Lightspeed: ‘our largest use of cash will be growing our merchant cash advance business’

February 10, 2026 Lightspeed Capital originated $257M in merchant cash advances in the last 9 months of 2025, up from $207M over the same period in 2024. The company has repeatedly talked up the healthy profit margins earned on MCAs and last quarter called them a “super popular upsell.” Lightspeed operates in the POS and e-commerce space, competing against companies such as Shopify, Square, Toast, and Clover. Lightspeed Capital is its MCA business.

Lightspeed Capital originated $257M in merchant cash advances in the last 9 months of 2025, up from $207M over the same period in 2024. The company has repeatedly talked up the healthy profit margins earned on MCAs and last quarter called them a “super popular upsell.” Lightspeed operates in the POS and e-commerce space, competing against companies such as Shopify, Square, Toast, and Clover. Lightspeed Capital is its MCA business.

“Aside from potential buybacks, our largest use of cash will be growing our merchant cash advance business,” said Lightspeed CFO Asha Bakshani during the company’s recent quarterly earnings call. “There are currently $106 million in merchant cash advances outstanding, and we intend to continue to grow this high-margin business over time.”

Lightspeed MCAs are typically satisfied by merchants within seven months, but they want to shrink that timeframe even more. “Our goal is to target a shorter remittance time frame, and we are making great progress towards that end,” said Bakshani. The average factor rate is a 1.14.

Industry’s Mystery Fraudster Extradited to the United States

January 30, 2026A primary suspect in the small business finance industry’s long running mysterious fraud has been extradited to the United States. Saul Shalev, indicted this past August under seal (and unsealed in October) had eluded authorities for years but was finally arrested in Spain. On January 23, 2026, he was extradited to the United States and appeared before a US Magistrate Judge.

Shalev faces a nine-count indictment.

Between approximately December 2019 and November 2022, Shalev defrauded more than 20 small and medium-sized businesses (“SMBs”). As part of the scheme, Shalev obtained information about commercial loans received by the SMBs and offered the SMBs the opportunity to refinance the loans or to obtain additional financing, either from the original lender or from a new lender. Shalev, using stolen identities and making fraudulent representations, acted as a broker between SMBs and potential lenders. After obtaining new or additional financing for an SMB from a commercial lender, Shalev provided fraudulent payoff instructions to the SMB with respect to a prior loan, causing the SMB to send all or part of the loan proceeds to an account he controlled. Shalev also fraudulently received a commission from the lender.

No, Texas Did Not Ban Merchant Cash Advances

January 28, 2026 When Texas passed HB 700 last June, deBanked was among the first to point out that its most notable component was a prohibition on automatic debits of a recipient’s deposit account by a commercial sales-based financing provider unless they had a perfected first position. Some observers were quick to tell us that we had it all wrong, that MCAs had effectively been “banned” entirely and that we should have reported it that way. This was premised on a belief that perfecting a true first position on a recipient’s deposit account was a near-insurmountable obstacle (for MCAs that rely on ACHs instead of credit card splits) and thus a nuanced discussion of how to comply with the new law a moot debate.

When Texas passed HB 700 last June, deBanked was among the first to point out that its most notable component was a prohibition on automatic debits of a recipient’s deposit account by a commercial sales-based financing provider unless they had a perfected first position. Some observers were quick to tell us that we had it all wrong, that MCAs had effectively been “banned” entirely and that we should have reported it that way. This was premised on a belief that perfecting a true first position on a recipient’s deposit account was a near-insurmountable obstacle (for MCAs that rely on ACHs instead of credit card splits) and thus a nuanced discussion of how to comply with the new law a moot debate.

But if the state legislature had intended to ban sales-based financing outright, it simply could have done so. Instead, it codified a framework for how to legally provide sales-based financing. It provided guidance on registration, disclosure, and oversight. And it even went as far as to say that the Finance Commission of Texas cannot “adopt a maximum annual percentage rate, finance charge, or fee for commercial sales-based financing transactions.” This was an incredible signal: No cost cap on sales-based financing.

The Texas Office of Consumer Credit Commissioner (OCCC) even held an open forum this past November to hear from impacted parties on the best way to craft and enforce the rules going forward. And so while they’re now busy promulgating those precise rules, collective minds have returned back to the original language surrounding that “certain automatic debits” are “prohibited.”

CERTAIN AUTOMATIC DEBITS PROHIBITED.

A provider or commercial sales-based financing broker may not establish a mechanism for automatically debiting a recipient’s deposit account unless the provider or broker holds a validly perfected security interest in the recipient’s account under Chapter 9, Business & Commerce Code, with a first priority against the claims of all other persons.

This language does not say that merchants cannot pay sales-based financing providers entirely. Others agree. deBanked spoke with one company, MCA Pay, which analyzed what the law says and they created a tool for merchants to pay sales-based financing providers in an orderly easy manner so that funders do not in fact have to automatically debit a recipient’s deposit account at all. Though there are some layers to how it’s done, merchants are, on their own volition, setting up a system to initiate payments to whichever funder they choose. They’re in control.

Far from theoretical, this methodology is already being used by merchants in Texas to pay sales-based financing providers, according to MCA Pay.

“We’re comfortable from a regulatory perspective, but I encourage everybody who uses this platform to run this by their counsel,” a representative said. “We’re putting the control back into the merchant’s hands.”

The two main partners at MCA Pay, Gavriel Kalfa and Moshe Klar, do not hail from within the industry, but they worked with experienced operators in the industry while building out the system. MCA Pay is not the payments provider or a law firm, they’re just the platform that loops the pieces together.

“Hopefully we’ve made a product here that’s going to allow MCA to continue in Texas compliantly for everybody,” they said.

The Average MCA Deal? $58k Report Says

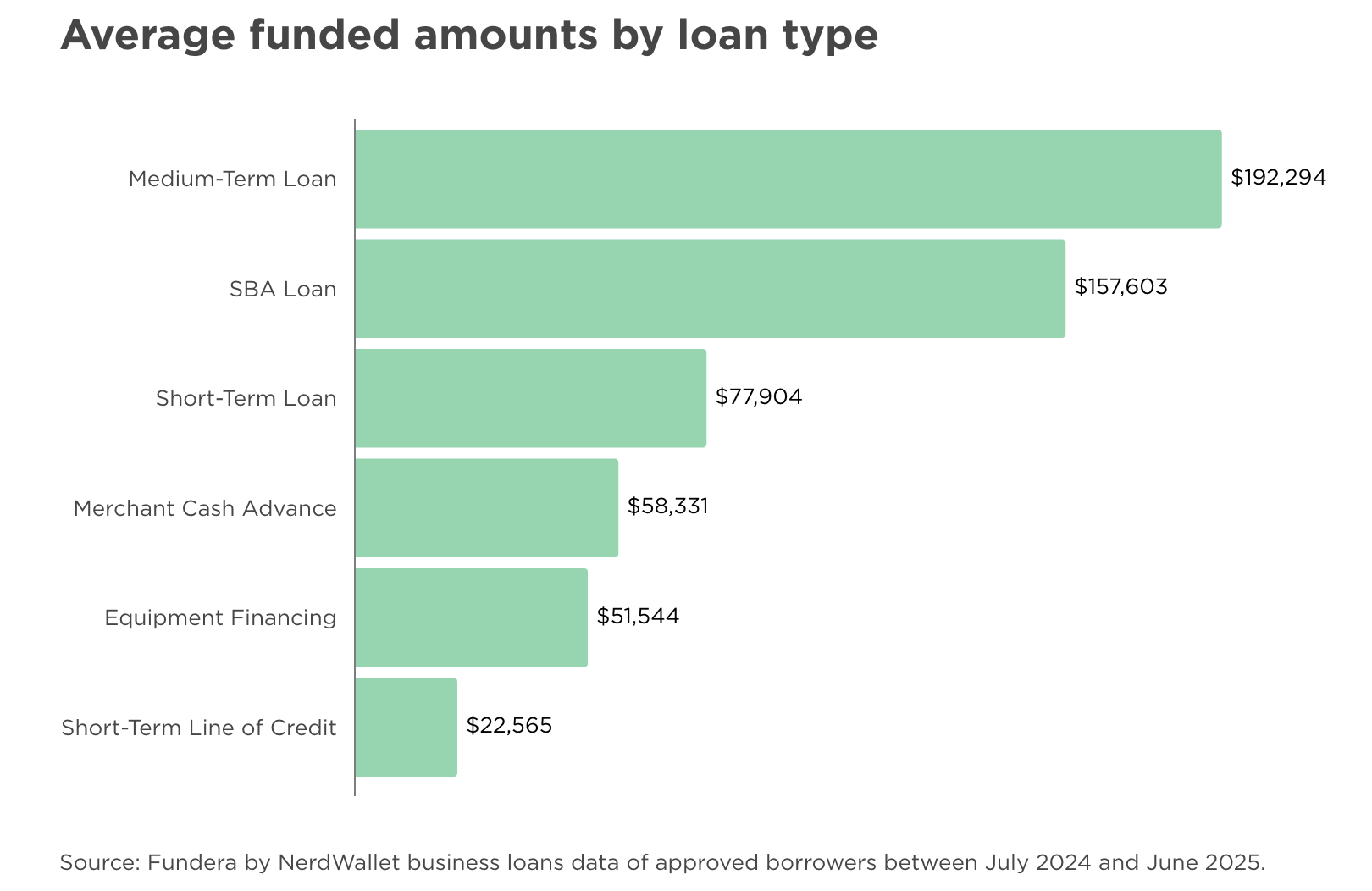

January 26, 2026According to NerdWallet, a leading business loan matching marketplace, the average funded amount of an MCA deal is $58,331. That’s based entirely on the company’s own internal data from July 2024 to June 2025.

Medium-term loans (2-5 years) came in with the highest average of $192,294 and short-term lines of credit produced the lowest average of $22,565.

NerdWallet depends heavily on web traffic to generate leads so this is potentially representative of merchants who use Google or ChatGPT to find financing versus all possible channels.

How a Mother-Daughter Broker Shop Persevered and is Positioned for Growth

January 15, 2026Sharpe Capital facilitated nearly $5 million in funding to small businesses across the United States in 2025. Next year, they hope to double it. What makes the company unique is that it operates as a mother-daughter team, one of the very few in the industry to be structured that way. But how Wendy Rivera and her mother, Sonia Alvelo, got there is a story of circumstances and perseverance.

Alvelo is a known entrepreneur in the space through her own small business finance brokerage Latin Financial, but technically she was also associated with another brokerage at the same time, Sharpe Capital. Her business partner and life partner, Brendan Lynch, co-founded Sharpe with her more than a decade ago, but Lynch primarily ran Sharpe while Alvelo ran Latin, sister companies of sorts but with separate operations. The two celebrated a grand opening of a big joint office in Wethersfield, CT in 2022, which was attended by deBanked and a slate of local politicians. The Sharpe team wore green shirts and the Latin team wore blue.

Sadly, Lynch passed away in December 2024 from cancer at only 45 years old, but not before he could finally tie the knot with Alvelo, making her known as Alvelo-Lynch once and for all. Lynch’s last interview with deBanked happened four months before he passed and one of his final messages he had hoped to get out through us was a reminder for people to remember to take care of their health.

In the challenging time afterward, Alvelo took the reins of Sharpe and eventually her daughter, Wendy Rivera, emerged as a key reason the company continues to be successful.

Rivera, Connecticut-born and raised, had originally been working in retail when she became curious about her mother’s and Lynch’s business in 2018. When working for them became a possible next step for Rivera, they didn’t give in to nepotism and made her interview as a candidate just like anyone else. But she turned it around on them.

“They would tell you that I interviewed them in regards to what the company was and everything like that, but I asked the right questions,” Rivera told deBanked. “Everything was moving smoothly, and I decided to move forward.”

It started off as a part-time gig and eventually became full-time. Her role was to bring in deals and work closely under the tutelage of Lynch, who had a natural knack for connecting with people, particularly small business owners.

“They had a special place for him in their hearts,” Rivera said. “Brendan has taught me so much. He pretty much taught me this industry. I’ve worked with him side by side for the past seven-plus years.”

Rivera obviously learned from her mother as well, but Alvelo’s typical Latin Financial client was primarily from within the Spanish-speaking community while Sharpe’s was much more broad. To give some perspective on that, Alvelo, for example, says that today 80% of her entire Latin Financial customer base resides in Puerto Rico.

So Rivera spent her time on Sharpe and now she’s the primary person responsible for its operations. In what was a transitional year fraught with grief and challenges, the two revamped everything to focus on efficiency. Now they’re finally getting back to thinking about how to expand.

Along the way, Rivera realized that relationships in this business have a tremendous impact and can serve as its own form of marketing.

“Honestly, what’s been working for us is word of mouth,” Rivera said when it comes to acquiring customers. “Really. It sounds very old school but it really works. Once you take care of one merchant, they’ll tell their friends or whoever the case may be, and then they’ll reach out to us, and it just keeps growing that way.”

But those referrals wouldn’t come if they didn’t have the right funders in place to help them out. That means they have to know and trust who they are doing business with on the other side. Coincidentally, attending deBanked events, which Rivera has done, has been an eye-opening experience for her in getting to see who they are working with.

“I feel like once you actually meet the person, I don’t even think a phone call will do enough, you get a feel for what kind of person they are, and if they are in the industry for the right reasons,” Rivera said.

And in all those meetings, another thing she’s realized is that being part of a purely mother-daughter team is unique even within the family business segment of the industry which tends to lean toward father-son. But the two talk business just like any other shop: during work, after work, even during dinner they talk about deals.

Though it’s been a lot and Rivera says she’s overdue for a vacation, she says it’s a job she really enjoys.

“If you love numbers, if you love people, if you love helping people, I think it’s definitely a great position to be in,” Rivera said of working in the industry. “But you have to also be in love with the job as well. Because if you’re not in love with it, there’s going to be a lot of things that’ll hold you back.”

The motivation now is just to pick back up and have an even bigger 2026.

“Brendan and my mom had different ways of running their companies, Sharpe and Latin Financial, and so I feel like [Brendan] kind of taught me his kind of ways for Sharpe Capital and also maybe leaving an open door for opportunities down the road as well,” Rivera said. “And now that I’m in that spot, I can see that.”

Factor Gives Update on “Killing MCAs” in Texas

January 9, 2026Cole Harmonson, CEO of Dare Capital and a board member for the American Factoring Association, posted an update last month on the recent Texas MCA legislation and campaign to “fight the MCA cronies.” It appeared on the Commercial Factor’s magazine website. You can read it here.

Harmonson shared his strategy on how to kill MCAs in Texas, which focuses mainly on the DACA component of securing a first position: “If you get the Springing DACA, then the bank will not give anyone else (i.e., an MCA) a DACA, and therefore no MCA can legally sweep your customer’s account, thereby killing the MCAs in Texas,” he wrote.

Harmonson had previously shared that the factoring industry had been responsible for the MCA legislation in Texas and that it served as a “blueprint,” suggesting that a similar legal framework could be attempted in other states.

Walmart MCA Video Commercial

January 5, 2026Want to see how Walmart is marketing its MCA program?

Check out this commercial:

Walmart became a direct merchant cash advance funder in 2024. You can learn more about it here. Walmart also works with third parties such as Payoneer, Parafin, and Uncapped.

Brokers and Funders – Are You Ready for Changes to California Law Effective January 1, 2026?

December 20, 2025Bob Gage is a partner in Hudson Cook, LLP’s Michigan office. Kate Fisher is a partner in Hudson Cook, LLP’s Maryland office. https://www.hudsoncook.com/

California has a new law, California S.B. 362, impacting how brokers and funders communicate with merchants starting on January 1, 2026. The new law adds provisions to California’s Commercial Financing Disclosures Law (“CFDL”) which became effective in 2023 and established the first law requiring commercial financers and brokers (described in the CFDL as “providers”) to provide cost-of-funding disclosures to applicants. Here is an overview of what you need to know:

Don’t Say “Factor Rate”

Under S.B. 362, commercial financing providers are not allowed to use the term “rate” in a manner that is likely to deceive a recipient. A “recipient” is generally a person who receives an offer of commercial financing of $500,000 or less. The preamble to the new law (which is not part of the law but informs how the regulator will approach enforcement) gives the following example of what California means by likely to deceive:

- Describing the price of credit as “X% fee rate” or “Y% factor rate,” particularly when those “rates” diverge materially from the APR.

A factor rate will almost always be much lower than any APR. This means that California has effectively banned use of the term “factor rate” when communicating with applicants for loans, sales-based financing, merchant cash advance and yes – even factoring transactions. It is probably safe to talk in terms of “factor rates” internally. But, starting on January 1, 2026 – saying “factor rate” to a California recipient can get you into hot water.

Don’t Say “Interest Rate” Unless Referring to an Annual Simple Interest Rate

S.B. 362 also prohibits commercial financing providers from using the term “interest” in a manner that is likely to deceive a recipient. The preamble to the new law gives the following examples of what California means by likely to deceive:

- Describing the price of credit as “simple interest” when referring to a nonannual rate as opposed to a noncompounding annual rate that a reasonable person would understand “simple interest” to mean; and

- Describing the price of credit as an “interest rate” when describing a daily, weekly, or monthly rate and not an annual rate; and

This potentially impacts providers who describe the cost of commercial credit using a daily or weekly rate and describing that rate as “interest”. For example, loan agreements that use a daily, weekly, or monthly “interest rate” may need to be modified.

California Requires Brokers and Funders to Remind Recipients of the Disclosed “APR” or “Estimated APR”

S.B. 362 complicates post-offer negotiations between providers and recipients by requiring redisclosure of the APR or Estimated APR calculation already required by the CFDL. It does this by adding the following new provision to the CFDL:

- After extending a specific offer to a potential recipient, whenever a provider states a charge, pricing metric, or financing amount to the potential recipient for that specific offer during an application process for commercial financing, the provider shall also state the annual percentage rate of that commercial financing offer by using the term “annual percentage rate” or the acronym “APR.”

What this means for providers:

- The APR reminder requirement applies “during an application process.” The term “application process” is not defined, but it probably does not end until the recipient receives funding or the provider definitively declines to proceed with the financing.

- During the “application process,” anytime a provider communicates with the recipient and states a charge, pricing metric, or financing amount, the provider must remind the merchant of the APR or Estimated APR for that offer. Here are examples of how this might impact brokers and funders:

|

New York Already has a Similar Law

New York already has similar requirements in its Commercial Financing Disclosure Law. See 23 N.Y. Admin. Code Section 600.1(f)(1). Accordingly, brokers and funders should implement these practices in New York as well.

This is only a high-level overview and not legal advice. If you have questions regarding how these laws impact your business, please contact knowledgeable counsel.

Bob Gage is a partner in Hudson Cook, LLP’s Michigan office. Kate Fisher is a partner in Hudson Cook, LLP’s Maryland office. https://www.hudsoncook.com/