Sean Murray is the President and Chief Editor of deBanked and the founder of the Broker Fair Conference. Connect with me on LinkedIn or follow me on twitter. You can view all future deBanked events here.

Articles by Sean Murray

Business Finance Brokers in 2025

August 15, 2025

We’re now ten years out from the original “Year of the Broker” article in deBanked Magazine. Brokers are still here, the business has just changed slightly. Here’s some of the top line differences vs. 2015:

Cold Calling: 12% of merchants say they started their search for business funding options from a cold call.

Google Search: Organic search rankings beginning to diminish in favor of AI Q&As.

Training: AI can now listen to every call and grade you on every component of it.

CRMs: Pen and paper are over. Every touch on a deal should be traced and automated and deal tracking organized in a system.

Competition: Every POS solution and merchant fintech software now has a funding button embedded into it.

Commissions: Still high.

Funding Options: Lines of credit, term loans, MCAs, SBA, equipment financing, real estate lending, and more.

Regulations: There are now numerous state registration and disclosure requirements. (See the map here).

Leads: Referral networks are now more valuable than ever. Referrals from CPAs, lawyers, trade associations, chambers of commerce, and more.

Gates: You may have to go through a super broker to get access to a top tier funder.

Startup Costs: The registration requirements in several states has significantly increased the cost of starting a new broker shop today.

Adding Event Connections to DailyFunder

August 12, 2025MY BIG PET PEEVES WITH “EVENT APPS” ARE:

1. 95% of users stop using them after the event is over.

2. Most are white labeled from a third party with no customizable solutions.

3. They are generally zero-sum in that everyone can see you’re going or no one can. People want to choose their own visibility.

4. If a boss buys 10 tickets under their name for their team, it makes it hard for the individual team members to be able to access the app because their info isn’t in the system.

5. There are generally no moderation capabilities to limit or stop abuse.

6. Redundancy.

We had a deBanked Events App (2018 – 2023 white labeled), a deBanked App (2015 – 2017 white labeled), and a DailyFunder App (2013 – 2017 white labeled), but we recently rebooted a DailyFunder App only.

Why DailyFunder? With 17,000+ members, 3 million+ annual page views, and an average session > 10 minutes, it seems the most logical starting point to tackle point 1 above, which is keeping a party going 24/7 instead of just a few days before an event and never again right after. We’ve moved development in-house, no more white labels. We can put events in there whether they’re affiliated with us or not. You can let people know if you’re going or not. You can dm other people that plan to go. You can follow up with them afterwards. You can see the sponsors. We can put video content in there like tech companies that demoed or the interviews on the red carpets. No, you won’t see the whole attendee list, but you’ll be able to see those that want other people to connect with them at each one. You can use your real name or be pseudonymous. We can remove fakers. You can post on the forum. You can see what people are saying. It doesn’t all end when the event ends. You can see news headlines from deBanked and other video content we choose to put on there.

This is a work-in-progress but currently live in the Apple App Store and Google Play Store. If you have ideas or suggestions, email them to webmaster@dailyfunder.com. There’s some bugs we’re aware of. You must have a DailyFunder account already to log in. The registration process is still only on the website but we’ll change that.

Some thoughts are being able to add events like a Title sponsor’s cocktail party, a related golf-outing, etc. People are always asking which company is having a party after an event or before.

So instead of having to go on the forum, facebook groups, linkedin, or the whatsapp chats to be like “yo, xyz is happening.” or “who’s going?” we can just add it in here and then everyone can see them in one place to communicate with each other about them if they want to.

Open to suggestions.

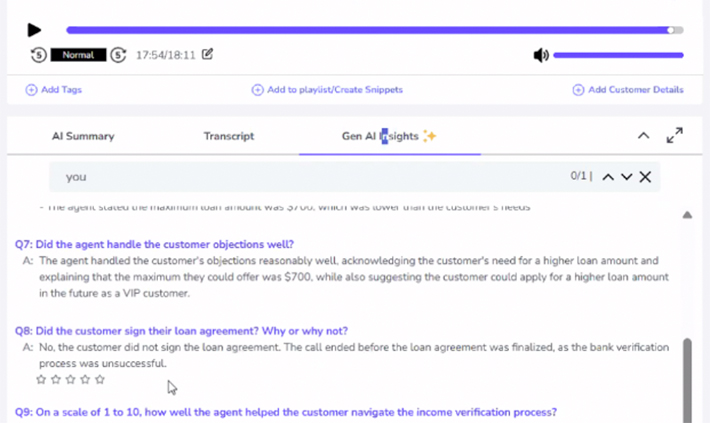

How Are Your Sales Calls Going? How One AI System Can Score Performance

July 21, 2025 The subjectivity era of evaluating sales reps is over. Sales calls can now be dissected down to every little nuance of why something went right or wrong, and it can be done at scale with no human bias. These interactions can also be aggregated to determine strengths, weaknesses, trends, compliance, confidence levels, and more, all thanks to AI and technology available right now.

The subjectivity era of evaluating sales reps is over. Sales calls can now be dissected down to every little nuance of why something went right or wrong, and it can be done at scale with no human bias. These interactions can also be aggregated to determine strengths, weaknesses, trends, compliance, confidence levels, and more, all thanks to AI and technology available right now.

“The way [our] platform works is we integrate with the dialer,” says Atul Grover, Co-founder and VP of Sales for Enthu.AI. “Typically, what we have seen with our clients, the calls are automatically pushed within two or three minutes after the conversations are done.”

With Enthu, a company’s call recordings go through their AI system to be analyzed based on either their own scorecard, the client’s, or both. Whatever the outcome of the call, lost sale, closed deal, or neither, management receives a report to see how the rep performed. Did the rep try to build rapport? What were the objections? Did they handle objections well? Did the rep sound confident when answering difficult questions? Across hundreds or thousands of calls each week, any rep can get an unbiased report card of their strengths and weaknesses. These metrics can then be compared with peers, without the worry of human bias deciding the outcome. They can’t blame the boss for simply favoring another rep, for example.

Originally, when Enthu started, they focused mainly on keyword spotting for compliance purposes, evaluating whether or not reps were saying what they were supposed to across thousands of calls. But that had its limitations.

“That’s how we started our journey, using purely keyword spotting,” Grover says, “but the challenge over there is that you can’t basically expand or scale it. So that’s why we use our AI approach, where it’s primarily intent-based rather than keyword-based. So we look at the intent of all the conversations.”

Rather than AI replacing sales reps, as some theorize might happen over time, it can be used to make them a whole lot better. And this is already being employed today. Enthu, for example, is currently being used in financial services, healthcare, home industries, property management, and more. Grover says clients are already using it to measure disparities in call performance and then using those insights to coach reps who score on the lower end.

“Our platform also offers the ability to create a playlist for the good recordings, which you can use to train your new agents,” Grover says. “So rather than training in general that’s like, ‘okay, this is our company product, this is our company offerings, you should talk like this,’ they can share those good recordings with the new agents so they can listen to how their good sales agents are doing, and then get trained on the real data.”

Recording calls and finding good ones is not a new capability, anyone can do that. But it’s the ability to identify certain call situations at scale that makes all the difference when trying to evaluate and coach. If a new objection is tripping up the team, management can pull every instance it has come up, calculate its frequency, and use that information to determine the best path forward. These are things that would typically rely on the “vibe and feel” of the sales floor, as reps relay information to the boss, who must then assess whether the trend is legitimate or just a statistical blip.

Independent analysis can also be critical when a company is evaluating a lead source or referral partner, especially if that partner is also expecting to be judged objectively. And when the lead source changes, the AI can be told in advance whether the calls are outbound or inbound, hot or cold, or how they differ from other types of calls the company handles. The resulting evaluations can then reflect those circumstances.

Success, in this way, can be gamified, allowing reps to strive for higher grades across all areas of a call and objectively compare themselves to colleagues in an emotion-free environment. The AI can score each call or aspect of a call on a scale from 1 to 10 and produce a summary score for each rep over a day, week, or month, unlocking new motivational challenges. An underperforming rep could be recognized for a top score in overcoming objections, for example, even if they didn’t close the most deals. Picture a Broker Battle, but the judge is an AI.

And it’s not just sales. Clients can also use the technology for compliance, to determine whether proper disclosures were made, correct terminology used, and whether the tone of the call remained positive.

And it’s not just sales. Clients can also use the technology for compliance, to determine whether proper disclosures were made, correct terminology used, and whether the tone of the call remained positive.

“It’s definitely going to be great help for the sales organization,” Grover says. “And if we talk about the lending industry, you talk about compliance and everything, or let’s say the collections department, because they want to make sure that their agents are not screwing up, because there’s legalities involved if they mess up anything. So that’s what our system will flag, where they are doing right or where they’re doing wrong.”

If a client wants to keep keyword spotting as part of the analysis, they can. Grover says pre-set words can be marked as zero-tolerance or flagged for management. The more data and calls the system analyzes, the better it gets.

Grover adds that even if a client isn’t ready to fully integrate Enthu, they can still use old call recordings to access analytics.

“We have some customers in that space where they don’t have a dialer but they still have the recording,” Grover says. “So our platform also allows to upload the recordings directly by the client itself, on the platform itself, where they can upload the calls manually, then you’re still going to get the same intelligence, same analytics, same scorecard mechanism, even if you upload it manually.”

Heron Makes Big Splash in Small Business Finance Industry

July 15, 2025 Heron, a startup using AI to automate workflows, just raised a $16M Series A round. Already a well-known brand in the small business finance industry, the funds will be used to grow their presence, expand into adjacent verticals, and grow their go-to market & and engineering teams.

Heron, a startup using AI to automate workflows, just raised a $16M Series A round. Already a well-known brand in the small business finance industry, the funds will be used to grow their presence, expand into adjacent verticals, and grow their go-to market & and engineering teams.

While Heron serves top tier clientele like insurance carriers and FDIC-insured banks, its technology can be utilized at almost any level.

“Our technology is built to serve funders of all sizes from industry leaders like Bitty, Forward, Vox, and CFG to sub-five person shops originating hundreds of thousands of dollars a month,” the company told deBanked. “If a team is receiving 25 or more submission documents per day, Heron can deliver immediate value by automating their document intake and reducing manual review time. Our platform scales to meet volume, and we often see smaller, fast-moving teams who want to scale submissions and originations without scaling headcount benefit the most from Heron.”

Heron noticed that small business lenders were employing teams of underwriting analysts that spend hours on repetitive intake work and created a process to streamline it within seconds. Consequently, they’ve seen that improving efficiencies in this market has had a positive impact on the economy overall.

“At Heron, we believe that SMB lending is the backbone of the American economy — it powers everything from local restaurants to trucking fleets,” the company said. “But outdated, document-heavy processes slow things down. Heron helps lenders move faster and smarter, so they can get capital to the businesses that need it most.”

Idea Financial Hits Milestone, Will Still Fund in Texas

July 9, 2025

Idea Financial, a nationwide small business lender, recently surpassed $1 billion in funding since inception.

“This is a historic milestone,” said Larry Bassuk, president and co-founder of Idea Financial. “Only a few years ago, this company was just a concept with potential. Like many of the small businesses we serve, we started with confidence, grit, and the unyielding belief that we would succeed. Today, I can proudly announce that Idea Financial’s impact on the small business lending community is significant and positive. This moment belongs to our team, past and present, whose dedication has gotten us here.”

Because the company does term loans and lines of credit, it is not impacted by the recently-passed sales-based financing legislation in Texas and will continue to fund there like normal.

For background, Bassuk and Idea Financial CEO Justin Leto, actually started out in the legal profession as attorneys before taking a risk in small business lending. When deBanked first interviewed the duo in 2019, they said, “We’re not from the finance space, we’re not from the alternative lending space either, we came at this opportunity with a different approach.”

At that time, Idea had only funded $50 million since inception. Much of Idea’s growth since then can be attributed to their broker business, which it is still growing.

“Brokers and referral partners are critical to Idea’s success,” the company said. “While our borrowers are our clients, we also consider brokers and referral partners as clients by our team. We value their business and have made it a focus to develop close, mutually beneficial relationships with them.”

“We have been so fortunate to work with such a talented team, all of whom have contributed to the incredible growth of Idea,” said Leto. “We identified a problem with small business funding when we embarked on this journey, and we are so proud to have played a role in providing the solution that has fueled so many Main Street success stories.”

FundKite, Aquamark Partner on Watermarking Submission Docs

June 17, 2025 As more brokers rush to watermark submission documents to minimize the likelihood of their deals being backdoored, FundKite is codifying the trend into policy by partnering with Aquamark. Aquamark, as readers may recall, was recently spotlighted on deBanked for its defensive watermarking technology which enables brokers to stamp documents in a tamper-resistant manner, marking them as having originated from the broker. If these stamped documents end up in the hands of an unauthorized third party, the watermark reveals their original source. With watermarked submissions on the rise, FundKite will only accept them if they match the originating broker. The company will also encourage brokers to use Aquamark to protect their submissions if they aren’t already doing so.

As more brokers rush to watermark submission documents to minimize the likelihood of their deals being backdoored, FundKite is codifying the trend into policy by partnering with Aquamark. Aquamark, as readers may recall, was recently spotlighted on deBanked for its defensive watermarking technology which enables brokers to stamp documents in a tamper-resistant manner, marking them as having originated from the broker. If these stamped documents end up in the hands of an unauthorized third party, the watermark reveals their original source. With watermarked submissions on the rise, FundKite will only accept them if they match the originating broker. The company will also encourage brokers to use Aquamark to protect their submissions if they aren’t already doing so.

“At FundKite, we take submissions very seriously and want to ensure that the documents we receive have been originated by the ISO submitting them and were not backdoored, which has been a major issue in the industry,” said Alex Shvarts, CEO of FundKite. “We encourage all our ISO partners to watermark their submissions for this reason. Aquamark provides a seamless and inexpensive process we tested and strongly recommend.”

“This partnership reflects a rapidly growing shift in the industry — brokers are fed up with deal theft, and they’re increasingly aware of how critical compliance will be over the next 12 to 24 months,” said Christina Duncan, Founder of Aquamark. “We’re grateful to partner with Alex at FundKite, who’s stepping up to address these challenges by reducing risk, building trust, and helping preserve the integrity of the space as it evolves.”

Texas Passes Law Limiting Sales-Based Financing to 1st Positions Only (and more)

May 29, 2025 The Texas House of Representatives has adopted the Senate’s controversial Commercial Sales-Based Financing amendment that prohibits a sales-based financing provider from automatically debiting any merchant in the state unless they are in a perfected 1st position. With the governor’s signature it will be law. As previously outlined, Texas had introduced its own commercial financing disclosure bill which included many extra requirements such as broker registration, state regulatory oversight, and now… a prohibition on any sales-based financing (with a particular aim at MCAs) where payments are debited that is not a true 1st position with a perfected security interest. It bears mentioning that 1st position here means 1st position out of any other claim altogether, not just other MCAs.

The Texas House of Representatives has adopted the Senate’s controversial Commercial Sales-Based Financing amendment that prohibits a sales-based financing provider from automatically debiting any merchant in the state unless they are in a perfected 1st position. With the governor’s signature it will be law. As previously outlined, Texas had introduced its own commercial financing disclosure bill which included many extra requirements such as broker registration, state regulatory oversight, and now… a prohibition on any sales-based financing (with a particular aim at MCAs) where payments are debited that is not a true 1st position with a perfected security interest. It bears mentioning that 1st position here means 1st position out of any other claim altogether, not just other MCAs.

The passed bill, which is the Senate version on the right hand side of this document, includes the following language:

CERTAIN AUTOMATIC DEBITS PROHIBITED.

A provider or commercial sales-based financing broker may not establish a mechanism for automatically debiting a recipient’s deposit account unless the provider or broker holds a validly perfected security interest in the recipient’s account under Chapter 9, Business & Commerce Code, with a first priority against the claims of all other persons.

While the law specifies sales-based financing, broadly encompassing either a purchase transaction (MCA) or a loan where the payments ebb and flow with sales activity (revenue based finance loan), companies with a special bank relationship are exempt from the law. The exemption applies to: “a bank, out-of-state bank, bank holding company, credit union, federal credit union, out-of-state credit union, or any subsidiary or affiliate of those financial institutions.”

Though the House had until Monday to decide on adopting the Senate’s amendment, the 98 Yeas to the 23 Nays made it a done deal at the very end of yesterday’s legislative session. It now simply awaits the governor’s signature.

Need a Bank to Fund MCAs? You Can’t Operate Without One

May 12, 2025 “I learned back in the early 2000s when merchant processors started to offer merchant cash advances, that was the first time I ever heard of MCA,” said Christian Sanchez, Relationship Manager for the National Deposits Group of Dime Private & Commercial Bank. Sanchez, who’s been in banking for 25 years, understands MCAs in their current iteration from a unique vantage point in the ecosystem. Dime, for example, is a full‑service commercial bank based in New York that today provides a variety of customers, including MCA funding companies, with services like checking accounts, wire access, and ACHs.

“I learned back in the early 2000s when merchant processors started to offer merchant cash advances, that was the first time I ever heard of MCA,” said Christian Sanchez, Relationship Manager for the National Deposits Group of Dime Private & Commercial Bank. Sanchez, who’s been in banking for 25 years, understands MCAs in their current iteration from a unique vantage point in the ecosystem. Dime, for example, is a full‑service commercial bank based in New York that today provides a variety of customers, including MCA funding companies, with services like checking accounts, wire access, and ACHs.

Sanchez worked with his first MCA client in 2021 and immersed himself in their business and the industry. When he got them onboarded and saw how well it worked out, he knew there was something there. By early 2024, he set out to find a place where he could meet many MCA funders at once and attended the deBanked CONNECT MIAMI conference that January. It was almost right afterward that he started a new role at Dime, and he has been actively looking to serve MCA companies ever since.

“Through the connections I made—I attended Broker Fair in New York last May and from there my access to the industry has been great and I continue to meet contacts, and one contact leads me to another,” Sanchez said.

It’s more than just a basic account that Dime is offering to MCA funders.

“Our platform is designed to give you the tools that you need to run your MCA funding company,” he said, “coming in from the standard online banking access, being able to view your accounts, run reports, extract information to your accounting system… We give you access to our ACH platform, which allows you to set up your payment collections, and based on how your deal is structured with the merchant, you can set those up with the different recurring schedules.”

Dime customers can also continue to use their own third‑party ACH processor if they choose.

Banking, believe it or not, can be one of the most overlooked considerations in running a funding company. A bank’s underwriting team has to understand the business, be comfortable with it, approve it, and be prepared to handle the flurry of activity—yet, even when they do, things may not always run smoothly. To that end, Sanchez said that even if someone already has an MCA banking relationship elsewhere and doesn’t want to switch to Dime, being fully onboarded with another bank as a backup is a smart plan. The time‑sensitivity surrounding things like wire deadlines and daily ACHs is critically important in the industry. It’s crucial not to wait until it’s too late for that Plan B, since onboarding and risk underwriting are neither instantaneous nor guaranteed.

“Obviously I would love to be the primary and having the biggest share,” Sanchez said. “But at the end of the day, it’s business. If I can be part of your business and work together, then I fulfill my need.”

Credit facilities, investors, and syndicates may also require an MCA funder to have a backup bank ready to go as a condition of working together. They might even require a Deposit Account Control Agreement (DACA), which Dime is equipped to put in place.

“[A DACA] is a tri‑party agreement between the MCA funder, the lender, and the bank,” Sanchez explained. “And what happens is this is a way for a lender to ensure that the MCA is doing what they say they were going to do…”

Dime customers need not be located in New York, but those who want to drop in on their banker can do so at the Midtown Manhattan branch or set up a meeting with Sanchez himself.

Dime customers need not be located in New York, but those who want to drop in on their banker can do so at the Midtown Manhattan branch or set up a meeting with Sanchez himself.

“A lot of times what I can assure you is, if you look for me, you can find me, whether it’s by phone or we might be meeting somewhere but I’m constantly available.”

True to that promise, Sanchez said he will once again attend Broker Fair in person on May 19 in New York City.

It’s important to note that, as a bank, there is still a rigorous underwriting process and not every company may be approved.

“It’s absolutely amazing to see how Dime is willing to work with MCAs,” he said. “We have a clear understanding of the industry, the risk that’s involved with it, but the bank has embraced it instead of running away.”