Bless You, Fund Me: What Words Predict About Loan Performance

Way back in 2006 when I was just a baby merchant cash advance* underwriter, I encountered a book store that was borderline qualified. The final phone interview would make or break their approval so I grabbed my pen and paper and dialed their number.

Way back in 2006 when I was just a baby merchant cash advance* underwriter, I encountered a book store that was borderline qualified. The final phone interview would make or break their approval so I grabbed my pen and paper and dialed their number.

I went through the checklist of questions and they passed. But what really convinced me that it was a deal worth doing was the amount of times the owners made references to God. They were clearly religious people which indicated to me that they were probably also of high moral character. It didn’t matter what religion it was or if their beliefs aligned with mine, I was simply captivated by their values.

After approving the deal and funding them, they actually mailed me a handwritten letter to express their gratitude. It concluded with, “God Bless You!” and I hung it up on the wall of my cubicle to remind myself of the good I was doing for small businesses.

A few weeks later, the payments stopped. All of their contact numbers were disconnected and the owners of the store could not be located. They completely disappeared along with almost all of the money. Looking up at the note on my wall, a shiver went up my spine. Had I been duped? And did they use religion as a tool to influence my decision?

I thought that surely they must’ve encountered legitimate financial difficulty but I believed that even if so, people with their values would’ve been more forthcoming about it. Instead they just took the money and split and were never heard from again.

I learned a lesson about being emotionally influenced on a deal and it turns out there were clues this outcome might happen all along.

Bless you

In a study titled, When Words Sweat: Written Words Can Predict Loan Default, Columbia University professors Oded Netzer and Alain Lemaire, and University of Delaware professor Michal Herzenstein analyzed the text of more than 18,000 loan requests made on Prosper’s website. Applicants that used the word God were 2.2x more likely to default on their loans. And the phrase Bless you correlated higher on the default scale as well, though not as high as other non-religious words.

On the list of words more likely to be mentioned by defaulters are, I promise, please help, and give me a chance. Statistics actually show that someone promising to pay is less likely to pay than someone that doesn’t explicitly promise.

Among the other more common words likely to be mentioned by defaulters is hospital. This word holds special significance to me because in my last year as a sales rep, almost all of my underperforming accounts were supposedly due to the business owners or their family members being in the hospital.

Among the other more common words likely to be mentioned by defaulters is hospital. This word holds special significance to me because in my last year as a sales rep, almost all of my underperforming accounts were supposedly due to the business owners or their family members being in the hospital.

And it wasn’t just me. It seemed like every deal that was going bad in the office involved the hospital. Any time one of us was due to contact an account with an issue, we made bets that a hospital would come up in the story. (Seb, if you’re reading this, apparently it’s not a coincidence.)

I express no opinion regarding whether or not their stories were true, but statistics show that borrowers that mention hospital are more likely to default.

In the study’s Abstract, the professors wrote:

Using a naïve Bayes analysis and the LIWC dictionary of writing styles we find that those who default write about financial hardship and tend to discuss outside sources such as family, god and chance in their loan request, while those who pay in full express high financial literacy in the words they use. Further, we find that writing styles associated with extraversion, agreeableness and deception are correlated with default.

While the study focused on Prosper, their almost identical competitor, Lending Club, may have realized this trend earlier. In March 2014, Lending Club announced that investors would no longer be able to view the free-form writing portion of the borrower loan application. Citing “privacy reasons,” investors lost a valuable clue into the repayment probability of their notes.

But would it really have helped? The researchers wrote:

Using an ensemble learning algorithm we show that leveraging the textual information in loan requests improves our ability to predict loan default by 4-5.7% over the traditionally used financial information.

Nothing to see here folks, move along and approve

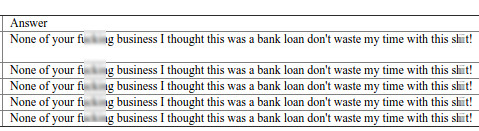

Curiously, Lending Club doesn’t want its investors to have access to a data point with such significant importance. Perhaps it’s because of disasters like this, where one borrower used the free-form writing section to spew profanities. Ironically, the loan was approved and issued anyway.

For tech-based platforms like Lending Club however, they noticed the “story” aspect of a loan had become less relevant because of overwhelming investor demand. Investors weren’t evaluating the written portion of the loan application as much anymore. According to their blog post at the time of the announcement, “Fewer than 3% of investors currently ask questions and only 13% of posted loans have answers provided by borrowers. Furthermore, loans are currently funding in as little as a few hours – well before borrower answers and descriptions can be reviewed and posted.”

It had become all algorithms and APIs where loans were fully funded by investors before the written portions could even be published on the website. Had anyone actually taken the time to read the above loan application answers, they probably wouldn’t have allocated money towards it.

But while removing the storyline from the data might give investors fewer methods to detect a good loan, it could actually protect them from getting drawn into a bad loan.

One of the authors of the above referenced study, Professor Michal Herzenstein of University of Delaware, found in 2011 that borrowers could manipulate lenders into not only approving them, but giving them more favorable terms.

You can trust me 😉

In a story that appeared on UD’s website in 2011, titled Good Storytelling May Trump Bad Credit, Herzenstein’s research discovered that borrowers who constructed a trustworthy picture of themselves “could lower their costs by almost 30 percent and saved about $375 in interest charges by using a trustworthy identity.”

The study referred to six possible categories or identities that borrowers would try to impress upon lenders to describe themselves (trustworthy, successful, economic hardship, hardworking, moral, religious). The story explains:

The more identities the borrowers constructed, the more likely lenders were to fund the loan and reduce the interest rate but the less likely the borrowers were to repay the loan – 29 percent of borrowers with four identities defaulted, where 24 percent with two identities and 12 percent with no identities defaulted.

It’s a case of measurable borrower manipulation.

“By analyzing the accounts borrowers give and the identities they construct, we can predict whether borrowers will pay back the loan above and beyond more objective factors like their credit history,” said Herzenstein. “In a sense, our results offer a method of assessing borrowers in ways that hark back to the earlier days of community banking when lenders knew their customers.”

Today’s tech-based lenders that are dead set on removing this human aspect from the equation may be taking a shortsighted approach after all as they evidently still struggle to make predictions with their numbers-only approach.

For example, a poster on the Lend Academy forum recently wrote this to me about early defaults in today’s algorithmic environment, “It would be nice if LC could predict who is going to default in the first few months of the loan and deny them, but I don’t think that is entirely possible.”

It reminded me of a big merchant cash advance deal I approved years back that passed all of the qualifying criteria with flying colors and still defaulted on the very first day. The merchant’s response to why he defaulted on day one? He felt like screwing us over… “Come sue me,” he said.

In a later meeting to review the deal’s paperwork, a group of managers agreed that I had done all I could to make the approval decision except one. I failed to account for the asshole factor.

Far from satire, it is not uncommon for financial companies to refer to an asshole factor in some regard. It’s a very subjective variable but it can make all the difference between an applicant that’s going to pay and one that’s not. Suddenly none of the hard data matters.

Is the applicant an asshole?

In a recent blog post by loan broker Ami Kassar, titled The Single Most Important Rule in Our Company, Kassar wrote, “if a customer, employee, or partner acts like a jerk – we don’t want to do business with them. If you want to be less diplomatic, you can call the rule – the no ###hole rule.”

In a recent blog post by loan broker Ami Kassar, titled The Single Most Important Rule in Our Company, Kassar wrote, “if a customer, employee, or partner acts like a jerk – we don’t want to do business with them. If you want to be less diplomatic, you can call the rule – the no ###hole rule.”

In many circumstances, the measure of someone being an asshole is relative to another person’s perception. There’s even an entire book on that subject if you’re interested. But what’s trickier, is that according to some studies, being an asshole is a positive thing in business. Would that also make them better borrowers statistically?

Referring back to the original cited study, one has to wonder if there might potentially be a list of words that more closely correlate with being an asshole. I don’t think anyone’s ever examined the Prosper data for that before.

You might not be able to quantify asshole-ishness from the text, but something as basic as a person’s pronouns can speak volumes about their personality or intentions. According to Professor James Pennebaker in the Harvard Business Review:

A person who’s lying tends to use “we” more or use sentences without a first-person pronoun at all. Instead of saying “I didn’t take your book,” a liar might say “That’s not the kind of thing that anyone with integrity would do.” People who are honest use exclusive words like “but” and “without” and negations such as “no,” “none,” and “never” much more frequently.

But saying “I” over “we” doesn’t necessarily make you less of a liar. Pennebaker discovered that depressed people use the word “I” much more often than emotionally stable people.

Being emotionally stable would probably make for a better borrower than a depressed one, but with all these influential and conflicting language clues, how can an underwriter possibly make the right choice?

For instance, if the following line appeared on the free-form writing portion of an application, how should it be interpreted?

Using all of the mentioned research as a guide, I’m inclined to consider the applicant a: trustworthy depressed lying asshole that’s not going to pay.

I = Depressed

We = Liar

God = 2.2x more likely to default

Have always been able to pay back = trustworthy

Hurry up and fund me = asshole

We could easily get caught up in the language here and ignore the obvious positives about this hypothetical applicant, such that they have an 800 FICO score and a solid six figure income. Shouldn’t that weigh more heavily? It’s easy to get distracted.

Perhaps Lending Club’s removal of the free-form writing section was for the investors’ own good. Even the borrower that repeatedly wrote, “None of your f**king business I thought this was a bank loan don’t waste my time with this sh**t!” is still current on all their payments after two and a half years.

To brokers like Kassar, the asshole factor is not so much about the likelihood of default anyway, but peace of mind. “Why invest emotional energy in putting up with shenanigan’s when there are so many good people who need our help,” he wrote.

Word is bond?

Regardless of what one study revealed about applicants that invoked God said about the likelihood of default, declining applicants on the basis of writing or talking about God could certainly be argued as religious discrimination. In many instances, religion is a protected class. Sometimes you have to ignore correlations because they can be deemed discriminatory.

One thing is for sure though, back in 2006 the upstanding characters I had created in my mind about the religious book store owners were upended when they disappeared into the night with all the money. Their words got in my head and I approved them perhaps because of it.

Years later, an asshole defaulted on the first day and not long after that, there would be a mysterious spate of accounts whose poor performance would be attributed to supposed hospital related events.

What’s buried in a person’s words? The answers allegedly. I promise…

Last modified: June 7, 2015Sean Murray is the President and Chief Editor of deBanked and the founder of the Broker Fair Conference. Connect with me on LinkedIn or follow me on twitter. You can view all future deBanked events here.