Banking

Becoming a Bank – Varo Articulates the Leap from Fintech to Banking

July 26, 2017

Varo Money wants to become Varo Bank. The completely mobile-app driven fintech startup already lets customers juggle financial tasks with the touch of a button but now they want to make it official.

Varo has applied for a full national bank charter with the bank’s headquarters in Utah in hopes of becoming a national bank. Varo is the second fintech startup to apply for a bank charter in as many months, with the SoFi application still pending, though there are key differences to the design of each application.

Colin Walsh, co-founder and CEO of Varo Money, took some time to discuss the bank charter application with deBanked, offering his take on how the future of banking is moving toward mobile and reviving the banker relationship, which has gotten lost along the way.

deBanked: Why a bank charter and why now?

Walsh: We founded Varo with a specific vision: to be an indispensable financial guide for customers, with a full suite of banking and financial products. Our founding intention was to create a bank that made it easier and more affordable to manage money. We’ve been in conversations with the regulators for a number of months, and we completed the “pre-application” process. In the past year the regulators’ openness to new de-novo bank charter applications has shifted.

deBanked: Was SoFi’s recent move to similarly apply for a bank charter any inspiration for you?

Walsh: SoFi’s filing did not affect our process; we’ve been in conversations with regulators for months (see above answer). In addition, SoFi applied for a different type of charter than we did. They applied for a state-chartered ILC, which tend to be used by subsidiaries of companies whose primary business is not banking. We applied for a national bank charter to become a full-service national bank.

deBanked: Have you faced any backlash since applying for the bank charter?

Walsh: Not so far. Varo was founded to make it easier and more affordable for customers to manage their money and improve people’s financial lives. We believe that integrating traditional bank products with modern technology (predictive analytics, contextual alerts/notifications, auto-savings, visualizations) is the best way to achieve this outcome. While it brings a new breed of competition, we believe it is the future of banking and is ultimately in the best interest of consumers.

deBanked: Is Varo 100% smartphone banking? For iOS and Android? What type of growth are you experiencing?

Walsh: We also offer service through Interactive Voice Response and phone. We pushed our iOS app into the Apple App store [in] mid-June and are already experiencing very strong demand.

deBanked: Does Varo issue loans and are they from your balance sheet?

Walsh: Yes and yes. Varo makes unsecured loans to customers in states where we have lending licenses.

deBanked: You come from traditional banking, correct? What do you think of this shift toward online and now mobile banking/lending? Are traditional banks going to be left behind?

Walsh: That is correct, I spent 25 years with traditional banking and financial services companies. 92% of all adults ages 18-36 own a smartphone, and modern technology opens up the possibility of a personal banker in your pocket. The game is changing. Banking used to be a relationship business — but most banks have gotten too big to help the bulk of their customers solve everyday problems and get ahead.

Many incumbent banks aren’t able to make the technological changes that customers of the future will demand. Instead of making step-changes to their technologies, they continue to iterate on the same products and channels that serve the same customers in silos, without imagining what the future of banking could look like.

Varo will be the first entrant to truly challenge the existing banking model. Varo combines proprietary technology and integrated financial solutions to bring relationships back to banking for everyone, all on your phone. Varo is a bank designed around solving financial problems, not pushing products. There’s room for everyone, it’s a very big market, but Varo aims to raise the bar for what consumers should expect from their banks.

deBanked: Do you work with any bank partners?

Walsh: Yes, we have great partnerships with The Bancorp Bank, who serves as our sponsor bank for Varo Money’s current business, and Silicon Valley Bank, where we have our main bank account and a venture debt facility.

deBanked: Are consumers ready to make the shift to 100% mobile banking?

Walsh: We’ve seen that many customers are willing and ready to make the shift. Varo’s vision is that everyone deserves a personal banker in their pocket. Access to financial guidance should be instant when a customer needs it and not bother them when they don’t. We want to reduce stress through financial empowerment so that our customers can fulfill their ambitions, stop worrying and go live their lives.

Just like Amazon disrupted retail by providing instant shopping in a customer’s hand, banking in the future (and even today) doesn’t have to be about geographic coverage anymore. We believe that the future of banking is about providing an on-demand solution that gets customers from A → B with minimal friction and maximum delight. Once customers experience how easy and affordable Varo is, traditional banks seem outdated. Trust, safety, and security are requirements for our business that we take very seriously.

SmartBiz Loans Expands Its Footprint With a NorCal Bank

April 25, 2017Technology-based lending platform SmartBiz Loans, which is dedicated to facilitating SBA loans, has expanded its bank roster. SmartBiz announced today a new partnership with Sacramento-based Five Star Bank, bringing the tally of the number of banks on the startup’s platform to five and thrusting marketplace lending into the spotlight once again.

Five Star already delivers SBA loans to customers but through the SmartBiz platform will slash both the time and costs in the underwriting process while reaching new small business customers in the process.

Evan Singer, CEO of SmartBiz Loans, told deBanked that the mindset of the executive team at the Silicon Valley startup has always been to bring banks back into the fold and to incentivize them to fill a void in the market left by the financial crisis by originating smaller loans, in particular SBA loans.

“What we’ve seen in the market is that good businesses cannot get access to low-priced capital if they want to borrow $250,000. So sure, if they want to borrow $5 million they can get access. That’s why we came up with the idea to bring the banks back through fintech,” he said.

Five Star Bank, a privately held bank with $850 million in total assets, is pleased to be among those ranks. James Beckwith, president and CEO of Five Star Bank, was introduced to the SmartBiz technology about a year ago after which time the bank execs began the due diligence process.

“I was intrigued,” Beckwith told deBanked. “We felt the need to somehow play in the space. But we also knew it wasn’t practical for us to develop our own platform. So this was really right in our sweet spot of how we like to partner with people.”

As a result of the partnership Five Star Bank, which makes loans from its own balance sheet, is reaching small business clients the bank did not have access to before.

“Our market presence didn’t allow us to touch a lot of these businesses before, whether from Los Angeles, or Arizona, or San Jose. It’s really people we were unable to touch now being touched through the SmartBiz partnership,” said Beckwith, adding that the small businesses span industry verticals.

“At this point we’re looking at deals in the Western United States and we hope to expand that. The small businesses are really all types – construction companies, PR firms, consulting firms, — there’s no concentration in terms of industry type,” he noted.

The bank’s target customer is seeking a loan for $350,000 or less and the average loan size is $250,000 to $270,000. Terms of an SBA loan on this platform are comprised of a rate of Prime plus 2.75 over a 10-year period.

“The term is much longer and the rate is much lower than traditional loans. Small businesses can save thousands of dollars per month by getting an SBA loan through the SmartBiz and Five Star partnership,” said Singer. In fact, Five Star bank spends about one-tenth of the time on a file or customer originating from SmartBiz than it would on a customer coming from the traditional retail side of their business.

Industry Shakeout

Much of the fallout in the marketplace lending market segment has been tied to the stigma of subprime lending. Beckwith is quick to point out, however, that the underwriting standards for the loans on this platform, which are agreed upon by both Five Star and SmartBiz, are high.

“If you look at some of the average FICO scores we are doing, they are actually good deals. They’re SBA, they’re not subprime deals. I would not characterize them as subprime deals at all,” Beckwith said.

Meanwhile the marketplace lending segment has undoubtedly become more crowded in recent years, attracting the likes of lenders and non-lenders alike, evidenced by the participation of Amazon and Square Capital in this space, for instance.

According to Singer some industry shakeout can be expected in the near term. He expects over the next couple of years that those marketplace lenders and other alternative lenders unable to meet customer demands will either experience a wave of consolidation or they simply won’t be around any longer.

“We are already starting to see a number of our loan proceeds being used to refinance expensive shorter-term debt where they save thousands per month. Businesses are getting smarter with available options and folks that are able to best meet and deliver with small businesses on their minds first are going to come out on top,” said Singer.

SBA 7(a) Cap

As a technology platform dedicated to SBA loans, the issue of the program’s annual allotted cap is something that gets revisited on an ongoing basis. Nonetheless even when the SBA program has come close to suspension, Congress has stepped in to keep it afloat.

“The great thing about SBA is that it has support from both sides of the aisle in D.C. We’ll see what happens this year,” said Singer.

James agrees. “Every year that this becomes an issue the cap has been increased. I feel comfortable that what has happened in the past will happen again in the future because these programs are very viable. The small business space has very strong economic development activity.”

If they’re right this bodes well not only for the Smart Biz and Five Star partnership but also the new banks that the tech-based lender has in its pipeline.

“We are adding banks into the marketplace. And we’re selective about who we add,” Singer said.

Dear Fintech, The OCC Wants to Welcome You to The Family

March 16, 2017 Congratulations fintech, you did it. The OCC wants fintech companies who are interested and meet the criteria, to apply for a Special Purpose National Bank (SPNB) charter if they so choose, according to a licensing manual published by the agency.

Congratulations fintech, you did it. The OCC wants fintech companies who are interested and meet the criteria, to apply for a Special Purpose National Bank (SPNB) charter if they so choose, according to a licensing manual published by the agency.

“Providing a path for fintech companies to become national banks can make the financial system stronger by promoting growth, modernization, and competition,” is one of several arguments they make in their decision to move forward. And it would be optional, something a company could choose to pursue.

“The OCC will expect an SPNB applicant whose business plan includes lending or providing financial services to consumers or small businesses to demonstrate a commitment to financial inclusion,” they say and that commitment must be documented in an official plan which must be put up and submitted for public comment. Basically, the entire process will be very public so it’s unlikely that companies will slip through and become banks without anyone really knowing.

New York’s Department of Financial Services nonetheless issued a heated response to the proposal. “The imposition of an entirely new federal regulatory scheme on an already fully functional and deeply rooted state regulatory landscape will invite efforts to evade state usury laws and other consumer protections, stifle small business innovation, create institutions that are too big to fail, and increase the risks presented by nonbank entities,” they wrote. They see the move as an attack on their in-state regulatory powers. “The proposal threatens to create an entirely new federal regulatory program, creating serious regulatory uncertainty that threatens to invade state authority and sovereignty.”

Read the OCC’s charter licensing manual here

Read the NYDFS response here

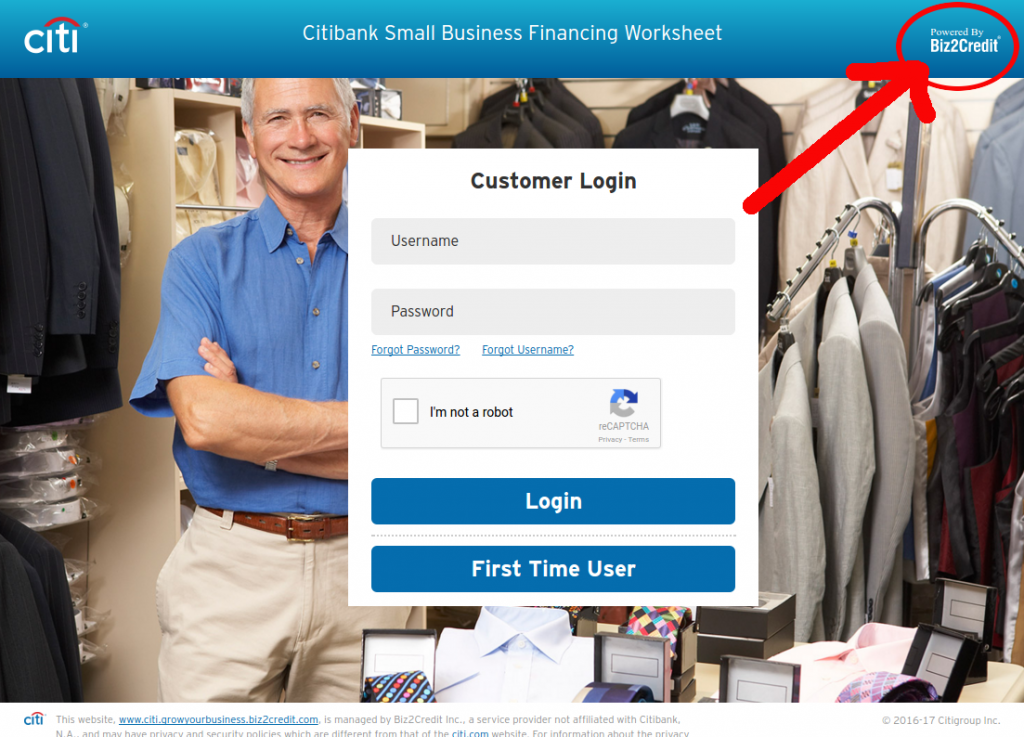

Biz2Credit – Citigroup Small Business Loan Partnership Spotted

January 27, 2017Business Insider revealed that Biz2credit and Citigroup have quietly partnered up on a website to make small business loans up to $1 million. There was no actual link to it, so we’ve found it ourselves.

The link appears in several areas of Citi’s website under the small business finance category and that brings you here:

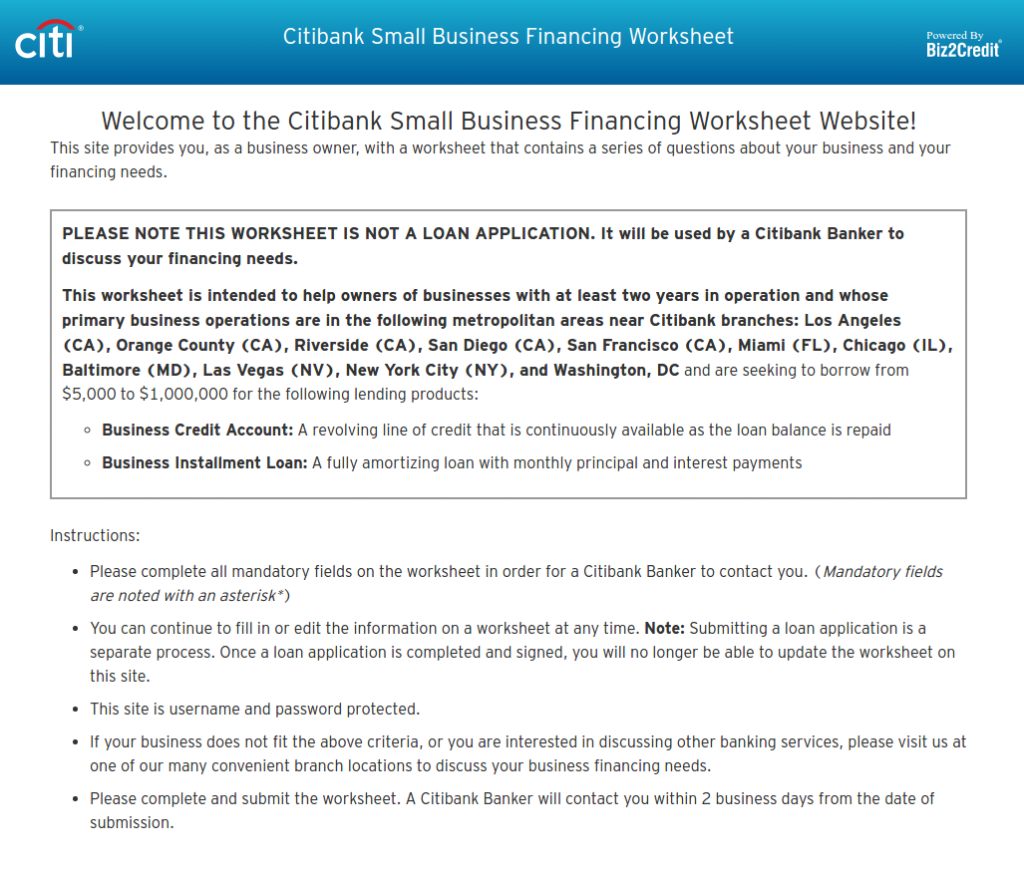

When you go to register, a page pops up insisting that this isn’t a loan application, but rather just a “worksheet” to have a banker from Citi call you within 2 days. “It will be used by a Citibank Banker to discuss your financing needs,” it reads.

The worksheet asks for very basic information such as name, business name, address, annual revenue, and financing requested.

If this doesn’t sound overly advanced, perhaps that’s why it’s being kept on the down low. According to Business Insider, Biz2credit CEO Rohit Arora said they have chosen not to publicize the effort because it’s in the very early stages.

The cat’s out of the bag now…

Two U.S. Senators Say ‘Not So Fast’ to OCC’s Plans for Limited Charter

January 10, 2017

Senator Sherrod Brown (D) and Jeffrey A. Merkley (D) both believe that the OCC does not possess the authority to grant the limited purpose charters it plans to move forward with. In a letter penned to Comptroller Thomas Curry on Monday, Brown and Merkley raise several concerns including that such charters would only blur the lines between banking and commerce, pointing out that an applicant need not necessarily be a fintech company to apply, nor need or want to accept deposits.

“As state banking supervisors have pointed out, because so many companies under an alternative charter would be exempt from the Bank Company Holding Act, nothing would ensure that both bank and currently impermissible non-bank activities were intermingled in one company, and that a commercial entity could not create or acquire an alternatively chartered company,” they write.

Brown and Merkley’s other concerns may be premature since the OCC is currently seeking information from the fintech industry on such issues in its official 13-question Request for Comment (found on the last pages of this document).

The full letter submitted to Comptroller Curry can be viewed here.

The OCC Wants Online Lenders to Become Limited Purpose Banks

December 2, 2016 Earlier today, Comptroller of the Currency Thomas J. Curry announced that the OCC will move forward with chartering financial technology companies that offer bank products and services that meet their high standards and chartering requirements.

Earlier today, Comptroller of the Currency Thomas J. Curry announced that the OCC will move forward with chartering financial technology companies that offer bank products and services that meet their high standards and chartering requirements.

“We have decided to move forward and to make available special purpose national charters to fintech companies for a few basic reasons,” he began saying during a speech at the Georgetown University Law Center. “First and foremost, we believe doing so is in the public interest. Fintech companies hold great potential to expand financial inclusion, empower consumers, and help families and businesses take more control of their financial matters.”

Curry also responded to critics who argued that a limited charter would put fully regulated banks at a disadvantage competitively. “The reality today is that the 4,000 fintech companies out there are already competing with national and state banks, without regard to any of the national bank responsibilities and under a patchwork of supervision,” he said. “Granting national charters to the companies who desire and warrant one doesn’t weaken the competitive position of existing banks or the dual banking system. In some ways, it levels the playing field because statutes that by their terms apply to national banks would apply to all special purpose national banks, even uninsured ones.”

Applying for this charter would be optional, not a requirement.

Like the Treasury RFI last year, the OCC has put up an official 13-question Request For Comment that is open until January 15th.

Those questions are:

1. What are the public policy benefits of approving fintech companies to operate under a national bank charter? What are the risks?

2. What elements should the OCC consider in establishing the capital and liquidity requirements for an uninsured special purpose national bank that limits the type of assets it holds?

3. What information should a special purpose national bank provide to the OCC to demonstrate its commitment to financial inclusion to individuals, businesses and communities? For instance, what new or alternative means (e.g., products, services) might a special purpose national bank establish in furtherance of its support for financial inclusion? How could an uninsured special purpose bank that uses innovative methods to develop or deliver financial products or services in a virtual or physical community demonstrate its commitment to financial inclusion?

4. Should the OCC seek a financial inclusion commitment from an uninsured special purpose national bank that would not engage in lending, and if so, how could such a bank demonstrate a commitment to financial inclusion?

5. How could a special purpose national bank that is not engaged in providing banking services to the public support financial inclusion?

6. Should the OCC use its chartering authority as an opportunity to address the gaps in protections afforded individuals versus small business borrowers, and if so, how?

7. What are potential challenges in executing or adapting a fintech business model to meet regulatory expectations, and what specific conditions governing the activities of special purpose national banks should the OCC consider?

8. What actions should the OCC take to ensure special purpose national banks operate in a safe and sound manner and in the public interest?

9. Would a fintech special purpose national bank have any competitive advantages over full service banks the OCC should address? Are there risks to full-service banks from fintech companies that do not have bank charters?

10. Are there particular products or services offered by fintech companies, such as digital currencies, that may require different approaches to supervision to mitigate risk for both the institution and the broader financial system?

11. How can the OCC enhance its coordination and communication with other regulators that have jurisdiction over a proposed special purpose national bank, its parent company, or its activities?

12. Certain risks may be increased in a special purpose national bank because of its concentration in a limited number of business activities. How can the OCC ensure that a special purpose national bank sufficiently mitigates these risks?

13. What additional information, materials, and technical assistance from the OCC would a

prospective fintech applicant find useful in the application process?

Read the OCC’s 17 page report on the matter. The Request For Comment and submission instructions are at the end of it.

UK’s P2P Pioneer Wants to Be a Bank. Who’s Next?

November 16, 2016

UK’s P2P pioneer Zopa is changing its stripes to turn into a bank.

The 11-year-old company, upbeat about the regulatory environment in the UK that is looking to bring innovation and entrepreneurship to banking, will apply for a license soon. “Zopa has a history of creating innovative retail-facing financial services, driving consumer choice and transparency. We are responding to the positive regulatory environment and building on our experience to bring yet more choice to the market,” said CEO Jaidev Janardhan in a press release.

The new Zopa Bank will be a retail bank and provide deposit and savings accounts, thereby giving the company a stable funding source for its P2P platform.

This trend has also picked up pace across the pond, at home. For online lenders like SoFi that are adding lending products faster than they can secure sources of capital, the prospect of becoming a bank may now be more tempting than disrupting them. Marketplace lending companies in the US including Avant, Prosper and Lending Club are struggling to retain and grow investors on their platforms.

While tightening credit and raising rates to prevent delinquencies is one way to keep investors, some companies like SoFi have also started hedge funds to buy up their own loans. The advent of online lending promised to offer alternatives to the already chunky, fragmented banking system which was further straitjacketed by regulation like the Dodd-Frank Act which mandated banks have stricter lending standards. However, the rapid proliferation of the industry has brought forth concerns like fast depleting capital and waning investor interest.

Will alternative lenders in the US also drink the kool-aid and become the entity they intended to overhaul?

Debanked: Europe’s ING Bank, Commerzbank to Slash Jobs, Go Digital

October 3, 2016Europe is debanking.

Last week, two large European banks — ING and Commerzbank announced they are slashing jobs and spending the savings on digitizing its their businesses.

Amsterdam-based ING Bank will slash 7,000 jobs, around 3500 jobs in Belgium and another 2300 in the Netherlands. The savings ( around 900 million euros in five years) under the bank’s ‘Think Forward’ strategy, will be used to migrate to a single integrated banking platform in the Netherlands and Belgium. Separately, ING will also invest 800 million euros in digital initiatives over the next five years.

“Customers are increasingly digital and bank with us more and more through mobile devices. Their needs and expectations are the same, all over the world, and they expect us to adopt new technology as fast as companies in other sectors,” said CEO Ralph Hammers in a statement.

ING is not alone in marching towards technology; Germany-based Commerzbank also said that it will slash approximately 7,300 jobs over the next four years and spend 700 million euros annually on technology under its ‘Commerzbank 4.0’ strategy. Later this month, the bank plans to roll out ‘One,’ an integrated sales interface, enabling the bank’s sales staff and customers to interact and transact on the same platform and by 2020, it aims to have 80 percent of its relevant business processes digitized.

“It is inevitable that the various measures and intentions announced today may have a significant impact on many of our colleagues. It means some functions will change significantly in nature,” said Hammers.

The move from major banks is coming at a time when fintech is heating up — Europeans startups raised $348 million (£238.2 million) in the first quarter of the year, up from $337 million (£230.6 million) in the first three months of 2015. And with banks deciding to go lean, it could only open up the opportunity for more collaboration than competition among banks and startups.