Open Banking — A U.S. Pipe Dream or Near-Term Reality?

Some alternative funders are anxious for “open banking” to become the gold standard in the U.S., but achieving widespread implementation is a weighty proposition.

Some alternative funders are anxious for “open banking” to become the gold standard in the U.S., but achieving widespread implementation is a weighty proposition.

Open banking refers to the use of open APIs (application program interfaces) that enable third-party developers to build applications and services around a financial institution. It’s a movement that’s been gaining ground globally in recent years. Regulations in the U.K., a forerunner in open banking, went into effect in January, while several other countries including Australia and Canada are at varying stages of implementation or exploration.

For the U.S., however, the time frame for comprehensive adoption of open banking is murkier. Industry participants say the prospects are good, but the sheer number of banks and the fragmented regulatory regime makes wholesale implementation immensely more complicated. Nonetheless, industry watchers see promise in the budding grass-roots initiative among banks and technology companies to develop data-sharing solutions. Regulators, too, have started to weigh in on the topic, showing a willingness to further explore how open banking could be applied in U.S. markets.

Open banking “is a global phenomenon that has great traction,” says Richard Prior, who leads open banking policy at Kabbage, an alternative lender that has been active in encouraging the industry to develop open banking standards in the U.S. “It’s incumbent upon the U.S. to be a driver of this trend,” he says.

The stakes are particularly high for alternative lenders since they rely so heavily on data to make informed underwriting decisions. Open banking has the potential to open up scores of customer data and significantly improve the underwriting process, according to industry participants.

“Open banking massively enables alternative lending,” says Mark Atherton, group vice president for Oracle’s financial services global business unit. What’s missing at the moment is the regulatory stick to ensure uniformity. Certainly, data sharing is gradually becoming more commonplace in the U.S. as banks and fintech companies increasingly explore ways to collaborate. But even so, banks in the U.S. are currently all over the map when it comes to their approach to open banking, posing a challenge for many alternative lenders. Many alternative lenders would like to see regulators step in with prescriptive requirements so that open banking becomes an obligation for all banks, as opposed to these decisions being made on a bank-by-bank basis. Especially since many consumers want to be able to more readily share their financial information, they say.

“It will create huge value to everyone if that data is more accessible,” says Eden Amirav, co-founder and chief executive of Lending Express, an AI-powered marketplace for business loans.

Some global-minded banks like Citibank have been on the forefront of open banking initiatives. Spanish banking giant BBVA is also taking a proactive approach. In October, the bank went live in the U.S. with its Banking-as-a-Service platform, after a multi-month beta period. Also in October, JPMorgan Chase announced a data sharing agreement with financial technology company Plaid that will allow customers to more easily push banking data to outside financial apps like Robinhood, Venmo and Acorns.

There are several other examples of open banking in action. Kabbage customers, for instance, authorize read-only access to their banking information to expedite the lending process through the company’s aggregator partners, says Sam Taussig, head of global policy at Kabbage.

Also, companies such as Xero and Mint routinely interface with banks to put customers in control of their financial planning. And companies like Plaid and Yodlee connect lenders and banks to help with processes such as asset and income verification.

Some banks, however, are more reticent than others when it comes to data sharing. And with no regulatory requirements in place, it’s up to individual banks how to proceed. This can be nettlesome for alternative lenders trying to get access to data, since there’s no guarantee they will be able to access the breadth of customer data that’s available. “As an underwriter, you want the whole financial picture, and if data points are missing, it’s hard to make appropriate lending decisions,” Taussig says.

The problem can be particularly acute among smaller banks, industry participants say. While the quality of data you can get from one of the money-center banks is quite good, “as you go down the line, it becomes a little less consistent,” says James Mendelsohn, chief operating officer of Breakout Capital Finance. For these smaller banks, the issue is sometimes one of control. There’s a feeling among some community banks, that “if I make it easier for my small business customers to get loans elsewhere, I’m done,” says Atherton of Oracle.

Absent regulatory requirements, alternative lenders are hoping that this initial hesitation among some banks changes over time as they continue to gain a better understanding of the market opportunity and as more of their counterparts become open to data sharing through APIs.

Open banking could be a boon for banks in that it would enable them to service customers they probably couldn’t before, says Jeffrey Bumbales, marketing director at Credibly, which helps small and mid-size businesses obtain financing. Open banking makes for a “better customer experience,” he says.

One challenge for the U.S. market is the hodgepodge of federal and state regulators that makes reaching a consensus a more arduous task. It’s not as simple here as it may be in other markets that are less fragmented, observers say.

Major rule-making would be involved, and there are many issues that would need attention. One pressing area of regulatory uncertainty today is who bears the liability in the event of a breach—the bank or the fintech, says Steve Boms, executive director of the Northern American chapter of the Financial Data and Technology Association. Existing regulations simply don’t speak to data connectivity issues, he says.

To be sure, policymakers have started to give these matters more serious attention, with various regulators weighing in, though no regulator has issued definitive requirements. Still, some industry participants are encouraged to see regulators and policymakers taking more of an interest in open banking.

A recent Treasury Report, for example, notes that as open banking matures in the United Kingdom, “U.S. financial regulators should observe developments and learn from the British experience.” And, The Senate Banking Committee recently touched on the issue at a Sept. 18 hearing. Industry watchers say these developments are a step in the right direction, though there’s significant work needed, they say, in order to make open banking a pervasive reality.

“We’re seeing the pace and interest around these things picking up pretty significantly,” Boms says. Even so, it can take several years to implement a formal process. “The hope is obviously as soon as possible, but the financial services sector is a very fragmented market in terms of regulation. There’s going to have to be a lot of coordination,” Boms says.

Another challenge to overcome is customers’ willingness to use open banking. Many small business owners are more comfortable sending a PDF bank statement versus granting complete access to their online banking credentials, says Mendelsohn of Breakout Capital Finance. “There’s a lot more comfort on the consumer side than there is on the small business side. Some of that is just time,” he adds.

Certainly sharing financial data is a concern—even in the U.K. where open banking efforts are well underway. More than three quarters of U.K. respondents expressed concern about sharing financial data with organizations other than their bank, according to a recent poll by market research body, YouGov. This suggests that more needs to be done to ease consumers into an open banking ecosystem.

The topic of data security came up repeatedly at this year’s Money20/20 USA conference in Las Vegas. How to make people feel comfortable that their data is safe is a pressing concern, says Tim Donovan, a spokesman for Fundbox, which provides revolving lines of credit for small businesses. Clearly, it’s something the industry will have to address before open banking can really become a reality in the U.S., he says.

Despite these challenges, many market watchers feel open banking in the U.S. is inevitable, given the momentum that’s driving adoption worldwide. Several countries have taken on open banking initiatives and are at varying states of implementation—some driven by industry, others by regulation. Here is a sampling of what’s happening in other regions of the world:

In the U.K., for example, the implementation process is ongoing and is expected to continually enhance and add functionality through September 2019, according to The Open Banking Implementation Entity, the designated entity for creating standards and overseeing the U.K’s open banking initiative.

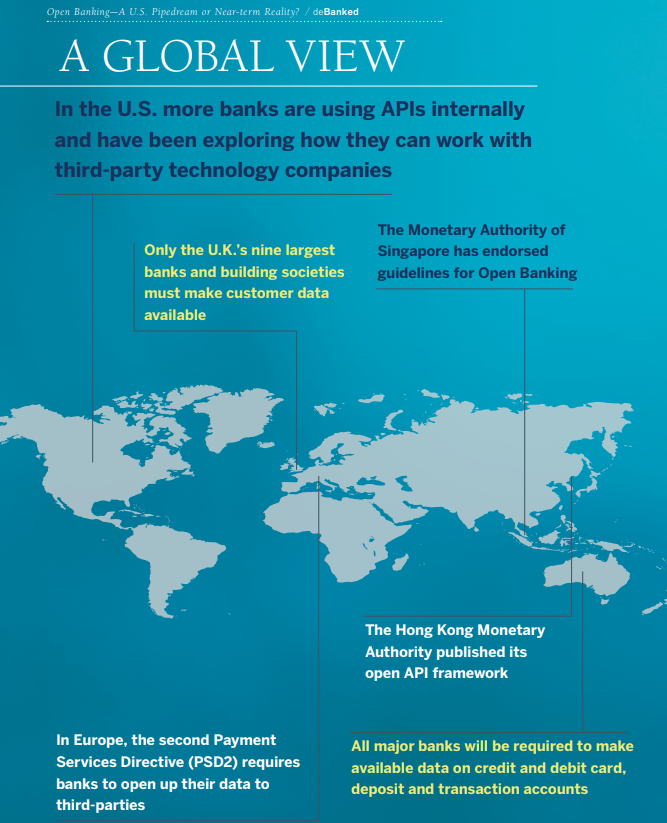

At the moment, only the U.K.’s nine largest banks and building societies must make customer data available through open banking though other institutions have and continue to opt in to take part in open banking. As of September, there were 77 regulated providers, consisting of third parties and account providers and six of those providers were live with customers, according to the U.K. open banking entity.

In Europe, the second Payment Services Directive (PSD2) requires banks to open up their data to third parties. But implementation is taking longer than expected—given the large number of banks involved. By some opinions, open banking won’t really be in force in Europe until September 2019, when the Regulatory Technical Standards for open and secure electronic payments under the PSD2 are supposed to be in place.

In Australia, meanwhile, the country has adopted a phase-in process to take place over a period of several years through 2021. Starting in July 2019, all major banks will be required to make available data on credit and debit card, deposit and transaction accounts. Data requirements for mortgage accounts at major banks will follow by February 1, 2020. Then, by July 1 of 2020, all major banks will need to make available data on all applicable products; the remaining banks will have another 12 months to make all the applicable data available.

For its part, Hong Kong is also pushing ahead with plans for open banking. In July, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority published its open API framework for the local banking sector. There’s a multi-prong implementation strategy with the final phase expected to be complete by mid-2019.

Singapore, by contrast, is taking a different approach than some other countries by not enforcing rules for banks to open access to data. The Monetary Authority of Singapore has endorsed guidelines for Open Banking, but has expressed its preference to pursue an industry-driven approach as opposed to regulatory mandates.

Other countries, meanwhile, are more in the exploratory phases. In Canada, the government announced in September a new advisory committee for Open Banking, a first step in a review of its potential merits. And in Mexico, the county’s new Fintech Law requires providers to provide fair access to data, and regulators there are reportedly gung-ho to get appropriate regulations into place. Still other countries are also exploring how to bring open banking to their markets.

The U.S. meanwhile, is on a slower course—at least for now. More banks are using APIs internally and have been exploring how they can work with third-party technology companies. Meanwhile, companies like IBM have been coming to market with solutions to help banks open up their legacy systems and tap into APIs. Other industry players are also actively pursuing ways to bring open banking to the market.

As for when and if open banking will become pervasive in the U.S., it’s anyone’s guess, but industry participants have high hopes that it’s an achievable target in the not-too-distant future.

Thus far, there has been little pressure for banks to adopt open banking policies, says Taussig of Kabbage. But this is changing, and things will continue to evolve as other countries adopt open banking and as pressure builds from small businesses and consumers in an effort to ensure the U.S. market stays competitive, he says. Open banking “is going to happen in the near future,” Taussig predicts.

Last modified: December 19, 2018