Legal Briefs

Another COJ Bill In New York Added To The Pile

May 14, 2019 Three members of the New York State Assembly want to make it illegal for a confession of judgment to be entered in the state against non-New York debtors. The debtor would also be required to be a resident of the county in which the COJ is filed. The authors behind Bill A07500, introduced on May 7th, plainly state that it is a reaction to stories that were published in Bloomberg Businessweek. (Questionable stories at that: See deBanked coverage)

Three members of the New York State Assembly want to make it illegal for a confession of judgment to be entered in the state against non-New York debtors. The debtor would also be required to be a resident of the county in which the COJ is filed. The authors behind Bill A07500, introduced on May 7th, plainly state that it is a reaction to stories that were published in Bloomberg Businessweek. (Questionable stories at that: See deBanked coverage)

“This measure is in response to recent press reports regarding creditors that execute confessions of judgment in New York State even though the associated agreement or debtor have no nexus to the State,” a memo attached to the bill states. Sign Here to Lose Everything, the Businessweek series authored by Zachary R. Mider and Zeke Faux, are cited in the footnotes.

The measure is merely the latest weapon unveiled in a wave of proposed legislation aimed at small business financing in New York this year. Here’s a recap of what’s pending now:

- A07500 – Seeks to ban COJs being entered against non-New York debtors.

- A03636 – Seeks to ban COJs from financial contracts.

- A03637 – Seeks to classify merchant cash advances as loans.

- A03646 – Seeks to establish a task force to investigate New York City marshals and their connection to “predatory lenders” and consider the feasibility of abolishing the city marshal program.

- A03638 – Seeks to apply consumer usury protections to small businesses.

Direct Lending Investments Had Over 950 Investors

April 16, 2019 Documents filed in a New York Supreme Court case by the receiver managing Direct Lending Investments (DLI), revealed that DLI had more than 950 investors worldwide with collective investments on the books totaling over $780 million.

Documents filed in a New York Supreme Court case by the receiver managing Direct Lending Investments (DLI), revealed that DLI had more than 950 investors worldwide with collective investments on the books totaling over $780 million.

For those wondering what’s happened since word of the hedge fund’s shocking demise, Bradley D. Sharp of Development Specialists, Inc. has been appointed to serve as permanent receiver for the fund’s estate. In the New York Supreme Court case, which coincidentally involves VOIP Guardian Partners, Sharp explained that they are currently dealing with a number of “urgent matters arising during the first two weeks of the SEC Action, including but not limited to: securing the business assets and cash of the receivership estate; taking custody of records of the Receivership Entity, including records held by third parties; filing notices of the receivership in approximately 50 district courts across the country; addressing insurance and loan portfolio matters; providing notice to and responding to inquiries from investors; and other similar pressing matters.”

Regarding the $192 million owed to DLI by VOIP, “the Receiver is evaluating enforcement and collection of the VOIP Guardian Loans as against VOIP Guardian Partners I LLC in light of its pending bankruptcy proceeding, and the underlying loans comprising the collateral for the VOIP Guardian Loans.”

Recovering the $192 million in bankruptcy from VOIP may prove difficult. deBanked determined that $159 million of it was actually loaned by VOIP to other companies internationally, including Telacme Ltd in Hong Kong and Najd Technologies Ltd in United Arab Emirates. At the time of its reporting, the websites for both companies had been taken down from the web. The website for Telacme has since been restored.

A class action lawsuit was filed against DLI, its former chief executive Brendan Ross, and others on April 1st.

Additional documents filed in the case on 4/12/19 can be viewed here:

DLI-41219-15.pdf

DLI-41219-16.pdf

Lots of Tech Buzzwords, Scary Problems

April 16, 2019 A federal regulator cut through the shield of fintech buzzwords on Monday when it announced that a darling of online lending valued at $2 billion, failed to properly handle rudimentary loan practices. The lender is Chicago-based Avant, who reportedly settled with the FTC for $3.85 million.

A federal regulator cut through the shield of fintech buzzwords on Monday when it announced that a darling of online lending valued at $2 billion, failed to properly handle rudimentary loan practices. The lender is Chicago-based Avant, who reportedly settled with the FTC for $3.85 million.

According to the FTC, Avant struggled to accurately determine borrower loan balances and repeatedly mismanaged payments. FTC Bureau of Consumer Protection Director Andrew Smith said that Avant’s issues were systemic. “Online lenders need to understand that loan servicing is just as important to consumers as loan marketing and origination, and we will not hesitate to hold lenders liable for unfair or deceptive servicing practices,” he said in a press release.

The FTC alleged:

“When consumers got an email or verbal confirmation from Avant that their loan was paid off, the company came back for more – sometimes months later – claiming the payoff quote was erroneous. The FTC says Avant dinged consumers for extra fees and interest and even reported to credit bureaus that loans were delinquent after consumers paid the quoted payoff amount.”

The FTC further stated:

“The lawsuit also alleges that Avant charged consumers’ credit cards or took payments from their bank accounts without permission or in amounts larger than authorized. Sometimes Avant charged duplicate payments. One unfortunate consumer’s monthly payment was debited from his account eleven times in a single day. Another person called Avant’s customer service number trying to reduce his monthly payment only to be charged his entire balance. In other instances, Avant took consumers’ payoff balance twice. One consumer was stuck with overdraft fees and angry creditors when Avant withdrew his monthly payment three times in one day.”

In a subtle dig, the FTC said that online lending could be beneficial “if 21st century financial platforms abandon misleading 20th century practices.”

Under the settlement order, Avant, LLC will be prohibited from taking unauthorized payments and from collecting payment by means of remotely created check (RCC). The company also is prohibited from misrepresenting: the methods of payment accepted for monthly payments, partial payments, payoffs, or any other purpose; the amount of payment that will be sufficient to pay off in its entirety the balance of an account; when payments will be applied or credited; or any material fact regarding payments, fees, or charges.

Indicted Loan Brokers Out On Bond, 1 Still in Custody

April 5, 2019 Four of the five loan brokers indicted in a fake business loan scam that tricked an Ohio resident out of hundreds of thousands of dollars in upfront fees, have been released on bond. Only one, a defendant by the name of Haki Toplica, remains in custody. All of the defendants have entered pleas of not guilty.

Four of the five loan brokers indicted in a fake business loan scam that tricked an Ohio resident out of hundreds of thousands of dollars in upfront fees, have been released on bond. Only one, a defendant by the name of Haki Toplica, remains in custody. All of the defendants have entered pleas of not guilty.

In addition to the victim being asked for hundreds of thousands of dollars in upfront fees to apply for phony loans, he also signed over the title of 55 vehicles to the defendants to serve as the collateral. The vehicles included a Ford Mustang, several dump trucks, several tractors, several restored classic vehicles, a Freightliner motor home, and trailers.

Toplica was arrested in December and his co-conspirators in March. All of them are New York residents. The condition of one defendant’s release was that she remain working with her present employer. deBanked determined that her most recent employment was ironically that of a business loan broker.

Class Action Lawsuit Filed Against Brendan Ross, Direct Lending Investments, and Others

April 2, 2019 A class action lawsuit has been filed in California against Direct Lending Investments, LLC (DLI), Brendan Ross, Bryce Mason, Frank Turner, Rodney Omanoff, and Quarterspot Inc. alleging breach of contract, breaches of fiduciary duty, aiding and abetting breaches of fiduciary duty, and fraudulent inducement.

A class action lawsuit has been filed in California against Direct Lending Investments, LLC (DLI), Brendan Ross, Bryce Mason, Frank Turner, Rodney Omanoff, and Quarterspot Inc. alleging breach of contract, breaches of fiduciary duty, aiding and abetting breaches of fiduciary duty, and fraudulent inducement.

The claims are drawn from a series of revelations that have come out about the online lending hedge fund, namely that the fund lost nearly 25% of its value through a failed loan to VOIP Guardian Partners I (VOIP) and an SEC complaint that alleged DLI engaged in a scheme to misrepresent performance with the help of an online lender it invested in.

Plaintiffs point out many issues with the VOIP deal but hone in on the fact that the company engaged in risky behavior by taking DLI’s funds and lending out more than 75% of them to just two companies, Najd Technologies Ltd and Telacme Ltd. deBanked previously determined these now-defunct companies were headquartered in the United Arab Emirates and Hong Kong. Documents obtained through VOIP’s bankruptcy filing indicate that both companies ceased making payments in October 2018. Despite this, DLI continued to report to investors that they were achieving very favorable monthly returns, the plaintiffs say, and no mention of VOIP’s distress was disclosed.

Bryce Mason and Frank Turner were named as defendants because they sat on DLI’s investment committee with Ross.

The plaintiffs are investment vehicles for a husband and wife that DLI last reported had a combined value of $758,000. They seek class action certification. They had only just begun investing with DLI last year.

On Monday, a judge in the SEC lawsuit ordered that DLI be placed in receivership. Bradley D. Sharp of Development Specialists, Inc. has been appointed to serve as permanent receiver for the fund’s estate.

You can download the full class action lawsuit complaint here.

Direct Lending Investments Charged With Fraud by the SEC

March 25, 2019 Update: DLI has agreed to the appointment of a receiver to marshal and preserve the assets of Direct Lending and the funds. The SEC has also published a press release on the matter.

Update: DLI has agreed to the appointment of a receiver to marshal and preserve the assets of Direct Lending and the funds. The SEC has also published a press release on the matter.

One of the biggest online lending hedge funds has been accused of fraud by the SEC. On Friday, the SEC sued Direct Lending Investments (DLI) with perpetrating a multi-year fraud that misrepresented the value of loans in a segment of its portfolio.

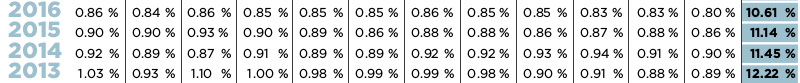

A DLI employee told the SEC that CEO Brendan Ross helped engineer loans to be valued at par when they should’ve been valued at zero. Emails between Ross and the online loan platform suggest that this was intentional, the SEC argued. The effect of this was that between 2014 and 2017, DLI overstated the valuation of one of its loan portfolio positions by approximately $53 million and misrepresented the fund’s performance by about 2-3% annually.

The SEC seeks a preliminary injunction and appointment of a permanent receiver; permanent injunctions; disgorgement with prejudgment interest, and civil penalties.

You can download the full SEC complaint here.

Below: DLI’s stated monthly returns 2013-2016

A 2017 DLI investor presentation touted “double-digit returns with no down months since inception” and a portfolio that has “exhibited little volatility.”

Analyzing Confessions of Judgment

March 4, 2019 Platzer, Swergold, Levine, Goldberg, Katz & Jaslow, LLP (“Platzer”) has built one of the leading Merchant Cash Advance practices in New York City. With years of experience handling traditional lending transactions, Platzer has expanded its representation to Merchant Cash Advance Companies (“MCA”) in all aspects of their business cycles, including Participation Agreements, Assets Utilization, Transactional related matters and litigation.

Platzer, Swergold, Levine, Goldberg, Katz & Jaslow, LLP (“Platzer”) has built one of the leading Merchant Cash Advance practices in New York City. With years of experience handling traditional lending transactions, Platzer has expanded its representation to Merchant Cash Advance Companies (“MCA”) in all aspects of their business cycles, including Participation Agreements, Assets Utilization, Transactional related matters and litigation.

In the course of representing some of its MCA clients within the State of New York, Platzer has identified a potential issue in certain counties within New York State that are denying entry of Confessions of Judgment (“COJs”), notwithstanding language that has been contractually agreed upon and explicitly sets forth that the Confession of Judgment “may be entered in any and all counties with in the State of New York”, when the defendant is a non-resident.

The following is not a legal opinion but is our preliminary analysis:

It is Platzer’s position that New York Civil Practice Law and Rules (“CPLR”) 3218(a)(1) provides that when the defendant is a “non-resident” that judgment by confession may be entered in “the county in which entry is authorized.” Further, CPLR 3218(b) allows entry of judgment by confession as to a non-resident“ with the clerk of the county designated in the affidavit.” Platzer respectfully argued to the subject county that its jurisdiction is within the scope of authorization of “all counties” in the State of New York, and that the defendant “authorized” entry of judgment in the subject County, as contemplated by CPLR 3218(a)(1), and was also designated, as one of “all counties” in the State of New York, satisfying CPLR 3218(b), yet the Confession was denied entry.

As Platzer then noted, there is case authority for the proposition that non-resident defendants may subject themselves under CPLR § 3218 to the entry of judgment by confession in multiple counties. To Platzer’s knowledge, no Court has passed on the precise language of “all counties” or similar language. In the analogous situation where the confession of judgment executed by the non-resident defendant allowed entry in multiple but not “all” counties, Courts have routinely upheld entry of the judgment, while noting that there is no authority that would prohibit such entry under CPLR § 3218. Platzer has contended that this case law supports the notion that entry of confessions of judgment with “all counties” language is proper under CPLR § 3218.

As of March 4, 2019, Platzer is actively discussing these issues with the subject counties within the State of New York and hopes that its arguments will be persuasive based upon current New York law. Platzer is aware, however, of the state and national legislative efforts to curtail the entry of confessions of judgment and, specifically, the recent legislative proposal by Governor Andrew Cuomo to restrict entry of confessions of judgment to defendants doing business in New York and in amounts over $250,000.00. Platzer expresses no opinion as to these efforts.

Contacts:

Howard M. Jaslow

hjaslow@platzerlaw.com

Morgan S. Grossman

mgrossman@platzerlaw.com

Platzer, Swergold, Levine, Goldberg, Katz & Jaslow, LLP

475 Park Avenue South, 18th Floor

New York, New York 10016

Telephone: (212) 593-3000 ext. 248

Facsimile: (212) 593-0353

1 Global Capital Issued Securities, Court Rules

February 17, 2019 1 Global Capital founder Carl Ruderman suffered a major setback in his case with the SEC earlier this month, when the Court ruled that his company’s Syndication Partner Agreements and Memorandums of Indebtedness were in fact, securities. Ruderman had filed a motion to dismiss the SEC’s claims against him personally but the Court struck it down.

1 Global Capital founder Carl Ruderman suffered a major setback in his case with the SEC earlier this month, when the Court ruled that his company’s Syndication Partner Agreements and Memorandums of Indebtedness were in fact, securities. Ruderman had filed a motion to dismiss the SEC’s claims against him personally but the Court struck it down.

1 Global sold its notes to more than 3,400 investors in at least 25 states, who collectively invested at least $287 million. The company declared bankruptcy last year amid parallel criminal and civil investigations that hampered its ability to raise capital. The SEC filed suit soon after but no criminal charges have been brought to date.

In the ensuing legal discovery, it was revealed that the company funded the largest merchant cash advance in history, a collective $40 million funded over several transactions to an auto dealership group in California. Those dealerships closed not longer after 1 Global Capital’s bankruptcy. Those closures have sparked a lawsuit of its own and with it the revelation that several of 1 Global Capital’s competitors had also funneled millions into the dealerships.

The Court’s ruling in the motion to dismiss whereby the investments were deemed securities can be downloaded here.