Articles by Ed McKinley

Consultative Selling in Small Business Finance

October 16, 2019

It’s nearly impossible to teach fiscal responsibility to most consumers, according to researchers at universities and nonprofit agencies. But alternative small-business funders and brokers often manage to steer clients toward financial prudence, and imparting pecuniary knowledge can become part of a consultative approach to selling.

It’s nearly impossible to teach fiscal responsibility to most consumers, according to researchers at universities and nonprofit agencies. But alternative small-business funders and brokers often manage to steer clients toward financial prudence, and imparting pecuniary knowledge can become part of a consultative approach to selling.

Still, nobody says it’s easy to convince the public or merchants to handle cash, credit and debt wisely and responsibly. Consider the consumer research cited by Mariel Beasley, principal at the Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University and co-director of the Common Cents Lab, which works to improve the financial behavior of low- and moderate-income households.

“For the last 30 years in the U.S. there has been a huge emphasis on increasing financial education, financial literacy,” Beasley says. But it hasn’t really worked. “Content-based financial education classes only accounted for .1 percent variation in financial behavior,” she continues. “We like to joke that it’s not zero but it’s very, very close.” And that’s the average. Online and classroom financial education influences lower-income people even less.

The problem stems from trying to teach financial responsibility too late in life, says Noah Grayson, president and founder of Norwalk, Conn.-based South End Capital. He advocates introducing young people to finance at the same time they’re learning history, algebra and other standard subjects in school.

Yet Grayson and others contend that it’s never too late for motivated entrepreneurs to pick up the basics. Even novice small-business owners tend to possess a little more financial acumen than the average person, they say. That makes entrepreneurs easier to teach than the general public but still in need of coaching in the basics of handling money.

Take the example of a shopkeeper who grabs an offer of $50,000 with no idea how he’ll use the funds to grow the business or how he’ll pay the money back, suggests Cheryl Tibbs, general manager of One Stop Commercial Capital, Douglasville, Ga. “The easy access to credit blinds a lot of merchants,” she notes.

Entrepreneurs often make bad decisions simply because they don’t have a background in business, according to Jared Weitz, CEO of New York based United Capital Source. “Many of the people who come to us are trying their hardest,” he observes.

Entrepreneurs often make bad decisions simply because they don’t have a background in business, according to Jared Weitz, CEO of New York based United Capital Source. “Many of the people who come to us are trying their hardest,” he observes.

Weitz offers the example of his own close relative who’s a veterinarian. That profession attracts some of the brainiest high-school valedictorians but doesn’t mean they know business. “He’s the best doctor ever and he’s not a great businessman because he doesn’t think about those things first. What he thinks about is helping people. That’s why he got into his profession.”

Entrepreneurs often devote themselves to a vision that isn’t businesses-oriented. “They start a business because they have a great idea or a great product, and that’s what excites them,” Grayson says. “They jump in with both feet and don’t think much about the business side.” The business side isn’t as much fun.

Merchants also attend to so many aspects of an enterprise—everything from sales, production and distribution to hiring, payroll and training—that they can’t afford to devote too much time to any single facet, notes Joe Fiorella, principal at Kansas City, Mo.-based Central Funding. Business owners respond to what’s most urgent, not necessarily what’s most important.

For whatever reason, some business owners spiral downward into financial ruin, bouncing checks, stacking merchant cash advances and continually seeking yet another merchant cash advance to bail them out of a precarious situation, says Jeremy Brown, chairman of Bethesda, Md.-based Rapid Advance.

Weitz advises sitting down with those clients and coming to an understanding of the situation. In some cases, enough cash might be coming in but the incoming autopayments aren’t timed to cover the outgoing autopayments, he says by way of example.

Informing clients of such problems makes a demonstrable difference. “We can see that it works because we have clients renewing with us,” says Weitz. “We’re able to swim them upstream to different products” as their finances gradually improve, he says.

The products in that stream begin with relatively higher-cost vehicles like merchant cash advances and proceed to other less-expensive instruments with better terms, says Brown. Those include term loans, Small Business Administration loans, equipment leasing, receivables factoring and, ultimately the goal for any well-capitalized small business—a relationship with the local bank.

Failing to consider those options and instead simply abetting stackers to make a quick buck can give the industry a “black eye,” and it benefits none of the parties involved, Tibbs observes. But merchants deserve as much blame as funders and brokers, she maintains.

Prospective clients who stack MCAs, don’t care about their credit rating and simply want to staunch their financial bleeding probably account for 35 percent to 40 percent of the applicants Tibbs encounters, she says.

Just the same, alt-funders continue to urge clients to hire accountants, consult attorneys, employ helpful software, shore up credit ratings, keep tabs on cash flow, calculate margins, improve distribution chains and outline plans for growth. It’s what helps the industry rise above the “get-money quick” image that it’s outgrowing, Weitz, says. Many funders and brokers consider providing financial advice an essential aspect of consultative selling. It’s an approach that begins with making sure applicants understand the debt they’re taking on, the terms of the payback and how their businesses will benefit from the influx of capital. It continues with a commitment to helping clients not just with funding but also with other types of business consultation.

“It’s not so much selling as building a rapport with clients—serving as a strategic advisor or financial resource for them, identifying their needs and directing them to the right loan product to meet those needs,” says Grayson. “They should feel they can call you about anything specific to their business, not just their loan requests.” He also cautions against providing information the client will not absorb or will find offensive.

Justin Bakes, CEO of Boston-based Forward Financing also advocates consultative selling. “It’s all about questions and getting information on what’s driving the business owner,” he says. “It’s a process.”

Consultative sales hinges on knowing the customer, agrees Jason Solomon, Forward Financing vice president of sales. “Businesses are never similar in the mind of the business owner,” he notes. “To effectively structure a program best-suited to the merchant’s long-time business needs and set a proper path forward to better and better financial products, you need to know who the business owner is and what his long term goals are.”

“It’s taking an approach of actually being a consultant as opposed to a $7 an hour order taker,” Tibbs says of consultative selling. “I like to teach new reps to think of it as if you were a doctor. Doctors ask questions to arrive at a final diagnosis. So if you’re asking your prospective customer questions about their business, about their cash flow, about their intentions of how they’re planning to get back on track.”

Learning about the clients’ business helps brokers recommend the least-expensive funding instrument, Tibbs says. “I really hate to see someone with a 700 credit score come in to get a merchant cash advance,” she maintains. The consultative approach requires knowing the funding products, knowing how to listen to the customer and combining those two elements to make an informed decision on which product to recommend, she notes.

Consultative sales can greatly benefit clients, Weitz maintains. If a pizzeria proprietor asks for an expensive $50,000 cash advance to buy a new oven, a responsible broker may find the applicant qualifies for an equipment loan with single-digit interest and monthly payments over a five-year period that puts less pressure on daily cash flow.

Consultative sales can greatly benefit clients, Weitz maintains. If a pizzeria proprietor asks for an expensive $50,000 cash advance to buy a new oven, a responsible broker may find the applicant qualifies for an equipment loan with single-digit interest and monthly payments over a five-year period that puts less pressure on daily cash flow.

It’s also about pointing out errors. Brokers and funders see common mistakes when they look at tax returns and financial records, says Brown. “The biggest issue is that small-business owners—because they work so hard— make a profit of X amount of money and then take that out of the business,” he notes. Instead, he advises reinvesting a portion of those funds so that they can build equity in the business and avoid the need to seek outside capital at high rates.

Another common error occurs when entrepreneurs take a short-term approach to their businesses instead of making longer-term plans, Brown says. That longer-term vision includes learning what it takes to improve their businesses enough to qualify for lower-cost financing.

Sometimes, small merchants also make the mistake of blending their personal finances and their business dealings. Some do it out of necessity because they’re launching an enterprise on their personal credit cards, and others act of ignorance. “They don’t necessarily know they’re doing something wrong,” Grayson observes. “There are tax ramifications.”

Some just don’t look at their businesses objectively. Take the example of a company that approached Central Funding for capital to buy inventory in Asia. Fiorella studied the numbers and then informed the merchant that it wasn’t a money problem—it was a margins problem. “You could sell three times what you’re wanting to buy, and you still won’t get to where you want to be,” he reports telling the potential customer.

Consultative selling also means establishing a long-term relationship. Forward Financing uses technology to keep in contact with clients regularly, not just when clients need capital, Bakes notes. That cultivates long-lasting relationships and shows the company cares. As the relationship matures it becomes easier to maintain because the customers want to talk to the company. “They’re running to pick up the phone.”

The conversations that don’t hinge on funding usually center on Forward Financing learning more about the customer’s business, says Solomon. That include the client’s needs and how they’ve used the capital they’ve received.

“We have our own internal cadence and guidelines for when we reach out and how often and what happens,” says Solomon. Customer relationship management technology provides triggers when it’s time for the sales team or the account-servicing team to contact clients by phone or email.

Do small-business owners take advice on their finances? Some need a steady infusion of capital at increasingly higher cost and simply won’t heed the best tips, says Solomon. “It’s certainly a mix,” he says. “Not everybody is going to listen.”

Paradoxically, the business owners most open to advice already have the best-run companies, says Fiorella. Those who are closed to counseling often need it the most, he declares.

Moreover, not everybody is taking the consultative approach. “New brokers are so excited to get a commission check they throw the consultative approach out the window,” Tibbs says.

Yet many alt-funders bring consultative experience from other professions into their work with providing funds to small business. Tibbs, for example, previously helped home buyers find the best mortgage.

Consultative selling came naturally to Central Funding because the company started as a business and analytics consultancy called Blue Sea Services and then transformed itself into an alternative funding firm, says Fiorella. Central Funding reviews clients’ financial statements and operations between rounds of funding, he notes.

Consultations with borrowers reach an especially deep level at PledgeCap, a Long Island-based asset-based lender, because clients who default have to forfeit the valuables they put up as collateral—anything from a yacht to a bulldozer—says Gene Ayzenberg, PledgeCap’s chief operating officer. Conversations cover the value of the assets and the risk of losing them as well as the reasons for seeking capital, he notes.

No matter how salespeople arrive at their belief in the consultative approach, they last much longer in the business than their competitors who are merely seeking a quick payoff, Tibbs says. Others contend that it’s clearly the best way to operate these days.

“The consultative approach is the only one that works,” says Weitz. “Today, everything is about the customer experience. People are making more-educated, better informed decisions.” What’s more, with the consultative approach clients just keep getting smarter, he adds.

The days of the hard sell have ended, Grayson agrees. Customers have access to information on the internet, and brokers and funders can prosper by helping customers, he says. “Our compensation doesn’t vary much depending upon which product we put a client in so we can dig deeper into what will fit the client without thinking about what the economic benefit will be to us.”

Even though the public has become familiar with alternative financing in general, most haven’t learned the nuances. That’s where consultative selling can help by outlining the differing products now available for businesses with nearly any type of credit-worthiness. “It’s for everybody,” Weitz says of today’s alternative small business funding, “not just a bank turn-down.”

Born To Borrow

August 26, 2019 Consumer debt has surpassed $4 trillion for the first time, and it’s continuing its ascent into the stratosphere. It’s getting big enough to trigger the next recession, and financial education isn’t changing the underlying consumer behavior.

Consumer debt has surpassed $4 trillion for the first time, and it’s continuing its ascent into the stratosphere. It’s getting big enough to trigger the next recession, and financial education isn’t changing the underlying consumer behavior.

Personal loan balances shot up $21 billion last year to close 2018 at a record high of $138 billion, according to a TransUnion Industry Insights Report. The average unsecured personal loan debt per borrower was $8,402 as of the end of last year, TransUnion says.

Much of the increase in consumer debt has emerged with the rise of fintechs— such as Personal Capital, Lending Club, Kabbage and Wealthfront—notes Rutger van Faassen, vice president of consumer lending at a U.S. office of London-based Informa Financial Intelligence, a company that advises financial institutions and operates offices in 43 countries.

In fact, Fintech loans now comprise 38% of all unsecured personal loan balances, a larger market share than any of the more traditional institutions, the TransUnion report notes. Banks’ market share has decreased from 40% in 2013 to 28% today, while credit unions’ share has declined from 31% to 21% during the same time period, TransUnion says.

Fintechs are also gaining at the expense of the home- equity market, van Faassen maintains. “They’re eating away at some of the balance that maybe historically was in home-equity loans,” he says. While total debt is increasing, the amount that’s in home equity loans is actually shrinking, he notes.

Fintechs are also gaining at the expense of the home- equity market, van Faassen maintains. “They’re eating away at some of the balance that maybe historically was in home-equity loans,” he says. While total debt is increasing, the amount that’s in home equity loans is actually shrinking, he notes.

What’s more, fintechs are changing the way Americans think about credit, van Faassen continues. Until recently, consumers experienced a two step process. First, they identified a need or desire, like a washer and dryer or home renovation. Realizing they didn’t have the cash to fund those dreams, they took the second step by approaching a financial institution for a loan.

If consumers chose a home equity line of credit to procure the cash, they had to wait for something like 40 days from the beginning of the application process to the time they got the money, van Faassen says. “You really had to be sure you wanted something,” or the process wasn’t worth the effort, he says.

Fintechs have removed a lot of the “pain” from that process, van Faassen says. With algorithms helping to assess the risk that an applicant can’t or won’t repay a debt and digitization easing access to financial records, fintechs can quickly evaluate and make a decision on an application. Tech also helps assess applicants with thin or nonexistent credit files, which broadens the clientele while also contributing to total consumer debt.

Meanwhile, mimicking an age old process in the car business, merchants are beginning to make credit available at the point of sale. Walmart, for example, recently signed a deal with Affirm, a Silicon Valley lender, to provide point-of-sale loans of three, six or 12 months to finance purchases ranging from $150 to $2,000. Shoppers apply for the loans by providing basic information on their mobile phones and don’t have to talk to anyone in person about their finances. Affirm’s CEO Max Levchin has called the underwriting process ‘basically instant.”

If that convenience comes at too high a cost, it doesn’t matter much because borrowers can later find another finance vehicle with better terms, van Faassen says. “So if I get the money at the point of sale, which might have been zero for six months and then it steps up to 20-plus percent, there is no problem with refinancing that debt,” he says.

But there’s a downside to the ease of borrowing, van Faassen cautions. It could trigger the next recession, even though unemployment remains low. Despite modest recent gains, wages have remained nearly stagnant for years. That means an increase in interest rates could lessen consumers’ ability to pay off their debts, he says.

Meanwhile, at least some large mortgage lenders have begun running into problems, a situation that bears an eerie resemblance to the beginning of the Great Recession that struck near the end of 2007, notes a report in luckbox magazine, a publication for investors. Stearns Holding, the parent of Sterns Lending, the nation’s 20th largest mortgage lender, filed for bankruptcy protection just after the July 4 holiday, the luckbox article says.

Meanwhile, at least some large mortgage lenders have begun running into problems, a situation that bears an eerie resemblance to the beginning of the Great Recession that struck near the end of 2007, notes a report in luckbox magazine, a publication for investors. Stearns Holding, the parent of Sterns Lending, the nation’s 20th largest mortgage lender, filed for bankruptcy protection just after the July 4 holiday, the luckbox article says.

Another worrisome sign with regard to the possibility of recession is emerging as institutional investors buy into the peer to peer lending market. Institutional investors bought batches of sliced and diced home mortgage securities that helped bring about the Great Depression.

Then there’s the nagging notion that the country and the world are becoming ripe for recession simply because no downturns have occurred for a while. Talk to that effect was circulating at the recent LendIt Conference, van Faassen observes. Fintech executives often come from the banking world and thus still find themselves haunted by the specter of the Great Recession. That’s why they’re already beginning to tighten underwriting for consumer credit van Faassen says.

One difference this time around lies in the fact that nothing about the increase in consumer debt appears to be hidden from public view, van Faassen says. Before, investors fell victim to the mistaken impression that risky mortgage-backed securities were rated AAA when they weren’t.

Plus, the increase in peer-to-peer lending could keep the economy going even if big financial institutions freeze the way they did during the Great Recession, van Faassen notes. “Hopefully, with the new structures that are out there, we can keep liquidity going,” he says. That raises key questions for the alternative small- business funding community. The industry came into being partly as a response to banks’ tightened lending policies during the Great Recession, so perhaps a downturn isn’t such a bad thing for the sector. But a downturn for the economy in general could cripple merchants’ ability to pay off debt.

But all bets are off during hard times. In the last recession the conventional wisdom that consumers make their mortgage payment before paying other bills was turned on its head. Instead of making the house payment—because foreclosure would take several months—people were choosing to make their car payments so they could get to work. Nobody really knows ahead of time what will happen in a recession, van Faassen notes.

After all, economics relies to at least some degree upon the often-irrational financial decisions of the general public. And science demonstrates that it’s no easy task to convince consumers to handle their cash, credit and debt responsibly, says Mariel Beasley, principal at the Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University and Co-Director of the Common Cents Lab (CCL), which works to improve the financial behavior of low- to moderate-income households.

“For the last 30 years in the U.S. there has been a huge emphasis on increasing financial education, financial literacy,” says Beasley. But it hasn’t really worked. “Content-based financial education classes only accounted for .1 percent variation in financial behavior,” she continues. “We like to joke that it’s not zero but it’s very, very close.” And that’s the average. Online and classroom financial education influenced lower-income people even less.

Lots of other factors influence financial behavior, Beasley notes. How much a person saves, for example, depends upon how much they make, what their bank tells them and what practices they encountered at home as children, she says. The CCL has been finding out some other things, too.

Lots of other factors influence financial behavior, Beasley notes. How much a person saves, for example, depends upon how much they make, what their bank tells them and what practices they encountered at home as children, she says. The CCL has been finding out some other things, too.

In one example of its findings, it discovered that putting an amount for a minimum payment on a credit card decreases how much consumers pay. That happens because listing a minimum payment amount creates an anchor, and borrowers adjust their payment upward from there, Beasley says. If the card carrier doesn’t specify a minimum, consumers tend to adjust downward from the full amount they owe. “It turns out to be incredibly powerful,” she contends.

It’s the kind of problem that shows financial institutions haven’t devised many systems to reduce consumer debt by speeding up repayment, Beasley maintains. In this example, suggesting higher payments would prompt some consumers to pay off their debt more quickly.

In an exception to standard practice, a credit card company called Petal does exactly that by placing a slider on its website to help borrowers determine the amount of their payment, she notes.

Meanwhile, people tend to base financial decisions on the examples they see other people set, Beasley says. Problems arise with that tendency because they may see one neighbor spending money freely to dine in restaurants but don’t see any of the many neighbors eating at home to save money. They see a neighbor driving a new car but don’t know how much that neighbor is setting aside for retirement.

That’s why most people overestimate how much others spend to dine out in restaurants, Beasley says. When shown the error, most reduce their own spending in restaurants, she notes, but within two weeks their behavior returns to its original level, their newfound knowledge “drowned out by the noise in the world,” she says.

That’s not good for consumers or small businesses, but help is on the way, according to John Thompson, chief program officer of the Financial Health Network, a national nonprofit research and consulting firm that works with financial institutions and other companies to improve consumer financial health.

As part of that mission, the Network has formulated procedures to assess the financial health of individuals and small businesses, Thompson says. It’s too early to say whether the tool will help with loan underwriting, he notes, but financial wellness determines the ability to pay back debt, he notes.

The Network also publishes the U.S. Financial Health Pulse, which recently pronounced just 28% of Americans financially healthy, meaning that they have sufficient income, savings and planning to handle an unexpected expense and act on the decisions they make. About 55% are relegated to various stages of coping, and 17% find themselves in a vulnerable state.

So Americans aren’t feeling financially secure, and they’ve borrowed $4 trillion to reach that unenviable state. They’re borrowing more and learning virtually nothing useful about their financial errors. Thompson has a way of summing up the situation. “It’s crazy,” he says.

So God Made a Farmer, But Who’s Financing The Farms?

May 1, 2019 Most mornings, farmers and ranchers wake up worrying about uncooperative weather and volatile commodity prices. Just the same, they pull themselves out of bed to spend the morning tinkering with crotchety machinery or wrangling uncooperative livestock. When they break for lunch, the kitchen radio alerts them to trade wars with distant countries and the unintended results of federal regulation. As they make their way back outdoors for the afternoon’s work, they can’t help but notice another new house taking shape in the distance as suburban sprawl encroaches on the fields and pastures. By evening, their thoughts have turned to their need for short-term capital and how the local banker seems increasingly wary of providing funds.

Most mornings, farmers and ranchers wake up worrying about uncooperative weather and volatile commodity prices. Just the same, they pull themselves out of bed to spend the morning tinkering with crotchety machinery or wrangling uncooperative livestock. When they break for lunch, the kitchen radio alerts them to trade wars with distant countries and the unintended results of federal regulation. As they make their way back outdoors for the afternoon’s work, they can’t help but notice another new house taking shape in the distance as suburban sprawl encroaches on the fields and pastures. By evening, their thoughts have turned to their need for short-term capital and how the local banker seems increasingly wary of providing funds.

It’s that last challenge where the alternative small-business funding industry might be able to help, says Peter Martin, a principal at K-Coe Isom, an accounting and consulting firm focused on the ag industry. “If you as a farmer need operating funds and you can’t get them from a bank, you don’t have a lot of options,” he says. “Historically, nobody outside of banks has had much interest in lending operating money to a farmer.”

The result of that reluctance to provide funding? “I can’t tell you the number of calls I get to say, ‘Hey, I need $100,000 and I need it in a couple of days because of X, Y, Z that’s come up,’” says Martin. “We don’t have a place that we can send those people to. You could make a lot of quick turnaround loans in rural America.” What’s more, it’s a potential clientele that makes a lot of money and prides itself on paying back what they owe.

Martin’s not alone in that assessment. While farmers enjoy abundant long-term credit to buy big-ticket assets, such as land and heavy machinery, they’re struggling to find sources of short-term credit for operating expenses like labor, repairs, fuel, seed, feed, fertilizer, herbicides and pesticides, notes Mike Gunderson, Purdue University professor of agricultural economics.

But remember that nobody’s saying it would be easy for alt funders to break into the agricultural sector. City folks accustomed to the fast-paced rhythms of New York or San Diego would have to learn a whole new seasonal business cycle. Grain farmers, for example, plant corn and soybeans in April, harvest their crops September or October, and may not sell the grain until the following January, says Nick Stokes, managing director of Conterra Asset Management, an alternative-funding company that places and services rural real estate loans.

But remember that nobody’s saying it would be easy for alt funders to break into the agricultural sector. City folks accustomed to the fast-paced rhythms of New York or San Diego would have to learn a whole new seasonal business cycle. Grain farmers, for example, plant corn and soybeans in April, harvest their crops September or October, and may not sell the grain until the following January, says Nick Stokes, managing director of Conterra Asset Management, an alternative-funding company that places and services rural real estate loans.

That seasonality results in revenue droughts punctuated by floods of revenue – a circumstance far-removed from the more-consistent credit card receipt split that launched the alternative small-business funding industry. Alternative funders seeking customers with consistent monthly cash flow won’t find them in the agricultural sector, Stokes cautions.

And while the unfamiliarity of farm life might begin with wild swings in cash flow, it doesn’t end there. Operating in the agricultural sector would require urbanites to learn the somewhat alien culture of The Heartland – a way of life based on hard physical labor, the fickle whims of the weather, and friendly unhurried conversations, even with strangers.

Even so, the task of mastering the agricultural funding market isn’t hopeless, and help’s available. Experts in agricultural economics profess a willingness to help outsiders learn what they need to know to get involved. “Selfishly, the first place I’d love to have them reach out to is me,” Martin says of alternative funders. “I’ve been writing and thinking for years about the importance of getting some non-traditional lenders into agriculture.” He would have “no qualms” about featuring specific prospective funders in a column he writes for one of the nation’s largest farm publications.

It also requires meet-and-greets. During the winter, when farmers aren’t in the fields, funders could make connections at trade shows, Martin advises. “Word would get around rural America really quick,” he predicts. Networking with advisers such as crop insurance agents, agronomists and ag CPS’s – all of whom deal with farmers daily – would also help funders find their way in agriculture, he contends.

It also requires meet-and-greets. During the winter, when farmers aren’t in the fields, funders could make connections at trade shows, Martin advises. “Word would get around rural America really quick,” he predicts. Networking with advisers such as crop insurance agents, agronomists and ag CPS’s – all of whom deal with farmers daily – would also help funders find their way in agriculture, he contends.

Investors who are curious about extending credit in the agricultural sector could rely upon Conterra to help them locate customers and help them service the loans, says Stokes. He can even help acclimate them to the world of agriculture. “If they’re interested in investing in agricultural assets – whether that be equipment, real estate or providing operating capital – we would enjoy the opportunity to visit with them,” he says.

GETTING STARTED

Alt funders could begin their introduction to the agrarian lifestyle by taking to heart a quotation attributed to President John F. Kennedy: “The farmer is the only man in our economy who buys everything at retail, sells everything at wholesale and pays the freight both ways.”

“Agriculture is a very different animal,” Martin notes. He sometimes presents a slide show to compare the difference between a typical farm and a typical manufacturer of the same size. At the factory, revenue ratchets up a bit each year and margins remain about the same over time. On the farm, revenue and margins both fluctuate wildly in huge peaks and valleys from one year to the next.

The volatility makes it difficult to manage the risk of lending, Martin admits, while noting that agriculturally oriented banks still have higher returns than non-ag banks, according to FDIC records. “You have to go back to 2006 to find a time when ag banks didn’t outperform their peers on return on assets,” he says. “What this tells us is that, generally speaking, ag borrowers are better at repaying their loans,” he asserts. Charge-offs and delinquencies in ag portfolios are lower than in other industries, he says.

Many of the nation’s farms have remained in the same family for more than a century – a stretch of time that’s seldom seen in just about any other type of business. Besides making potential creditors comfortable that a particular operation will stay in business, the longevity of farms provides lots of documents to examine – not just tax records but also production history that’s tracked by government agencies. A particular farmer’s crop yields, for example, can be compared with county averages to calculate how good the borrower is at farming.

Debt to asset ratio on the nation’s farms stands at about 14 percent, which Martin views as “insanely low.” But that’s not the case on every farm. Highly leveraged farms have ratios of 60 percent or even 80 percent when farmers have grown their businesses quickly or encountered debt to buy land from their parents, he says. Commodity prices are low now, but farms with 14 percent debt to asset ratios still don’t have a problem, even in hard times. Farmers deeply in debt, however, have little ability to climb out of the hole. The latter are using operating capital to fund losses.

Farmers with debt to asset ratios of 10 percent have little trouble finding credit and aren’t going to pay anything other than bank rates, Martin says. The target audience for non-traditional funding are farmers who are having trouble but will be fine when commodity prices rebound. Another potential client for alternative finance would be farmers who are quickly increasing the size of their operations when opportunities arise to acquire land. Both groups need funders willing to contemplate the future instead of demanding a perfect track record, he maintains.

Farmers with debt to asset ratios of 10 percent have little trouble finding credit and aren’t going to pay anything other than bank rates, Martin says. The target audience for non-traditional funding are farmers who are having trouble but will be fine when commodity prices rebound. Another potential client for alternative finance would be farmers who are quickly increasing the size of their operations when opportunities arise to acquire land. Both groups need funders willing to contemplate the future instead of demanding a perfect track record, he maintains.

Farmers generally need loans for operating capital for about 18 months, according to Martin. “Let’s say I borrow that money, get my crop in the ground, harvest that and I may not sell my grain right after harvest,” he says. The whole cycle can easily take 18 months, he says. Shorter-term bridge lending opportunities also arise in situations like needing a little extra cash quickly at harvest time. Farmers usually have something to put up as collateral – like producing 50 titles to vehicles or offering up some real estate, he says.

An unsecured loan – even one with high double-digit interest – could succeed in agriculture because no one is offering that type of funding, Martin says. Small and medium-sized farms would probably benefit from funding of $100,000 or less, while larger farms might sign up for that amount but often require more, he notes.

LAY OF THE LAND

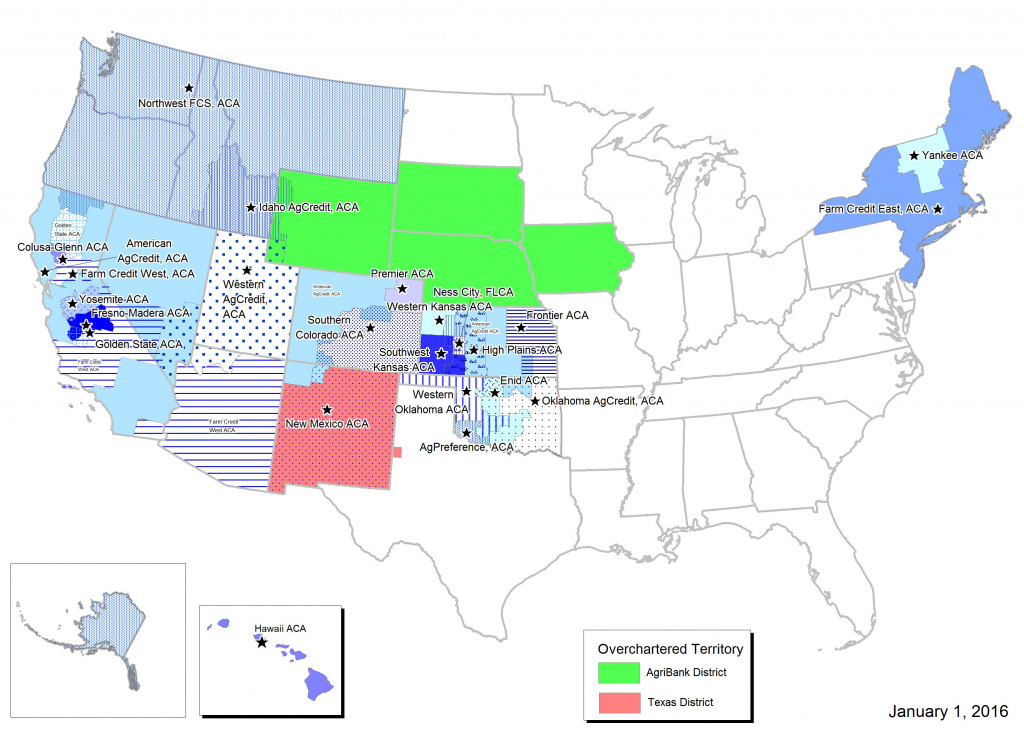

The Farm Credit System, a nationwide quasi-governmental network of borrower-owned lending institutions, provides more than a third of the credit granted in rural America. That comes to more than $304 billion annually in loans, leases and related services to farmers, ranchers, rural homeowners, aquatic producers, timber harvesters, agribusinesses, and agricultural and rural utility cooperatives, according to published reports.

Congress established the Farm Credit System in 1916, and the Farm Credit Administration was established in 1933 to provide regulatory oversight. “All they’re doing is lending money to agriculture,” says Martin.

However, the system can go astray in the eyes of some observers. An arm of the Farm Credit System called CoBank lends to co-operatives and other rural entities. At one point Verizon Wireless became a borrower from CoBank, which angered some observers because the system was supposed to be helping rural America, not corporate America, Martin says.

That anger arises partly because the federal government doesn’t require Farm Credit to pay income tax, which enables it to lend at lower rates, Martin says. “Part of the allure of borrowing from Farm Credit is you can typically borrow cheaper,” he notes. “You’d be very hard pressed to find a farmer who over the years hasn’t had some interaction with Farm Credit.”

Observers sometimes fault the system for what they perceive as a tendency to extend credit only to those who don’t really need it, notes Purdue’s Gunderson. People working for the system believe they’re doing a good job of supporting agriculture, he says, noting that the system is charged with the responsibility of helping new and young farmers.

Another entity, the Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corp., also known as Famer Mac, works with lending institutions to provide credit to the agricultural sector. It’s a publicly traded company that serves as a secondary market in agricultural loans, including mortgages. It purchases loans and sells instruments backed by those loans and was chartered in 1988. Conterra, the alternative-funding company mentioned earlier in this article, -works with Farmer Mac and financial institutions to make real estate loans to farmers and ranchers in financial distress. The loans are designed to help borrowers get back on their feet in three to five years so that they would then qualify for regular bank loans.

Then there are the ag lending divisions at the large banks such as Wells Fargo, Chase and the Bank of the West, Martin says. “Lots of these big national banks are doing at least some ag lending,” he says. “Some, obviously, have bigger ag portfolios than others.”

Some regional banks focus on agriculture, Martin continues. “When you get into the middle of the corn belt, there are going to be some regional banks where traditional ag lending’s a huge part of what they do,” he says. Local banks in small towns get involved, too. “Most small community banks are going to have some kind of ag lending portfolio,” Martin notes. Hometown bankers can provide operating capital to some farmers, but only to those who haven’t experienced recent hiccups in revenue or expenses.

THE NON-BANKS

“Then you get into the non-bank lenders,” Martin observes. “A really good example of this is John Deere,” the tractor and equipment manufacturer. The company provides a tremendous amount of capital to rural America through equipment lending and also through other credit facilities, he says. In fact some observers estimate that John Deere is the largest lender to agriculture. Even so, the company usually doesn’t provide enough non-equipment credit to become the only lender a farmer would use, he says.

“Then you get into the non-bank lenders,” Martin observes. “A really good example of this is John Deere,” the tractor and equipment manufacturer. The company provides a tremendous amount of capital to rural America through equipment lending and also through other credit facilities, he says. In fact some observers estimate that John Deere is the largest lender to agriculture. Even so, the company usually doesn’t provide enough non-equipment credit to become the only lender a farmer would use, he says.

The same holds true with other lenders to agriculture, Martin says. Co-operatives, for example, lend money to agriculture even though they’re not banks. Typically, they begin by extending credit for products like seed, fertilizer or pesticides and then start making additional credit available to farms and ranches. In recent years, a large co-operative called CHS loaned hundreds of millions of dollars in addition to selling products on credit. Some large CHS loans went bad caused a ripple effect throughout the cooperative structure, Martin maintains. Other co-ops have looked at CHS and wondered if they’re moving too far outside their core competency. So now many co-ops are tying funding to products they’re selling.

Some other non-bank lenders have shown up in agriculture, and they fall into two categories, Martin says. One group is making real estate loans in agriculture, so their loan programs are geared to farmers looking to buy land or anything that can be secured by land. Conterra and Ag America are examples. Farmer Mac lends a lot of money against farmland, as well. So farmers who have agricultural land have a lot of access to capital and a lot of lenders who want to provide it, he says.

The second group of non-bank lenders is providing operating capital. “That is a very, very small club,” Martin says. “There’s really not anybody doing this on a regular basis – with just one or two exceptions.” Probably the biggest name among the exceptions is Ag Resource Management, usually known as ARM, he continues. ARM places a value on the potential productivity of a famer’s land. Then it looks at the crop insurance the farmer’s able to buy to protect the investment in that crop. ARM then lends part of the value of that crop insurance.

Let’s say a farmer can grow $10 million worth of crops, according to ARM’s projection,” Martin says. “You can get crop insurance to cover 80 percent,” he continues. “For a total crop failure, you will get $8 million for that crop.” Using a formula based on type of crop, location and type of crop insurance, ARM will lend some amount less than $8 million. “Their collateral is pretty rock solid,” Martin observes.

ARM uses a system to make sure farmers use the funds only for expenses related to growing the crop they’re using as collateral. “Their risk of not getting a crop in the ground that qualifies for the insurance is next to nothing,” Martin says. ARM offers differing interest rates, depending upon risk, in at least the high single digits or double digits, and they also charge fees. “So you’re going to be paying a lot, but they are the lender of last resort in agriculture right now,” he says, adding that ARM operates multiple offices has grown quickly.

Through lenders like ARM, the agricultural sector’s becoming familiar with alternative finance. But much remains to be done if alt fin pioneers want to venture into the sector. Those who do will encounter a complicated credit landscape, but one that offers opportunities for anyone willing to learn about unfamiliar business cycles and lifestyles.

Deal Flow in the Heartland — From Mississippi and Beyond

February 23, 2019

The political, cultural and economic abyss that separates the heartland from the coasts seems to grow deeper and wider with each passing day, and trying to reconcile the disparities can feel nearly hopeless. But differences among geographic locations aren’t nearly so well-defined or as troubling in the alternative small-business funding industry. What’s more, business opportunities can arise when localities differ.

The political, cultural and economic abyss that separates the heartland from the coasts seems to grow deeper and wider with each passing day, and trying to reconcile the disparities can feel nearly hopeless. But differences among geographic locations aren’t nearly so well-defined or as troubling in the alternative small-business funding industry. What’s more, business opportunities can arise when localities differ.

First the lay of the land: Members of the alt finance community agree that funders and brokers are concentrated in just a few geographic locales—Greater New York City, Southern California and South Florida. Those three areas probably generate more than 75 percent of the industry’s volume, according to Jared Weitz, CEO of United Capital Source and one of three co-chairs of the broker council recently formed by the Small Business Finance Association (SBFA).

Sorting out how the industry differs in various regions can prove challenging. The Internet is erasing regional quirks and alleviating the need for physical proximity, says Steve Denis, SBFA executive director. What’s more, every ISO and funder develops a slightly different way of doing business regardless of location, he notes.

However, to a great degree it’s a matter of tweaking a single general outline for navigating the industry no matter where the office or client is based. That’s partially because many members of the industry conduct business in every state or nearly every state.

That said, old-fashioned, small-town ethics can sometimes seem closer to the surface in shops operating far from the coasts. “We’re focused on the values of our organization—like doing what we say we’re going to do, maintains Tim Mages, chief financial officer at Expansion Capital Group, a funder and broker based in Sioux Falls, S.D. “Some of that maybe comes from the Midwest culture or upbringing.”

Outside the major population centers, the industry occasionally seems a little more “laid-back.” In a light-hearted example of a relaxed heartland approach to the alt funding business, Lance Stevens, an attorney who’s a co-founder of Brandon, Miss.-based TransMark Funding, claims he can underwrite a deal while driving his golf cart and listening to Bon Jovi—all while maintaining his under 5 handicap.

Everything can seem a little more slow in the heartland, where people have time to stop and say hello to strangers, says Weitz. “Some folks are like, ‘Hey, my mailbox is three miles from my house, I check my mail once a week. I do not email. I do not fax,’ ” he observes. “It’s a nice change.”

Interactions are often more informal between the coasts. “Being in the Midwest we don’t use a lot of the lingo and terminology from this space, such as ‘stacking,’” says Austin Moss, a managing partner at Strategic Capital in Overland Park, Kan. That lack of jargon may be good or bad, he admits, but instead the staff speaks in a more general, even “holistic,” financial language.

Then there’s the occasional need for the human touch in the heartland. Deals there are sometimes sealed in person, with an office-park conference room substituting for the community bank building on the town square where merchant used to take out loans. “It’s not a widespread trend, but a handful of the ISOs we do business with actually do face-to-face solicitation,” says Mike Ballases, CEO of Houston-based Accord Business Funding.

In line with that mini-trend, an ISO based in Southern California operates a Texas office that specializes in face-to-face encounters, according to Aldo Castro, Accord’s former vice president of sales and marketing. “It’s rather meaningful here,” he says of using the practice in Texas. “You get on the road and shake a hand. They put a face to a name.”

The process can work in reverse, too. A few of the larger local companies seeking funding from Strategic Capital make the journey to the broker-funder’s Overland Park, Kan., offices, Moss says. Bankers who serve as referral partners also like the opportunity to meet in person, he observes.

The personal encounters often strike Moss as “refreshing,” he admits. That’s because the vast majority of the company’s deals occur online and by phone and fax—all without ever seeing the client in person.

Although the desire for personal contact arises from time to time, most heartland deals don’t hinge upon it. “It’s not a big number, but we see it,” Ballases says of face-to-face meetings. “Could it be the wave of the future? Absolutely not.”

Moreover, for some in the industry, the need for face-to-face discussions barely registers. It’s just not about meeting in person, according to Mages. Instead, he cites the importance of other factors. “Speed, convenience and service are the key differentiators, and that’s all driven by data and analytics,” he declares. Partnerships also drive the company’s business, he notes.

Luck outweighs geography, too, in Mages’ view. “It’s more an issue of right place, right time,” he contends. Deals occur primarily when funders manage to attract business owners’ attention at exactly the time when capital’s needed, he contends.

Besides, lots of people tend to think in wide-ranging ways these days instead of in narrow, provincial modes, Mages continues. At Expansion Capital Group, he notes, executives have differing points of view because they come from commercial banking, investment banking, the Small Business Administration lending program and the credit card industry.

Besides, lots of people tend to think in wide-ranging ways these days instead of in narrow, provincial modes, Mages continues. At Expansion Capital Group, he notes, executives have differing points of view because they come from commercial banking, investment banking, the Small Business Administration lending program and the credit card industry.

At the same time, people tend to take an increasingly cosmopolitan approach to their jobs, according to Mages. He notes that executives at his company maintain contacts across the continent, often forged in earlier chapters of their careers.

Meanwhile, well-trained employees can use a phone call to gather the details they need and establish a consultative relationship without a thought for geography or the need for face-to-face meetings, Mages says.

However, geography can indeed play a role at least once in a while. In a few cases merchants prefer a funder with an address across town or at least in the home state. Sometimes business owners and referral partners choose local brokers or funders simply because their names sound familiar.

Strategic Capital, for example, does more business at home than anywhere else, Moss says. The company’s headquarters is in the portion of greater Kansas City that spills over from Missouri into the state of Kansas, making the location convenient to a major population center.

But despite the massive size of greater Kansas City, Strategic Capital remains the only alternative small-business funding option in the area—there just aren’t any other local providers, Moss says. It’s not like New York, where banks and merchants can choose from among many brokers and funders, he says.

That trend toward being the only game in town or one of just a few can hold true for most companies in the heartland, Moss maintains. A broker or funder based in Denver, for example, would probably have higher volume there than anywhere else, he notes.

Several reasons explain that geographic bias, Moss continues. “The employees live there and have contacts, and we’re part of the local associations and chambers,” he notes. “We work with just about all the banks in the area, and everyone knows who we are.” The company also handles local government bonds and local construction projects, he says.

Mages offers a different perspective. Only a few small-business owners in South Dakota choose Expansion Capital Group because they prefer dealing with a Midwestern company or because they’ve seen local press coverage or heard Expansion’s recruiting ads on the radio, he maintains.

Hometown, home state or regional preferences aside, executives at Accord emphasize the importance of the small-town approach of knowing their customers as well possible. For Ballases—the Accord chairman who started the company with Adam Beebe, who now serves as CEO—that means combining personal and impersonal approaches to underwriting.

Ballases views funders and brokers as falling into three categories. Some choose a personal, hands-on approach and don’t rely upon algorithms. A second category emphasizes automation. A third blends the personal and the automated. His organization falls into the latter, he says

For Accord, the personal comes into play because of what Ballases has learned in his decades in the banking business. He knows margins and growth rates in his applicants’ industries, and those factors aren’t often incorporated into algorithms, he says.

In fact, commercial banks have failed to learn to evaluate small businesses on their true merits, Ballases continues. Banks tend to underwrite small businesses, which he defines as those in need of $100,000 or less, by using a “skinnyed-down” version of how they underwrite big companies, which they base on general financial information. Instead, he counts on discipline, data and his 50 years of experience in commercial banking to evaluate a merchant on an individual basis.

At another company, TransMark Funding, Stevens and his partner draw upon legal and small-business experience to evaluate potential customers’ creditworthiness. “That causes us to focus on an applicant’s business model and their sustainability, which may boil down to personalities,” Stevens says. Transmark combines those factors with “a little bit of credit metrics” to come to decisions on applications.

The company’s mix of objective and subjective reasoning differs starkly from the thought process at most coastal funders, Stevens says. While his company gives most of the weight to the subjective and just a bit to the objective, big-city competitors tend to do the exact opposite, he says.

Of the last five MCA deals that Transmark funded, the merchants averaged 12 checks returned for insufficient funds per month, Stevens says, noting that he can make that statement “with a straight face.” Sometimes it’s been as high as 35 NSF checks per month for successful applicants. “Those people would not even get into the parking lot of a bank and would not get through the door of any MCA funder who’s using any sort of reasonable metrics,” he adds.

An anecdote helps explain the thinking. Suppose a restaurant has been operating for several years in a town of 50,000 and has amassed 2,200 “likes” on its Facebook page, Stevens suggests. “I’m in,” he exclaims, noting that it would take compellingly negative numbers to convince him that the business won’t survive if he helps it obtains capital to improve its positioning in its market.

The vignette illustrates that a business can do well in the community despite the merchant’s financial difficulties, Stevens says. However, the story doesn’t mean Facebook becomes the only determining factor, he continues. Positive factors for success include good location and marketing, he notes.

The principals at many companies funded by TransMark have credit scores in the low 500’s, Stevens continues. “That’s tough,” he says, “because they’re going to have a lot of history of not living up to their financial obligations.” But if someone with that credit score has personally guaranteed a lease on a storefront for the next two years, they may be unlikely to abandon the business. A big bank might look upon that merchant as insufficiently nimble because of the lease, but TransMark takes the opposite view, he says.

Even if a store, restaurant or contractor is “circling the drain” and about to shut down, TransMark may simply believe the owner has the character to make the business work. “Given our minute default rate, we’re right most of the time,” Stevens maintains, adding that banks see applicants as customers, and TransMark sees them as partners.

The business model requires peering into the future to see how the merchants will look after using perhaps $25,000 in capital to make improvements and while dealing with 18 percent holdback for the next six months, Stevens observes. “If they look strong, I need to fund them,” he says of the company’s prognostications.

To find ISOs who appreciate the TransMark model, the company seeks out purveyors of credit card merchant services, Stevens says. They encounter those merchant-services providers at trade shows and through “some general poking around,” he notes.

The merchant-services people often have long-standing relationships with merchants and thus can feed information into the TransMark way of viewing deals. “Tell me what it looks like when you walk into their store at 11 a.m.,” Stevens says to illustrate the kind of conversation he has with ISOs. “How is their signage?”

Besides understanding clients, it also pays to understand markets, and proximity can help with the latter, according to Ballases and Castro in Houston. “We have an affinity for Texas,” Castro says.

Many of the businesses based in Texas are vendors to people—like mechanics who fix cars or restaurants that feed people—not vendors to businesses, Ballases notes. Vendors who cater to people are better candidates for merchant cash advances than business-to-business companies are, he maintains.

“It’s just a huge state,” Castro declares. “We’ve got a thousand new residents moving to Texas every day.” Nearly 10 percent of the nation’s small businesses operate in The Lone Star State, he notes.

“There’s a convergence of the population growth, a low tax rate, low regulations, low cost of running a small business relative to national levels, and a great small-business environment,” Castro says of the Texas scene. “In addition, the healthcare industry is exploding here, and there are the ancillary businesses to healthcare.”

Meanwhile, the state’s Hispanic entrepreneurs remain under-served by alt funding ISOs, which presents a great untapped opportunity, Castro maintains. Funders who cater to those Hispanic merchants will find them loyal, he predicts. In Texas alone, Hispanic consumers spend half a billion dollars annually, he says.

To capitalize on that burgeoning market, Accord has assembled a team that can help Anglo ISOs bridge the cultural and linguistic gap, Castro says. “We do that every day,” he maintains. “We’re jumping on the phone with merchants and helping them get the funding they need to support the growth of their operations.” Those conversations with merchants do not put Accord in competition with ISOs, Castro notes. Accord does not maintain an inside sales staff and does all of its business through ISOs, he says.

Only a few of those ISOs are based in Texas, according to Ballases. Most of Accord’s ISOs operate from offices in the Northeast, with many in the other common geographic spots of South Florida and Southern California, he says. So that makes Accord a national company despite its emphasis on Texas, Ballases says.

Accord’s experience at home, combined with nationwide contacts in the industry, have convinced the company’s leadership that too many brokers remain unaware of the opportunities in Texas.

That’s why Accord is producing ads, videos, infographics, blogs and social media posts to alert those coastal ISOs to opportunities in Texas. The company even offers a tab called “FundTEX” on its website. “We’re getting the word out,” Castro says of the company’s effort to publicize his state.

Besides operating in areas sometimes overlooked on the coasts, heartland brokers and funders sometimes have to reinvent the industry almost from scratch. Brokers can find themselves teaching the business to potential investors outside the Big Three geographic locations, Moss says. In New York, investors already know the industry and use that familiarity to evaluate brokers, he says.

Brokers and funders also have to deal with the heartland’s lack of workers with industry experience. As the lone company in the market, Strategic Capital, for example, can’t find many prospective employees with previous jobs in the business, Moss notes. “There is no OnDeck or Yellowstone or RapidAdvance down the street to provide a talent pool for hiring,” he says.

That’s good and bad, Moss maintains. New hires don’t require re-training to lose habits that don’t fit the Strategic Capital way of working. But it’s difficult to find underwriters, accountants and other prospective employees with the right background. It doesn’t work to put new salespeople on straight commission because the “ramp-up” period takes longer with employees unfamiliar with the industry, he says.

The lack of local experience sometimes prompts brokers in the heartland to tap the Big Three areas for talent. Expansion Capital Group, for example, has a business development director in New York who came from another ISO, Mages says. Besides cultivating relationships in NYC, the business development expert makes frequent trips to Southern California and South Florida.

Meanwhile, members of the industry who tire of the rapid pace on the coasts might want to consider moving inland to fill the vacant jobs, sources suggest. After all, the heartland has its advantages, according to Moss. “Most people here have houses, and the cost of living is lower than in places like New York,” he says. A spacious five-bedroom house in Kansas City might cost less than a cramped apartment in New York, he notes.

To commute to the company’s suburban office, his typical employee jumps into a car in a climate controlled attached garage, cruises for half an hour or so on roads relatively free of traffic and parks in the lot a few steps outside his office building. It’s less stressful than crowding into a subway car, he notes.

The hinterland’s not as culturally barren as some might believe, Moss continues. The public hears “Kansas City” and they think of tornadoes, cows and the Wizard of Oz, he says. But the reality includes a downtown replete with skyscrapers and pro sports, not to mention lots of tech, healthcare and aerospace companies. “It’s like a mini-Chicago,” he notes.

But a retreat from the coasts may not be in the offing. Ballases expects that the majority of ISOs will continue to concentrate on the East Coast and West Coast because that’s where population growth remains strongest and thus provides the most opportunities. “It’s a numbers game,” he observes.

THE ABCs OF SBDCs

December 16, 2018 An often-overlooked national network of nearly a thousand Small Business Development Centers has the potential to help alternative funders cement relationships with existing clients and locate new ones. The centers, known as SBDCs, offer free or low-cost training and consultation to established and aspiring merchants and manufacturers.

An often-overlooked national network of nearly a thousand Small Business Development Centers has the potential to help alternative funders cement relationships with existing clients and locate new ones. The centers, known as SBDCs, offer free or low-cost training and consultation to established and aspiring merchants and manufacturers.

The earliest SBDCs have been around for four decades. The centers operate in conjunction with the Small Business Administration as public-private partnerships and serve about 1.5 million clients annually.

Centers help small-business owners evaluate ideas, organize companies, find legal assistance and obtain operating capital.

But not everyone knows all that. “The network is underutilized,” says Donna Ettenson, vice president of operations for Washington-based America’s SBDCs, which functions much like a trade association for the centers scattered across the nation. “We’re one of the best-kept secrets in the United States federal government.”

That means alternative funders can assist customers by simply informing them that the centers exist and can offer potentially beneficial services. Providing basic information on the SBDCs could become part of a consultative approach to selling that brings repeat business, especially with merchants who lack business skills or experience, observers suggest.

What’s more, alt funders who want to increase their chances of benefitting from SBDCs can go beyond merely providing clients with a rundown on the centers. The funders can become actively involved with the work of carried out at the centers.

One way of taking part is to contact nearby centers and offer to make presentations at seminars or workshops, Ettenson says. Funders could provide information to fledgling business owners on the instruments available through the alternative-funding industry, such as cash advances, loans and factoring, she suggests.

To get started, alternative funders can visit the America’s SBDC website, where they’ll find a search tool that provides contact information for their nearest centers, Ettenson says. From there, they could discuss possible connections with officials at the local centers, she advises.

To get started, alternative funders can visit the America’s SBDC website, where they’ll find a search tool that provides contact information for their nearest centers, Ettenson says. From there, they could discuss possible connections with officials at the local centers, she advises.

That involvement would not only provide exposure to merchants in need of capital but also to center officials who point merchants toward capital sources. If enough members of the alt funding industry took part, their work could eventually give rise to something akin to the lists of attorneys that some centers maintain, Ettenson says.

Centers often tap attorneys—perhaps quarterly—to lecture on a rotating basis on what type of business to form. That could mean organizing as a corporation, limited-liability partnership or some other form. In much the same way, funders could share their knowledge of instruments for obtaining capital.

Funders could emulate the lawyers who use the centers as a forum for soft marketing, Ettenson says. The speaker becomes a familiar face and can leave business cards that students could use to contact them as questions arise. However, speakers must provide general information and are prohibited from using speaking opportunities as blatantly self-promotional unpaid advertisements, she cautions.

What’s more, the centers have to exercise caution to avoid recommending specific attorneys, accountants or sources of capital because they could incur liability if events go sour and a service provider absconds to Bogata, Columbia, Ettenson points out. That keeps the centers “ecumenical,” in that they provide a list of professionals for clients to interview and rather than pointing to a single source.

Alternative funders can explore other ways to become involved with SBDCs, too. The national organization presents an annual trade show and professional development conference for service-center directors and service-center staff members who teach or consult with clients. Alternative funders who have taken booth space on the exhibition floor or made presentations in the accompanying conference include RapidAdvance, Breakout Capital, Kabbage and Newtek Business Services.

When America’s SBDCs issues a call for presentations at the annual conference, it receives approximately 300 applications for about 140 speaking slots. Some of the speakers come from the rosters of presenters at past shows, while companies newer to the trade show can purchase an entry-level sponsorship that includes booth space and the right to conduct a workshop.

The attendees at those annual conferences can tell their clients about the funders they encounter there. Attendees can also find out more about the alternative- funding industry and then pass that information along to merchants.

Some regional centers in states with large populations—such as California—can also hold conventions for their officials, says Patrick Nye, executive director for small business and entrepreneurship at the Los Angeles Regional SBDC Network, which is based at Long Beach City College. His state was planning its second statewide gathering this year and intends to do it again every other year. Alternative funders could participate, he says.

With so much going on at the centers, someone has to front the cash to keep the lights on. Local organizations are funded partly through federal appropriations administered by the SBA. “In order for the federal money to be pulled down, a matching non-federal dollar must be provided as well,” Ettenson says. The federal funds are apportioned based on the amount of matching funds the centers provide.

The matching funds usually flow from colleges, universities and state legislatures. “It’s a mix,” Ettenson says of the sources. Institutions of higher learning often meet part of their matching-fund goals by providing “in kind” resources—such as classrooms, services and instructors—instead of cash.

In the six states that administer the centers through their economic development departments, the state legislatures generally appropriate matching funds. In Texas, the representatives of the state’s four regional programs combine forces to lobby the legislature for matching funds, and that teamwork reduces the cost of their efforts in Austin.

The federal funds and matching funds support local and regional centers that belong to a network based on 62 host institutions. Of the 62, six operate through the economic development departments of state governments. They’re in Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, West Virginia, Minnesota and Colorado. The rest of the host institutions are mostly universities or community colleges. Some are based in economic development agencies.

One can think of the regional centers as something akin to corporate headquarters and the local centers as retailers, says Nye, who administers the Southern California regional center. The local centers under his regional’s jurisdiction are located in only three counties but pull in the sixth-largest share of funding because of Southern California’s huge population, he notes.

The local service centers provide training and consulting for entrepreneurs starting or expanding their enterprises. About 60 percent of the clients are already in business. Of the 40 percent who don’t own a business, about half launch one after receiving assistance from an SBDC, Ettenson says.

The centers don’t charge for consulting services, and the fees for training are just large enough to cover expenses. The training fees usually remain in the centers that provide the instruction where they’re used to cover expenses like buying computers.

In Southern California centers, the business advisors are usually under contract and have knowledge to share from their experience in business, marketing, banking, social media, consulting or other realms, says Nye. Not many college instructors work in the centers, he notes, adding that the centers are monitored to avoid conflicts of interest among advisors.

To track how well advisors are performing, the national organization produces economic impact statements by interviewing thousands of clients. Interviews generally take place two years after consulting sessions. That should provide enough time to get results, Ettenson says

Thus, America’s SBDCs this year surveyed clients who received services in 2016. Those long-term clients received $4.6 billion in financing, while last year the clients surveyed who got underway in 2015 had received $5.6 billion in financing. She could not break down that financing by categories like banks and non-banks.

Discussing those surveys, Ettenson offers some details. “If you talk to us for two minutes, we don’t consider you a client,” she emphasizes. The SBDC definition of what constitutes a client calls for at least one hour of one-to-one consulting or at least one two- hour training session, she says. The organization defines “touches” as people with less exposure, such as those who call on the phone with a question.

When an SBDC client needs funding, officials at the centers have no qualms about including alternative funders in their recommendations to clients who are seeking funds, says Ettenson. “We don’t exclude anybody in any way, shape or form unless there’s some reason to think they’re fraudulent,” she notes.

But malfeasance isn’t the worry it once was, Ettenson asserts, noting that alternative funders have gained credibility in the last five or so years as they began policing their own industry. “They’ve learned to keep track of who’s in their space and how they’re operating,” she says.

Alternative financing has established a niche that benefits small-business people who know how to use it, Ettenson maintains. “They understand that they’re borrowing money for a short period of time and it’s going to cost you a fair amount,” she says. “It’s a short-term bridge to get to whatever your goal is.” Merchants seeking funders should learn the differences among alternative funders—whom she says all operate a little differently from each other—to choose their best option.

And opportunity for alternative funders may abound at the centers in the near future. Nye cites the two biggest goals for his centers as new business starts and capital infusion. Center advisors help develop business plans that aid clients in obtaining financing, he says. Last year, his region received a little over $4 million from the SBA and used it to help start 365 new businesses and raise $148 million in capital infusions. Those efforts created 1,700 jobs, he says.

Is Small Business Lending Stuck in the Friend Zone?

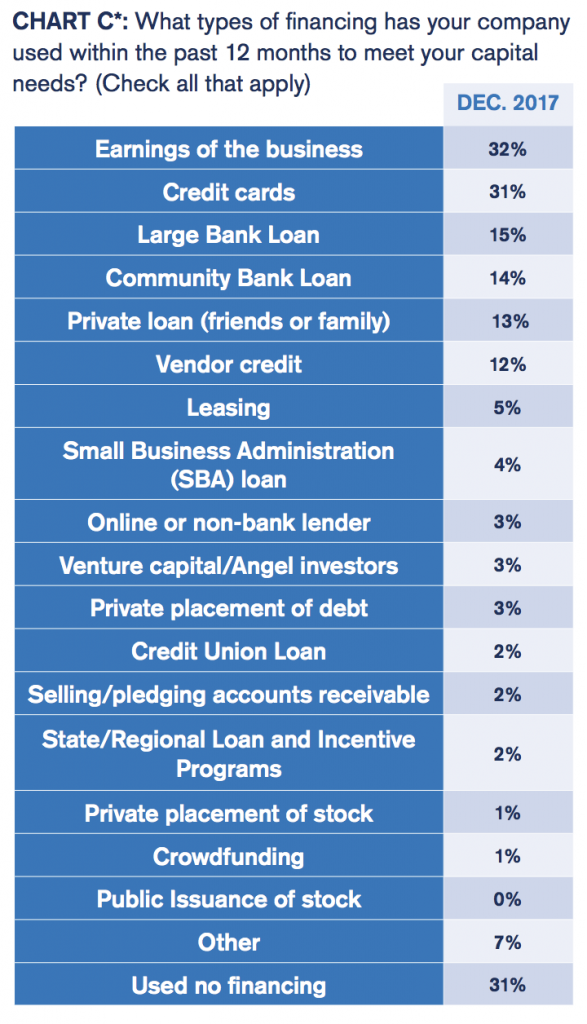

October 23, 2018 Small-business owners have lots of places to go for capital, and the alternative small-business funding industry doesn’t exactly top the list, recent research shows. In fact, entrepreneurs claim they’re more than four times as likely to receive funding from a friend or family member than from an online or non-bank source.

Small-business owners have lots of places to go for capital, and the alternative small-business funding industry doesn’t exactly top the list, recent research shows. In fact, entrepreneurs claim they’re more than four times as likely to receive funding from a friend or family member than from an online or non-bank source.

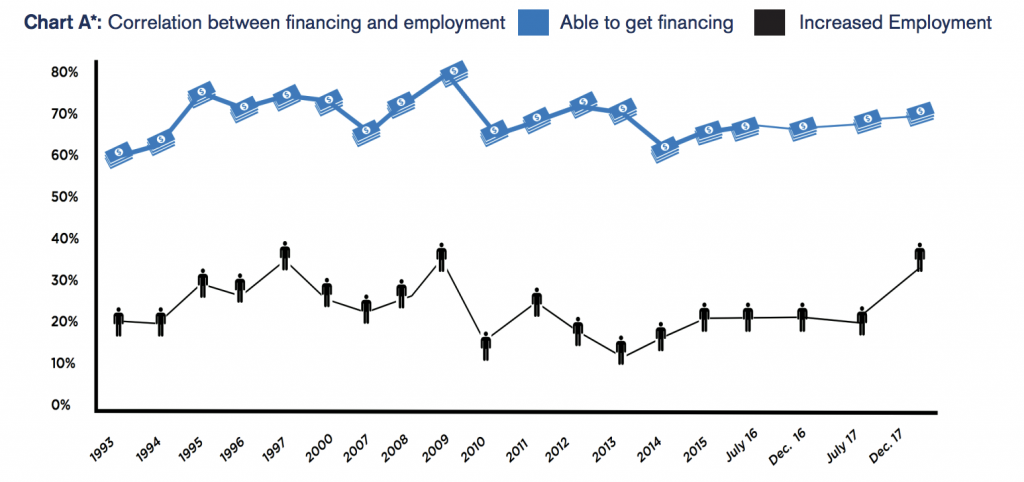

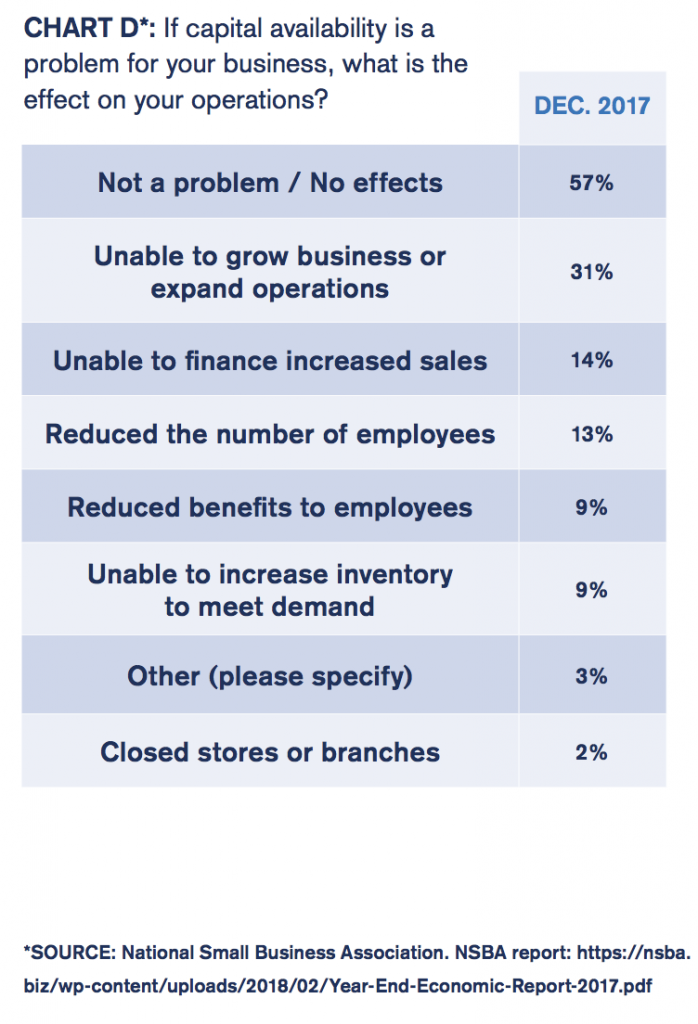

That bit of intelligence comes from the National Small Business Association‘s 2017 Year End Economic Report, the most recent from the Washington-based trade group. Thirteen percent of the entrepreneurs who responded to the survey received loans from family or friends in the preceding 12 months, while 3 percent obtained funding from online or non-bank lenders, the report says.

But some variables come into play. Shopkeepers and restaurateurs are more likely to rely on friends and family for financing during their first five years in business, says Molly Brogan Day, the NSBA’s vice president of public affairs and a 15-year veteran of the survey. The association’s members, who account for many – but not all – of the respondents tend to have been in business longer than non-members so the actual percentage of all owners receiving funds from family or friends could well be higher than the survey indicates, she notes.

In fact, the average NSBA member started his or her business 11 years ago – a fairly long time for the sector, Day says. The association attracts well-established merchants partly because the trade group concentrates on advocacy and lobbying in the nation’s capital, Day notes. “There’s not a lot of networking, there’s not a ton of resources or educational offerings,” she says of the association. In other words, the organization’s emphasis tends to attract prospective members who have been in business long enough to see the results of laws and regulation instead of newcomers still struggling daily to establish themselves, she observes.

Anyway, it’s also worth noting that small-business owners appear nearly as likely to approach family or friends for cash as to petition large banks for funding, Day says, noting that 13 percent turn to friends and family, while 15 percent manage to obtain loans from large banks. To her, that indicates that banks just aren’t lending to small businesses as frequently as they should – a notion that should sound familiar to anyone in the alternative small-business funding industry.

Unsurprisingly, the association’s research indicates bank lending declined as the Great Recession made itself felt in 2007 and 2008. Before that, nearly 50 percent of merchants responding to the survey reported they had recently qualified for loans from big banks, small banks or credit unions, the research shows. “Now it’s pretty consistently a percentage in the low 30’s,” Day says. “People really need these loans.”

Lending by banks hit another snag in 2012 when new regulation and legislation, including the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, made itself felt. “There was such a massive overcorrection in the banking industry that it’s still really difficult for small businesses to get loans,” Day says.

Moreover, banks were granting fewer “character-based” loans even before the double whammy or recession and regulation, Day observes. Instead of employing the older practice of assessing the intangible virtues of a business owner well-known in the community, bankers began applying a more formulaic approach to evaluating loan applications based on credit scores and other quantifiable variables, she says.

That switch to numbers-oriented decisions proved detrimental for many entrepreneurs. “A lot of small business owners don’t look great on paper,” Day admits. Even a great business plan might not convince bankers to loosen their purse strings these days, she notes.