Articles by Cheryl Winokur Munk

Commission Chargebacks: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

August 10, 2015 Imagine you’re a 20-something-year-old broker who’s just, in good faith, referred a merchant to a funder. You walk away with a few thousand dollars in your pocket, and you promptly spend it on rent and a celebratory steak dinner. Then all of a sudden…BAM! Just like that the merchant goes belly up and the funder’s knocking on your door to clawback your hard-earned commission money, which, of course, you’ve already spent.

Imagine you’re a 20-something-year-old broker who’s just, in good faith, referred a merchant to a funder. You walk away with a few thousand dollars in your pocket, and you promptly spend it on rent and a celebratory steak dinner. Then all of a sudden…BAM! Just like that the merchant goes belly up and the funder’s knocking on your door to clawback your hard-earned commission money, which, of course, you’ve already spent.

For many brokers, it’s a familiar-sounding story—with an ending they’d like to rewrite. Their thinking goes like this: underwriters, not brokers, are the ones who are supposed to dig into a company’s finances before approving a deal. Underwriters, not brokers, are the ones who make the financial decisions about whether or not a deal can go forward. Therefore, underwriters, not brokers, should be responsible when deals implode.

“There are a lot of people who think there should not be commission clawbacks—that they’re unfair,” says Archie Bengzon, who runs the New York sales office for Miami-based Rapid Capital Funding, a direct funder. Bengzon was previously the president of Merchant Cash Network, an ISO in New York.

While there’s a fair amount of closed-door grousing by brokers, most funders are standing their ground—with only a select few companies kicking these controversial policies to the curb. More commonly, funders claim clawbacks, despite being hated by brokers, are a necessary evil. These funders say that without them, they’d stand to lose too much on bad deals and that they need a way to protect themselves from rogue brokers.

“There is a group of people out there who are trying to game the system,” says industry attorney Paul Rianda, who heads a law firm in Irvine, California.

The Case for Scrapping Clawbacks

Brokers in favor of changing the status quo understand the need to prevent bad apples from smelling up the entire industry. But even so they believe that chargebacks are patently unfair to the honest majority of brokers who often make just enough to scrape by. In most cases, the brokers are typically young—18-to-26-year-olds trying to make money and learn the industry. They don’t have the financial resources that the funders do and the onus shouldn’t be on them if the deal they brought in—with good intentions—goes bust in a short time, according to the owner of a top-tier ISO/Hybrid in Staten Island, New York, who requested his name not be used.

This is especially true in cases where the underwriter took risks they shouldn’t have or decided to fund merchants in cases where they shouldn’t have. “It’s the underwriter’s job to protect the money that their company is lending out,” he says. “[Chargebacks] shouldn’t be going on in this industry.”

One solution might be for more ISOs to stand up to funders and refuse to send them future deals. That’s exactly what the Staten Island executive did a few years ago when a funder he repeatedly worked with tried to claw back his commission on a particular deal. He made a big stink and told them he’d never send them business again. It was enough of a threat to convince the funder to back off. “If more ISOs start saying that…then the funders will start sweating and change their contracts. Because it really isn’t fair,” he says.

For some brokers, however, taking such a strong position with funders is a risky strategy in a cottage industry where all the major players know each other and there’s no shortage of hungry young brokers willing to do business. So while these brokers don’t like losing money, they aren’t necessarily loudly crying foul either.

Matthew Ross, managing member of Go Ahead Funding, a broker and funder in Basalt, Colorado, has been in the business for nine years. He’s only had one commission clawed back once in this time period—it was a commission for $1,500 on a $25,000 deal that went sour within a month, he recalls. He was upset at the time and felt the underwriter should have done more to vet the merchant who went belly up. “Why didn’t the underwriters catch this?” he remembers asking at the time.

Matthew Ross, managing member of Go Ahead Funding, a broker and funder in Basalt, Colorado, has been in the business for nine years. He’s only had one commission clawed back once in this time period—it was a commission for $1,500 on a $25,000 deal that went sour within a month, he recalls. He was upset at the time and felt the underwriter should have done more to vet the merchant who went belly up. “Why didn’t the underwriters catch this?” he remembers asking at the time.

Nonetheless, Ross was a lot calmer than some brokers might have been under the circumstances. For instance, he says he never threatened to stop sending the funder business as many brokers might have done. “I don’t necessary like it, but I understand it. I’m not going to fight it,” he says.

Some brokers are making their displeasure with the practice known by declining to sign contracts that contain clawback clauses. Nathan Abadi, founder and president of Excel Capital Management, a New York-based funder and ISO, says he either refuses to do business outright or he comes to a verbal agreement with a funder that he’ll wait two weeks for payment to make sure the deal has legs. “I meet them in the middle,” he says.

The reason he likes this approach is that it’s more palpable for brokers to lose paper commissions versus actual money that they’ve already been given and possibly spent. Otherwise, as a business owner working with numerous agents, it’s bad for business. “It causes an internal conflict because now you have to penalize the person who’s working for you,” Abadi says.

The Flip Side of the Chargeback Coin

Meanwhile, there’s a whole other camp within alternative funding—including some brokers—who feel chargebacks are important as a fraud-deterrent. Given the fact that the industry is still largely unregulated, many believe that funders need some type of fire retardant to prevent being burned by unscrupulous brokers.

“We think that they serve an important role,” says Stephen Sheinbaum, founder of Merchant Cash and Capital, a New York-based funder. “Most of our stronger referral partners do not object to it. It’s a way of aligning our interests with the sales force.”

About 60 percent of the company’s funding business comes from third-parties including ISOs; its direct sales force accounts for the other 40 percent.

Even some brokers concede that clawbacks can serve a valuable purpose. Sure, it’s aggravating to lose money, but they feel that without clawbacks the industry would be even more of a free-for-all than it already is.

“I can see both sides,” says Bengzon, the funder and broker. Wearing his broker hat, Bengzon has felt the sting of losing a commission once or twice in the 100 or so deals he’s done. But he still understands why funders—who take a big monetary hit when deals go sour—would want to protect themselves and require brokers to have some skin in the game.

“If we’re going to reap the rewards of a nice commission, we should also understand that it can still be taken away if a deal goes bad,” he says.

When he sends leads to funders, Ross of Go Ahead Funding says he does his best to make sure he’s sending only high quality merchants. He tries to vet them upfront—to the limited extent he can—in order to avoid problems later on. Clawback provisions serve as “an incentive for [brokers] to keep their eyes open,” he says.

Know What You’re Signing

About 80 percent of the agreements that come across the desk of Rianda, the industry attorney, have a 30-day clawback provision. But he’s seen some agreements that have longer time frames—60, 90 or even 120 days. Those types of contracts aren’t as common, but they’re out there.

It’s important for brokers to carefully read the fine print of a contract before signing on the dotted line. “It sounds obvious, but a lot of people don’t do that,” says Bengzon.

The shorter the clawback time frame, the less brokers tend to balk. “People don’t want to be paid on a deal and three months later they lose that commission, which they’ve already spent,” he says.

Bengzon believes a clawback that extends any more than a month is excessive. “I would never sign something greater than 30 days,” he says.

According to Sheinbaum of Merchant Cash and Capital, 30 days is an appropriate time frame to help weed out fraud without putting unnecessary burden on brokers who are sending legitimate business. “The purpose of the provision is to try and stop people from committing fraud at the outset,” he says.

According to Sheinbaum of Merchant Cash and Capital, 30 days is an appropriate time frame to help weed out fraud without putting unnecessary burden on brokers who are sending legitimate business. “The purpose of the provision is to try and stop people from committing fraud at the outset,” he says.

David Sederholt, executive vice president and chief operating officer at Strategic Funding Source Inc. in New York, says clawback provisions in the contracts Strategic uses range from 30 to 45 days depending on the contract. He says he understands brokers don’t like them, but that it’s nonetheless important to have the provision in order to protect the funders. “There’s got to be some partnership involved here,” he says.

Clawbacks Not A Free-For-All

Many funders recognize that there’s a fine line between protecting their business and cutting off potential revenue sources.

“You start clawing back commissions on every default, a broker will stop sending business,” says Ross of Go Ahead Funding.

Sheinbaum of Merchant Cash and Capital notes that clawbacks aren’t used as often as some brokers might think. He says out of 800 deals in a 30- or 31-day period, his company enforces its clawback policy only a handful of times each month.

He also points out that while the clawback policy is on the books, Merchant Cash and Capital looks at each situation individually. If it’s clear that the broker tried to defraud the funder, that’s one thing, he says. But, if for instance, a merchant has a heart attack and dies 20 days into a deal and can’t pay back the funds, Merchant Cash and Capital wouldn’t try to clawback the broker’s commission in that situation, he says.

Strategic Funding has only clawed back commissions once or twice in the past nine years, says Sederholt, the EVP.

The company works with a variety of brokers. Some have less than a 1 percent default rate and others have 12 percent to 14 percent default rates. As extra protection with brokers who have bad track records, Strategic Funding either declines to work with them at times, or has in place a stronger underwriting procedure with these deals.

Being more careful upfront is a better tactic than trying to go after commissions, which is extremely hard, Sederholt says.

Changing the Modus Operandi

While it’s not the industry norm, there are a few funders who have stopped using clawbacks, or are considering doing so, given all the headaches they can cause. Isaac D. Stern, chief executive of Yellowstone Capital LLC, a New York-based funder, says his company no longer tries to clawback commissions when deals go bust. The few times they tried to clawback commissions several years back, the brokers they went after were upset and threatened not to do business with them anymore. Yellowstone decided this approach was bad for business and that it would be more prudent to try something else.

“There’s too much competition, and if we were going to do clawbacks it would decimate our business,” he says. “It’s the broker’s job to bring in the deals. It’s our job to underwrite it. If something goes wrong on the deal, that’s on us. It’s not the broker’s fault.”

As protection, the contracts Yellowstone uses with brokers contain a provision allowing it to seek damages when fraud’s alleged. But in cases where brokers send what seems to be a legitimate deal that goes bad for something other than fraud, Yellowstone turns the other cheek. Yellowstone can afford to eat the $5,000 or $6,000 commission to ensure ongoing—and hopefully more positive leads—or so the thinking goes, according to Stern.

Overtime—if peer pressure continues to mount—it’s possible that more even more funders will decide chargebacks just aren’t worth the trouble. “I think the reason why some funders are moving away from [clawbacks] is because people are afraid of losing volume. Once one funder acquiesces, others will follow suit,” says Sheinbaum of Merchant Cash and Capital.

Investing in the Industry: Break Out of Your Bubble

June 29, 2015 Even if you’re already working in alternative lending and know a lot about your particular area, the industry is growing by leaps and bounds and you might be feeling a little overwhelmed by the multitude of investment opportunities. Amid all the options, finding the right place to invest your money can feel as challenging as picking out the proverbial needle in a haystack.

Even if you’re already working in alternative lending and know a lot about your particular area, the industry is growing by leaps and bounds and you might be feeling a little overwhelmed by the multitude of investment opportunities. Amid all the options, finding the right place to invest your money can feel as challenging as picking out the proverbial needle in a haystack.

“Most people don’t know everything that’s out there. There are huge opportunities,” says Peter Renton, an investor and analyst who founded Lend Academy LLC of Denver, Colorado, a popular resource for the online lending industry.

Indeed, there are a growing number of online alternative lending sites that theoretically allow a person to invest in all shapes and sizes of loans. There are sites like Lending Club and Prosper that allow smaller investors to tap into the burgeoning P2P market. There are also a plethora of platforms that cater only to wealthier, more sophisticated investors in a host of areas like small business, real estate, student loans and consumer loans.

Even though there is a surplus of options, prudent investing is not quite as simple as depositing ample funds in an account and clicking the “go” button. Before you get started, you need to carefully consider factors such as your own finances and risk tolerance. You should also have a good handle on the specifics about the online platform—how it works, its history and track record, the types of investments it offers, the platform’s management team, technology and your ability to diversify based on available investment opportunities.

One of the first things you’ll have to think about as a potential investor is whether you have the financial wherewithal to be considered accredited by the SEC. If the answer’s yes, you’ll have a lot more choices of online marketplaces to choose from as well as types of investments. Basically, to meet the SEC’s threshold, you’ll need to have earned income that exceeded $200,000 (or $300,000 together with a spouse) in each of the prior two years, and reasonably expect to earn the same for the current year. Alternatively, you need to have a net worth over $1 million, either alone or together with a spouse (excluding the value of your home). (Check out the SEC’s website for more detailed info.)

If you don’t fit the definition of accredited investor, it’ll be more difficult for you to find out about all the investment possibilities that are on the market today. That’s because the platforms that cater to accredited investors aren’t allowed by SEC rules to solicit, so many online marketplaces are hesitant to say much of anything for fear their words will be misconstrued by regulators as an attempt to drum up new business. With limited exceptions, you won’t be able to get more than very basic information from and about these platforms’ unless you are accredited.

If you don’t fit the definition of accredited investor, it’ll be more difficult for you to find out about all the investment possibilities that are on the market today. That’s because the platforms that cater to accredited investors aren’t allowed by SEC rules to solicit, so many online marketplaces are hesitant to say much of anything for fear their words will be misconstrued by regulators as an attempt to drum up new business. With limited exceptions, you won’t be able to get more than very basic information from and about these platforms’ unless you are accredited.

But smaller investors do have options. Two San Francisco-based online lending platforms, Lending Club and Prosper, cater to individual investors, and you can still make a pretty penny plunking down money with these venues. You’ll also find a wealth of information about investing with them by perusing their websites as well as by reading the blog posts of media-savvy financiers.

“Right now, Lending Club and Prosper provide a great entry point for people who want to get involved in investing in alternative lending,” says Renton of Lend Academy.

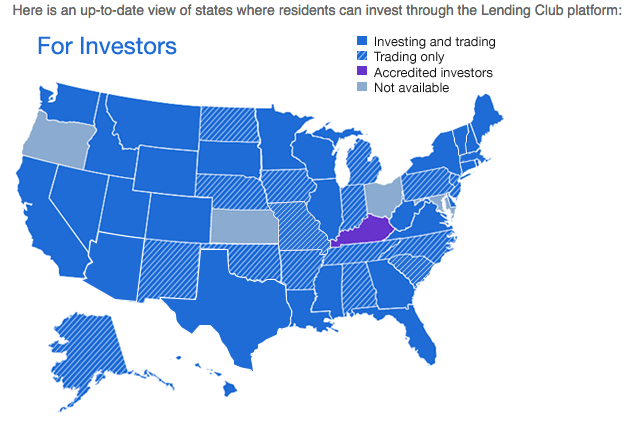

The caveat is that these platforms aren’t yet open to investors in every state, so if yours isn’t on the list you’re out of luck for now. However, with each marketplace you’ve got more than a 50 percent chance your state is on the approved list, so it’s worth digging deeper.

Assuming you meet their respective suitability requirements, you can choose to invest on one platform or both. To be sure, they are alike in many ways. Both allow you to invest with as little as $25 and fund one loan, however they recommend you buy at least 100 loans to be properly diversified, which you can do for as little as $2,500. You can manually choose which loans to buy, or enter your investment criteria so loan picking is automated. You can also invest retirement money in an IRA through Lending Club or Prosper.

There’s no fee to get started investing on either platform. For Lending Club, investors pay a service fee equal to 1 percent of the amount of payments received within 15 days of the payment due date. Prosper charges investors 1% per year on the outstanding balance of the loan. As the loan gets smaller, the servicing fee, which is charged monthly, gets smaller too.

To invest in Lending Club, in most cases you’ll need either $70,000 in income and a net worth of at least $70,000, or a net worth of at least $250,000. There may be other financial suitability requirements that vary slightly depending on the state you live in. For Prosper, individual investors must be United States residents who are 18 years of age or older and have a valid Social Security number.

At any given time, Lending Club has more than 1,000 loans visible on the platform and new ones get added every day, according to Scott Sanborn, chief operating officer and chief marketing officer. Prosper, meanwhile, on average has more than 200 loans for people to invest in, says Ron Suber, president.

Returns tend to be favorable compared with other fixed income investments—a major reason investing in online loans is becoming more desirable. Of course, actual returns will depend on what loans you invest in and the level of risk you take—typically the more risk you take on, the greater your potential return will be. At Lending Club, for instance, Grade-A loans have an adjusted net annualized return of 4.89%, compared with 9.11% for Grade-E loans, according to the company’s website.

Returns tend to be favorable compared with other fixed income investments—a major reason investing in online loans is becoming more desirable. Of course, actual returns will depend on what loans you invest in and the level of risk you take—typically the more risk you take on, the greater your potential return will be. At Lending Club, for instance, Grade-A loans have an adjusted net annualized return of 4.89%, compared with 9.11% for Grade-E loans, according to the company’s website.

To encourage more people to start investing, some savvy investors have started to self-publish online the quarterly returns they accumulate through the Lending Club and Prosper platforms. Renton, of Lend Academy, reported a balance of $476,769 on Dec. 31, 2014 and a real-world return for the trailing 12 months of 11.11 percent. Another well-known P2P investor and blogger, Simon Cunningham—the founder of LendingMemo Media in Seattle—reported a 12-month trailing return of 12.0 percent over the same time period, with a published account value of $41,496. Both investors say they expect returns to drop back somewhat over time, however, as the online marketplaces continue to lower interest rates to attract more borrowers.

Of course, if you’re an accredited investor, you will have access to even more online marketplaces. For instance, there’s SoFi of San Francisco for student loans, Realty Mogul of Los Angeles for real estate loans and Upstart of Palo Alto, California, that focuses on loans to people with thin or no credit history. The list of possibilities goes on and on.

Generally speaking, the more money you have to invest, the more options you have. “In this country today, you’ve got well over a hundred options if you’re willing to put seven figures in,” Renton says.

The minimums at venues that focus on accredited investors tend to be more than you’d find at Lending Club or Prosper. At SoFi, accredited investors need at least $10,000 to begin investing in the company’s unsecured corporate debt. SoFi’s been in the lending business for several years now and currently focuses on student loans, mortgages, personal loans and MBA loans. Investors, however, can’t currently invest in these loans, says Christina Kramlich, co-head of marketplace investments and investor relations at SoFi. The company plans to eventually offer investment opportunities in the areas of mortgages and personal loans, she says.

At Funding Circle USA in San Francisco, accredited investors can buy into a limited partnership fund for at least $250,000. Or they can buy pieces of small business loans for a minimum of $1,000 each, though the recommended minimum is $50,000, explains Albert Periu, head of capital markets. There may also be upper limits on your investment, based on your financials. If you’re part of the pick-and-choose marketplace, you’ll pay an annual servicing fee of 1%. With the fund, you’ll also pay an administration fee of 1%. Trailing 12-month net returns for investors are north of 10%, Periu says.

At Funding Circle USA in San Francisco, accredited investors can buy into a limited partnership fund for at least $250,000. Or they can buy pieces of small business loans for a minimum of $1,000 each, though the recommended minimum is $50,000, explains Albert Periu, head of capital markets. There may also be upper limits on your investment, based on your financials. If you’re part of the pick-and-choose marketplace, you’ll pay an annual servicing fee of 1%. With the fund, you’ll also pay an administration fee of 1%. Trailing 12-month net returns for investors are north of 10%, Periu says.

Because it’s still so new, it can be hard for investors to know how to compare marketplaces. For starters, consider the platform’s historical performance. There are a lot of new marketplaces popping up, but it takes time to develop a proven track record. This isn’t to say you shouldn’t dabble with the newer platforms, but if you do, you’ll want above-average returns to balance out the higher risk, says Sanborn of Lending Club. “About three years in, we started to build a track record. At five years in, it was very solid,” he says. “You need time to see how a basic batch of loans is going to perform.”

Before investing, you’ll want to get a sense of how committed senior management is to the company and try and get a sense of whether the company seems to have enough capital for the business to run well. Try to find out about the cash position of the company, how the loans are going to be serviced, what entity is doing the underwriting and how and where your cash will be held.

“It’s not just assessing the risk of the asset and the investment, it’s assessing the risk of the enterprise that is making it available to you,” Sanborn says.

It’s also important to ask questions about the loans themselves. Where do they come from and is the volume sustainable? Ideally, a platform should offer a variety of loans so investors can properly diversify, or you might need to consider investing with multiple platforms to achieve your desired balance.

Before you get started, you’ll also want to ask about the company’s compliance procedures and controls and how you can recover your money if you no longer want to invest. Data security is another area to explore. Not every company is as protective of customer data as perhaps they should be.

Before you get started, you’ll also want to ask about the company’s compliance procedures and controls and how you can recover your money if you no longer want to invest. Data security is another area to explore. Not every company is as protective of customer data as perhaps they should be.

When you’re asking all these questions, try to get a sense of how receptive the platform is to the feelers you’re putting out. Investors should only work with companies that are willing to be open about how they are investing your money, their historical returns and other important data. “I can’t stress transparency enough,” says Periu of Funding Circle.

The technology the platform uses is another key element. Is the technology easy to use, or does the platform create stumbling blocks for investors? Are there ways to automate lending, or do you have to log on every day and manually invest in loans?

Suber of Prosper says investors should also consider whether platforms work with a back-up servicer in case there’s a disruption and whether they run regular tests to make sure everything works as expected. “It’s just like a backup generator and you have to test it every once in a while and make sure it goes on.”

Certainly it pays to do your homework before you invest your hard-earned cash with an online platform. Ask around, attend industry conferences and absorb all you can from publicly available data. The good news is that there will probably be even more information for you to tap into as the industry continues to grow.

“Two years ago [marketplace lending] was very esoteric. A year ago it was still esoteric,” says Funding Circle’s Periu. Now, more and more investors are hearing about marketplace lending and want to make it part of their broader fixed income bucket. Even so, more has to happen for it to become a mainstream investment. “Awareness and education need to continue,” he says.

Once more people understand the extent of what’s out there, Suber of Prosper expects investing in online marketplaces will take off even more than it already has. “A lot of people still don’t know this as an investment opportunity,” he says.

Good Recordkeeping Plays Important Role in Funding Success

April 17, 2015CPA Yoel Wagschal recently started working with a syndicator who relied on Excel spreadsheets to track all his deals. The syndicator thought he had everything in tip-top shape, but it turns out that his system was hard for an outsider to understand and the data didn’t reconcile with his bank statements.

Wagschal, who heads an accounting firm in Monroe, New York, comes across this problem frequently these days. It’s been exacerbated by the exponential growth of the alternative funding industry in recent years. There are a sizeable number of alternative funders that started out small and have grown by leaps and bounds, yet they are still using rudimentary systems to keep track of their business dealings. In most cases, funders want to do the right thing, but they don’t always know how or the extent of what’s involved. Unknowingly these funders may be setting themselves up for financial or legal troubles.

“Sooner rather than later you are going to find yourself swimming in the Atlantic Ocean without any plan on how to get out of there,” Wagschal says.

“Sooner rather than later you are going to find yourself swimming in the Atlantic Ocean without any plan on how to get out of there,” Wagschal says.

Although newbie funders may be able to get by with simple tools and minimal staff, more sophisticated efforts are required once they are doing multiple transactions a month. It’s one thing when you are tracking a few daily deals on a spreadsheet. It’s quite another when you’re trying to keep track of all the moving parts for hundreds of deals.

What’s more, there’s a lot of slicing and dicing of data that goes into properly understanding your existing business and growth possibilities. If you don’t use the right tools to help you keep precise records, it’s nearly impossible to understand the fundamentals of your business in order to grow. Excel, while a useful tool, has its limits, and funders who rely exclusively on spreadsheets don’t get the benefits of other more sophisticated options that have become available to them in the past few years. Manually entering data also increases the possibility of human error, which can lead to thousands upon thousands of lost revenue for a funder’s business.

The Pitfalls of Not Keeping Good Data

Keeping good data is especially important to funders who want to take on additional investors or who are considering a sale at some point. Kim Anderson, chief executive of Longitude Partners Inc., a strategic advisory firm in Tampa, Florida, works with a number of funders that are looking to facilitate additional growth by bringing on outside investors. Many of these companies find themselves scrambling because they don’t readily have access to the kind of information potential investors want.

Not keeping good books can also inhibit a funder’s ability to expand into additional markets. Say a funder wants to introduce a new product or migrate a product offering to a different vertical. Companies that don’t analyze their data effectively may have a hard time understanding what part of their existing portfolio would be the most appropriate or profitable segment to introduce the product to, Anderson says.

Potentially impeding growth is bad enough, but funders that don’t keep proper books can also find themselves embroiled in legal or tax troubles. Some MCA providers, for instance, have faced stiff penalties for treating transactions as loans on their books instead of the purchase and sale of future income.

“If they are showing the revenue recognition in the exact same way that loan industry companies are doing, then they are setting themselves up to be judged in the same way that a loan company would,” says Christina Joy Tharp, a staff accountant in Wagschal’s office. If you’re using the same accounting methods as lenders, you could be deemed a predatory lender by multiple enforcement agencies, even if that’s not your intent, she says.

The strength of your business can also be significantly impacted by how you classify performing and nonperforming loans or receivables. “There are thousands of pages of rules on how banks have to classify performing and non-performing loans. None of that exists for this industry, which is completely unregulated,” says Alex Gemici, managing director and head of M&A at World Business Lenders, an alternative lending company in Manhattan.

As a result, funders don’t have a universal way of keeping their books. Many funders believe that as long as they are collecting sporadic payments, a loan or receivable should be classified as performing. Gemici strongly disagrees, saying this approach sets up a funder for potential failure given that the default rate for loans/receivables is about one in five. “It’s one thing to show on your books that loans or receivables are performing, it’s another when you run out of cash,” Gemici says.

Choosing an Outside Provider

Recognizing that Excel spreadsheets can only carry a funder so far and that out-of-the-box software probably won’t be a complete solution for alternative funders, a small number of companies have stepped up to provide customized solutions for the industry. MCA funders—where the perceived need is greatest—are a particular focus for these providers.

Benchmark Merchant Solutions, a processor in Amherst, New York, is one such company honing in on the MCA funder space. In 2014 the company launched MCA Track, software that’s designed to help MCA funders with their recordkeeping needs. It also helps them keep track of their income for tax purposes.

Benchmark Merchant Solutions, a processor in Amherst, New York, is one such company honing in on the MCA funder space. In 2014 the company launched MCA Track, software that’s designed to help MCA funders with their recordkeeping needs. It also helps them keep track of their income for tax purposes.

Among other things, MCA Track allows funders to view their performance at a glance. It shows them, for example, how merchants are performing, how the funds are allocated according to syndicator, the status of a deal, open cash advances, closed cash advances and defaulted cash advances. Funders can also get profitability data and other types of big picture information about their business as well. The software costs about $2,000 a month depending on the user’s size.

Benny Silberstein, chief operating officer of Benchmark, says the software was created because the processing company found that funders were often asking Benchmark to get data for them, especially when there were discrepancies. It can be real headache for funders to wade through inconsistencies with merchants, syndicators and ISOs, Silberstein says. “I can’t begin to tell you how many times funders asked us for a list of all the payments they’d received.”

PSC of Port Washington, New York, is another company trying to help MCA funders keep better records and manage their business more effectively. For a monthly membership fee, the company offers a front-end to back-end relationship management solution that allows funders to track all their contacts, documents, deals and commissions. Daily reports provide detailed data and summary information about an MCA’s funding business. The data includes the actual advance amount, the right to receive amount, the factor rate, processing fees, daily debits and credits, commissions paid to outside brokers or their own people, other management fees, ACH fees, wiring fees, payments, missing payments, collections information and participation with other syndicates.

The product has been on the market for about two years and the monthly fee varies according to a funder’s size, says Tom Nix, director of sales for PSC. He declined to be more specific about cost.

“The companies that are small and just starting out—if they are just doing a few transactions a month—they could probably get by using a spreadsheet. But that’s only feasible if you have a few transactions that you’re doing per month. Once you’re growing, when you get up to 10, 20, 30, 100 deals, the management of data becomes truly uncontrollable,” says Nix, who has seen a number of funders struggling to stay afloat or exit the business entirely because of their inability to keep good records.

“If you don’t have the right information and understand it, you’re going to give money to someone and you won’t [necessarily] get it back,” Nix says.

It’s possible for funders to set up their own infrastructure, but it can be costly and some feel it detracts from their ability to generate new business. That’s why Anthony Mannino, president of Nulook Capital in Massapequa, New York, chose to work with PSC. He researched the idea of doing all the back office and data collection on his own, but he decided not to reinvent the wheel since it would have meant hiring additional staff and would divert the company’s attention away from its primary focus—bringing in new business.

“A service provider like PSC gives us the ability to grow our company controlled and in a much quicker manner than we ever could than if we had to build our back end on our own,” Mannino says. “It takes most of the responsibility off of my company so we are able to focus on just growing the business and growing the sales.”

CloudMyBiz Inc. in Los Angeles is another company trying to service the alternative funder market, providing customized CRM systems for both lenders and MCA providers.

The CloudMyBiz system relies on a platform called Salesforce and is customized to the funding industry. It helps funders with the various facets of origination, underwriting and loan servicing. It helps them generate and track leads, automate funding workflow, understand and manage their deal pipeline and daily funding activities, collect and schedule recurring ACH payments and track syndication partners.

You could buy the Salesforce software and use it out of the box, but it provides only the basic functionality that funders need to run their business properly, says Henry Abenaim, principal consultant at CloudMyBiz. That’s where CloudMyBiz comes in by customizing the software for a funder’s specific business requirements. The fee varies widely, depending on the funder’s specifications, he says, declining to be more specific.

About two and a half years ago, Creative Vision Studio LLC in Long Beach, Calif., which had focused on the merchant credit card processing industry for more than a decade, also started offering a CRM system to MCA providers. The software is called Bankcard Pros CRM and customers can use it for merchant credit card processing, MCA or both. The software automates the data entry, underwriting, approval, funding and payback process from start to finish, says Robert Hendrix, the company’s chief executive. Funders also have access to 17 different management reports so they can track the performance and profitability of their entire portfolio per month.

The company charges an upfront fee of $4,000 to $5,000 to use the software, which is customized to a particular client’s business. There’s a $399 monthly fee after that. While it may seem costly to some funders, Hendrix says the software pays for itself within a month because of the efficiencies created. Importantly, the software eliminates the possibility of costly human mistakes that can occur in manually updating daily payments on a spreadsheet. “One little mistake can cost funders $2,000 to $3,000, even up to $10,000. They can be very costly mistakes,” he says.

It is, of course, possible for funders to keep good books and records using homegrown systems and personnel, and funders need to carefully weigh their options, taking into account that doing it right will probably require a meaningful investment in infrastructure and personnel. Whether they do it alone or hire an outside vendor, the important thing for funders is to collect the data and be able to evaluate it and display it in a way that makes sense to them, their customers, tax preparers, potential investors and others who need access.

Funders also need to remember that being successful in the business over the long term requires them to do more than simply capture accurate data. Beyond that, funders need to be able to manipulate the information in a way that helps them understand the nuts and bolts of their specific business, says Anderson of Longitude Partners.

“They may be able to produce enough financial information to complete an accurate tax return, but when it comes to understanding their operating metrics, they may not have collected or evaluated all of the right information to answer questions about what really drives the growth or sustainable profitability of the business,” he says.