Bad Merchants: Lies, Fraud, and Hard Times

Critics seldom tire of bashing alternative finance companies, but bad behavior by merchants on the other side of the funding equation goes largely unreported. Behind a veil of silence, devious funding applicants lie about their circumstances or falsify bank records to “qualify” for advances or loans they can’t or won’t repay. Meanwhile, imposters who don’t even own stores or restaurants apply for working capital and then disappear with the money.

Critics seldom tire of bashing alternative finance companies, but bad behavior by merchants on the other side of the funding equation goes largely unreported. Behind a veil of silence, devious funding applicants lie about their circumstances or falsify bank records to “qualify” for advances or loans they can’t or won’t repay. Meanwhile, imposters who don’t even own stores or restaurants apply for working capital and then disappear with the money.

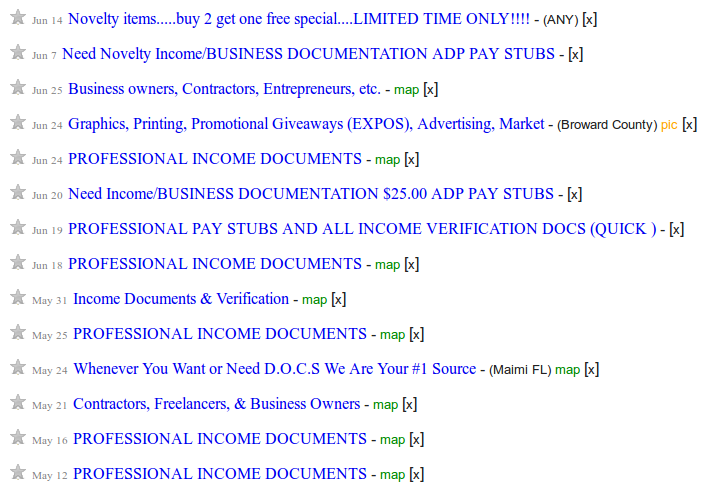

“People advertise on craigslist to help you commit fraud,” declared Scott Williams, managing member at Florida-based Financial Advantage Group LLC, who helped start DataMerch LLC to track wayward funding applicants. “Fraud’s a booming business, and every year the numbers seem to increase.”

Deception’s naturally on the rise as the industry continues to grow, according to funders, industry attorneys and collections experts. But it’s also increasing because technology has made it easy for unscrupulous funding applicants to make themselves appear worthy of funding by doctoring or forging bank statements, observers agreed.

Some fraud-minded merchants buy “novelty” bank statements online for as little as $5 and fill them out electronically, said David Goldin, president and CEO of Capify, a New York-based funder formerly called AmeriMerchant, and president of the SBFA, which in the past was called the North American Merchant Advance Association.

To make matters worse, dishonest brokers sometimes coach merchants on how to create the forgeries or modify legitimate records, Goldin maintained. Funders have gone so far as to hire private investigators to scrutinize brokers, he said.

But savvy funders can avoid bogus bank statements, according to Nicholas Giuliano, a partner at Giuliano, McDonnell & Perrone, a New York law firm that handles collections. Funders can protect themselves by remaining skeptical of bank records supplied by applicants. “If the merchant cash advance company is not getting them directly from the source, they can be fooled,” Giuliano said of obtaining the documents from banks.

Another attorney at the firm, Christopher Murray, noted that many funders insist upon getting the merchant’s user name and password to log on to bank accounts to check for risk. That way, they can see for themselves what’s happening with the merchant.

Besides banking records, funders should beware of other types of false information the can prove difficult to ferret out and even more difficult to prove, Murray said. For example, a merchant who’s nine or ten months behind in the rent could convince a landlord to lie about the situation, he noted. The landlord might be willing to go along with the scam in the hope of recouping some of the back rent from a merchant newly flush with cash.

Merchants can also reduce their payments on cash advances by providing customers with incentives to pay with cash instead of cards or by routing transactions through point of sale terminals that aren’t integrated onto the platform that splits the revenue, said Jamie Polon, a partner at the Great Neck, N.Y.-based law firm of Mavrides, Moyal, Packman & Sadkin, LLP and manager of its Creditors’ Rights Group. A site inspection can sometimes detect the extra terminals used to reduce the funder’s share of revenue, he suggested.

In a ruse they call “the evil twin” around the law offices of Giuliano, McDonnell & Perrone, merchants simply deny applying for the funding or receiving it, Giuliano said. “Suddenly, the transaction goes bad, and they deny they had anything to do with it,” he said. “It was someone who stole the merchant’s identity somehow and then falsified records.”

In other cases, merchants direct their banks not to continue paying an obligation to a funder, or they change to a different bank that’s not aware of the loan or advance, according to Murray. They can also switch to a transaction processor that’s not aware of the revenue split with the funder. Such behavior earns the sobriquet “predatory merchant,” and they’re a real problem for the industry, he said.

Occasionally, merchants decide to stop paying off their loans or advances on the advice of a credit consulting company that markets itself as capable of consolidating debt and lowering payments, Giuliano said. “That’s a growing issue,” agreed Murray. “A lot of these guys are coming from the consumer side of the industry.”

The debt consolidator may even bully creditors to settle for substantially less than the merchant has agreed to pay, Murray continued. Remember that in most cases the merchants hiring those companies to negotiate tend to be in less financial trouble than merchants that file for bankruptcy protection, he advised.

“More often than not, they simply don’t want to pay,” he said of some of the merchants coached by “the credit consultants.” They pay themselves a hundred thousand a year, and everyone else be damned. You continue to see them drive Humvees.”

Merchants sometimes take out a cash advance and immediately use the money to hire a bankruptcy attorney, who tries to lower the amount paid back, Murray continued. However, such cases are becoming rare because bankruptcy judges have almost no tolerance for the practice and because underwriting continues to improve, he noted.

Still, it’s not unheard of for a merchant to sell a business and then apply for working capital, Murray said. In such cases, funders who perform an online search find the applicant’s name still associated with the enterprise he or she formerly owned. Moreover, no one may have filed papers indicating the sale of the business. “That’s a bit more common than one would like,” he said.

In other cases the applicant didn’t even own a business in the first place. “They’re not just fudging numbers – they’re fudging contact information,” said Polon. “It’s a pure bait and switch. There wasn’t even a company. It’s a scheme and it’s stealing money.”

Whatever transgressions the merchants or pseudo-merchants commit, they seldom come up on criminal charges. “It is extremely, extremely rare that you will find a law enforcement agency that cares that a merchant cash advance company or alternative lender has been defrauded,” Murray said. It happens only if a merchant cheats a number of funders and clients, he asserted. “Recently, a guy made it his business to collect fraudulent auto loans,” he continued. “That’s a guy who is doing some time.”

However, funders can take miscreants to court in civil actions. “We’re generally successful in obtaining judgments,” said Giuliano. “Then my question is ‘how do you enforce it?’ You have to find the assets.” About 80 percent of merchants fail to appear in court, Murray added. Funders may have to deal with two sets of attorneys – one to litigate the case and another to enforce the judgment. Even merchants who aren’t appearing in court to meet the charges usually find the wherewithal to hire counsel, he said.

Funders sometimes recover the full amount through litigation but sometimes accept a partial settlement. “Compromise is not uncommon,” noted Giuliano. Settling for less makes more sense when the merchant is struggling financially but hasn’t been malicious, said Murray.

To avoid court, attorneys try to persuade merchants to pay up, said Polon. “My job is to get people on the phone and try to facilitate a resolution,” he said of his work in “pre-litigation efforts,” which also included demand letters advising debtors an attorney was handling the case.

But it’s even better not to become involved with fraudsters in the first place. That’s why more than 400 funding companies are using commercially available software that detects and reduces incidence of falsified bank records, said a representative of Microbilt, a 37-year-old Kennesaw, Ga.-based consumer reporting agency that has supplied a fraud-detection product for nearly four years.

But it’s even better not to become involved with fraudsters in the first place. That’s why more than 400 funding companies are using commercially available software that detects and reduces incidence of falsified bank records, said a representative of Microbilt, a 37-year-old Kennesaw, Ga.-based consumer reporting agency that has supplied a fraud-detection product for nearly four years.

“Our system logs into their bank account and draws down the various data points, and we run them through 175 algorithms,” he said. “It’s really a tool to automate the process of transferring information from the bank to the lender,” he explained.

The tools note gross income, customer expenditures, loans outstanding, checks returned for non-sufficient funds and other factors. Funders use the portions of the data that apply to their risk models, noted Sean M. Albert, MicroBilt’s senior vice president and chief marketing officer.

Funders pay 25 cents to $1.25 each time they use MicroBilt’s service, with the rate based on how often they use it, Albert said. “They only pay for hits,” he said, noting that they don’t charge if information’s not available. Funders can integrate with the MicroBilt server or use the service online. The company checks to make sure that potential customers actually work in the alternative funding business.

MicroBilt is testing a product that gathers information from a merchant’s credit card processing statement to analyze ability to repay excessive chargebacks reflected in the statements could spell trouble, and seasonality in receipts should show up, he noted.

Additional help in avoiding problem merchants comes from the Small Business Finance Association, which maintains a list of more than 10,000 badly behaving funding applicants, said the SBFA’s David Goldin. The nearly 20 companies that belong to the trade group supply the names.

SBFA members, who pay $3,000 monthly to belong, have access to the list. According to Goldin, the dues make sense because preventing a single case of fraud can offset them for some time, he maintained. Besides, associations in other industries charge as much as $10,000 a month, he added.

Another database of possibly dubious merchants, maintained by DataMerch LLC, became available to funders in July, according to Scott Williams, who started the enterprise with Cody Burgess. It became integrated with the deBanked news feed by early October, causing the number of participating funders to double to a total of about 40, he said. The service is free now, but will carry a fee in the future.

It’s not a blacklist of merchants that should never receive funding again, Williams emphasized. Businesses can return to solvency when circumstances can change, he noted. That’s why it’s wise to regard the database as an underwriting tool. In addition, merchants can in some cases add their side of the story to the listings.

Funding companies directly affected by wayward merchants can contribute names to the list, Williams said. About 2,500 merchants made the list within a few months of its inception, he noted. “We’re super happy with our numbers,” he said of the database’s growth.

Many merchants find themselves in the database because of hard times. Of those who land on the list because of fraud, perhaps 75 percent actually own businesses and about 25 percent are con artists applying for funding for shell companies, Williams said.

So far, only direct funders – not brokers or ISOs – can get access to the database, he continued, noting that DataMerch could rethink the restriction in the future. “We don’t want hearsay from a broker who might not know the full scope of the story,” he said.

DataMerch might grant brokers and ISOs the right to read the list to avoid wasting time pitching deals to substandard merchants, but the company does not intend to enable members of those groups to add merchants to the database, Williams said.

Williams sees a need for the new database because smaller companies can’t afford belonging to the SBFA. The association also tracks deals about to become final, which could prevent double-funding but makes some users uncomfortable because they don’t want to disclose their good merchants, Williams said.

Although dishonesty’s sometimes a factor, merchants often go into default just because of lean times, Jamie Polon, the attorney, cautioned. A restaurant could close, for example, because of construction or an equipment breakdown. “Were they not serving dinner anymore, or was there something much deeper going on?” he said. Fraud may play a role in 10 percent to 20 percent of the collections cases his law firm sees, he noted. More than 95 percent blame their troubles on a downturn in business, and the rest claim they didn’t understand the contract, he said.

Although dishonesty’s sometimes a factor, merchants often go into default just because of lean times, Jamie Polon, the attorney, cautioned. A restaurant could close, for example, because of construction or an equipment breakdown. “Were they not serving dinner anymore, or was there something much deeper going on?” he said. Fraud may play a role in 10 percent to 20 percent of the collections cases his law firm sees, he noted. More than 95 percent blame their troubles on a downturn in business, and the rest claim they didn’t understand the contract, he said.

To understand the downturn, it’s important to amass as much information about the merchant as possible, said Mark LeFevre, president and CEO of Kearns, Brinen & Monaghan, a Dover, Del.-based collections agency that works with funders. That information sheds light on a merchant’s ability to repay and could help determine what terms the merchant can meet, he said.

Timeliness matters because the sooner a creditor takes action to collect, the greater the chance of recouping all or most of the obligation, LeFevre maintained. When distress signals arise – such as closing an ACH account or a spate of unreturned phone calls – it’s time to place the merchant with a collections expert, he advised.

LeFevre’s company also traces a troubled merchant’s dwindling assets to help the funder receive a fair share. Funders can sometimes recover all or most of what they pay a collection agency by imposing fees on the merchant, he noted.

Pinning the collection fees to merchants in default makes sense because that’s where the guilt often resides, observers said. It’s part of balancing the bad behavior equation, they agreed.