Why We Shouldn’t Stop Calling it Peer-to-Peer Lending

There’s a troubling undercurrent brewing in the marketplace industry, the death of the word peers. We’re not supposed to say peer-to-peer lending anymore since few platforms actually allow for people to lend directly to their peers. In the case of Lending Club and Prosper, investors are actually lending money to the platforms themselves.

There’s a troubling undercurrent brewing in the marketplace industry, the death of the word peers. We’re not supposed to say peer-to-peer lending anymore since few platforms actually allow for people to lend directly to their peers. In the case of Lending Club and Prosper, investors are actually lending money to the platforms themselves.

Emphasizing the appropriate terminology probably makes it easier for people to understand. If it’s not peer-to-peer after all, then calling it that only serves to mislead potential borrowers and investors alike. And yet the term persists largely because the average person is still able to invest in an asset class it never was able to before, notes backed by the performance of individual consumer loans.

It could be argued that without money from peers to buy these notes, the loans themselves would never get issued, making it still peer-dependent or at least peer-relevant.

A game for Wall Street

Jorge Newberry wrote several months ago that the little guy as most of us imagine a peer to be, is dead. He was replaced by Wall Street, BlackRock, and Wealthy bankers. “These were killers,” He wrote. He added that while the industry “initially attracted ordinary citizens to invest in modestly sized consumer loans to people like them, over the last few years those peer investors often have been elbowed out and replaced by Wall Street’s finest.”

Retail investors have bemoaned the trend via online message boards, sometimes even accusing the platforms of giving the institutions first dibs on the highest quality loans and leaving the little guys to fight over nothing but the scraps that are more likely to underperform.

Even Dara Albright, the co-founder of the LendIt conference has acknowledged the takeover. In The Financial Advisor’s Guide to P2P Investing, Albright writes, “Unfortunately, what began as a true person-to-person marketplace – with the ordinary individuals lending to and borrowing from one another – has since become monopolized by institutional investors whose deep pockets and technological advantages have all but driven the individual lenders out.”

Further along in the paper, Albright makes the case that individuals need to take advantage of the yield these loans offer to narrow the wealth divide. She makes a compelling argument for investing but stops short of proposing a solution to regain market share. “There aren’t enough p2p loans to facilitate the strong investment appetite,” she concluded.

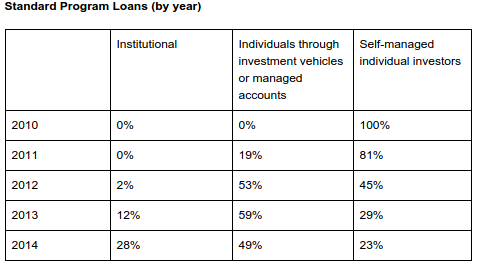

But just as the marketplace community has conceded the death of peers, the numbers don’t exactly reflect their sentiment.

Only 28% of Lending Club’s loans went to institutional investors in 2014.

Only 28% of Lending Club’s loans went to institutional investors in 2014.While Newberry and Albright have made the case that retail investors are being locked out, there’s a dangerous flip side, they just might be getting locked in. If marketplace lending truly is becoming a game for Wall Street by Wall Street, then the few retail investors who are invested in it could eventually become collateral damage in a pissing match between wealthy bankers.

Investor faith

There are already concerns that the incentive for marketplaces are not aligned with those of their investors. PeerCube co-founder Anil Gupta wrote this on the LendAcademy forum about Prosper, “The quest to increase originations and revenue will trump any such risk management attempts, like what happened with banks issuing mortgages to unqualified borrowers in order to boost their own bottom lines.” He wrote that in response to an upset user whose borrower declared bankruptcy before making even a single payment towards their Prosper loan.

The user was questioning how Prosper would handle this since the timing of the loan prior to the bankruptcy filing had all the hallmarks of fraud.

Gupta added, “There is very little incentive for LC and Prosper to pursue such collections and recoveries claims. When LC was investing its own money in loans, they pursued collections and recoveries more vigorously (11.19% collection in 2007 vs 5.53% collection in 2011). It is no longer Prosper and LC money at risk.”

The user is not alone in his collections fears. Just a few days earlier I realized that 4.6% of all the notes I had purchased on Lending Club had already defaulted, a number that troubled me considering my average note is only 10 months old. With another 3-4 years still to go until maturity, the rate of defaults is already quite high.

The user is not alone in his collections fears. Just a few days earlier I realized that 4.6% of all the notes I had purchased on Lending Club had already defaulted, a number that troubled me considering my average note is only 10 months old. With another 3-4 years still to go until maturity, the rate of defaults is already quite high.

And while I’ve been told that my own personal stats are relatively normal, other retail investors occasionally run into quirks that force them to question the soundness of the reporting they receive.

For example, veteran users commonly rely on the FICO score updates Lending Club will publish for each issued loan. If a borrower’s score is dropping, you could sell the note for a discount to an interested buyer on a marketplace such as folio. Several people have admitted to using this strategy to mitigate losses. There’s just one problem, a user discovered a discrepancy in Lending Club’s FICO reporting. In at least one case, the borrower’s FICO score may have been overstated by more than a hundred points. For users beholden to the accuracy of these figures in order to properly execute their investment strategy, it’s a difficult pill to swallow.

Call it a kink or an oddity. Maybe it’s something that needs to be fixed or maybe something is being miscommunicated. Whatever is going on there, these are the kinds of risks that institutional capital is supposed to be able to tolerate in their quest for yield, but it’s gut wrenching for retail investors.

In the instance of the suspected bankruptcy fraud, several responses by fellow investors gave the impression that the platform simply isn’t going to care because they make money off of issuing loans, not collecting on them. That’s the exact type of Wall Street attitude that could come back to hurt retail investors.

Marketplace lending might not technically be designed as peer-to-peer but the little guy and their actual peers certainly have their funds at stake. Calling it a game for big banks, the wealthy, and Wall Street only encourages the players involved to take bigger risks, reduce transparency, and shrug off genuine criticism.

We can’t let that happen.

Last modified: June 1, 2015Sean Murray is the President and Chief Editor of deBanked and the founder of the Broker Fair Conference. Connect with me on LinkedIn or follow me on twitter. You can view all future deBanked events here.