “A lot of these guys are coming from the consumer side of the industry.”

The debt consolidator may even bully creditors to settle for substantially less than the merchant has agreed to pay, Murray continued. Remember that in most cases the merchants hiring those companies to negotiate tend to be in less financial trouble than merchants that file for bankruptcy protection, he advised.

“More often than not, they simply don’t want to pay,” he said of some of the merchants coached by “the credit consultants.” They pay themselves a hundred thousand a year, and everyone else be damned. You continue to see them drive Humvees.”

Merchants sometimes take out a cash advance and immediately use the money to hire a bankruptcy attorney, who tries to lower the amount paid back, Murray continued. However, such cases are becoming rare because bankruptcy judges have almost no tolerance for the practice and because underwriting continues to improve, he noted.

Still, it’s not unheard of for a merchant to sell a business and then apply for working capital, Murray said. In such cases, funders who perform an online search find the applicant’s name still associated with the enterprise he or she formerly owned. Moreover, no one may have filed papers indicating the sale of the business. “That’s a bit more common than one would like,” he said.

In other cases the applicant didn’t even own a business in the first place. “They’re not just fudging numbers – they’re fudging contact information,” said Polon. “It’s a pure bait and switch. There wasn’t even a company. It’s a scheme and it’s stealing money.”

Whatever transgressions the merchants or pseudo-merchants commit, they seldom come up on criminal charges. “It is extremely, extremely rare that you will find a law enforcement agency that cares that a merchant cash advance company or alternative lender has been defrauded,” Murray said. It happens only if a merchant cheats a number of funders and clients, he asserted. “Recently, a guy made it his business to collect fraudulent auto loans,” he continued. “That’s a guy who is doing some time.”

However, funders can take miscreants to court in civil actions. “We’re generally successful in obtaining judgments,” said Giuliano. “Then my question is ‘how do you enforce it?’ You have to find the assets.” About 80 percent of merchants fail to appear in court, Murray added. Funders may have to deal with two sets of attorneys – one to litigate the case and another to enforce the judgment. Even merchants who aren’t appearing in court to meet the charges usually find the wherewithal to hire counsel, he said.

Funders sometimes recover the full amount through litigation but sometimes accept a partial settlement. “Compromise is not uncommon,” noted Giuliano. Settling for less makes more sense when the merchant is struggling financially but hasn’t been malicious, said Murray.

To avoid court, attorneys try to persuade merchants to pay up, said Polon. “My job is to get people on the phone and try to facilitate a resolution,” he said of his work in “pre-litigation efforts,” which also included demand letters advising debtors an attorney was handling the case.

But it’s even better not to become involved with fraudsters in the first place. That’s why more than 400 funding companies are using commercially available software that detects and reduces incidence of falsified bank records, said a representative of Microbilt, a 37-year-old Kennesaw, Ga.-based consumer reporting agency that has supplied a fraud-detection product for nearly four years.

But it’s even better not to become involved with fraudsters in the first place. That’s why more than 400 funding companies are using commercially available software that detects and reduces incidence of falsified bank records, said a representative of Microbilt, a 37-year-old Kennesaw, Ga.-based consumer reporting agency that has supplied a fraud-detection product for nearly four years.

“Our system logs into their bank account and draws down the various data points, and we run them through 175 algorithms,” he said. “It’s really a tool to automate the process of transferring information from the bank to the lender,” he explained.

The tools note gross income, customer expenditures, loans outstanding, checks returned for non-sufficient funds and other factors. Funders use the portions of the data that apply to their risk models, noted Sean M. Albert, MicroBilt’s senior vice president and chief marketing officer.

Funders pay 25 cents to $1.25 each time they use MicroBilt’s service, with the rate based on how often they use it, Albert said. “They only pay for hits,” he said, noting that they don’t charge if information’s not available. Funders can integrate with the MicroBilt server or use the service online. The company checks to make sure that potential customers actually work in the alternative funding business.

MicroBilt is testing a product that gathers information from a merchant’s credit card processing statement to analyze ability to repay excessive chargebacks reflected in the statements could spell trouble, and seasonality in receipts should show up, he noted.

Additional help in avoiding problem merchants comes from the Small Business Finance Association, which maintains a list of more than 10,000 badly behaving funding applicants, said the SBFA’s David Goldin. The nearly 20 companies that belong to the trade group supply the names.

SBFA members, who pay $3,000 monthly to belong, have access to the list. According to Goldin, the dues make sense because preventing a single case of fraud can offset them for some time, he maintained. Besides, associations in other industries charge as much as $10,000 a month, he added.

Another database of possibly dubious merchants, maintained by DataMerch LLC, became available to funders in July, according to Scott Williams, who started the enterprise with Cody Burgess. It became integrated with the deBanked news feed by early October, causing the number of participating funders to double to a total of about 40, he said. The service is free now, but will carry a fee in the future.

It’s not a blacklist of merchants that should never receive funding again, Williams emphasized. Businesses can return to solvency when circumstances can change, he noted. That’s why it’s wise to regard the database as an underwriting tool. In addition, merchants can in some cases add their side of the story to the listings.

Funding companies directly affected by wayward merchants can contribute names to the list, Williams said. About 2,500 merchants made the list within a few months of its inception, he noted. “We’re super happy with our numbers,” he said of the database’s growth.

Many merchants find themselves in the database because of hard times. Of those who land on the list because of fraud, perhaps 75 percent actually own businesses and about 25 percent are con artists applying for funding for shell companies, Williams said.

So far, only direct funders – not brokers or ISOs – can get access to the database, he continued, noting that DataMerch could rethink the restriction in the future. “We don’t want hearsay from a broker who might not know the full scope of the story,” he said.

DataMerch might grant brokers and ISOs the right to read the list to avoid wasting time pitching deals to substandard merchants, but the company does not intend to enable members of those groups to add merchants to the database, Williams said.

Williams sees a need for the new database because smaller companies can’t afford belonging to the SBFA. The association also tracks deals about to become final, which could prevent double-funding but makes some users uncomfortable because they don’t want to disclose their good merchants, Williams said.

Although dishonesty’s sometimes a factor, merchants often go into default just because of lean times, Jamie Polon, the attorney, cautioned. A restaurant could close, for example, because of construction or an equipment breakdown. “Were they not serving dinner anymore, or was there something much deeper going on?” he said. Fraud may play a role in 10 percent to 20 percent of the collections cases his law firm sees, he noted. More than 95 percent blame their troubles on a downturn in business, and the rest claim they didn’t understand the contract, he said.

Although dishonesty’s sometimes a factor, merchants often go into default just because of lean times, Jamie Polon, the attorney, cautioned. A restaurant could close, for example, because of construction or an equipment breakdown. “Were they not serving dinner anymore, or was there something much deeper going on?” he said. Fraud may play a role in 10 percent to 20 percent of the collections cases his law firm sees, he noted. More than 95 percent blame their troubles on a downturn in business, and the rest claim they didn’t understand the contract, he said.

To understand the downturn, it’s important to amass as much information about the merchant as possible, said Mark LeFevre, president and CEO of Kearns, Brinen & Monaghan, a Dover, Del.-based collections agency that works with funders. That information sheds light on a merchant’s ability to repay and could help determine what terms the merchant can meet, he said.

Timeliness matters because the sooner a creditor takes action to collect, the greater the chance of recouping all or most of the obligation, LeFevre maintained. When distress signals arise – such as closing an ACH account or a spate of unreturned phone calls – it’s time to place the merchant with a collections expert, he advised.

LeFevre’s company also traces a troubled merchant’s dwindling assets to help the funder receive a fair share. Funders can sometimes recover all or most of what they pay a collection agency by imposing fees on the merchant, he noted.

Pinning the collection fees to merchants in default makes sense because that’s where the guilt often resides, observers said. It’s part of balancing the bad behavior equation, they agreed.

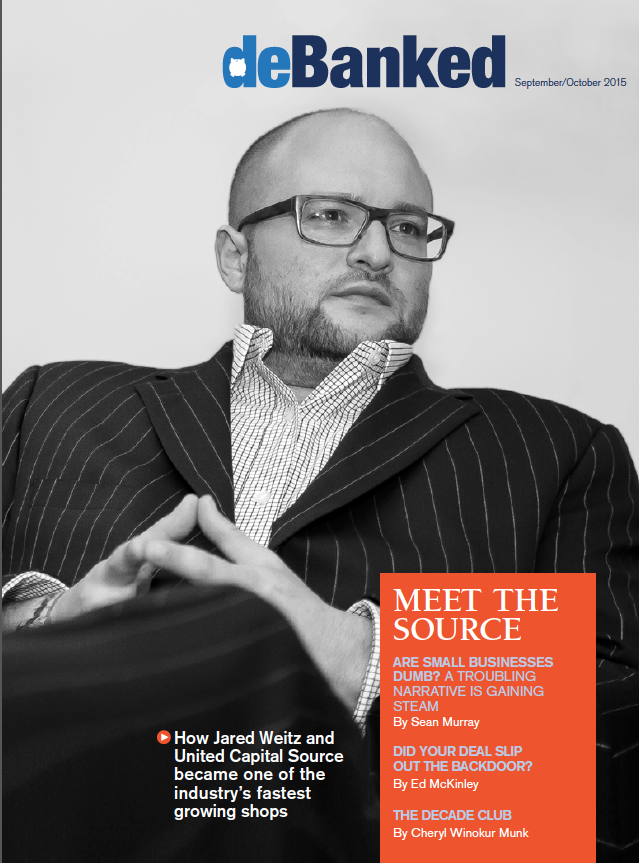

Meet the Source: How Jared Weitz and United Capital Source became one of the industry’s fastest growing shops

October 23, 2015Jared Weitz came from humble beginnings and nearly settled for a humble fate. But associates say an ordinary, uneventful life wouldn’t have suited him – he works too hard and figures things out too quickly.

Almost ten years ago Weitz, 33, was parking cars to earn money for community college. After finishing at St. Johns University, he almost made plumbing his career. But now he’s CEO of United Capital Source LLC, an alternative-finance brokerage with deal flow of between $9 million and $10 million a month and an annual growth rate of over 65 percent.

Business associates, former bosses and his small cadre of employees all seem to revere Weitz for his honesty and straightforwardness. They consider him a personal friend. They say he continues to grow as a businessman and as a human being while taking pleasure in helping others do the same.

Geographically, Weitz has the good fortune to know where he belongs – the city of New York is in his DNA. “Every time I fly back,” he said, “I’m so happy to land.”

His love affair with the city began in Brooklyn. He was born there and raised in a Brighton Beach apartment in the shadow of Coney Island. When he was 16, the family moved to Oceanside on Long Island.

As the second of six children, Weitz had to come up with the money for college on his own. “My older sister and I had to pay our way,” he said. “Everybody else, my dad was able to cover.” He started school at Nassau Community College, selling cell phones and parking cars at night.

But then came an abrupt change. Once Weitz saved enough money, he transferred to Tulane University in New Orleans to pursue a relationship with a woman who was finishing her studies there. He attended classes part-time, worked as the athletic director at the Jewish Community Center, tended bar in a Mexican restaurant and served summonses for a law firm.

But then came an abrupt change. Once Weitz saved enough money, he transferred to Tulane University in New Orleans to pursue a relationship with a woman who was finishing her studies there. He attended classes part-time, worked as the athletic director at the Jewish Community Center, tended bar in a Mexican restaurant and served summonses for a law firm.

The relationship with the woman fizzled, but Weitz made lasting friendships during his days down south. His old roommate in New Orleans, who now practices law in Atlanta, serves as counsel for United Capital Source.

When Weitz had been in New Orleans for two years, Hurricane Katrina struck. He evacuated to Houston, where he stayed in a Holiday Inn for two weeks before realizing he wouldn’t be able to return to southern Louisiana anytime soon. The magnitude of the devastation was just too great.

Shouldering the duffel bag of belongings he had managed to pack on his back during the evacuation, he returned to New York, enrolled in St. John’s University and began working in sales for Honda Financial Services and parking cars.

Weitz had started school expecting to become a teacher. He had grown up with younger siblings and liked leadership roles, which convinced him teaching would be a good fit.

Still, many of his college jobs had required him to sell. As a bartender, for example, he promoted drink specials. As an athletic director he convinced people to sign up for classes. “Everything that I took to naturally wound up being in the sales, marketing and finance arena,” Weitz observed.

When he was nearly finished at St. John’s, Weitz was parking a car for an acquaintance who offered him a job as a union plumber. Suddenly, he was making $27 an hour and had health benefits. “It was a big breather for me,” Weitz recalled.

He quit his three jobs and labored as a plumber from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. School started at 3:30 p.m. for him and stretched into the evening. But when he finished his degree, working as a teacher for $35,000 to $40,000 a year no longer seemed attractive.

Besides, his plumbing work didn’t center on toilets. On typical commercial plumbing jobs he did things like install air, medical and gas lines in hospitals. He was reading blueprints and bidding for jobs. A promotion to foreman didn’t seem that far off.

At about the same time, near the end of 2006, a friend, Mike Caronna, landed a job at Bizfi, formerly known as Merchant Cash and Capital (MCC), The company, which had just started and had only a few employees, was looking for underwriters.

As fate would have it, Weitz fell into a conversation with a fellow union plumber, one who had been on the job for 30 years. The older man reminded him that his wages would never climb much higher than they were right now. The veteran plumber then showed the younger man his hands, bent from decades of holding tools. “That got me thinking,” Weitz said.

He asked his friend Caronna to arrange a job interview at MCC. He got an offer and took a 90-day leave from his plumbing job to give the world of finance a try. “After about two weeks, I knew it was for me,” he said of the alternative-finance industry. It was by then the beginning of 2007.

Weitz excelled as an underwriter, and the company CEO, Stephen Sheinbaum, picked him and four others for a sales contest. Sheinbaum gave them some leads and turned them loose. Weitz won the competition but asked his boss to help him gain experience in business development and operations before taking on a sales position.

Sheinbaum was happy to comply. “He is one of the best and the brightest in the space,” he said of Weitz.

So, at age 25, Weitz found himself building a business development department by cultivating relationships with ISOs and persuading them to send business to MCC. “It was amazing,” he said of those days. “That was a big opportunity.”

Weitz learned the mechanics of the business. He found that the right ISO can originate good deals and a bad ISO can ruin deals. He learned the politics of when to talk, when to remain silent and when to let someone vent.

Then Weitz and a good friend at MCC, Anthony Giuliano – who’s now managing partner of Sure Payment Solutions – worked out how they could improve the MCC sales effort. They pitched Sheinbaum on the idea of having a second internal sale force, and that led to the birth of Next Level Funding (NLF), a division of MCC.

Weitz and Giuliano each owned 10 percent of NLF, and MCC owned 80 percent. “I’m 26, about to be 27, and I’m like, ‘You did it, Man,’” Weitz said as he looked back.

After about four months, NLF absorbed MCC’s original sales division. Next, Giuliano and another executive, Paul Giuffrida, decided to leave MCC. Weitz felt torn. He felt an allegiance to Giuliano and respected Giuliano’s knowledge of programming – a subject that was alien to him. Yet Sheinbaum had provided Weitz a series of opportunities.

Weitz stayed at MCC but felt he deserved to become chief sales officer. When that didn’t happen, he sold his shares back to the company at a dramatically reduced price to extricate himself from a non-compete clause and set off to start United Capital Source (UCS).

With a five-figure investment, Weitz and his then partner, started UCS in January of 2011 in a 250-square-foot office in Long Beach, L.I. Weitz invested about 90 percent of the money he had saved while working at MCC.

Jon Baum left NLF with Weitz and became the first UCS employee. Within a week or two, Danielle Rivelli, left NLF to join UCS, and Weitz put the remaining 10 percent of his savings into the business to meet the expanded payroll. Today, Baum and Rivelli are UCS sales managers.

Jon Baum left NLF with Weitz and became the first UCS employee. Within a week or two, Danielle Rivelli, left NLF to join UCS, and Weitz put the remaining 10 percent of his savings into the business to meet the expanded payroll. Today, Baum and Rivelli are UCS sales managers.

The first month UCS was open, it funded $240,000 in deals. “It just felt good to be on my own and start funding deals,” Weitz said. From the beginning of UCS, he won praise from funders for bringing them the right kind of deals with merchants who were likely to repay.

“He really has the pulse of the marketplace and what a lender is looking for,” said Todd Sherer, who handles business development for Entrepreneur Growth Capital. “He doesn’t waste time giving you transactions that don’t fit in your box.”

That’s because doing things right means a lot to Weitz. “He is one of the most straightforward, honest, high-integrity people I have met in the industry,” said Steven Mandis, adjunct associate professor at the Columbia University Business School and chairman of Kalamata Capital LLC.

He’s won the OnDeck seal of approval. “OnDeck has a rigorous and extensive background check process as part of our broker certification process,” said Paul Rosen, OnDeck’s chief sales officer. “Jared Weitz and United Capital have passed our screens and process and are currently active brokers for OnDeck.”

And with time, Weitz has learned patience. He was sometimes short with funders when he started his company but has matured into a pleasant person to deal with, said Heather Francis, CEO of Elevate Funding. “I’ve seen that growth with him,” she said.

All of those good qualities soon came together to help UCS succeed. Within four months of its launch, the company rented a 1,500-square-foot office in Garden City and hired two more people. Next came a 3,200-square-foot office in Rockville Centre and three more employees.

“The company was growing and gaining traction,” Weitz recalled. “I bought out my original partner.” Since then, Vincent Pappalardo has invested in UCS and become a minority partner.

Meanwhile, the lease was expiring on Long Island, and Weitz felt the time had come to move to Manhattan. That would enable the company to draw employees from throughout the region and not just Long Island.

“We decided to bite the bullet and pay the excess money to move to the city because we believed it would be better for the business,” Weitz said. He added two people and rented a 5,500-square-foot space near Penn Station in the Garment District in September of 2014.

Within three months of making the move to Manhattan, business doubled. “Being in a faster-paced environment caused the business to go through another growth phase,” he said. After nine months in the city, UCS is now taking over a whole 8,500-square-foot floor of the same building.

Within three months of making the move to Manhattan, business doubled. “Being in a faster-paced environment caused the business to go through another growth phase,” he said. After nine months in the city, UCS is now taking over a whole 8,500-square-foot floor of the same building.

UCS remains a small shop in terms of headcount with 21 people, but the company’s funding numbers equal the output of many brokerages five times its size. Twelve of the UCS employees work in sales, with the others engaged mainly in underwriting, operations and customer service.

Less than 2 percent of UCS’s funding volume comes from broker business. “We self-generate all of our business,” Weitz said, declining to elaborate too much on his company’s marketing efforts.

“My salespeople – bar none – are the best in the industry,” he claimed. “Much like the Navy has the SEALS and the Army has the Rangers, there are groups in the industry that can do triple or quadruple what other people do because that’s just the way they are.” His people fund an average of $750,000 per month per person in new business, while his renewals reps fund well into the 7-figure range per person.

UCS salespeople achieve their results because they have detailed knowledge of the industry, Weitz said. The staff’s understanding of alternative finance doesn’t end with sales but also includes underwriting and finance, he noted. “That’s what makes you a very good and knowledgeable sales rep,” he maintained.

His salespeople don’t just tell a client what he or she wants to hear. They take the time to understand the client’s financial situation. “They know how to read a profit and loss statement, a balance sheet and tax returns,” Weitz said.

ARE THE BEST IN THE INDUSTRY”

While 90% of Weitz’s sales team has a college degree, most of the salespeople have come from outside the industry, he said, noting that one was with Sleepy’s, the mattress company. Another was selling memberships at a gym, one worked for a credit card processing company, two were barbers and one had just graduated from college.

UCS doesn’t make double-digit commissions because the company isn’t over-charging merchants, Weitz maintained. The company does not obtain excess funding that a customer can’t afford or increase the factor rate to dangerous levels, he noted.

“You’re not really helping the merchant” by providing too much capital, Weitz asserted. “You’re sucking the blood out of him before he goes away. That’s not why I’m in business.”

A clean record will also prove beneficial when federal regulation comes to the industry, he said. Integrity in the workplace can also spill over into other parts of a person’s life, Weitz believes.

As UCS grew larger and Weitz grew older, he saw his employees rent their first apartments and then buy their first homes. He learned then that he had taken on more responsibility than was apparent to him at first.

As UCS grew larger and Weitz grew older, he saw his employees rent their first apartments and then buy their first homes. He learned then that he had taken on more responsibility than was apparent to him at first.

To accommodate the employees he added a human relations department and commissioned a company handbook. He’s also started marketing, finance, operations and other departments.

He’s lost only four employees because he pays them well, respects their time and doesn’t view their youth as a liability.

Meanwhile, talking daily to merchants and hearing about their heartaches and triumphs has humbled and matured Weitz. Seeing how the merchants’ choices panned out or fell short also shaped him and helped him grow up a little, he said.

Weitz has found time in his 70-hour workweek to meet his future bride. They’re planning to wed next year, and he plans to invite his entire staff. “It wouldn’t feel right without them,” he said.

Weitz has skipped the Ferrari, Rolls Royce and mansion because he didn’t feel he needed them. But even without those status symbols, it’s clear that Weitz has avoided settling for a humble fate.

As for what comes next, UCS is said to be developing an online marketplace to take their business to the next level, though Weitz declined to provide specific details about how it will work. “We’re on pace to do more than $100 million worth of deals a year,” Weitz said. “And as far as we’ve come, I feel like this is still just the beginning.”

Did Your Deal Slip Out The Back Door?

October 22, 2015Gil Zapata found himself in the right place at the right time to catch someone red-handed at backdooring, the practice of stealing an alternative-funding deal and cheating the original ISO or broker out of the commission.

It seems that Zapata, who’s president and CEO of Miami-based Lendinero, was sitting in a client’s office about three years ago when the phone rang. The call came from an employee of a direct funder that had turned down Zapata’s deal to fund the merchant. Now, the employee was offering funding from another source without notifying Zapata. Fortunately, the merchant didn’t accept the surreptitious funding, Zapata said. “There’s a huge loyalty factor with maybe 50 percent of the clients an ISO has under their belt,” he noted.

It seems that Zapata, who’s president and CEO of Miami-based Lendinero, was sitting in a client’s office about three years ago when the phone rang. The call came from an employee of a direct funder that had turned down Zapata’s deal to fund the merchant. Now, the employee was offering funding from another source without notifying Zapata. Fortunately, the merchant didn’t accept the surreptitious funding, Zapata said. “There’s a huge loyalty factor with maybe 50 percent of the clients an ISO has under their belt,” he noted.

But many merchants sign up for backdoor deals out of ignorance, callousness or desperation, and the problem seemed to gather momentum in the first quarter of this year, according to Cheryl Tibbs, owner of Douglasville, Ga.-based One Stop Funding LLC.

When Tibbs found herself the victim of backdooring a few months ago, the merchant’s loyalty to the ISO prevailed once again. “Because of the relationship we had with the merchant, he let us know and didn’t go along with it,” she said.

Both cases fall into one of the categories of backdooring. This type usually occurs when an ISO or broker submits a deal and the funder declines it, said John Tucker, managing member of 1st Capital Loans LLC in Troy, Mich. An employee of the funder then takes the file and offers it to other funders, often those that accept higher-risk deals. The funder’s employee conveniently forgets to include the originator in the commission, Tucker said. Meanwhile, the employee’s boss might know nothing of the post-denial goings-on.

In another variety of backdooring, ISOs or brokers deceptively claim that they’re direct funders. They solicit deals in online forums, by email message or over the phone, and then they offer the deals to companies that really do function as direct funders. In many cases, the fake funders pocket the entire commission, Tibbs said.

“I’m bombarded with probably 10 emails every day of the week from a supposedly new lender that wants my business, and they’re really just a broker shop like we are,” she maintained.

To guard against both kinds of backdooring, ISOs and brokers should know their funding sources, everyone interviewed for this article suggested. “What we’ve done is tighten up on how we do submissions,” Tibbs said. “We’re very particular about which lending platforms we use.” Although her company has contracts with 60 to 70 funders, it uses only three or four regularly, she noted. “Shotgunning” deals to lots of potential funders invites backdooring, Tibbs said.

To guard against both kinds of backdooring, ISOs and brokers should know their funding sources, everyone interviewed for this article suggested. “What we’ve done is tighten up on how we do submissions,” Tibbs said. “We’re very particular about which lending platforms we use.” Although her company has contracts with 60 to 70 funders, it uses only three or four regularly, she noted. “Shotgunning” deals to lots of potential funders invites backdooring, Tibbs said.

Tibbs also scrutinizes deals to determine which funder would provide the best fit. That way, fewer deals are declined and thus fewer became candidates for backdooring by unscrupulous funder employees. “We have a system. We scrub it. We do the numbers,” she said of her company’s close attention to underwriting, which helps determine what funders would accept the deal.

Her company also keeps a watchful eye on every deal’s progress. “We know exactly where the deal is, and who’s looked at it,” she said. It also helps to insist upon having a dedicated account rep, Tibbs emphasized. That way she can form a relationship that discourages backdooring.

Perhaps the most basic safeguard comes with determining that the company claiming to fund the deal really has the capital to do it and isn’t just shopping the file to real funders. Tucker advised using Internet searches to turn up evidence that the supposed funder really isn’t another ISO or broker. Searches should reveal press releases on equity rounds that direct funders have received, for example. If open-ended Web searches don’t produce satisfying results, check state registrations, he said.

ISOs and brokers can also prevent backdooring by avoiding sub-agent status, Tucker cautioned. “I don’t know why guys would want to be a broker to a broker,” who could steal commissions, he observed. One exception to the sub-agent problem comes with agents who are just entering the business and are receiving training from a broker, Tucker said. In another exception, sub-agents may find another broker has competitive advantages that aren’t easy to duplicate – like a $20,000 monthly marketing budget to generate sales leads, he continued. Or perhaps the other broker gets low base pricing from a funder that allows for reduced factor rates without sacrificing part of the commission.

Brokers and ISOs can also protect themselves from backdooring – and just in general – by maintaining their relationships with merchants, even those who’ve been denied funding from four or five sources, Zapata said. An increase in revenue or jump in credit worthiness can qualify them a few months later, and other brokers or funders may be soliciting them in the meantime, he said.

Brokers and ISOs can also protect themselves from backdooring – and just in general – by maintaining their relationships with merchants, even those who’ve been denied funding from four or five sources, Zapata said. An increase in revenue or jump in credit worthiness can qualify them a few months later, and other brokers or funders may be soliciting them in the meantime, he said.

Then there’s the possibility of collective action against backdooring. An association or some other entity representing the industry could compile a database of companies accused of backdooring, Tibbs said. “Just as there’s a black list of merchants that have been red-flagged from getting merchant cash advances, there should be some type of database of funders that frequently backdoor deals – that way, ISOs know to stay away from them,” she maintained.

The database would also prompt owners and managers of direct-funding companies to crack down on employees who use nefarious tactics, Tibbs continued, because the heads of companies would want to stay off the list.

But finding the financial support and staffing for such a database might prove difficult, according to Tucker. He noted that the card brands, such as Visa and MasterCard, maintain a match list of merchants barred from accepting credit cards. But the card brands have vast resources and a keen interest in the list, he said.

Requiring funders to pay to register might discourage ISOs and brokers from posing as funders, Tibbs suggested. But that, too, would require an infrastructure and would demand financial investment, sources said.

Still, everyone interviewed agreed that the industry should police itself with regard to backdooring instead of inviting federal regulators to enter the fray. “The federal government will mess with pricing without understanding every merchant can’t get low factor rates because there’s too much risk on the deal,” Tucker warned.

Perhaps extending the protection period in funding applications would help guard ISOs and brokers, Zapata said. But he cautioned that making the time period too long could interfere with the free market.

Keeping backdooring in perspective also makes sense, Zapata said, noting that merchants often receive multiple funding offers because everyone in the industry is basing phone calls on the same Uniform Commercial Code filings regarding distressed merchants.

Alternative Funding: Over The Top Down Under

September 2, 2015 San Francisco had its gold rush, Oklahoma had its land rush and now Australia is experiencing a rush of alternative funding. After a slow start a few years ago, foreign and domestic companies have been flocking to the market down under in the last 18 months.

San Francisco had its gold rush, Oklahoma had its land rush and now Australia is experiencing a rush of alternative funding. After a slow start a few years ago, foreign and domestic companies have been flocking to the market down under in the last 18 months.

As many as 20 new alt-funders are doing business in Australia, but that number could swell to a hundred, said Beau Bertoli, joint CEO of Prospa, a Sydney-based alternative funder. “The market in Australia has been very ripe for alternative finance,” Bertoli, said. “We see an opportunity for the alternative finance segment to be more dominant in Australia than it is in America.”

Recent entrants to the embryotic Australian market include Spotcap, a Berlin-based company partly funded by Germany’s Rocket Internet; Australia’s Kikka Capital, which gets tech backing from U.S.-based Kabbage; America’s Ondeck, which is working with MYOB, a software company; Moula, which began offering funding this year but considers itself ahead of the curve because it formed two years ago; and PayPal, the giant American payments company.