The Industry’s Bad Paper

Sometimes deals go bad. But what happens next?

Sometimes deals go bad. But what happens next?

I just finished reading, Bad Paper: Chasing Debt From Wall Street to the Underworld on a recommendation from a friend. In it, author Jake Halpern walks readers through the shadowy world of consumer debt collection. It was eye-opening to say the least.

Halpern’s research uncovered that consumer debts with seemingly no original paperwork is sold, resold, and resold again to companies that the debtor never heard of and would not recognize. A debt’s record amounted to some fields on a spreadsheet where the information is not always correct and might even have been collected already by someone else.

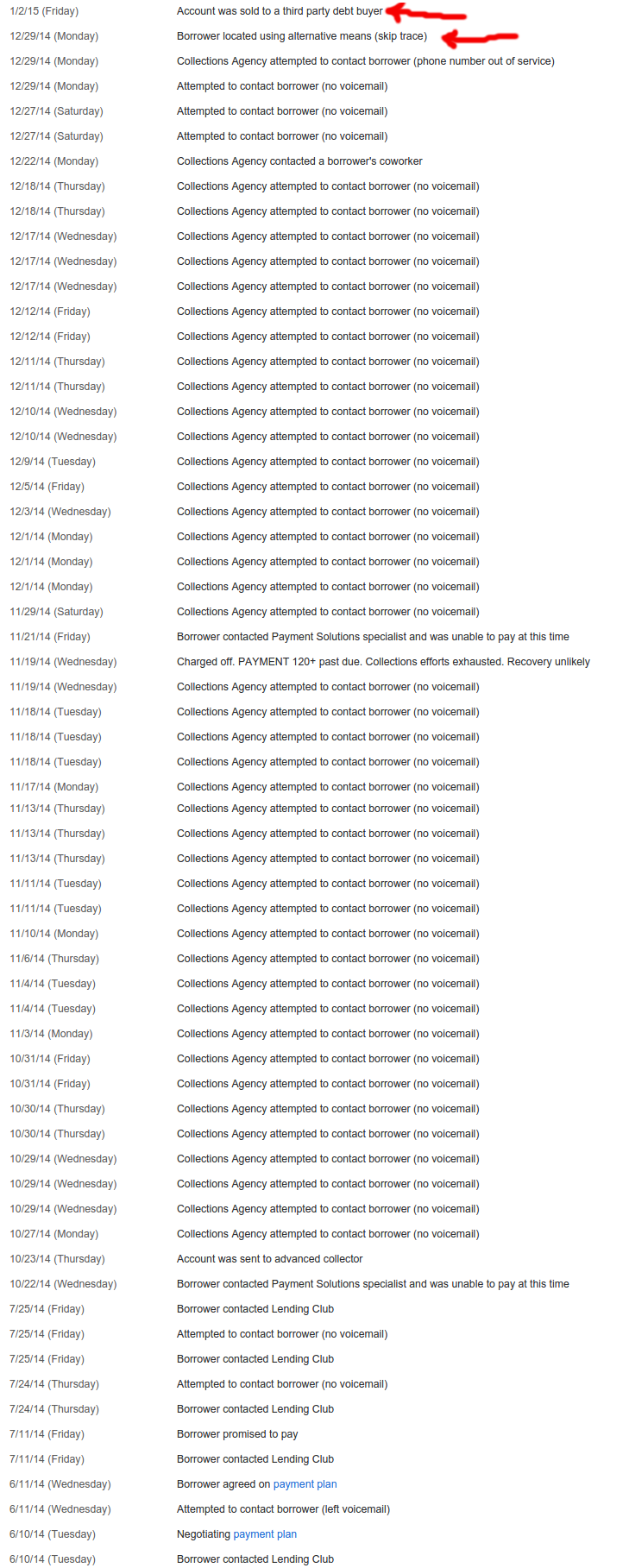

One has to wonder whose hands a Lending Club loan I participated in are in now. It was a $25,000 loan to a nurse. The notes below are from the real collections log provided by Lending Club. After making just 3 full payments on their 3-year loan, this 700 credit borrower went from negotiating a payment plan to off the grid. They called a co-worker, skip traced them, and finally gave up and sold her debt to a third party.

One has to wonder whose hands a Lending Club loan I participated in are in now. It was a $25,000 loan to a nurse. The notes below are from the real collections log provided by Lending Club. After making just 3 full payments on their 3-year loan, this 700 credit borrower went from negotiating a payment plan to off the grid. They called a co-worker, skip traced them, and finally gave up and sold her debt to a third party.

I’ve found that a lot of my defaulted loans thus far have gone bad in the first few months, a pattern that looked more like fraud than borrower hardship. It actually prompted me to call Lending Club and speak to a representative about it, who explained that they’re doing all they can to prevent fraud.

They were pretty relentless on this particular file, a nurse that was making $60,000 a year sounded like a winner. They had virtually no debt but the loan was supposedly used to consolidate outstanding debt into one monthly payment at the rate of 9.67%. The story didn’t exactly add up but since I don’t actually get to talk to the borrowers or look at their paperwork, I’m essentially just playing a numbers game.

That debt has been sold off and I as a note holder do not appear to be entitled to any money on the sale of it, not even pennies on the dollar. Bummer.

Because of platforms like Lending Club, I wasn’t the only one to lose out. 277 other retail investors who I don’t know and have never met participated in it with me. We’re all playing the numbers and we lost on this one.

With 1907 notes acquired on the platform so far, I’m not emotionally invested in any of them. How can I be? I have no idea who the borrowers are. I don’t even know their names! All I can do is diversify and make decisions based off of statistical analysis. If the borrower stops paying, go after them hard whoever they are!

Meanwhile in commercial transaction land

When it comes to merchant cash advance and business lending, the collection rules are different but so are the relationships. Even with strong advancements in automation, phone interviews remain an integral part of the underwriting process. A risk analyst typically calls the business owner, their landlord, and even several of their suppliers. Large dollar amount deals may even be presented to an entire risk committee for approval.

Suffice to say, pesky things like signed contracts do not usually prove elusive when a collector in this world gets their hands on it. Many commercial funding providers even record phone calls with the business owners where they get an additional verbal confirmation to the terms and conditions of the arrangement.

The collections process usually begins with the sales person or sales office that negotiated the terms with the business. Back when was I was an account rep, my commissions were paid in two pieces, upfront and a residual. That meant almost half my pay on a deal was tied to its performance. If a deal started to fall apart or defaulted, I had a personal stake in restoring the business to good standing.

The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act does not cover commercial transactions. And in the case of traditional merchant cash advances, there is likely no debt at all in a default, but rather a possible case of stolen receivables.

In the event where a deal I brokered was suspected of diverting receivables, I’d be the first one to know about it and the first person tasked with fixing it. That meant calls to the business, their home phones, their cell phones, and when necessary their landlord. If none worked, then their suppliers. The first goal was to determine if the business was still operating and in the vast majority of cases where defaults happened, they were.

Hardship was sometimes cited as a reason for breaching the agreement but not always. With a chunk of my paycheck on the line, I had to talk them back into good standing and unlike debt collectors, I didn’t have the ability to renegotiate the terms, lower a payment or cut them slack. It was back to the way it was or nothing.

It escalates

Some returned to good standing and others played hardball. The deal’s original underwriter might then involve themselves and if they failed, then on it went to the internal funder’s portfolio management/collections team.

This is why the situation here on out is different: Imagine a doctor sells you the accounts receivable of all his patients for a discounted price. The doctor gets cash upfront and the buyer will hopefully collect the full value of the accounts receivable to earn a profit.

Now imagine the doctor accepts your cash upfront and then also collects the accounts receivable from the patients and shuts you out. In traditional merchant cash advances, collectors aren’t going after debt, but rather acquired property that is rightfully theirs. The business has shut them out of receivables they purchased.

If internal collection efforts fail, they can attempt to freeze various receivables the business might have. Merchant processing proceeds are usually the first stop. If the business accepts credit cards, the merchant processor can be instructed to freeze all or a percentage of the revenues without a court order. This is easier said than done but it does work and there are even a few third party collection firms that specialize in this.

And if that doesn’t work? Well, thousands of lawsuits have been filed against businesses for breaching these commercial transactions. The business owners themselves can potentially be culpable and liable depending on the agreement and the nature of the breach.

And if that doesn’t work? Well, thousands of lawsuits have been filed against businesses for breaching these commercial transactions. The business owners themselves can potentially be culpable and liable depending on the agreement and the nature of the breach.

Some business owners are shocked to learn that a deal they made over the phone with people they never met will actually track them down and sue them. Unlike consumer debts which might only be a few hundred dollars, commercial transactions are typically tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of dollars. They will definitely pursue it.

On the largest default I ever presided over as an underwriter, the business owner said something to the effect of, “I stole your money. Let’s see how good you are at getting it back.” He said this just 24 hours after we had wired him the money. Ouch!

That happened more than six years ago but it was something I’ll never forget. A quick Google search today reveals that guy is still alive and kicking as he was recently interviewed about his success in amassing a restaurant empire in Florida.

Over the next couple years, I would hear variations of that “I stole your money” line from other businesses, typically on deals larger than $75,000. These were strategic defaults designed to strong-arm the funding company into a settlement or an attempt to simply walk off with the funds altogether. In other words, fraud.

All this does is raise the cost for the next business that conducts themselves honestly. It’s a damn shame.

Merchants prey on Wall Street

Critics can say what they want about the sophistication of businesses that enter into merchant cash advance transactions. Running a business requires a great deal of intelligence. And to some savvy businessmen, Wall Street’s money is on the menu as fresh meat.

Critics can say what they want about the sophistication of businesses that enter into merchant cash advance transactions. Running a business requires a great deal of intelligence. And to some savvy businessmen, Wall Street’s money is on the menu as fresh meat.

One experience I had was with the owner of a steakhouse in NYC that flew up from his residence in Brazil to try and close me (as the underwriter) on purchasing roughly $400,000 of his future credit card sales. What he didn’t know is that the night before I checked out the place anonymously by having dinner there with my wife. When the bill came, the server told me they no longer accepted credit cards. The next morning, the owner who spoke only in Portuguese arrived in tow with a translator and a lawyer. They traveled directly from JFK to our office, to which I informed them of the decline. They had stopped accepting credit cards a day too early for their scam on us to work and the restaurant closed two months later.

In another case, a souvenir shop in NYC asked if I would come by to pick up his application and statements in person since we were locally-based. After spending a half hour with the guy at his shop, I returned back to the office only to find out that he gave me doctored bank statements.

And then there’s the owner of a florist that made a career off of robbing merchant cash advance companies. The store, which is close to my hometown, had obtained more than 20 merchant cash advances by late 2008 and defaulted on all of them, netting the business close to $1 million. They hoped to make me victim number 21 but we figured it out in the 11th hour before the funds went out. The business is still there today though I’m unsure if it’s still the same owner.

In 2015, fake documentation is an epidemic. Underwriters in the industry cannot rely on faxed or emailed statements alone. They should be verified through APIs or through direct contact with banks. Many funding providers go a step further and actually request the usernames and passwords to business bank accounts just to be absolutely sure that what they’re seeing is what they’re getting.

But as tech-savvy millenials become the face of American small business, the ante is being upped on fraud. One underwriter told me they saw something even more worrisome, a fake bank website.

The scam is this: Knowing the underwriter is going to request the username and password of the business bank account to verify the statements, the applicant has designed a functional replica of a bank website on a web domain they own, one that looks like the bank name. The unsuspecting underwriter logs in to it and verifies the account data. There’s only one problem, it’s all fake.

While this appears to be an isolated event, it just goes to show that the war on bad paper is entering another phase.

Bad paper

While fraud is a substantial cause of the bad paper in the merchant cash advance and business lending industries, hardship does have its place. It is perhaps fortunate that in the commercial space, the paper isn’t sold off into some convoluted world of debt collection. More than likely the business will be dealing with the actual funding provider the entire way through the collections process, not a debt buyer ten levels down the chain. That’s good and bad for them.

It’s good because the owner will able to discuss matters related to the default with the party directly familiar with the original contract.

It’s bad because any chance that the contract and proof of the agreement will somehow get lost in the shuffle is pretty much nil.

Jake Halpern discovered that debtors can win lawsuits by simply challenging the debt buyer to produce evidence the debt is owed. That might work in the consumer world where debt changes hands ten times. On the commercial side, bad paper is an enduring companion. It may be business-to-business but somehow it’s more personal.

Contrast that with the Lending Club nurse who I know only as Member XXXXXXX. His/her debt is in the wind. I have no idea who they are, nor anything about the 277 other people that invested with me.

Halpern spent 256 pages tracing the path of a debt, the companies that bought it, sold it, stole it, and sued for it. It’s amazing how complex it is.

If he were to do a book on bad paper in merchant cash advance, it would go like this:

The business defaulted, the funding provider tried to collect and then sued. The End.

Last modified: February 8, 2015Sean Murray is the President and Chief Editor of deBanked and the founder of the Broker Fair Conference. Connect with me on LinkedIn or follow me on twitter. You can view all future deBanked events here.